Eddie Rosario is one of the best bad ball hitters in all of baseball. Over his years with the Twins, it’s become his signature move — while the rest of the Twins lineup has become known for drawing out ABs, taking walks, and forcing a pitcher to work for his outs, Rosario swings freely and makes enough contact for it to work out for him. At times, it has made Rosario look silly or prone to long slumps. At other times, Rosario does things like this:

Just a bit outside. 😏#MNTwins pic.twitter.com/sphILFH5sn

— Minnesota Twins (@Twins) August 4, 2020

or this:

🗣 EDDIE

🗣 EDDIE#MNTwins pic.twitter.com/ajFZ0Q1lze— Bally Sports North (@BallySportsNOR) August 1, 2020

This plate approach can make Rosario fun to watch, but he’s infuriating to have on a team. Part of every manager just knows that if Rosario ever loses bat speed, pitchers would be able to take advantage and render him useless. Fortunately, Rosario is changing.

Rosario’s New Approach

In the offseason this year, Rosario repeatedly committed to taking more pitches this year. In an interview Rosario gave, he told reporters that “I love being aggressive, but I want to help the team.” Aaron Gleeman of The Athletic also reported Rosario saying, “That’s one of the goals this season. Just to be more selective with pitches. When I swing at good pitches, my numbers are there. So I’m just going to concentrate on that and try to keep getting better.”

Fortunately, Eddie has made good on his word. Nearly every single plate discipline metric of his is dramatically improved his year, with Eddie going from one of the worst in baseball in many plate discipline statistics to above average.

| Season | K% | BB% | 1st Pitch Swing % | Chase % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 17.60 | 5.10 | 61.50 | 41.60 |

| 2019 | 14.60 | 3.70 | 59.50 | 43.00 |

| 2020 | 10.70 | 12.50 | 51.80 | 34.60

|

These numbers are amazing! Rosario has decreased his strikeouts, over tripled his walk rate, and significantly decreased other swing rates. Everything we can see here points towards a rousing success for Rosario as far as his offseason changes go. In the past, when Rosario has approached the plate in a patient way, it has led to great success for him.

One statistic, which I originally heard reported by Justin Morneau and later saw repeated by Aaron Gleeman, does a great job of encapsulating that: “In the months when Rosario swung at more than 40 percent of pitches outside the strike zone, his OPS was .713. When he swung at fewer than 40 percent of out-of-zone pitches, his OPS rises to .838. And when Rosario swung at fewer than 35 percent of out-of-zone pitches — just six months across five seasons — his OPS jumped to .918.” So far this season, Rosario’s chase rate is at 34.6%. That would put him in the same bucket of plate discipline as when he has put up a .918 OPS in the past. For a player whose wRC+ in 2019 was only 103 with an OPS of exactly.800, that’s a significant jump.

Rosario’s Failures

Unfortunately for Rosario, that change hasn’t yet quite worked out how he wanted it to. For the most part, his numbers up to this point of the year have been downright hard to look at. Rosario’s slash line stands at .208/.300/.415, resulting in a .715 OPS that’s over 200 points lower than we had hoped for.

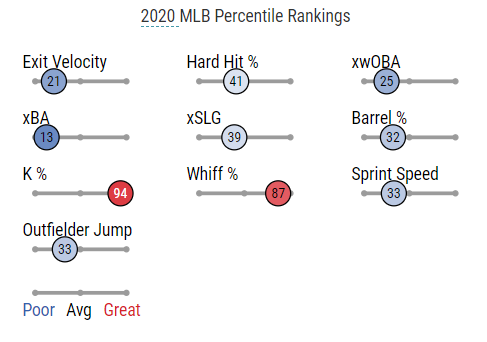

Those numbers do take a while to stabilize, so it’s not necessarily helpful to look at them and come to any significant conclusions yet. Rosario does have a .182 BABIP, and his ISO is right near his career norm. What is concerning is how much difficulty Rosario is having hitting the ball hard, which we can see from his Baseball Savant page.

Rosario has never had difficulty in the past with these numbers. He’s never been an outlier, like his teammate Miguel Sano, but in 2019 he had a solidly above average 89.2 mph average exit velocity. Thus far this year, that number is 84.7. That number can be misleading on occasion (especially when comparing players) but it does show that on average Rosario isn’t driving the ball as well this year.

Fortunately, average exit velocity isn’t the only statistic we have to measure Rosario with. In fact, nearly every metric that measures Rosario’s quality of contact is down precipitously. Rosario’s sweet spot %? The metric dropped from a healthy 33.4% to an abysmal 20.9%. His xWOBACon fell from .388 to.235. And his hard hit% crashed by a full 10%.

Clearly, something isn’t working out for Rosario, as these results are utterly perplexing. He finally did what all analysis had hoped he would do, and yet, instead of having something to show for it, he’s produced his worst season to this point in his career. Ultimately, Rosario’s struggles may have come down to some of us confusing correlation and causation. It’s possible that Rosario didn’t succeed in past seasons because he was swinging outside the zone less often but instead, he swung outside the zone less often because he was hot and playing well with the pitches within the strike zone.

A Closer Look

In June 2018, Eddie Rosario was on fire. That month he slashed .330/.395/.689 and hit nine home runs. Everything that pitchers were throwing, Eddie was hitting — and demolishing. It’s also when he featured a chase rate of 31.1%, the lowest its been in his career. Most exciting to me, however, was his spectacularly low 10.5% whiff rate.

Rosario’s approach that month hadn’t changed; he was simply hitting more pitches early, before he had a chance to fall behind in the count and before pitchers could force him to change. That slash line is amazing, and the OBP is excellent, but its propped up by his .330 average. He walked slightly more than normal for him that month, but it was still below MLB’s average walk rate. Under the hood, there were no significant changes either: Rosario still swung well over half the time, closer to his career norms than his numbers in 2020.

As some look at Rosario’s chase rates this far into 2020 and think that he’s repeating that month in 2018, I’d like to caution you from believing that. This is a whole new Rosario.

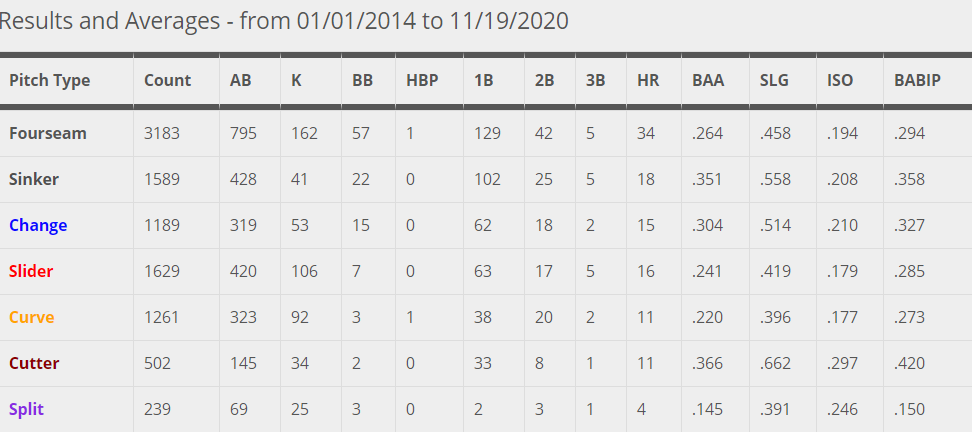

This Rosario has a swing rate against fastballs and sinkers has never been lower than it has this season. Meanwhile, he’s swinging more than ever at sliders and curveballs. This isn’t a good thing. After all, the slider is the toughest commonly thrown pitch to hit and a high swing rate on curveballs for a batter who struggles with plate discipline doesn’t seem like a recipe for success, either.

Indeed, Rosario has been significantly worse against breaking balls in his career, which we can see in this graphic from Brooks Baseball. If this is how Rosario’s plate approach is going to change, I don’t want it. Allowing Eddie to jump on an early fastball was never the problem — he performs well against four-seamers and excellently against sinkers and cutters. Instead, Rosario needed to learn to take more curveballs and sliders, pitches pitchers struggle to place in the zone, and which Rosario struggles to hit.

This year he hasn’t improved his plate approach. He’s simply taken a concerted effort to become less aggressive. When pitchers are able to sneak an early fastball by him and force him to swing at sliders and curveballs that they’ve completely fooled him on, they’ve won the first part of the plate appearance and gained a huge advantage.

It’s painful for me, a lover of walks, to say this, but Eddie Rosario needs to revert back to his old self. He doesn’t need to do so completely: keeping his chase% down seems like it doesn’t really have downside, but by and large, his changes this season have been harmful rather than helpful.

It’s not all bad, however. In the last few days, we’ve seen some of the potential of what Rosario could become. Rosario hit three home runs in a series this week against the Brewers. Twice, he did so while leading in the count, a time where we saw the potential upside that his new plate approach could lead to. If he can take balls early, he’ll force pitchers to throw the fastballs in the zone that he hits so well.

The other ball he hit out, however, was on a 0-0 count. Adrian Houser left a ball hanging in the zone and Rosario crushed it over the center-field wall for a grand slam. This is the kind of Rosario I want to see, a Rosario that is willing to take breaking balls early but swing at the balls he can mash. Eddie doesn’t need to lead the league in walks. That’s not his game and it’s not a strong suit for him. All Rosario needs to do is get ahead in the count more often so that he can better dictate the pitches thrown.

Overall, Rosario is a tough player to project into the future. If he continues to be passive early in counts, it’s likely he could continue to struggle. If he reverts back to 2019 Rosario, he’ll be okay, but nothing special. If, however, he manages to find the magic middle ground, he could reach the next step. I hope he can do so.

Photo by Larry Radloff/Icon Sportswire

Good analysis. I have always been a Rosario guy but I am not certain that he has taken a step forward. Maybe he has taken some steps, maybe not. One thing is for sure and that is that you undervalue what he was. Only a computer would say he was nothing special (103 wRC+) last year. A respectable AVG and 25+ HR with potential for mid 30s on a regular basis is pretty exclusive company in today’s game, which I would characterize as being full of AAAA sluggers. Walks are greatly overvalued and the ability to put the bat on the ball is undervalued. I prefer him to Kepler in his ability to provide a competitive at bat and help his team win. Isn’t it comical that Eddie has a career high in wRC+ at the moment? New school analysis clearly has lots of problems. Your ability to understand that will determine how good at this you are. Those improvements are so dramatic that you know there is a lot of noise in there. I am certain that hard% is not a good stat with this little data. Just think about the frauds that always emerge as breakouts around this point in any season – thanks a lot Statcast. If he really was being smarter would his batted ball metrics really decline like that? You have to think that he is considering reverting back to what has worked in which case it is all noise and this entire discussion could become a distant memory. You don’t seem to be considering that those batted ball metrics all amount to nothing. They probably do. He probably is in spring training shape and there is probably more noise than consistency in all that data. As an additional wrinkle, I always figured he was a juiced ball poster-boy. If the ball is in fact real again he could be paying that tax. It would be great if he really made some lasting changes, but I am always skeptical. In this day and age, the profit is made on skepticism as people cling to every fad and act on every trending idea. One thing is for certain, you can’t change significantly and have everything positive from before to go with it. That is the common misconception of “analysts” that don’t know the first thing about playing actual baseball. Git gud, right? I think I used that term right. That said, I think anyone can improve their approach – it should be incremental though.

Perhaps one of the reasons that Rosario swings so much is that his pitch identification is trash. I would say that he might have above average hand-eye and below average pitch identification skills. In fact, that is exactly how I would classify him. Maybe that is why he isn’t swinging at the right pitches which is likely what you are trying to point out with numbers. At the end of the day, I think this is really good analysis. I expected you to be fawning over his BB rate but you didn’t. I have no idea what to expect our of Rosario this year. Interestingly, I have always had a little mental list of guys I figured were juice ball beneficiaries and they are all eating it this year. I think the de-juicing the ball narrative and analysis is trash at this point. It will be some time before we get some decent data on that. I won’t accept it this year as this is just spring training masquerading as MLB baseball. Lots of guys that had pedestrian power but had been hitting for significant power the past few years are really struggling this season. I do not care to speculate as to how juiced the ball isn’t as I just don’t think this is real baseball and that probably matters as much as any data that someone mines. I have a suspicion that there will be a lot of hitters falling on their face this year.. more than normal. How can you not attribute that to the crazy season, but it is also likely the balls. Since I am going full rant mode, I suspect the Statcast data to start shifting its narrative to defense and pitching. AWS got embedded advertisements for juicing the balls and Google Cloud will profit from changing the balls yet again. The narrative will be look at how big data makes athletes better but it is just manipulating the underlying physics and the resulting effect on the outcomes. It is worth understanding that all the progressive fans are getting played like a banjo. Don’t take progressive metrics too seriously, they are closer to a joke than insightful. They are literally revised every year – there is literally zero accountability.

Thank you for the comment! I’m glad you enjoyed the analysis. There’s a lot here that I’m not entirely sure how to respond to, but there is one thing I wanted to touch on. I think a lot of us use advanced statistics inappropriately and end up doing more harm than good with them.

A lot of the best advanced statistics help reflect what we can see happening. CSW (the called strikes and whiffs statistic that Nick Pollack developed here) makes a lot of sense because it reflects what we see. When a pitcher looks dominant and makes a lot of players look silly, it tends to look good in the metric. Same with maximum exit velocity – when I saw that Sano frozen rope home run last week, it showed me that he has a lot of potential power.

The numbers that are harder to see (something like average exit velocity, where its *really* visually hard to tell the difference between 10 balls hit at an average of 87 MPH and 10 balls hit at an average of 91 MPH) are generally numbers that more people – even analysts – struggle to use correctly. I recall our own Alex Fast being part of a twitter thread the other day talking about how average exit velocity isn’t very statistically predictive and yet its often the first thing baseball savant users look at.

I have a real appreciation for some advanced statistics, but a lot of good analysis is knowing when they’re not helpful and not to use them.

I’m a huge Twins fan, and have been frustrated with Rosario in previous years because he is so streaky. This year I’d just like him to go back to what worked. That seemed to have a far better upside. Great analysis, Josiah. I can see why your articles often lead on the front page of the site.