The 2021 season will be an important one for Mariners pitcher Justus Sheffield. It will, hopefully, be the first full season for the 24-year-old, who has, like a lot of other young pitchers, experienced his fair share of ups and downs thus far in his young Major League career. He’s thrown just 94 innings so far, and his career 4.50 ERA doesn’t jump off the page, but that doesn’t mean that is who he will be going forward.

2020 was quite a successful season for the young pitcher. He got off to a slow start in 2020, with eight earned runs allowed in his first two starts of the year, but he recovered quite nicely to finish the season with a 3.58 ERA, and even more encouraging, a 3.17 FIP in 55.1 innings pitched.

That is especially important when remembering Sheffield’s first extended action in 2019 in which he posted a 5.50 ERA. While the 2019 version was maybe more exciting due to more whiffs and strikeouts than in the 2020 version, he was very inefficient on the mound. He made it through six innings just once in 2019, and he labored through the majority of his starts. A major reason for that can perhaps be because he struggled with his control and getting pitches over the plate. His walk rate was 10.7%, and despite a more-than-respectable 22% strikeout rate, a lot of the upside of that strikeout was negated, as he ended up with just a K-BB% rate of just 11.3%. Furthermore, Sheffield averaged around four pitches per plate appearance in 2020, above the league-average.

So, while Sheffield showed some upside in terms of strikeouts and whiffs, he still struggled overall due to issues with his command. If he kept up on that trajectory, he would likely continue to struggle to get through six or more innings, and maybe not end up as a long-term starting pitcher. To keep his spot in the rotation and take the next steps forward in his career, he would need to adapt and change his game a bit to have a shot.

Better Stuff

The biggest change that Sheffield made was in his repertoire, as he ditched his four-seam fastball for a sinker, a change that was evident going back to the original spring training back in March. It goes against modern pitching conventions, as it is a bit of a zig-where-others-zag move; not many pitchers are moving away from four-seamers and turning to sinkers as frequently in this age where velocity and strikeouts are valued more than ever. However, there was a reason for him to change gears in this department, as his overall repertoire just was not working effectively in 2019, with the biggest culprit being his four-seamer.

In 2019, his four-seamer was frankly quite bad. The pitch had a zone rate of just 51.86%, which is worse than the league-average. Hitters could lay off the pitch, but even when they did swing, they did damage, as his fastball got crushed to a tune of a .507 slugging percentage. That was mostly due to the pitch just being relatively flat, with not much movement and some of the worst vertical movement and spin—or lack thereof—of any four-seamer in baseball. That led to just a 12.8% whiff rate, among the lowest in baseball. All of those factors combined led to Sheffield’s four-seamer accumulating a pVAL of -3.5 despite throwing just 36 innings.

Shifting to the sinker hasn’t alleviated all of his prior problems on its own though. While it was better than the four-seamer with a pVAL of 0.9, it’s still not the best sinker in the league, or anything close to it. The pitch did have a 13.8% whiff rate in 2020, which is higher than the whiff rate of his four-seamer in 2019, but overall, the pitch didn’t do him many favors in terms of overall strikeout rate. However, it is important to note that he was better able to command the sinker, with a zone-rate of 53.9%, which helped drive his overall zone-rate to an even 50% in 2020, a rate that is better than league average. Not only that but as compared to his four-seamer from 2019, hitters were not able to get such strong results on the new sinker:

| Pitch | Usage % | Zone % | AVG EV | SLG | xSLG | wOBA | xwOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 FF | 47.8 | 51.9 | 91.4 | 0.507 | 0.460 | 0.395 | 0.377 |

| 2020 SI | 47.4 | 53.5 | 89.8 | 0.359 | 0.416 | 0.341 | 0.353 |

Based on results alone, this looks like a positive change for Sheffield. The pitch also lived up to its sinker name and generated ground balls at a 53.2% rate, and hitters weren’t able to make much noise when putting the ball in play.

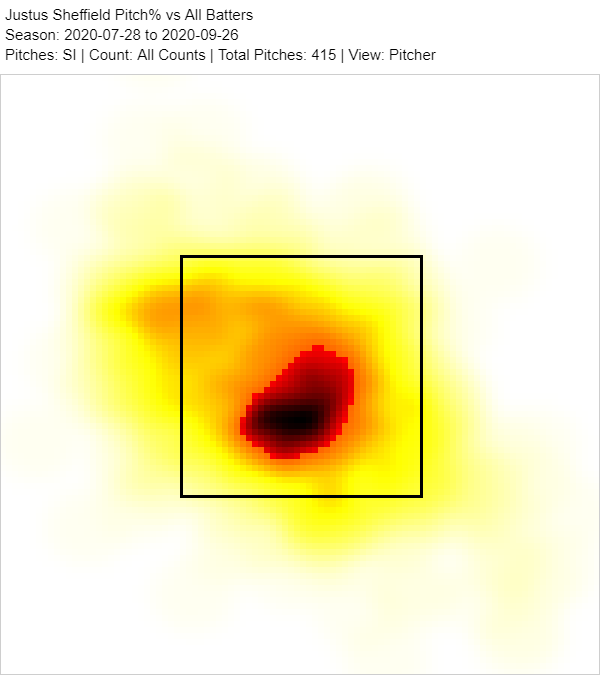

It also appears that shifting to the sinker impacted his other pitches; his slider and changeup. The best way to show this is to take a look at the individual heatmaps for his three pitches in 2020:

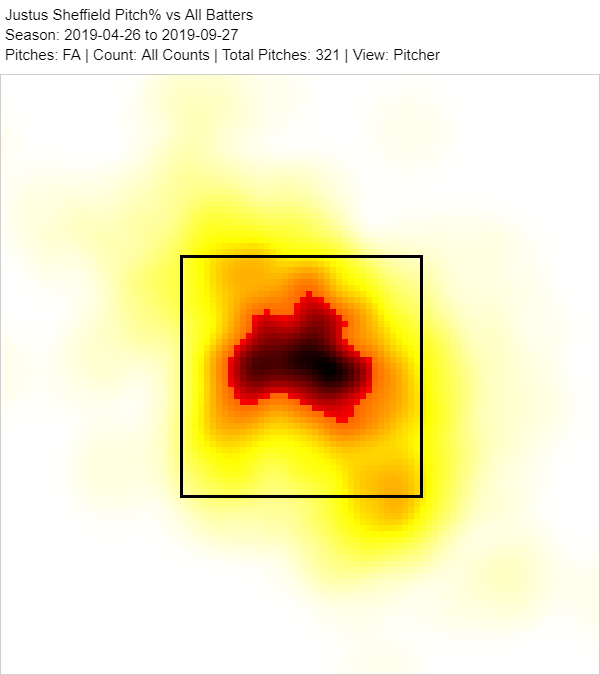

From this, it looks like Sheffield’s pitches were more likely to end up towards the bottom of the zone. Keep that in mind for a little bit later, but now compare his sinker heatmap to his four-seamer heatmap from 2019:

It looks like that in 2019, Sheffield was pitching more to the modern pitching strategy of trying to locate fastballs up in the strike zone. That is usually a good idea, and there is a reason why it is one of the biggest trends in pitching right now. However, it maybe isn’t the best idea considering that first, his average fastball velocity in 2019 was just shy of 93 miles-per-hour, but second, that the pitch was, as mentioned earlier, quite flat. A pitcher may be able to get away with a flat fastball up in the zone with higher velocity, or with the opposite; better movement and less velocity, but not likely both, and unfortunately, Sheffield had both of those things working against him in 2019, and the pitch got rightfully got hit hard.

So, the sinker would, in both name and practice, wind up lower in the zone than a traditional four-seamer. But how would that help his other pitches play up? Recall the heatmap loop from earlier, and that now all three of Sheffield’s pitches were generally located in the lower portion of the zone. What he was able to accomplish by doing this is bombarding hitters with a medley of pitches in the same general area of the plate differing in both speed and movement. This looked to be the ticket for Sheffield in 2020, as his slider and changeup graded out well in terms of pVAL; especially so his slider, which clocked in at a 4.5 value, ranking 15th among starting pitchers and a huge shift from the -3.8 mark he posted in 2019.

In essence, it looks like the lower in the zone sinkers at an average of 92 miles-per-hour have made his sliders, which clocked in at around 82 miles-per-hour on average, look more tempting, and at times, left hitters looking quite foolish:

While the slider wasn’t the best out there in terms of whiffs, he still got very favorable results when the ball was put in play. It was a recurring theme for Sheffield in 2020 to get favorable results when the ball was put in play, even when one look at his profile shows that he had an extremely high hard-hit rate, which doesn’t fully add up and is worthy of a closer look.

The Hard-Hit Paradox

What is going on with Sheffield’s hard-hit rate is probably the most interesting thing about his season. As mentioned earlier, his hard-hit rate was extremely high, at 46.6%, which was among the worst in baseball. His sinker on its own had a 49.4% hard-hit rate, but yet, when factored into Baseball Savant’s expected statistics, he actually is viewed rather favorably, with xwOBA and xSLG marks that are significantly better than league-average, and much better than in 2019. Another added curiosity is that his barrels per batted ball event rate was just 3.7%, one of the five lowest in the game:

| Player | Hard-Hit % | Barrel/BBE % |

|---|---|---|

| Hyun Jin Ryu | 29.2 | 3.2 |

| Max Fried | 23.8 | 3.3 |

| Brad Keller | 39.1 | 3.7 |

| Sonny Gray | 32.6 | 3.7 |

| Justus Sheffield | 46.6 | 3.7 |

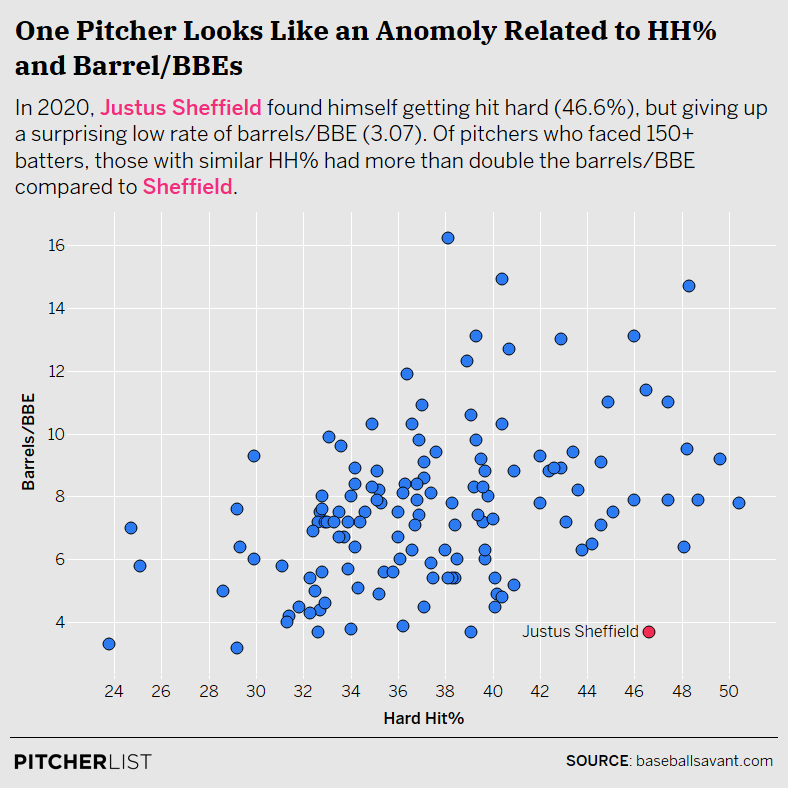

His high hard-hit rate just doesn’t seem right compared to the other pitchers with super-low barrel rates. It especially looks off when plotted alongside the rest of the league:

Data Visualization by @Kollauf on Twitter

While there are other pitchers in a similar vein to Sheffield, in that they have a high hard-hit rate but a lower barrel rate, none of them were quite as extreme outliers. Why might this be the case?

Well, it is important to remember exactly what it is that we’re defining when we say “hard-hit”, and “barrel”. This is likely a refresher for most, but worth reiterating. A hard-hit ball is simply just a ball hit 95 miles-per-hour or more. The definition of a barrel is a bit more fluid, but to keep it simple, a barrel must be at least 98 miles-per-hour and in a range of launch angles somewhere around eight and 50 degrees, depending on just how hard the ball is hit. So, a hard-hit ball is not always a barrel, but a barrel is always a hard-hit ball, and generally, barrels are a better indicator of success—for batters—than the standard hard-hit rate. It makes sense because there’s more context with a barrel, especially because hitters should be striving to hit the majority of their batted-balls in that range anyway, and doing so while hitting balls hard.

So how does this relate to Sheffield? Well, it can be theorized then that despite the super-high hard-hit rate, a good amount of those hard-hit balls could have been hit on the ground. It turns out that was completely the case, and when his hard-hit balls are broken out by batted-ball type, it’s pretty clear:

| Total HH | HH GB | HH LD | HH FB | HH GB % | HH FB+LD % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justus Sheffield | 75 | 38 | 26 | 11 | 50.7% | 49.3% |

Sheffield allowed more hard-hit grounders in 2020 than he did hard-hit fly balls and line drives combined. As a matter of fact, his 38 hard-hit grounders allowed were the eighth-most allowed of the 96 pitchers that threw at least 750 pitches in 2020. To even the playing field, looking at all of the 96 pitchers of this dataset and their rates of hard-hit ground balls, Sheffield is still inside the top-ten:

| Player | BF | HH GB | Total HH | HH GB% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brett Anderson | 202 | 41 | 75 | 54.7% |

| Randy Dobnak | 200 | 34 | 63 | 54.0% |

| Lance McCullers Jr. | 227 | 27 | 51 | 52.9% |

| Max Fried | 224 | 19 | 36 | 52.8% |

| Brady Singer | 263 | 37 | 71 | 52.1% |

| Sean Manaea | 222 | 39 | 75 | 52.0% |

| Framber Valdez | 288 | 48 | 93 | 51.6% |

| Brad Keller | 215 | 32 | 63 | 50.8% |

| Justus Sheffield | 232 | 38 | 75 | 50.7% |

| Adrian Houser | 246 | 28 | 58 | 48.3% |

It is perhaps also worth giving some credit here to the Mariners team defense, which surely played a role in limiting the collateral damage that Sheffield did when allowing hard-hit batted balls at such a high rate. The Mariners as a team ranked inside the top-ten in both the Defensive Runs Saved and Ultimate Zone Rating leaderboards in 2020. Just for fun, when looking at the pitchers with the lowest wOBA allowed on contact, there are quite a few Mariners pitchers towards the top of that leaderboard:

| Player | wOBACON | wOBACON Rank (out of 96) | xwOBACON |

|---|---|---|---|

| Justus Sheffield | 0.305 | 9 | 0.338 |

| Justin Dunn | 0.313 | 15 | 0.378 |

| Taijuan Walker | 0.318 | 18 | 0.377 |

| Marco Gonzales | 0.319 | 20 | 0.361 |

| Yusei Kikuchi | 0.341 | 43 | 0.317 |

This on its own isn’t perfect, as Walker pitched just 27 innings for the Mariners last season before being moved to the Blue Jays at the deadline, and Kikuchi is the exception in that his wOBA on contact is worse than his expected one; but overall, the Mariners pitchers that qualify for this dataset not only appear in the top half of the leaderboard but some close to the very top. While Kikuchi and Gonzales make sense along with Sheffield as primary ground-ball pitchers, it also should perhaps be partially viewed as a testament to the sound defense that was on display by Seattle in 2020.

Red Flags

That’s not to say that Sheffield is going to continue to maintain this in the future, or that he should be projected to have a similar season in 2021. These all appear to be positive steps forward but it is still important to look at some things that may still be an issue for him in the future. While throwing more pitches in the zone is helping him with his previous command issues, it should also lead to more contact, as it did from 2019 to 2020. While the contact he has allowed has mostly been ground balls, and should still be the case in the future, he is still subject to all of the BABIP-related issues that come with being a ground ball-heavy pitcher, even with what should be a strong Mariners defense behind him and should be kept in mind going forward.

There are other things about Sheffield’s profile that should still raise an eyebrow though. His high hard-hit rate is the most obvious one. He was able to work around it in 2020 with a different repertoire and overall better stuff, but if his profile were to shift back to one more in line with his 2019 season instead, he could be in trouble.

However, the biggest thing to keep in mind when evaluating Sheffield for 2020 is the lack of home runs that he allowed in 2020. It doesn’t matter how many ground balls a pitcher allows, it is pretty difficult for a pitcher to maintain a 4.4% HR/FB rate, which was what his rate was last season, and was one of the lowest in the game:

| Player | HR/FB % |

|---|---|

| Justus Sheffield | 4.4 |

| Spencer Turnbull | 4.5 |

| Dallas Keuchel | 4.7 |

| Max Fried | 4.9 |

| Brad Keller | 5.1 |

2020 did a lot of weird things to player stats, and this is just another one. Among the other pitchers listed here, some further explanation is required. Let’s use Keuchel as an example, as he is a pitcher who may be expected to have a low HR/FB rate due to a weak contact profile based around ground balls. Keuchel’s previous career-best for HR/FB in a single season is double what it was in 2020, so that shouldn’t exactly be expected to stick either. The point is it’s essentially a given that Sheffield will regress in this department in 2021.

That said, remember the other key points. Sheffield featured a different pitch mix that has him locating more pitches in the lower part of the zone, which are theoretically harder to drive over the fence, as well as a lower rate of hard-hit fly balls and line-drives than the average pitcher. The pitch that hitters had the most success in 2019—his four-seamer—is no longer a part of his repertoire, and in his short career, he hasn’t allowed much hard-contact on non-fastballs, with just a .282 wOBA allowed on non-fastballs in 2019 and 2020 combined. A 4.4 HR/FB% is going to be unsustainable, so regression should be expected from Sheffield in the future, but perhaps not to such an extreme opposite.

Conclusion

Sheffield is still ultimately not a finished product on the mound and does still have things that would be in his favor to improve upon. He’s not a perfect pitcher, but compared to 2019, the 2020 edition of Sheffield was a much-improved one, that saw him take a step forward after a rocky debut for the Mariners the season prior. He addressed his biggest weaknesses, and ultimately became a more complete pitcher. It is kind of cliche to say among player evaluators that a pitcher might be, “more of a thrower than a pitcher.” This is generally said to show a pitcher negatively, and the case could have been made for Sheffield to fall into that category based on his 2019. Well, by mixing up his repertoire and going to a sinker that helped his secondary pitches play up, he, in turn, became an overall better pitcher.

He is still a little rough in some other areas though. The hard-hit issues, which did not affect him much last season, could still rear its ugly head in the future. We shouldn’t look at Sheffield’s 3.58 ERA and 3.17 FIP and believe that is who he is going to be going forward. However, the 2020 season was a positive step forward for him, and enjoying this successful run likely did wonders for his confidence, and he has plenty of momentum going forward into 2021.

It is worth noting that the Mariners hope to start the 2021 season with a six-man rotation, which could muddy things up for Sheffield; but he should still be a solid and perhaps underrated sleeper pick for fantasy purposes. Especially when considering his current average draft positions in early NFBC drafts at around pick 298, he could a nice option for many fantasy managers in 2021.

Photo by Kiyoshi Mio/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Jacob Roy (@jmrgraphics3 on IG)