Though the Marlins struggled mightily in 2021, Miami fans have reason to be excited about an impressive crop of young starters. Not least among this group is lefty Trevor Rogers, one of 2021’s rookie standouts. The 13th overall pick in the 2017 draft stumbled upon his arrival in the majors in 2020, with an unsavory 6.11 ERA in seven starts. However, a 30% strikeout rate and 3.53 xERA gave reason to believe that better days would come — and come they did. Rogers’ talents were on full display in the first half of 2021, as he posted a 2.31 ERA with a 30% strikeout rate and 8.4% walk rate. The 23-year-old was rewarded with an All-Star nod and pitched a scoreless fifth inning in the Midsummer Classic.

Rogers was limited to only 31.2 IP after the All-Star break due to a devious combination of injury and personal tragedy. In that span, he recorded a decent but far less impressive 3.69 ERA with a 24.5% strikeout rate and identical 8.4% walk rate. Though Rogers’ second half was less flashy than his first, the young lefty showed legitimate talent in 2021 and is poised to build upon his success going forward.

A Strong Foundation

Rogers’ bread and butter in 2021 was his four-seam fastball. He can touch 97 mph with the heater, but arm-side run sets the pitch apart. Rogers throws his fastball with 50 percent more horizontal break than league average — it runs so much that Baseball Savant recorded one of Rogers’ four-seamers from this past season as a sinker. His primary complement to the heater is an impressive changeup. After throwing his change a tick less than his slider in 2020, Rogers upped its usage by nearly 10 percent to make it his go-to secondary offering in 2021. It was a welcome adjustment, as hitters only touched it for a meager .213 wOBA on the season.

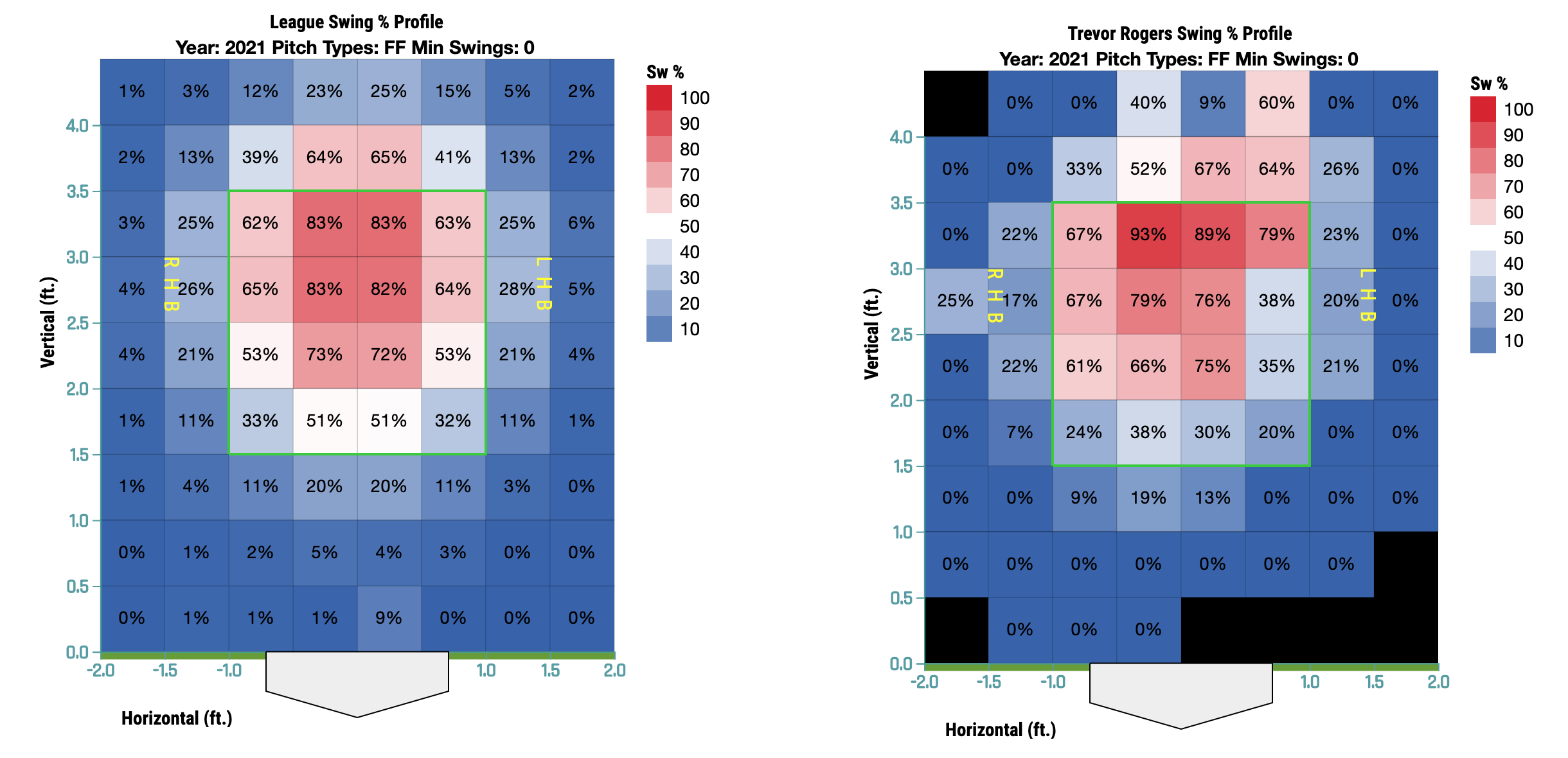

With these two weapons, Rogers was quite effective at getting hitters to expand the zone. Here’s a precise breakdown of where and how often opponents swung at his four-seamer, compared to league average (courtesy of Baseball Savant):

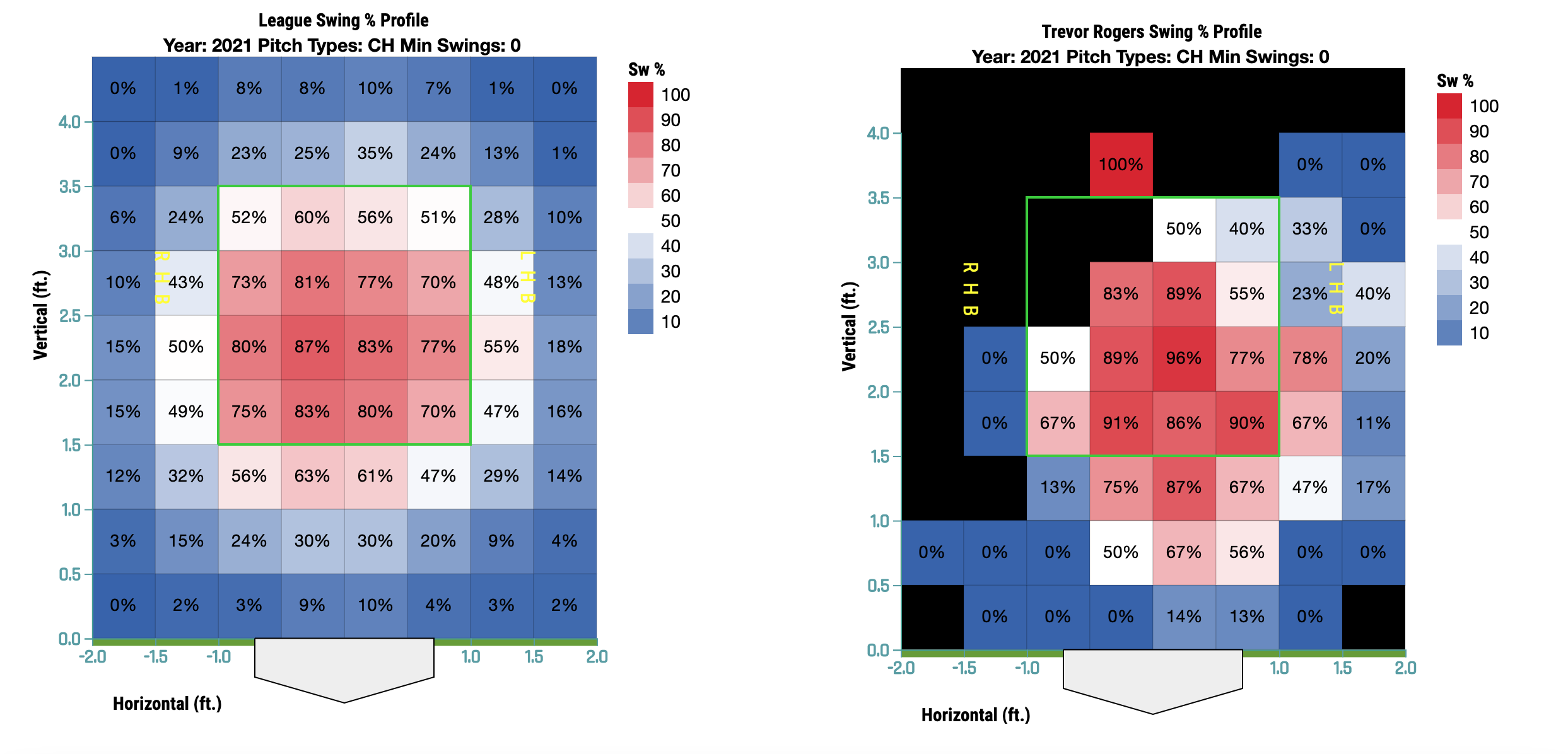

And for his changeup:

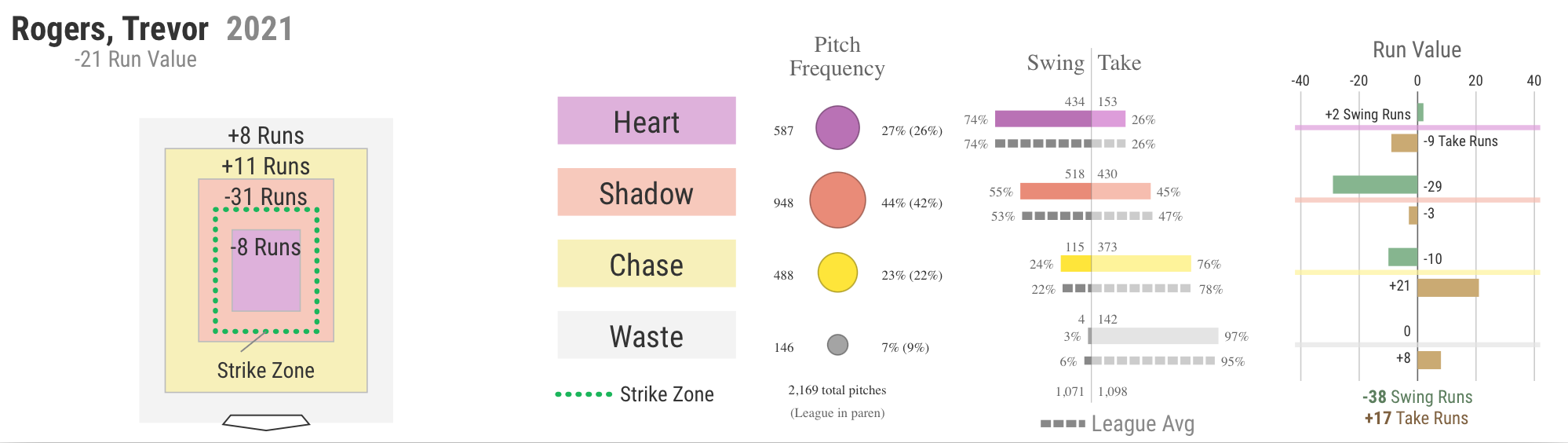

With hitters eager to chase high fastballs and low changeups, Rogers was one of the more productive starters in baseball at working the edges of the strike zone. Baseball Savant’s Swing/Take profile for pitchers takes every pitch a pitcher throws in a season, separates them into four zones, and assigns each pitch a run value based on the outcome of the pitch. For pitchers, the lower the value, the more effective they were. Rogers’ run value in the shadow zone (the edges of the strike zone) in 2021 was an impressive -31 runs.

Out of 300 pitchers (both starters and relievers) who qualified for Baseball Savant’s Swing/Take leaderboard, Rogers’ -31 run value in the shadow zone was 20th-best, flanked by names such as Marcus Stroman, Lance Lynn, Chris Bassitt, and Adam Wainwright. Run value is a volume stat, and Rogers accrued his high mark in considerably fewer innings pitched than many of the names around him on the leaderboard.

Rogers’ ability to expand the zone with heaters up and offspeed pitches down mimics the success of another one of 2021’s premier arms. Kevin Gausman enjoyed a career year with the Giants while leaning heavily on two pitches, a four-seamer with well-above-average vertical break and an elite splitter. Like Rogers and his change, Gausman pounded the lower part of the zone with splitters, tempted opponents to frequently chase pitches below the zone, and racked up an absurd 45.8% strikeout rate on his split. The two NL All-Stars—in fact, Rogers noted that a conversation he had with Gausman was one of the highlights of his All-Star experience—also compiled high strikeout rates thanks to legitimate whiff ability (both 81st-percentile whiff rates). Their successes show the upside of an approach centered around a good fastball and a strong offspeed pitch.

Elevating fastballs and burying changeups is also a good recipe for suppressing hard contact, another of Rogers’ talents. Detractors might point to Rogers’ 5.0% HR/FB rate as evidence of good fortune in 2021, but a 65th-percentile hard-hit rate and 89th-percentile barrel rate give credence to his home run suppression. Such a low HR/FB% may not be sustainable, but with Rogers’ evident ability to limit hard contact and a home park that’s favorable for suppressing homers, there may not be as much regression as one might think.

Room to Grow

One improvement Rogers can make is to find a more effective third pitch. Right now he has a slider with a slightly below-average vertical break, but only 1.7 inches of horizontal movement, 79% less horizontal movement than league average. With the run on his changeup and fastball, it’s enough to give hitters a different look from those two pitches, but it leaves Rogers without a pitch that truly breaks away from same-handed hitters. The slider was arguably Rogers’ least effective offering in 2021:

Though the slider was Rogers’ best whiff pitch, he struggled to convert those whiffs into strikeouts. His overall results with the slider weren’t disastrous, but the expected stats paint a less rosy picture. Though the slider was more effective at getting whiffs against righties than lefties (44.9% whiff rate vs. RHH, 35.3% vs. LHH), Rogers showed righties the pitch considerably less often than lefties.

This leads us to pitch mix and the limitations of Rogers’ arsenal. 45% of the sliders Rogers threw all season came in 0-0 counts; otherwise, he was heavily a two-pitch pitcher. The same was true of how he attacked righties, who saw either a fastball or changeup almost 90 percent of the time. Lefties, however, saw the slider more often than the changeup, despite the latter’s universal effectiveness (.211 wOBA vs. RHH, .221 wOBA vs. LHH).

In other words, Rogers played to his strengths against righties more so than against lefties. His righty-lefty splits, then, aren’t entirely surprising:

Roughly equal strikeout rates against righties and lefties are encouraging. But more walks equals more offensive production, and the difference between righties and lefties in that regard was significant. The slider wasn’t the only culprit, either. Lefties had an easier time than righties laying off both sliders and heaters that Rogers threw out of the zone (and changeups, though the difference is negligible):

Ultimately, Rogers’ arsenal and current approach work better against righties than lefties. The data suggest that showing the change to lefties more often and upgrading his slider are paths for improvement. To explain how he could approach the latter, we’ll dive into a new, fascinating analytical tool: spin direction.

The Spin Zone

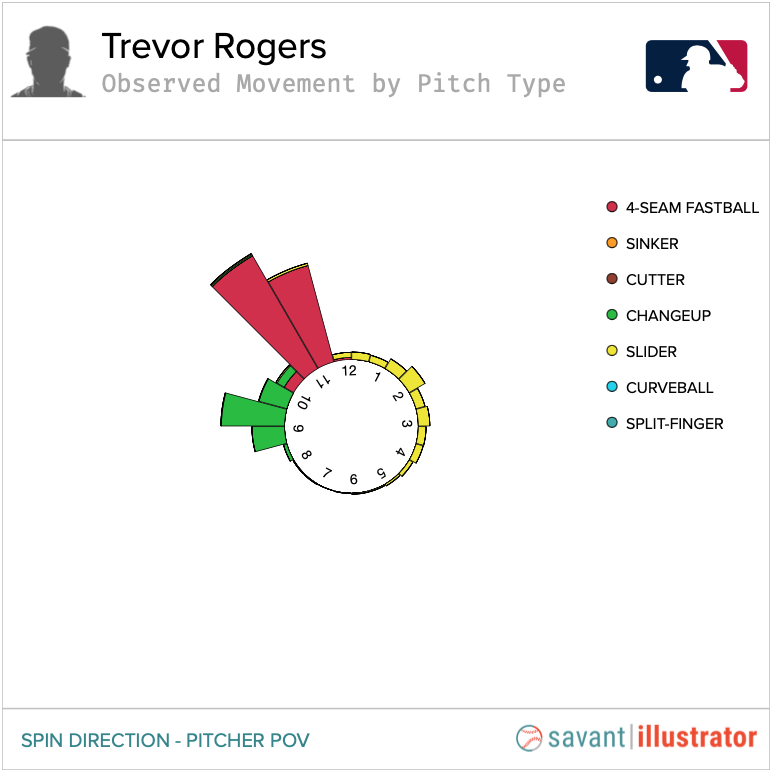

Last year, Baseball Savant added spin direction metrics to their pitcher pages. Using Hawk-Eye camera data, they accurately measure the direction in which a pitch spins and express it as a time on a clock, as observed from the pitcher’s point of view. For example, a fastball with a measured spin direction of 12:00 would look like it’s spinning from 12:00 to 6:00 on a clock face from the pitcher’s perspective. Measured spin direction refers to the spin as measured out of the pitcher’s hand, while observed (or inferred) spin direction is the direction of spin as inferred by how the pitch moves when it arrives at the plate.

Spin direction is far from the be-all, end-all of what makes a pitcher good, but it can be a useful tool to help explain why good pitchers are effective. This comprehensive piece by Mike Petriello is an excellent primer on spin direction and how pitchers can use it to their advantage. One concept Petriello discusses is throwing multiple pitches that have the same, or nearly the same, measured spin direction (i.e. look similar out of a pitcher’s hand) but deviate in observed spin direction (i.e. break differently when they get to the plate). This concept sheds more light on why Rogers’ fastball-changeup tandem works so well.

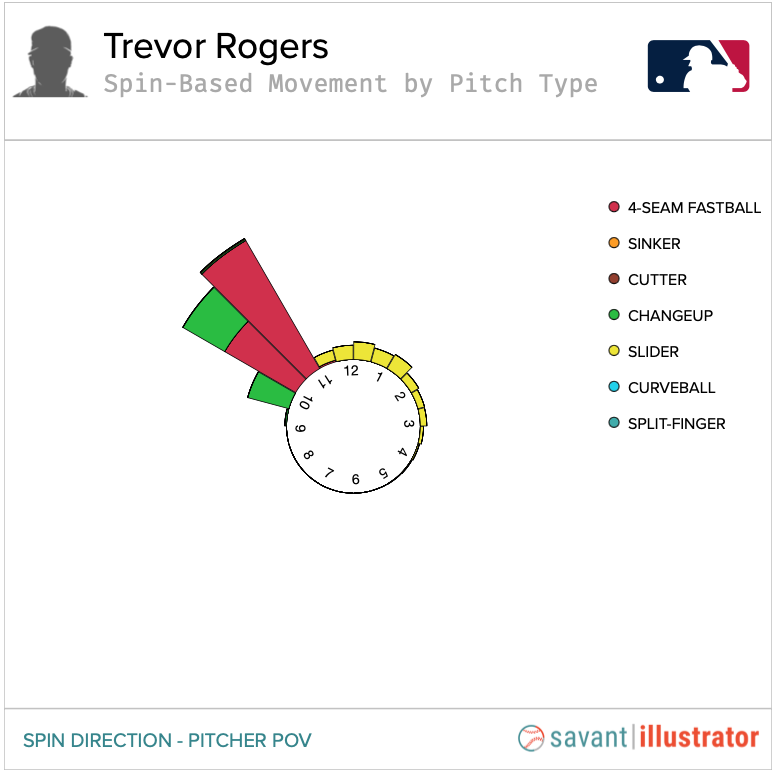

This chart visualizes the measured spin direction of Rogers’ three pitches when they leave his hand:

The average measured spin direction of Rogers’ heater was 10:15, and the measured spin direction of his change was 9:45. That’s not identical, but it’s pretty dang close, and it’s enough to look very similar to a hitter. By the time they reach the plate, the pitches have veered off in different directions. The observed spin direction of Rogers’ heater was 10:45, compared to 9:00 for his change:

Here’s what the two offerings look like playing off each other:

Trevor Rogers, 96mph Fastball (foul) and 87mph Changeup (swinging K), Overlay. pic.twitter.com/c9IWj8Z5fw

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) May 7, 2021

The above charts also show that the spin direction of Rogers’ slider is distinct from that of his other two pitches. That doesn’t automatically make the pitch a bad one, but a little deception could go a long way. To get back to a third pitch for Rogers, we’ll turn to another concept from Petriello’s article: pitch mirroring.

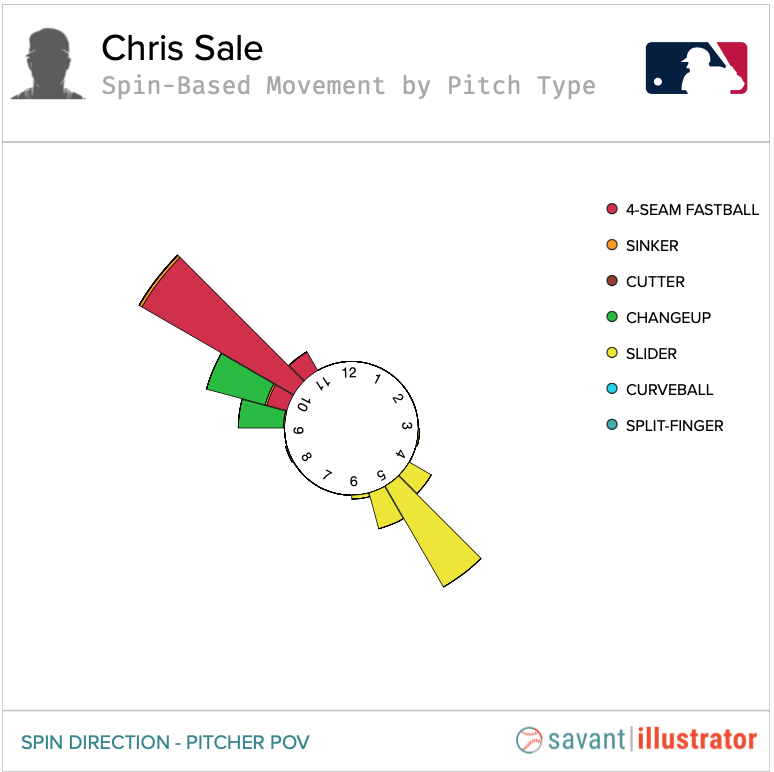

A fastball with a spin direction of 12:00 and a curveball with a spin direction of 6:00 would perfectly mirror each other. They would be spinning on the same axis, but the fastball would have backspin while the curve would have topspin (and at upwards of 2000 rpm, could you tell the difference in just a split second?). Pitch mirroring is another way a pitcher can use spin to trick hitters, and changing the spin direction on Rogers’ slider could be a way for him to take a step forward. Red Sox ace Chris Sale has an arsenal that illustrates this possibility:

This past season, Sale’s four-seamer had a measured spin direction of 10:00 and an observed spin direction of 10:15, while his change had a measured spin direction of 9:15 and an observed spin direction of 9:00. That’s not as similar out of the hand nor as much of a deviation at the plate as Rogers’ heater-change combo. Sale’s slider, however, has a measured spin direction of 4:30, which plays very well off the spin direction of his fastball. 10:00 vs. 4:30 isn’t perfect pitch mirroring, but again, it’s pretty dang close, and it’ll certainly give hitters fits.

If Rogers threw his slider with a measured spin direction of 4:30 like Sale, it would mirror his heater (measured spin, 10:15) very well. If he threw it with a measured spin direction of 4:00, it would closely mirror his heater and his change (measured spin, 9:45). To reiterate, there are many factors other than spin direction that make a pitch (or pitcher) good and I’m not claiming this would turn Rogers into Sale 2.0. But throwing a third pitch that blends in with your other very good pitches? Yeah, that sounds like it would be worth a shot.

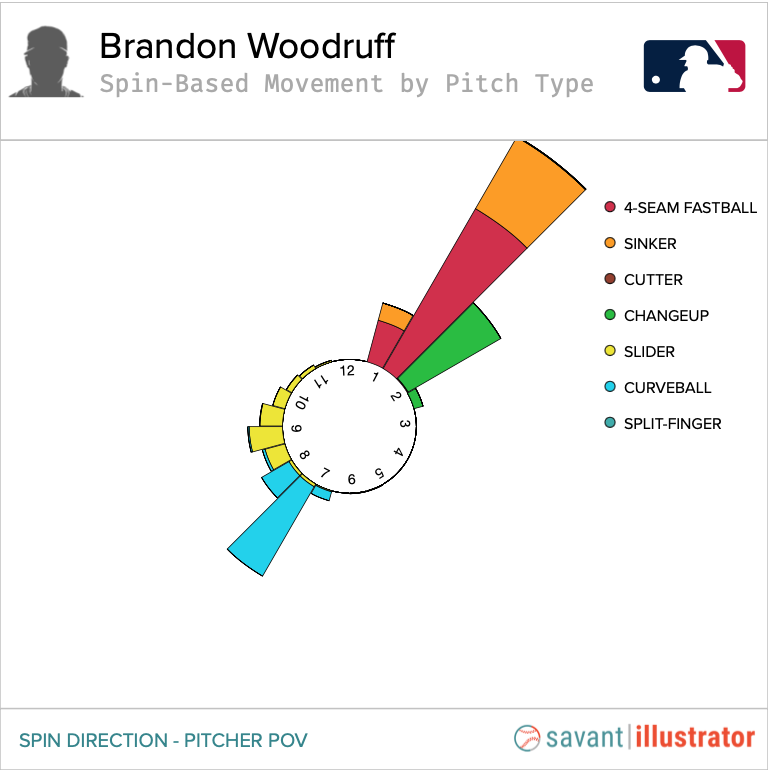

One pitcher who did just that in 2021 is Milwaukee righty Brandon Woodruff. Woodruff throws three pitches within 0:30 of each other in measured spin direction: his four-seamer, his sinker, and his changeup. This past season, his curveball became another potent weapon. He had the curve before 2021 but rarely threw it, and the pitch was mostly a non-factor. This past season, he upped its usage from 6.4% in 2020 to 16.7%, making it his most frequent non-fastball offering. The results spoke for themselves, as Woodruff recorded a 40.5% strikeout rate, 31.8% whiff rate, and .181 opponent wOBA on his hook. Its spin, as you may have guessed by now, closely mirrors his four-seamer, sinker, and change:

Woodruff’s success throwing his curve more shows what Rogers could gain with a breaking ball that mirrors his fastball and changeup.

Looking Ahead

Arguably the most important number to remember when talking about Rogers is 24: his age going into the 2022 season. He’ll be due for a healthy bump in innings, which may lead to some natural growing pains and unforeseen adjustments. Even so, his fastball and changeup give him an excellent foundation, especially considering how well the two pitches play off each other and against opposite-handed hitters. With a great fastball and terrific changeup, Rogers has established himself as a solid SP2 with an ERA in the mid-3s, legit strikeout ability, and a talent for home run suppression. If Rogers can hone a breaking ball to use as yet another weapon, possibly with the help of spin direction, he could be on his way to a sub-3 ERA, even gaudier strikeout totals, and bona fide ace status.

Photos by Jeff Robinson/Icon Sportswire and Egor Vikhrev/Unsplash | Adapted by Ethan Kaplan (@DJFreddie10 on Twitter and @EthanMKaplanImages on Instagram)