No one was expecting Yusei Kikuchi to be Shohei Ohtani. Nor Yu Darvish nor Masahiro Tanaka. He wasn’t supposed to seamlessly transition from Nippon Professional Baseball to Major League Baseball and immediately dominate. He wasn’t seen as an ace but rather as a strong middle-of-the-rotation arm with upside.

Still, an ace is exactly what he was over his eight-year career with the Seibu Lions. Kikuchi peaked in 2017, going 16-6 with a 1.97 ERA and a 29.5% strikeout rate. His 2018 follow-up wasn’t as impressive, as Kikuchi dealt with a variety of minor shoulder ailments, but it was still good nonetheless:

| Year | W-L | IP | ERA | WHIP | K% |

| 2017 | 16-6 | 187.2 | 1.97 | 0.91 | 29.5% |

| 2018 | 14-5 | 165.2 | 3.08 | 1.04 | 23.5% |

Even with a subpar (for him) 2018, it was no surprise Seattle spent big on his rights given its history with Japanese stars—and given Jerry DiPoto’s proclivity for acting like a fantasy GM with an itchy trigger finger.

And so the next Japanese star came to America looking to make his mark on MLB.

Going Transcontinental

After a career year in 2017 and a follow-up season that was still very good, how has Kikuchi fared in his first 100-plus innings in the majors?

| Kikuchi | W-L | IP | ERA | WHIP | K% |

| 2019 | 4-7 | 114 | 5.21 | 1.46 | 16.6% |

Oof. Perhaps no one was expecting Kikuchi to be the next great Japanese pitcher, but they were certainly hoping for something better than left-handed Ivan Nova. Think the Nova comparison is too harsh? Don’t.

| Nova | W-L | IP | ERA | WHIP | K% |

| 2019 | 6-9 | 125.2 | 5.23 | 1.44 | 15.0% |

These are usually numbers that you want to designate for assignment, not spend $100 million on. What happened? Where did the wheels come off?

Before we dig into the stuff of the man, it’s important we first take note of the man behind the stuff. And to the mind behind the man.

A Curious Mind

Now 27 years old, Kikuchi has seemingly had his eye on the MLB since graduating from Hanamaki Higashi High School—just as incoming freshman Ohtani was arriving. After his career year in 2017, Kikuchi turned his eye to MLB, going so far as to hire an outside analytics firm prior to his final season in Japan in preparation for the move. Besides the tangible benefits of such a move, this also speaks to Kikuchi’s intellectually curious mind and his desire to improve.

Using the Trackman data that was now available from all stadiums in NPB, Dr. Tsutomu Jinji—a professor of biomechanics and a leading researcher in pitch movement—worked with Kikuchi to maximize his current pitches as well as to find a new pitch to take stateside. While using data in this way is becoming more commonplace in the American game, this is not considered normal among Japanese players, as Dr. Jinji explained in an interview in April.

And so besides refining the fastball, slider, and curveball he already had, Kikuchi and his team looked for another weapon to forge. The sinker got a small audition in that final NPB season, but it was the changeup—a pitch Kikuchi would grill noted techno-pitch-wizard Trevor Bauer about when they would later play—that was ultimately given the rose and taken to the MLB fantasy suite. Kikuchi referred to them as “practice pitches” during that last season, but practicing this pitch may be the key to unlocking his true potential.

And so Kikuchi arrived in the United States with three checked bags of pitches and a changeup that was more of a carry-on.

Luggage Lost

1. Changeup: Kikuchi was initially said to have a variety of breaking pitches but would mostly feature a slider, curveball, and split-finger. But it turns out that those initial scouting reports were actually speaking about the new changeup. And while Kikuchi has thrown it less than 5% of the time in 2019—and only to righties—it has nevertheless found success in its limited usage and going forward could be an effective weapon of choice.

https://gfycat.com/unlawfulcarelessdogwoodtwigborer

| MPH | USE | Zone% | Chase% | SwStr% | CSW |

| 84.8 | 5.0% | 29.1% | 35.7% | 16.5% | 20.3% |

Once again, a very small sample; but you can see above and below why there’s hope that Kikuchi can develop the changeup into another plus pitch or at least the above-average one that he desperately needs.

| Brl% | BA | xBA | SLG | xSLG | wOBA | xwOBA | K% | BB% |

| 6.3% | .091 | .226 | .091 | .335 | .080 | .240 | 18.2% | 0.0% |

The Showpiece

2. Slider: Kikuchi’s best offering by far, the slider is what led to preseason comparisons to fellow lefty free agent Patrick Corbin. While no one was saying that Kikuchi was Corbin, they were saying that the slide-piece was filthy.

https://gfycat.com/imperfectquaintincatern

Coming to America, the slider has been as advertised. Don’t trust me, just ask Yoan Moncada.

https://gfycat.com/likablecomplexfluke

| MPH | Zone% | Chase% | SwStr% | CSW% |

| 86.1 | 46.7% | 42.9% | 16.1% | 22.9% |

| Brl% | BA | xBA | SLG | xSLG | wOBA | xwOBA | K% | BB% |

| 7.9% | .229 | .183 | .421 | .317 | .315 | .262 | 27.2% | 8.9% |

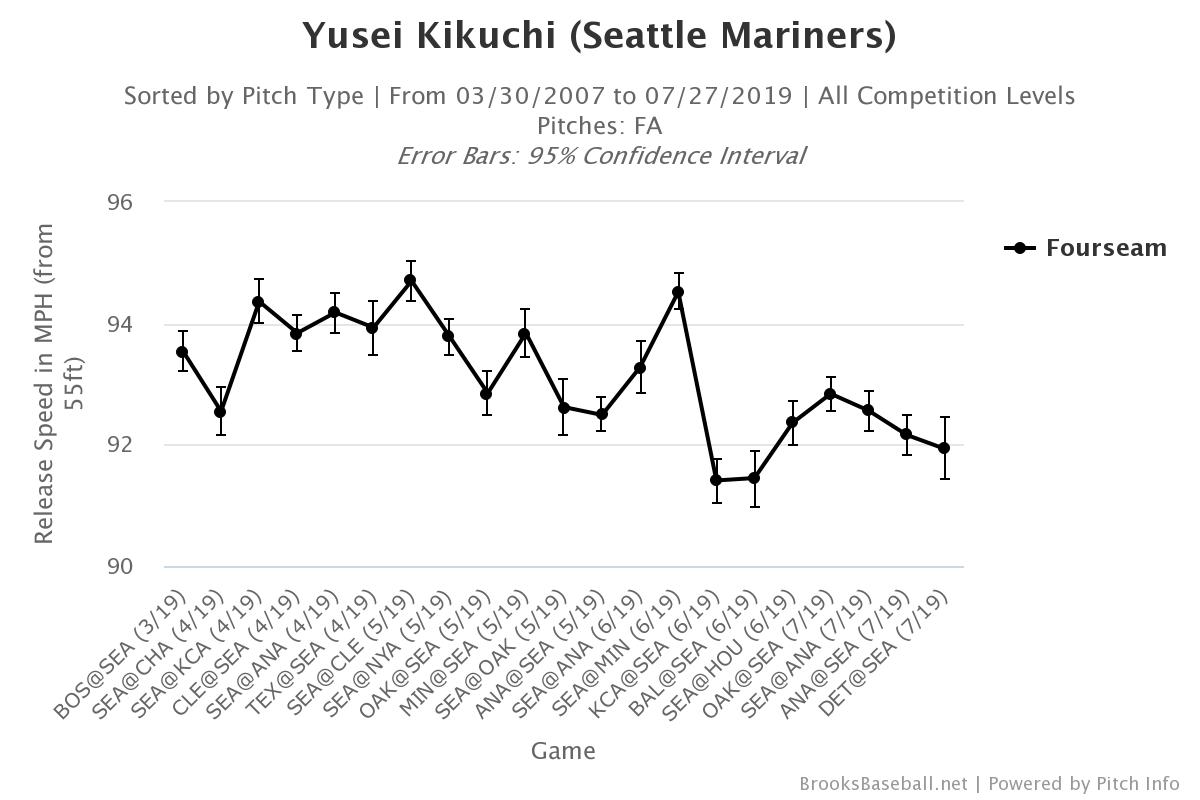

Formerly Fast, No Longer Furious

3. Four-Seam: Kikuchi’s velocity in Japan was atypical, sitting 92-94 mph and could run up to 95-97 mph. Which would play just fine here, with the fastballs of left-handed MLB starters averaging 91.4 mph in 2018. How’s it so far?

| MPH | Zone% | Chase% | SwStr% | CSW |

| 92.7 | 57.6% | 19.1% | 7.2% | 24.2% |

The average velocity looks as expected, but no one’s chasing and no one’s missing. This is not particularly great considering how often Kikuchi is in the zone. In fact, of starters who throw their four-seamer 50% of the time or more, only five have a higher zone rate than he.

Given how often Kikuchi is in the zone with his heater and how few swinging strikes he’s getting with it, the results are about as you’d expect.

| Brl% | BA | xBA | SLG | xSLG | wOBA | xwOBA | K% | BB% |

| 7.8% | .337 | .306 | .607 | .530 | .418 | .390 | 10.3% | 9.9% |

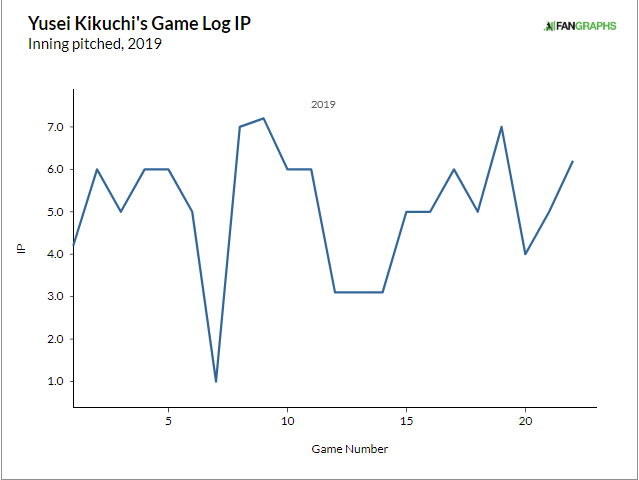

Is this the fatigue that comes from pitching every fifth day in the majors after pitching once a week in Japan? The Mariners claimed they had a plan for dealing with this transition, part of the reason that Kikuchi ultimately chose Seattle, in which Kikuchi would be a normal part of the rotation but would only be used for an inning or two every fifth or sixth start. Which is what happened the first time through, with Kikuchi pitching one inning as an opener in his seventh start. And after that?

And how has the velocity held up?

Regardless of the Mariners’ plan for his transition, it seems that fatigue has come for Kikuchi. His average velocity continues to drop, but more troubling is that the top speeds from Japan never really showed up, as Kikuchi has only topped 96 mph six times this year. You don’t need to be told that a faster fastball will probably perform better, but how exactly has Kikuchi’s heater worked at different speeds?

| % of FB’s | MPH | Whiff% |

| 0.7% | > 96 | 50% |

| 17.5% | 94-96 | 11.2% |

| 49.1% | 92-94 | 7.7% |

| 27.9% | 90-92 | 5.1% |

Considering how often he’s in the zone with the fastball, every little speed uptick counts, and it’s just not happening enough.

A Hitch in His Matrix

Kikuchi is a known tinkerer, seemingly whether a problem may or may not exist. Take the hesitation in his motion, for example. A distinct pause before he moves toward the plate. But sometimes the hitch disappears.

Against Josh Reddick on June 29:

https://gfycat.com/impeccablejadedimago

Against Michael Brantley, in the same game:

Mike Trout gets the hitch in April:

https://gfycat.com/somberbrightgosling

But not in June:

https://gfycat.com/tartgleefulamurstarfish

It comes back on July 14:

https://gfycat.com/babyishsomeborzoi

But a week later, Trout gets a little of both. A hitch for his first two at-bats:

https://gfycat.com/jitteryharmlessconure

But not for his last:

https://gfycat.com/graciousglisteningflounder

The larger point is all the moving parts that go into Kikuchi’s motion are already a lot to deal with, but when you add in a variance from batter to batter and from game to game, you can see why consistency of motion could snowball into a large problem. Which is what Kikuchi has with his final pitch.

Bang-A-Rang

4. Curveball: Batters have not been kind to Kikuchi’s hook, banging it around almost as if they know it’s coming. Much like his fastball, Kikuchi’s last offering is not a swing-and-miss pitch and does not induce much chasing. While it does have the highest called-strike rate of any of his pitches—and consequentially the highest CSW% as well—the curveball has been received poorly by the MLB.

Release Me!

Ever since I saw my first overlay GIF from Pitching Ninja, the importance of release points and arm slots has always stayed on my mind. Besides, aren’t they just the coolest? Behold, as Darvish turns one pitch into five:

https://gfycat.com/bewitcheduncomfortableastrangiacoral

When every pitch is coming out of the hand at the exact same point and the exact same spot in a pitcher’s delivery, then you’re giving the batter the least amount of information possible about what pitch is coming, therefore giving yourself the most advantage. And with Kikuchi’s funky delivery, I figured maintaining the consistency of his release points had to be difficult, right?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18326944/Yusei_Kikuchi.png)

Nicholas Stillman already looked at this issue, showing that Kikuchi’s release distance—where a pitch is released out of hand relative to his other pitches—were some of the worst in the league. The league average release distance for any pair of pitches is 2.6 inches. Not only do all of Kikuchi’s pitches have a release distance over 3 inches, but his slider and curveball are a massive 6 inches apart.

Six inches is a lot of space for a hitter to be able to recognize whether he’s getting Kikuchi’s best pitch (the slider) or a curveball that’s in the zone 49.5% of the time. Let’s look at Kikuchi’s curveball numbers through the lens of a hitter who recognizes those 6 inches and decides early on he’s probably getting a curveball:

| MPH | Zone% | Chase% | SwStr% | CSW% |

| 75.1 | 49.5% | 14.6% | 3.5% | 35.4% |

Results? Batters … SMASH!

| Brl% | BA | xBA | SLG | xSLG | wOBA | xwOBA | K% | BB% |

| 7% | .319 | .372 | .574 | .571 | .380 | .409 | 10.4% | 10.4% |

| 40% | .333 | .348 | 1.333 | 1.146 | .664 | .656 | 16.7% | 0.0% |

*Pitches to RHB – Pitches to LHB

Year of the Juice

So there we have the arsenal and the problems that may lurk within. Fatigue, mechanics, pitch-tipping. None of these are new or unusual problems, and all mostly lie within Kikuchi’s control. But the 27-year-old rookie also has things outside of his control, which are also seemingly pushing on his results from multiple sides.

For one, like all pitchers, Kikuchi is dealing with a baseball whose juiciness is surely beyond argument at this point. Not to mention balls that are slicker, with tighter seams that are harder to grip, negatives compounded by the excessive sweating of Kikuchi, who will sometimes soak through three uniforms in a start. Kikuchi has had so many problems with his grip and keeps such an excessive amount of pine tar on the brim of his cap that accusations of cheating were hurled from all over New York after cameras caught Kikuchi putting his hand to his hat between almost every pitch of a successful start against the Yankees in May.

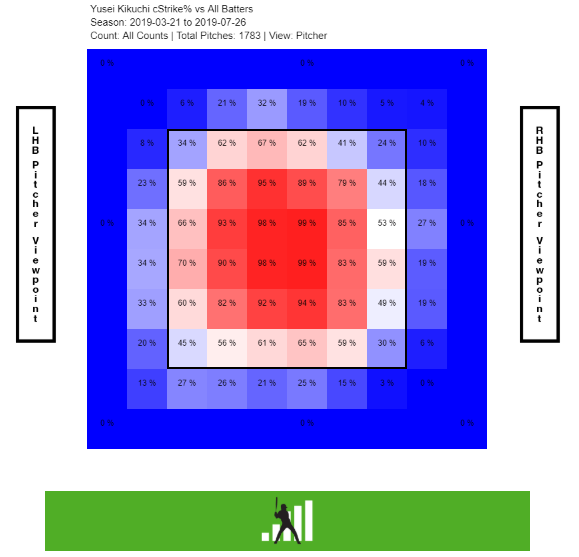

The Incredible Shrinking Zone

Few pitchers have had more strikes stolen from him than Kikuchi. In 2019, batters have taken 316 of Kikuchi’s pitches in the zone, with only 260 of them actually being called strikes. How does Kikuchi’s 82.3% line up with the rest of the league in the department of strike-thievery?

Of 242 pitchers who’ve had a minimum of 100 called strikes, Kikuchi is fourth from last among starting pitchers and is only a half-percent away from last, a place that Kikuchi had occupied until his most recent start.

Here’s what 18% of strikes down the drain look like:

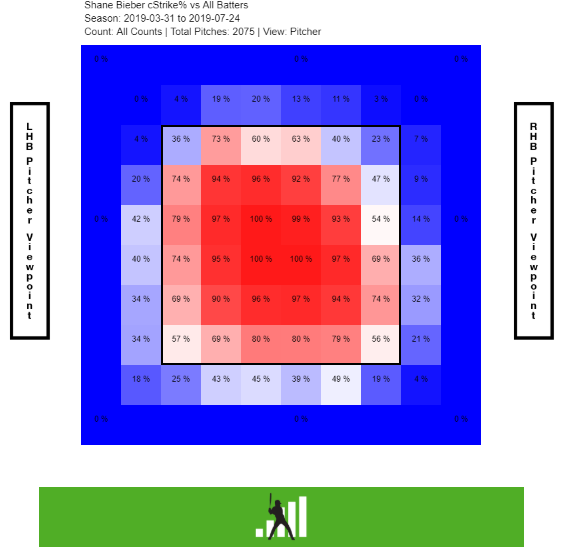

For comparison, here’s a look at Shane Bieber, who leads starting pitchers with 93.9% of his pitches in the zone being called strikes:

I’m sure heat maps like that aren’t frustrating to pitchers at all. Particularly the ring between the outside edge and the heart. Yuck. But we can’t just blame it all on the umpires.

Because we need to talk about Omar Narvaez. Out of 41 catchers who’ve caught at least 300 innings, Narvaez ranks second to last with a – 9.7 frame-rating from Fangraphs.

Open Sesame

After claiming they would essentially use him as an opener every fifth or sixth start, the Mariners have done it exactly once, on April 26. But could Kikuchi be better served by serving as a bulk reliever?

Out of curiosity, how has Kikuchi fared each time through the order this year?

| ERA | xFIP | K% | BB% | WHIP | HR/9 | |

| 1st Time | 4.69 | 5.89 | 15.1% | 12.0% | 1.74 | 2.45 |

| 2nd Time | 4.11 | 4.97 | 14.3% | 4.8% | 1.28 | 1.17 |

| 3rd Time | 7.81 | 4.38 | 22.7% | 5.0% | 1.34 | 1.95 |

This guy couldn’t maybe be helped by coming in later?

Death by a Thousand Cuts

That’s what I think of when I think of Kikuchi’s year so far. Which is why I’m bearish on the rest of this year but bullish for 2020 and beyond. There are just too many factors working against Kikuchi for him to have a sudden turnaround in 2019 because some things just can’t be fixed in two months.

Featured Image by Justin Paradis (@FreshMeatComm on Twitter)

Actually, most guys to come over the MLB to immediately dominate. Even Dice-K did. Its not really a transition like every other one – pitchers seem prepared to compete on day one coming over from Japan and the edge they have due to lack of scouting and looks generally puts them as far ahead as they will ever be. A hitter would have quite the diffefent experience. Unfortunately it probably won’t get much better for him as it usually doesn’t. I am not sure I can think of anyone who improved much after year one of coming over from Japan unless we are going to look at RP.

I that times through the order graphic, the thing that is (always) missing is AB. Is the sample size large enough to be meaningful? There are a lot of good reason that the data for 3rd time through is innacurate – here are a few. 1) pitchers get pulled after bad things happen – your last inning is going to look worse in terms of outcomes for that reason alone. 2) The top of the lineup is way better than the ass-end. You get pulled near the top of the order in all likelihood without getting to face the placeholders at the bottom, which would have evened things out. Openers are overwhelmingly a disaster and don’t really solve problems in most cases. The only team that does it well has their entire staff (predictably) on the DL and the rest of the league just gives away games as they mindlessly deploy the strategy.

1. I don’t think I said that NPB players don’t dominate in their 1st year, just that Kikuchi wasn’t expected to be on the same level as Darvish, Tanaka, etc. And you might not be able to think of people who’ve gotten better after Year 1(even though Darvish did ;) but the point I’m trying to make is that given Kikuchi’s dedication to improvement using modern tools, and given some factors outside of his control(strike-squeezing/Omar Narvaez) I think he’s got a better chance than most of improving in the second year. We’ll see.

2. I’m aware of all the reasons that times through the order doesn’t tell the whole story, but it can tell part of it (incidentally the IP #’s are 40, 46, 28) Honestly, I don’t even care that much about the 3rd-time-through numbers, its the first time through. And 40 innings are enough for me to judge that Kikuchi has been a 1st-time-through disaster. Recommending trying an opener isn’t making a judgment on the strategy as a whole, or about trying to fix Seattle’s problems. Just Kikuchi’s specifically. And if you’re horrible in the first inning AND Seattle has supposedly wanted to limit his innings, then I think using him as a follower is at least worth a shot. It’s about trying to find any and all ways to set your $50 million investment up for success…What, is he going to be worse?