“All relief pitchers are failed starting pitchers” is a common adage used across professional baseball that rings true when looking at the history of nearly any reliever in Major League Baseball today. If they didn’t begin their big league career as a starter, they almost certainly began their minor league career as one before transitioning to the bullpen at some point.

It seems a bit counterintuitive to throw talented pitchers into the bullpen when starters are so much more valuable on a volume basis, but there is logic behind it. For most pitchers, shorter outings lead to significantly improved stuff as a result of not having to pace themselves over 5+ innings each game. In a sense, being a reliever gives you full license to empty the tank every outing.

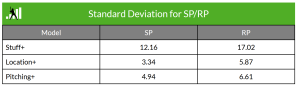

Eno Sarris’ Stuff+ model primer shows us a standard deviation difference of about 5.5 points between a starting pitcher and a reliever. This means that a starting pitcher with a league-average arsenal (100 Stuff+) will theoretically improve to an above-average 105 Stuff+ score if they were to transition to the bullpen and shorten their outings.

In short, relief pitching is almost universally seen as a fallback option for pitchers who just couldn’t cut it as full-workload starters. For most, going to the bullpen as a professional means that is likely where you’ll spend the rest of your career. It is exceedingly difficult to successfully translate back into the starting rotation once your arm, mind, and pitch arsenal have been catered to relief work.

Difficult, but as we are beginning to see more and more in recent seasons, not impossible.

We are in an age where the lines between the bullpen and rotation are more blurred than ever. We still have our conventional starters and relievers, but we are also seeing more ambiguous roles for pitchers on a 26-man roster. We now have openers, multi-inning bulk relievers, and starters with two-pitch arsenals only going 4-5 innings an outing instead of 6-7. As the game has placed a heavy emphasis on velocity and stuff, the distinctions between these two roles are beginning to evaporate.

Just look at everyone’s favorite evil pitching laboratory, the Tampa Bay Rays. For three consecutive seasons, the Rays have converted true one-inning relief arms into full-blown starting pitchers capable of going 5+ innings on any given night. In 2021, it was Drew Rasmussen. In 2022, Jeffrey Springs.

The most recent test subject was 2023 waiver-claim Zack Littell, who was struggling to stick on a major league roster as a reliever at the beginning of the year, and pitching 8-innings of one-run ball against playoff contenders by the end of the season.

How have they done it? What is the common denominator between Rasmussen, Springs, and Littell that made the Rays think they could stretch them out to be effective major league starters?

To put it succinctly, I think there are three major things that indicate a reliever may be able to make it in the starting rotation:

- An uncommonly diverse arsenal of pitches with good stuff and/or unique shapes (or the potential for such an arsenal).

- Above-average command for a reliever.

- Neutral platoon splits that allow the pitcher to get both righties and lefties out consistently.

My theory is that you don’t have to have all three of these qualities to make the transition work, but having at least two of them makes you an intriguing candidate to rediscover your roots as a starting pitcher.

With that, I’m going to apply this general framework to a few major leaguers I’ve identified as good candidates for the next reliever-to-starter experiment. I’ll try to stay away from starting pitching prospects who just came up to help out in the bullpen and relievers who transitioned to the bullpen after starting in the majors as recently as a couple of years ago. We already know those guys can start, let’s find some true relievers to work on.

And no, I haven’t restricted myself to just Rays pitchers.

Andrew Wantz, LAA

Our first guinea pig is reliever Andrew Wantz of the Los Angeles Angels, who debuted in 2021 and has spent parts of the last three seasons pitching exclusively out of the Angels bullpen. The 28-year-old righty has appeared in 90 games in MLB thus far, 86 of them as relief appearances and 4 as opener assignments.

Outside of those three qualities I mentioned, a big feather in Wantz’s cap for a potential transition to the rotation is that he already works multiple innings relatively consistently. He’s never pitched more than 2.1 innings in a major league game, but 3 of his last 4 outings in 2023 lasted 2 innings. That’s not to say I think the Angels are auditioning him for the rotation, but it will take less time and effort for him to get stretched out than a guy who has only ever worked an inning at a time.

Taking a look at Wantz’s pitch arsenal, it’s clear that he’s got the first parameter of our three locked down. He features a four-seam fastball, cutter, slider/sweeper, and changeup. Stuff+ sees three of these four pitches as above-average (fastball, cutter, slider) and rates his slider as his best pitch at 121. Four near-average or better offerings and a great fastball-slider-cutter foundation are about the best groundwork you could ask for this exercise.

One thing I’m looking for in my relievers here is pitches with Stuff+ scores that will remain above average assuming they take a roughly five point hit when converting to a starter. Wantz fares well in that regard, as his fastball, cutter, and slider would all still grade out above average after the starter penalty, as would his overall Stuff+ score.

In fact, Wantz’s hypothetical 107 Stuff+ score as a starter would be the best of any starter the Angels featured in 2023 not named Shohei Ohtani.

| Pitch | Current (2023) Stuff+ | SP Penalty Stuff+ |

|---|---|---|

| Four-seam fastball | 112 | 107 |

| Cutter | 109 | 104 |

| Slider | 121 | 116 |

| Total | 112 | 107 |

So, Wantz has the arsenal to start games. What about his command?

It’s not absolutely necessary for a starter to have top-shelf command in order to be successful (cough 2023 Blake Snell cough), but my goal here is to find guys with the best chance to have success in a major league rotation, and good command gives you a much better shot at navigating through a lineup more than once.

Relievers tend to have poor command compared to starters as it is, so any reliever with an above-average grade by Sarris’ Location+ model likely has pretty great command. Wantz scores a 101 here, making him safely above-average compared to his bullpen contemporaries.

Traditional stats argue this point a bit, as his 9.4% walk rate in 2023 is above the league average of 8.6%. Still, walks don’t necessarily indicate poor command. I would trust a figure like Location+ more when projecting how well he would do as a starter because it calculates on a per-pitch basis instead of a per-AB basis.

Finally, I’ll take a look at Wantz’s platoon splits to see if he fares considerably better against righties than lefties or vice versa. Given the supination-based arsenal he features, I’d expect him to struggle a bit against lefties and fare well against righties.

The only significant difference in usage across the platoon split for Wantz is that he features his changeup more against lefties and leans on his slider more heavily against righties, which makes total sense given conventional wisdom on how to attack right-handed and left-handed batters.

Despite its poor Stuff+ score, that changeup actually kept lefties in check incredibly well in its abbreviated showing last season, registering a 53.3% whiff rate against left-handed hitters. It’s a doozy of a changeup too, featuring almost 13 inches of arm-side break and 2.9 inches of ride, suggesting Wantz kills vertical break on the pitch very well.

Still, this is Wantz’s only true weapon against lefties, as his primary fastball/cutter/slider mix gets punished from that side of the plate. Overall, lefties tallied a .314 wOBA against him compared to just .242 for righties, which isn’t an egregious discrepancy but definitely indicates room for improvement.

One heartening aspect of Wantz’s platoon splits is that he actually punched out lefties more often than he did righties in 2023 (24.2 K% vs. 18.1 K%, respectively) and walked them slightly less often. This is likely the culprit for most ERA estimators actually liking Wantz more against lefties last year, which is a bit tenuous given the relatively small sample and the fact that his K and BB numbers are far more even for his entire career.

Although, the 2023 version of Wantz’s changeup was about a mile per hour harder than his career norm, featured about an inch more horizontal break, and was thrown slightly more often in 2-strike counts. It’s a small development, but one that might actually suggest there is promise for him to develop a consistently successful approach against lefties.

In total, Wantz is about as close to a perfect candidate as you’ll find for a bullpen-to-rotation transition. He’s got the diverse pitch mix, he’s only 28 years old, and he’s already starting to appear in more multi-inning outings lately. If I were to make any changes to his arsenal to push him over the top, I’d likely see if he can add horizontal break to his slider to make it a true sweeper given that he already features a good complementary cutter to go with it.

Some tinkering with the changeup and a more concrete approach against lefties, and I think Wantz could, at the very least, be a serviceable back-of-the-rotation arm for a team that is not particularly replete with reliable starting pitchers right now.

Adrian Morejon, SDP

I’ve written about how much I like Adrian Morejon before, and I just can’t stop coming back to him. He has a gravitational pull and I am firmly in his orbit. He’s just too interesting to not use for this experiment.

Morejon has probably come the closest to being a full-fledged starter out of anyone in this piece, but he has still never thrown more than 4 innings in an MLB game and that particular outing came back in April of 2021 when the Padres were still trying to figure out how they wanted to use him. By now, he’s firmly settled in as a reliever with the occasional 2-3 inning outing or opening assignment while bouncing back and forth between San Diego and AAA El Paso.

He’s a supremely talented pitcher with electric stuff, but he hasn’t truly found himself in the big leagues to this point. He’s only 24 and debuted back in 2019 as a 20-year-old, so there’s absolutely still time for him to carve out an identity for himself. It may take a move to another organization willing to give him a shot in the rotation, but I still have faith it can happen for him.

Morejon is working with a four-seam fastball, slider, curveball, and changeup mix from the left side, with three of those pitches grading out as above average.

Looking at pitch grades, Morejon’s stuff would presumably fare well in a traditional starter’s role, as his three best offerings (fastball, curveball, slider) would remain above average by Stuff+. Unlike Wantz, however, Morejon is working with a significantly skewed pitch distribution. He has relied very heavily on his fastball the past two seasons, tossing it 69% of the time in 2022 and 61% of the time in 2023.

It’s easy to see why he might feel more comfortable attacking hitters with the heater. It features over 17 inches of ride with only around 4 inches of arm-side run and was coming in at around 97 MPH in 2022. Morejon’s 2023 was a bit of a lost season as he was just returning from an elbow injury before suffering a knee sprain that halted his momentum in mid-July, so his ~2 MPH drop in fastball velocity this year was likely a consequence of that.

With a full offseason of rest and preparation, I don’t see why he can’t get the heater back up to 96+, especially given how young he is and how little mileage he has on his arm.

| Pitch | Current (2023) Stuff+ | SP Penalty Stuff+ |

|---|---|---|

| Four-seam Fastball | 117 | 112 |

| Slider | 108 | 103 |

| Curveball | 107 | 102 |

| Total | 111 | 106 |

Command-wise, Morejon was… a bit shaky last year, to put it lightly. His 94 Location+ in 2023 suggests that his command was right in line with most relievers: not good! Some context is necessary to fully grasp his situation, however.

Just like his fastball velocity, Morejon’s wandering command may have been a result of the duo of injuries he was dealing with in 2023. His career Location+ number prior to 2023 was a much nicer-looking 102, suggesting he was never really able to settle in at any point last season. Conventional analysis backs this sentiment up, as his walk rate shot up to 11.4% after cruising at a sparkling 6.4% in his big league career from 2019-2022.

While Morejon’s arsenal and command require a bit of faith that he’ll return to his 2022 form in order to fully buy in, his platoon numbers are pretty self-explanatory.

Morejon is interesting in that he likes to mix up which of his breaking balls he tends to lean on depending on the handedness of the batter. He tosses the curveball primarily against righties and the slider against lefties, and he effectively ditches the curveball altogether against lefties. Either way, his approach is still very fastball-dominant, but he throws it particularly often against lefties and it’s not hard to see why. Let’s look at the platoon numbers on Morejon’s four-seamer from 2022, the last season in which we have a good sample of his better heater.

| Metric | vs. RHB | vs. LHB |

|---|---|---|

| Whiff% | 18.9 | 29.8 |

| Groundball% | 27.3 | 38.1 |

| CSW% | 20.7 | 36.3 |

| HardHit% | 43.6 | 25.0 |

Assuming he gets back to the 2022 version of his fastball, Morejon might be able to just keep doing what he’s been doing against lefties: being relentlessly aggressive with heaters in the zone and putting hitters away with the slider.

Righties pose an interesting challenge for Morejon because he really doesn’t have a good pitch that leverages arm-side break to keep hitters from zeroing in on pitches on the inner half of the plate. He has that changeup, but it doesn’t grade out well and he effectively stopped throwing it with any frequency after 2021, when righties mashed the pitch over the course of the season.

This does not mean Morejon has no chance of getting right-handed batters out consistently, he just has to be a little more creative than, say, Shane McClanahan, who has a left-handed changeup gifted to him by the heavens. Plenty of successful lefty starters have managed without a pitch that breaks to the arm side. Justin Steele just had a Cy Young-caliber season in 2023 while relying almost exclusively on a fastball/slider mix.

Heck, Morejon’s former teammate Blake Snell is actually about the best big-league comp you could ask for. They both feature the exact same pitch mix (fastball, slider, curveball, changeup), all with reasonably similar shapes and velocities. It even looks like Morejon may have been taking cues from Snell and trying to replicate his changeup, as the pitch began to resemble Snell’s version much more closely in 2023.

| Pitch Spec | Morejon CH (2023) | Snell CH (2023) |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity (MPH) | 88.7 (+4.4) | 86.8 |

| Vertical Movement (In) | 11.7 (+5.0) | 11.0 |

| Horizontal Movement (In) | 11.6 (+3.4) | 12.8 |

| Horizontal Approach Angle (Degrees) | -0.17 (+0.33) | -0.08 |

Morejon started throwing the changeup over 4 MPH harder, added a significant amount of movement on both planes and ever-so-slightly raised his release point. I can’t say for sure if he was trying to emulate his teammate here, but this change sure seems intentional. Regardless, shaping your pitches to be more like 2023 Blake Snell is a fine goal by my estimation given what we know about the filthy stuff Snell possessed last season.

The two pitches performed much differently in 2023, but I think it’s all about finding the right pocket for Morejon. He’s a 24-year-old who was thrust onto the big-league roster when he was 20 and has been fighting an uphill battle ever since. I would love to see what he could do if he really had a clean slate of health and maybe a fresh start with a new team. The talent is there and I think he’s inching closer to finding a repertoire that works for him.

Even after a rough 2023, I am still fully on board the Morejon starting pitcher train. I just can’t quit him.

Shawn Armstrong, TBR

Well, I had to fit a Rays guy in here eventually, right?

Shawn Armstrong is an interesting case among the pitchers I’m writing about here. He’s the oldest on the list and he’s been a full-time reliever longer than anyone on the list as well. Armstrong debuted out of the Cleveland bullpen back in 2015 and didn’t start a single game for his entire career until, you guessed it, the Rays got their hands on him.

His first career start didn’t come until his 193rd career major league game in August of 2022. Since being acquired by Tampa Bay, he’s still been used as a one to two inning guy either out of the bullpen or in an opener role.

Armstrong is coming off a career year in 2023, posting a sparkling 1.38 ERA over 52 innings to go along with a career-best 5.3% walk rate and a healthy 26.1% K rate. How he managed to do this as a 33-year-old is what makes him such an interesting pick to potentially be converted into a starter, especially when looking through his pitch arsenal.

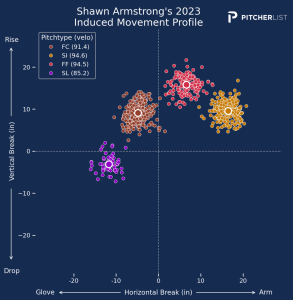

While more and more pitchers are relying heavily on their secondaries and offspeed stuff to get by these days, Armstrong represented a bit of a rebellion against this idea. He dominated hitters by pounding the zone with three different kinds of fastballs: a four-seamer, a cutter, and a sinker. His only breaking or offspeed offering was a slider that he only threw 7% of the time.

All three of these fastballs were flat-out electric in 2023. Armstrong found a way to feature an arsenal that consisted of 93% fastball variants with less than 4 MPH difference between them and still put up one of the best seasons of any reliever last year. Just look at some of the results of this arsenal.

Now, I understand that an arsenal comprised of three fastballs and an oft-used slider might not strike you as particularly diverse, but I think there is more going on here in how these pitches interact that makes the arsenal feel diverse when you’re the one trying to hit it. The foundational idea is to have three fastballs with a very tight velocity distribution that break three different directions: the four-seamer stays relatively true, the cutter breaks glove-side, and the sinker breaks arm-side.

This is just a beautiful induced movement profile, one that thoroughly covers the horizontal plane and features the occasional option to leverage the vertical plane a bit more in the slider.

Speaking of, Armstrong used to throw that slider more but recently traded some usage in favor of the cutter. A similar adjustment worked absolute wonders for teammate Robert Stephenson when he was acquired by the Rays in the middle of last season. While the two cutters these pitchers throw are significantly different in terms of sheer movement, it’s clear that the Rays have been encouraging some of their arms to try throwing firmer and tighter breaking balls lately.

So, while this arsenal can be boiled down to “a few different fastballs and a slider”, it plays much more like a starter’s arsenal when breaking down which strike zone planes it can leverage and how adaptable it can be in response to different batters.

None of these pitches blow Stuff+ out of the water, but all four of them sit right in that comfortable above-average zone. With the starter penalty taken into account, it would likely grade out as a roughly average arsenal across the board.

Still, I think Armstrong’s success comes more from the interactions between his pitches as opposed to the raw stuff he features. Were he to convert to a starter, he would have a good number of options for how he could sustain success multiple times through the order.

What instills even more faith in Armstrong is his great command. He registered a 108 Location+ score and 7.9 BB% in 2023. That Location+ number is right up there with Rays starters Zach Eflin (108), Aaron Civale (106), and the most recent starter conversion himself, Zack Littell (105). Great command combined with a unique pitch repertoire with the potential to manipulate shapes on the fly is exactly the kind of pitcher I’m looking for as a potential bullpen escapee.

Because the Rays seem to making it an annual tradition to take a random bullpen arm nobody thought would start and stretch them out into a dependable rotation piece, I don’t see why Armstrong can’t be the next in line for that treatment. Typically, the way they’ve stretched their guys out has been to give them a few 1-2 inning opener assignments, then slowly loosen the leash on them in these outings until they can throw 3-4 innings regularly.

From there, they shoot for 5-ish innings per outing on a regular basis. When the pitcher can then handle 5 innings, they let them off the leash and allow them to assume the traditional starter role. Armstrong already had several opener outings last year that lasted multiple innings, including a 3-inning outing against the Phillies on July 6th. This might indicate that they have already put him on track to break into the rotation if the need arises at some point in 2024, and given the issues the Rays have encountered with pitching injuries over the last few seasons, that’s not unlikely.

Caleb Ferguson, LAD

So we go from a guy who pretty much knew from day 1 of his major league career that he was a reliever in Shawn Armstrong to a guy who actually had some prospect hype surrounding him as a potential starter at the time of his debut.

Caleb Ferguson never ascended past the #16 spot on the Dodger’s top prospects list before making his debut on June 6th, 2018, but there was reason for optimism that he could carve out a role as a solid big league starting pitcher. Ferguson was drafted in 2014 and put himself on the map with a stellar 2017 season at High-A Rancho Cucamonga, earning himself a call-up to the Dodgers less than a year later as a 21-year-old.

He started his first three MLB appearances, going 1.2 innings on June 6th against the Pirates, 4 innings on June 12th against the Rangers, and 5 innings on June 17th against the Giants. This, however, was the point where his role on the pitching staff started to shift. He made 26 more appearances in 2018, all of them out of the bullpen and none lasting more than 4 innings. He’s served as an opener a few times since then, but the last time he tossed more than 3 innings in a big league game was his 4th career outing in that 2018 season.

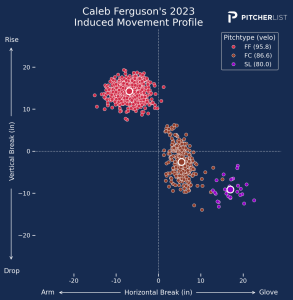

Ferguson, much like Armstrong, is a very fastball-dependant pitcher. He throws a four-seamer and a cutter that makeup 96% of his arsenal, with the other 4% being comprised of a sweeper and the elusive curveball.

This is an interesting arsenal for a multitude of reasons. The first thing to note is that he doesn’t feature any pitches that break significantly to the arm side, like some of the lefties I mentioned earlier. Ferguson also features some pretty unique pitch shapes here. His four-seamer doesn’t look too overpowering with just 15 inches of ride at 95 MPH, but it registered an above-average 26.1% whiff rate and 108 Stuff+.

His cutter is a bit of an anomaly, as it features the third-most glove-side break and second-most drop of any lefty cutter in the league. This makes it more of a true breaking ball or gyro slider in effect, but he gets it up there at almost 90 MPH from time to time. It also grades out well with a 108 Stuff+, but the results on the pitch are closer to average.

His sweeper is also slightly anomalous, coming in at 80 MPH with an above-average horizontal break and the third-most drop of any lefty sweeper. All of these movement profiles tell me Ferguson is a big supination-biased pitcher who loves to spin the ball instead of getting behind it and carrying it.

The arsenal would work as a starting pitcher from a stuff perspective, and Ferguson gets bonus points for having unique shapes on his three primary pitches.

His command is solid as well according to Location+, which gives him a score of 101. His major league walk rate has tended to fluctuate quite a bit in the past, but the 8.5% it settled at in 2023 seems like a better reflection of his true command than the ugly 13.2% and 12.0% walk rates he posted in 2019 and 2022, respectively.

The main concern on my end with Ferguson going into this experiment was how he would manage to get righties out consistently with an arsenal so heavy on glove-side break and without an exemplary fastball to elevate against them. Turns out, he’s got a pretty interesting platoon split going on.

So, to get this straight, he got better results against righties despite walking them more and striking them out less, allowing more hard contact, but also getting more whiffs with that weird cutter against them. This was a bit perplexing to look at initially, but given that the cutter performed significantly better against righties and he also counterintuitively used the sweeper exclusively against righties, I think the key might be that right-handed batters have a hard time handling the vertical plane against him.

He has two pitches that break glove-side, one that breaks almost 17 inches and one that breaks about 6 inches. These two pitches also feature different amounts of drop, with the cutter dropping about an inch and the sweeper dropping almost 7. Couple that with a fastball that gets slightly above-average ride and the fact that the cutter has a huge bandwidth for how much it drops, and you’re looking at a guy who pretty much covers both extremes of the vertical axis and everything in between.

Guys with cutters like this tend to be great at manipulating shape and keeping hitters guessing as to which variant they’re getting on any given pitch, which works wonders navigating through lineups multiple times. This also partially explains why righties whiffed on the cutter so frequently; they were either getting a virtual fastball with more ride or a near sweeper with higher velocity.

I can’t be too sure due to this being such an odd arsenal, but I have a feeling this would allow Ferguson to be relatively successful were he tasked with getting through a lineup 2 or 3 times. I would try increasing his sweeper usage against lefties to get them off the cutter (lefties absolutely mashed his cutter in 2023) and changing the shape of the cutters he did throw to left-handed batters.

His cutters to lefties tended to be slightly more vertical with less drop (closer to his four-seam shape), which may have allowed them to zero in on that particular shape and drive the ball with authority on a regular basis.

Some tinkering would be necessary, but I like Ferguson as a guy with solid command, a unique arsenal, and prior experience pitching three to five innings in both relief and starting roles.

Robert Suarez, SDP

Of all the choices on this list, this one might be the one that strikes you as the strangest based on gut reaction. Most of the guys I’ve talked about have been what you would normally call a “middle reliever” or long reliever whose main job is to eat up the middle innings of a game and bridge the gap to the back end of the bullpen.

Robert Suarez, however, is the back end of the bullpen. None of the pitchers I’ve written about so far have had significant experience being setup men for closers, let alone being closers themselves. Suarez was a key piece at the back of the Padres bullpen in 2022 and was trusted with some extremely high-leverage situations in the postseason. He picked up 11 holds and one save in 2022 to go along with a 20.9 K-BB% and 3.22 FIP.

2023 was a step back for Suarez, as he battled an elbow injury early in the year followed by a 10-game suspension for having a foreign substance on his arm during a game in September. His results were not nearly as impressive in the 27.2 innings he managed, registering 8 holds and no saves with a 13.0 K-BB% and 4.48 FIP.

Despite the rocky 2023, I still very much believe in Suarez as a potential option to lengthen out into a starter. A big contributor to that belief is that he has easily the most diverse arsenal of anyone I’ve talked about so far. Suarez operates with a four-seamer, sinker, changeup, slider, and cutter. That’s 5 unique pitches.

He doesn’t just feature 5 different pitches, he throws 5 different pitches that all rate very well by Stuff+.

Arguably his defining feature is his array of blazing fastballs, as all three of the heater variants he throws eclipsed 93 MPH in 2022. The cutter velocity dropped off to around 90 in 2023, but his four-seamer remained steady and his sinker actually gained velocity, so it may have been more of a shape-tinkering thing than an injury thing.

His secondaries jump off the page as well. From 2022 to 2023, Suarez seemed to ditch the curveball for a very tight, very gyro slider at 86 MPH, 2.2 inches of ride, and 3.8 inches of glove-side break.

Then, we have the moneymaker. Suarez’s changeup is absolutely one of the filthiest thrown by a relief pitcher. It features over 2 more inches of arm-side break than the average right-handed changeup and comes in almost 3 MPH harder than average. Even in a down year, the changeup recorded an above-average whiff rate, .151 wOBA (.294 is average!), and .136 ISO.

Gross!

And that’s not all Suarez brings to the table. He also actually posted an exemplary 105 Location+ score in 2023, which is higher than any starter the Padres deployed over the course of the season. Keep in mind, Location+ isn’t as sticky season-to-season as Stuff+ is, but it’s still a good measure of how well a pitcher is capable of commanding his arsenal.

He has posted walk rates of 11.0% and 9.3% in his 2022 and 2023 seasons, respectively, which isn’t anything special but remains reasonable given his Location+ score.

Looking at platoon splits, it’s clear what his approach is against lefties. He attacks them with a steady diet of four-seamers and changeups, and why not? Those are two of his best options against opposite-handed hitters, so he has very little incentive to go to anything else, especially considering how good his changeup is.

Righties present an interesting dilemma that I’m not sure Suarez has totally figured out yet. Between 2022 and 2023, his approach against righties has changed a bit.

In 2022, he relied primarily on the four-seamer while occasionally going to the sinker, changeup, and cutter. In 2023, he essentially ditched the cutter, split his usage almost evenly between the four-seamer and sinker, and ramped up the changeup usage.

The downturn in velocity combined with the fact that righties mashed the cutter to the tune of a .273 ISO and .341 wOBA in 2022 provides a pretty clear rationale behind his decision to scrap it against them. The other adjustments are a bit more interesting.

His four-seamer registered a 25.8% whiff rate and .295 wOBA, but the sinker was absolutely confounding righties in 2022. Trading in some four-seam usage for greater emphasis on the sinker may have led to the reduced K% in 2023, but it also led to an improved overall performance against them from 2022. His changeup was also dominating righties that year, but the increased usage of it in 2023 led to a noticeable decrease in effectiveness. That may just be symptomatic of the pitch being a little overexposed, especially considering Suarez’s relative lack of glove-side options.

In all, Suarez stands out because of his combination of raw stuff, good command for a reliever, and wide breadth of pitches. Based on those parameters alone, he is exactly the kind of arm I’m looking for. Seeing a former back-end reliever turn into a starter would be a bit odd, but he has all the tools to make it work despite his age and perceived injury risk.

Honorable Mentions

I had a whole list of more than 10 pitchers I wanted to write about here, but I picked out 5 of my favorites to actually go in-depth about. I didn’t want to leave out all of the other arms I thought were interesting, so here’s a quick write-up of my three favorite near-misses and why I think they could work as starters in a nutshell.

Mason Thompson, WSH

Sinker/slider guy with experience going multiple innings out of the pen and five different pitches. Four of those five pitches grade out as above-average by Stuff+, and three of the five would remain above-average after the starter penalty. 97 Location+ is rough, but the array of pitches and the gyro slider that carved up lefties in 2023 instill faith that he could succeed in a starter role.

Julian Merryweather, CHC

I’ll be honest, one of the main reasons I didn’t include Merryweather is because his injury risk is already incredibly high as a reliever, it would be through the roof with an increased innings load. Still, the fastball/slider/changeup core gives him weapons against righties and lefties, and he controls them well. Good stuff too.

Bryan Baker, BAL

Great cut-ride fastball with an elite slider and a changeup that performed well against lefties each of the last two seasons. All three pitches would be above average after the starter penalty, and the 99 Location+ is enough to believe his command wouldn’t be prohibitively bad.

Photos by Matthew Pearce/Icon Sportswire and Alice Butenko/Unsplash | Featured Image by Ethan Kaplan (@DJFreddie10 on Twitter and @EthanMKaplanImages on Instagram)