Update 12/2: This article has been updated to reflect the impact of the non-tender of Adam Duvall

As a rookie in 2019, Austin Riley posted a .307 wOBA. As a sophomore in 2020, Austin Riley posted a .307 wOBA. So it seems pretty straight forward to assume that in 2021, Austin Riley is going to post something close to a .307 wOBA. Barring some kind of Khris Davis effect, it is highly unlikely he would post exactly .307 again, but who knows!

And yet, early 2021 Steamer projections signal a potential breakout for Atlanta’s young bat. Riley, who will turn 24 just after Opening Day, is projected for a .332 wOBA, effectively taking him from a guy you would prefer not to have in your lineup to a just-above-league-average bat. Steamer isn’t alone, either. The ZiPS three year projections on Riley’s FanGraphs player page show a .337 wOBA in 2021 and .339 in 2022.

These projection systems are seeing something that suggests Riley is going to start to make good on the promise he showed tearing up AA and AAA as a 21- and 22-year-old. Given 503 rather unimpressive MLB plate appearances, the obvious question is, “What do they see?”

Career to Date

Riley’s short career has had three (very short) phases in it, and there are some interesting patterns at play. From his debut on May 15, 2019, through the end of June 2019, Riley was crushing the ball. His .273/.326/.582 line flashed big power. A .309 ISO from a 22-year-old getting his first taste of Major League pitching is something to get excited about. But there were red flags, particularly a 32.6% K-rate. He was chasing way too often (43% O-Swing) and swinging through way too many pitches (20.1% swinging-strike rate). For context, over those six weeks, only nine players chased more pitches outside the zone and only one (Javier Baez) swung through pitches more often.

From July 1 through the end of the 2019 season, the K-rate not only caught up with him but got worse. He got more patient (O-Swing down to 38.8% and overall swing rate dropped from 58.2% to 53.5%) but kept whiffing (21.6% swinging-strike rate). The result was more deep counts, more walks, but also more strikeouts. He also made less authoritative contact, with his average exit velocity dropping from 90.4 to 87.7 and his BABIP dropping to .228. He posted an abysmal .210 wOBA.

It’s worth noting that this stretch was interrupted by an IL stint for a knee injury, which may have impacted performance. But whatever happened these few weeks were ugly.

At first glance, the third segment of his career (2020) split the difference between the first two. After a .371 wOBA in the first six weeks and .210 the rest of the way in 2019, he posted the previously mentioned .307 in 2020.

But even a cursory look shows that his .307 wOBA in 2020 was the same size as his 2019 (also .307) but a very different shape. He struggled to get on base in 2019, but hit for power, with a .279 OBP, a .471 SLG and a .245 ISO. In 2020, he got on base more (a still-not-impressive .301 OBP), but the power dried up (.415 SLG, .176 ISO).

Plate Discipline Gains

In 2019, the big problem for Riley, even when he was performing, was strikeouts. Among players with 200+ PA, his 2019 K% was the fourth-worst in baseball and the three players worse than him were either really, really bad (Keon Broxton, Chris Davis) or have absurd otherworldly power (Joey Gallo). Only Jorge Alfaro and Adalberto Mondesi had higher swinging strike rates.

But 2020 was a different story. His K% dropped from 36.4% to 23.8% while his BB% increased from 5.4% to 7.8%. He went from one of the most strikeout prone hitters in all of baseball to the 45th highest K rate among 124 hitters with 200+ PA in 2020. His BB/K went from 0.15 to 0.33.

He did this by coupling the improved patience from the second half of 2019 (O-Swing of 37.1% in 2020) with much more contact (contact% up from 63.2% to 72.5% and swinging-strike rate down from 20.5% to 14.8%).

Yet those gains didn’t show up in his overall performance. There were 116 players with 200+ PAs in both 2019 and 2020. Riley’s 12.6% gain in K% was the largest of any player (Aaron Hicks was second at an improvement of 10.2%). Fourteen players (including Riley) improved by 5% or more and, on average, they improved their wOBA by .029. The top five K% improvers saw their wOBA go up by .038 on average. Riley had the 19th largest improvement in his BB/K. The top 20 improved their wOBA by .023 on average.

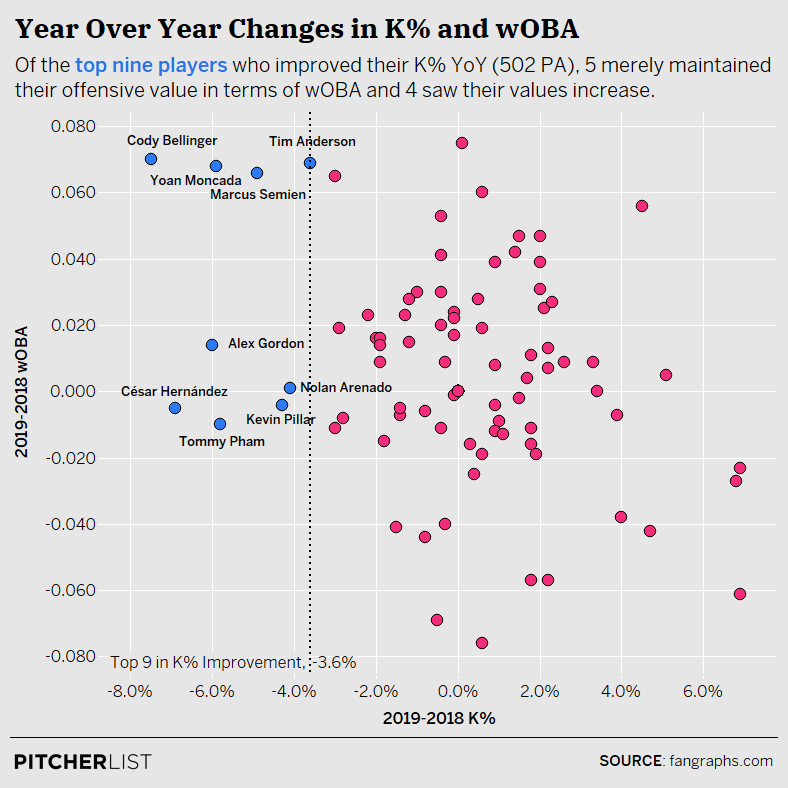

Putting a little more rigor behind this shows the relationship between changes in K% and changes in wOBA using full-season data from 2018 to 2019.

There is definitely a relationship between changes in K% and wOBA. Hitters who improve their K% (on the left side of that graph) usually see an increase in their wOBA. But that doesn’t always happen.

Looking at the graph, there are nine players who saw a greater than 3% decrease in their K%. There are two clear explanations for the improvement.

Six of the nine (Cesar Hernandez, Alex Gordon, Yoán Moncada, Tim Anderson, Kevin Pillar, and Nolan Arenado) were no more selective, but did make more contact. In some cases they chased more than they had previously, but because they made more contact, they also struck out less. The problem is, they all also walked less – they got more aggressive, made more contact, faced fewer deep counts. Those players either fell below the dotted blue line (their wOBA increased less than we would have expected based on K% change) or they rode big increases in BABIP to big improvements in production. This isn’t a surprise – if you make more contact you are going to be more dependent on BABIP. They saw their wOBA increase by .024 on average.

But Riley doesn’t look like these guys, he looks like the second group. The second group (Cody Bellinger, Tommy Pham, and Marcus Semien) were more patient. They may or may not have made more contact, but they were less likely to chase pitches, even if they were more aggressive in the zone. All three not only struck out less but walked more. Pham saw a decrease in BABIP, plus a drop in his contact quality per Statcast which resulted in a drop in his wOBA, but the other two were among the biggest wOBA gainers in baseball. As a trio (including Pham’s poor showing), their wOBAs increased by .042 on average.

Riley’s improvements in K% from 2019-2020 were so large they would be off this graph. And he did it by being more patient, walking more, and swinging at pitches he could hit. But his wOBA was unchanged.

So what gives?

Lost Power

Riley flashed big power in his debut and that wasn’t a huge surprise. This line from Baseball America’s 2019 Riley scouting report is pretty typical:

Riley’s plus-plus raw power has always been his best attribute. He has the potential to hit 25-30 home runs regularly in the majors.

Yet, in 2020, with the new and improved approach at the plate, his power was absent. His ISO dropped from .245 to .176. It’s possible the improved patience hampered his ability to hit with authority, but the evidence for that isn’t strong.

| Stat | 2019 | 2020 | 2020 Percentile |

| Barrel Rate | 13.7% | 10.0% | 64th |

| Hard Hit Rate | 44.5% | 42.9% | 69th |

| Avg EV | 89.4 | 91.0 | 82nd |

While his exit velocity increased, his barrel and hard-hit rates dropped, but all were still comfortably above average. Nothing here is really a cause for concern. If anything, there is more reason for optimism. His 2020 batted ball data is plenty good to support a strong offensive profile and the even-better 2019 numbers are a reminder that he is capable of more.

Here you can see him tee off on his hardest-hit ball of the year (111 exit velocity) and the second hardest of his career.

The biggest concern in his Statcast data is his launch angle, which went from 20.6 to 13.6, leading to a big shift away from fly balls and towards ground balls. Riley hits the ball hard but needs to get back to hitting it in the air. What is the difference between 13.6 and 20.6?

Here is Riley smoking a ball 104.8 MPH at a 13-degree launch angle:

Hit hard, but lands in front of the LF for a single that doesn’t even score the run from second (thanks to an assist from Green Monster-influenced OF positioning).

Here he is, 24 hours later, at 109.3 MPH with a 19-degree launch angle:

This time Fenway made another assist – 429 gets out of a lot of ballparks – but Riley ended up with a double.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Riley can still sting the ball. That power has always been his offensive calling card and the low ISO in 2020 feels more like an aberration than a change. You can see this in the increased exit velocity and the still-very-good barrel and hard-hit rates.

Khris Davis is an interesting comp. From 2018 to 2019, his plate discipline stayed mostly steady (K% up 0.6% and BB% down 0.2%), but his wOBA took a big fall (down .076). He is an interesting case for Riley because he suffered from some of the same issues as Riley.

| Player | FB% Change | HR/FB% Change | LA Change | Avg EV Change | Max EV Change | HH% Change | Barrel% Change |

| Austin Riley (2019-20) | -14.3 | -5.3 | -7 | +1.6 | -0.7 | -1.7 | -3.1 |

| Khris Davis (2018-19) | -11.4 | -6.2 | -5.2 | -2.3 | -2.9 | -8.0 | -7.8 |

Like Riley, Davis saw big drops in his FB% and HR/FB rate. Like Riley, you can see the lost FB% in a big drop in launch angle. But that is where the similarities end. Riley increased his average exit velocity, while Davis’ dropped significantly. Riley saw drops in max exit velocity, hard-hit rate, and barrel rate, but only the barrel rate was a meaningful drop (and all three remained above league average). Davis dropped hard across the board.

This is a pretty good explanation for what happened to Riley on the surface (wOBA not following plate discipline because batted ball results were worse) but while Davis was on the wrong side of 30 and might just be losing his pop, Riley still looks like a guy who can hit the ball hard and hit the ball hard often.

What if He Puts it All Together?

For Riley, “putting it all together” means keeping those plate discipline gains while getting back to the power he showed as a prospect and rookie.

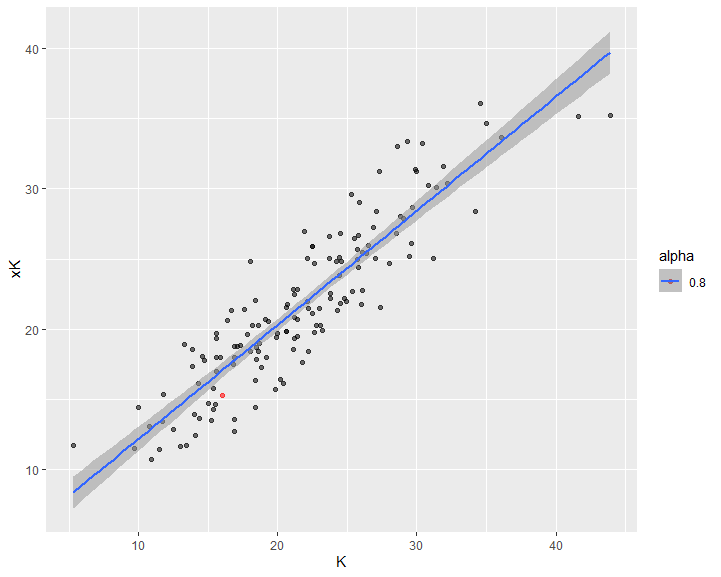

The plate discipline changes look legit. Strikeout and walk rates stabilize relatively quickly, so a 200 PA sample from each season is enough to start to draw meaningful conclusions. In addition, Jack Cecil has done some work on expected K% (xK%) and expected BB% (xBB%). The graph below shows K% vs xK% for 2020. Riley is the red dot – he falls below that line because his xK% (22.2%) was actually lower than his improved K% (23.8%).

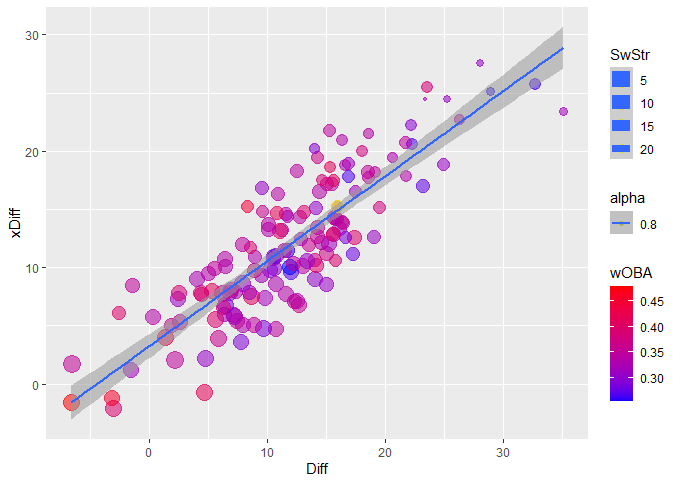

As mentioned, Riley stood out from some other K%-improvers because he also walked more and showed gains in his K%-BB% (from 31% in 2019 to 16% in 2020). Cecil’s work shows that he earned that improvement, as well. This graph shows K%-BB% vs. xK%-xBB% for 2020. In this case Riley is the yellow dot – his expected K%-BB% (15.3%) is again slightly lower than his actual (16%).

As for the power, the only thing he really needs to do is bring his launch back up and, otherwise, keep doing what he has been doing. Going back to the Khris Davis comp, there is some reason for optimism. While Davis’s 2020 continued his downward trend in contact quality, he brought his launch angle back up. If Riley can bring back his launch angle without suffering the likely-age-related declines Davis saw, he should be able to post power numbers that look a lot more like his rookie campaign, if not quite as strong as his first six weeks.

That seems to be what the projection systems see coming. Steamer is projecting a 7.8% BB rate (matching his 2020), 26.5% K rate (keeping the vast majority of his 2020 gains), and a .228 ISO, returning almost all the way to his 2019 power. The 2021 line of his ZiPS three-year projection is a little less optimistic on the plate discipline (7.2% BB rate and 29.1% K rate), but more optimistic on his power (.256 ISO).

But both systems are delivering the same general verdict – Austin Riley showed real growth in his plate discipline in 2020 and he has enough of a track record with his power (and hit the ball well enough last year) to justify an expectation that the power will return.

There is also some precedent for this with Riley. In his first look at AAA, as a 21-year-old in 2018, Riley struggled to make contact (29.3% K-rate) and his power wasn’t what scouts expected (.182 ISO). The overall line in those 324 PA was solid, as he posted a .357 wOBA, but he was reliant on a .374 BABIP. He returned to AAA to start 2019 and in 194 PA not only hit 15 HR with a .333 ISO but controlled the zone much better, striking out only 20.1% of the time and earning a promotion to Atlanta.

Role and Playing Time

While there is justifiable optimism with Riley, the downside to his continued poor performance is that he may not have a job. Riley was almost exclusively a 3B in 2020, though he was more regularly an OF in 2019. While he isn’t great at either, defensive metrics like him a bit better as an OF.

| Position | DRS | UZR/150 |

| 3B | -7 | -9.2 |

| OF | 2 | 6.1 |

Atlanta, meanwhile, has a plethora of outfield options, but Riley seems the obvious in-house answer at 3B. Ronald Acuña will hold down an outfield spot and Cristian Pache will presumably have a second. Ender Inciarte is still around, and Drew Waters is coming up and both are defensively superior to Riley by a wide margin. The only good news for Riley’s playing time is that Adam Duvall was non-tendered by Atlanta today. I don’t think this changes anything for Riley’s chances to start in the outfield, though it may make DH a more realistic landing spot, if the NL has DH in 2021. Put bluntly – Riley isn’t winning an outfield job. There is just too much talent and too many other options.

Johan Camargo is the main internal competition for 3B, but his offense is a major downgrade from Riley (even without potential improvement from Riley). If the universal designated hitter is continued in 2021, which seems likely at this point, that opens up another potential landing spot for Riley.

That is before free agency though. While everyone in baseball is crying poor, Atlanta already went out and paid Drew Smyly and is rumored to be interested in bringing back Marcell Ozuna. It’s possible Atlanta is going to shop for a third base upgrade as well. Even if they are not in the market for Justin Turner or another top free agent, there are a bunch of less expensive options – Jake Lamb, Todd Frazier, Marwin Gonzalez, Tommy La Stella, and a plethora of other names are out there. And I suspect more names will join once we get through non-tenders. None of those guys are exciting, but if Atlanta isn’t sold on Riley, they have options.

And then you have the open question that is the universal designated hitter. Riley might be best suited to DH, but, as mentioned Ozuna may retake that spot, or an upgrade to the outfield could push Duvall to DH.

As of today, Riley has to be considered the favorite and likely starter at 3B, but I don’t think it is a given it will stay that way.

Fantasy Implications

For fantasy managers, there’s a lot to unpack here. Riley has been decidedly not good. Projections think he will be, if not great, very solid. And a very solid Riley in an excellent Atlanta lineup could be really valuable. With an everyday job, he could put up 30 HR and 100 RBI, with OBP and AVG that won’t kill you. That isn’t a league-winner, but at his price, he doesn’t need to be.

Early ADP data suggests you can get him at the tail end of your drafts. Ben Pernick grabbed him with the 387th pick in a recent mock draft. NFBC ADP has him at 240th overall. He’s going 44 picks later than Brian Anderson, and here are their Steamer projected 5×5 lines:

| Player | R | RBI | HR | SB | AVG |

| Riley | 72 | 82 | 30 | 2 | .254 |

| Anderson | 76 | 79 | 22 | 3 | .247 |

I’ll take the under on five combined SB, but otherwise, that doesn’t look like a good use of a 3-4 round premium, especially when Riley is nearly four years younger and plays in a better lineup. I’ll wait on Riley.

In dynasty or keeper leagues that allow off-season trades, he is probably not hard to acquire, particularly if he’s been riding a manager’s bench all season, frustrating him.

There’s risk there, given the 2019 and 2020 performance, but under the hood, he looks like a buy-low who can help you out with significant power. Watch Atlanta this off-season to see what they plan to do. My guess is Riley is in the Opening Day lineup and, if he performs like Steamer and ZiPS expect, he holds down a job all year. If Atlanta pushes him into a platoon or bench role, I would still look to add him in deeper leagues – that power will keep earning him chances and I’ll bet on his talent winning out.

(Photos by Bryan Green/flickr; Graphic by Jake Roy; data support provided by Jack Cecil and Eric Colburn)

You got to predicting his breakout before I did! I picked him up in the TGFBI draft at pick 387! THREE EIGHTY SEVEN! Granted that was the low pick of all leagues, but still it’s crazy how people are giving up on him when he’s still so young and has made so many necessary adjustments.

I don’t know if anyone is giving up on him. However, he strikes out too much and there are many, many better defensive third basemen waiting to get a shot at a title. Some can arguably hit better so Riley at third base for the Braves is no gimme. Maybe he goes?

Looks like the DH in the NL is going away in 2021. Not great for Riley.