Kenley Jansen knows how to pitch. He’s been very good at pitching for a very long time, despite famously not needing to do it for very long to become very good at it. Even if he’s clearly past his peak, he’s still very good by most standards. Part of why he’s worth writing about now is the bounce-back campaign he seems to be having after a few years of diminishing performance.

When I say he’s learning how to pitch, I don’t mean it as an insult. It’s how I refer to the phenomenon of a once-dominant pitching talent who manages to reinvent themself once the physical gifts bestowed upon them in their youth begin to fade.

As this happens, there usually comes a point at which a pitcher either makes the adjustment, they don’t. It can be the difference between a Hall of Fame career and merely a Very Good one that peters out just a little too early. That kind of natural evolution is learning how to pitch.

It means Bartolo Colon learning how to dot his two-seamer so well that it didn’t matter that it was in the mid-eighties and he threw it 80% of the time. It’s Zack Greinke refining his command and taking his arsenal seven-deep after losing the meager velocity he had. It was C.C. Sabathia tacking on an extra 10 WAR at the end of his career by flipping 88 MPH cutters around the edges. Clayton Kershaw throws sliders half the time now. Even Mark Buehrle concluding his time in the majors in 2015 with a .316 wOBA on a four-seamer that barely broke 84 MPH.

Those are generally exceptions, though. Baseball history is filled with All-Star talents who faded away along with their stuff. Neither Jered Weaver nor Tim Lincecum was long for the league once injuries sapped their form. Félix Hernández never recovered from his early-thirties velocity drop, and the early returns on Madison Bumgarner aren’t promising. The community still waits with bated breath to see where Chris Sale’s velocity will be when he (presumably) returns late in the year—and what he’ll do about it if it continues to decline.

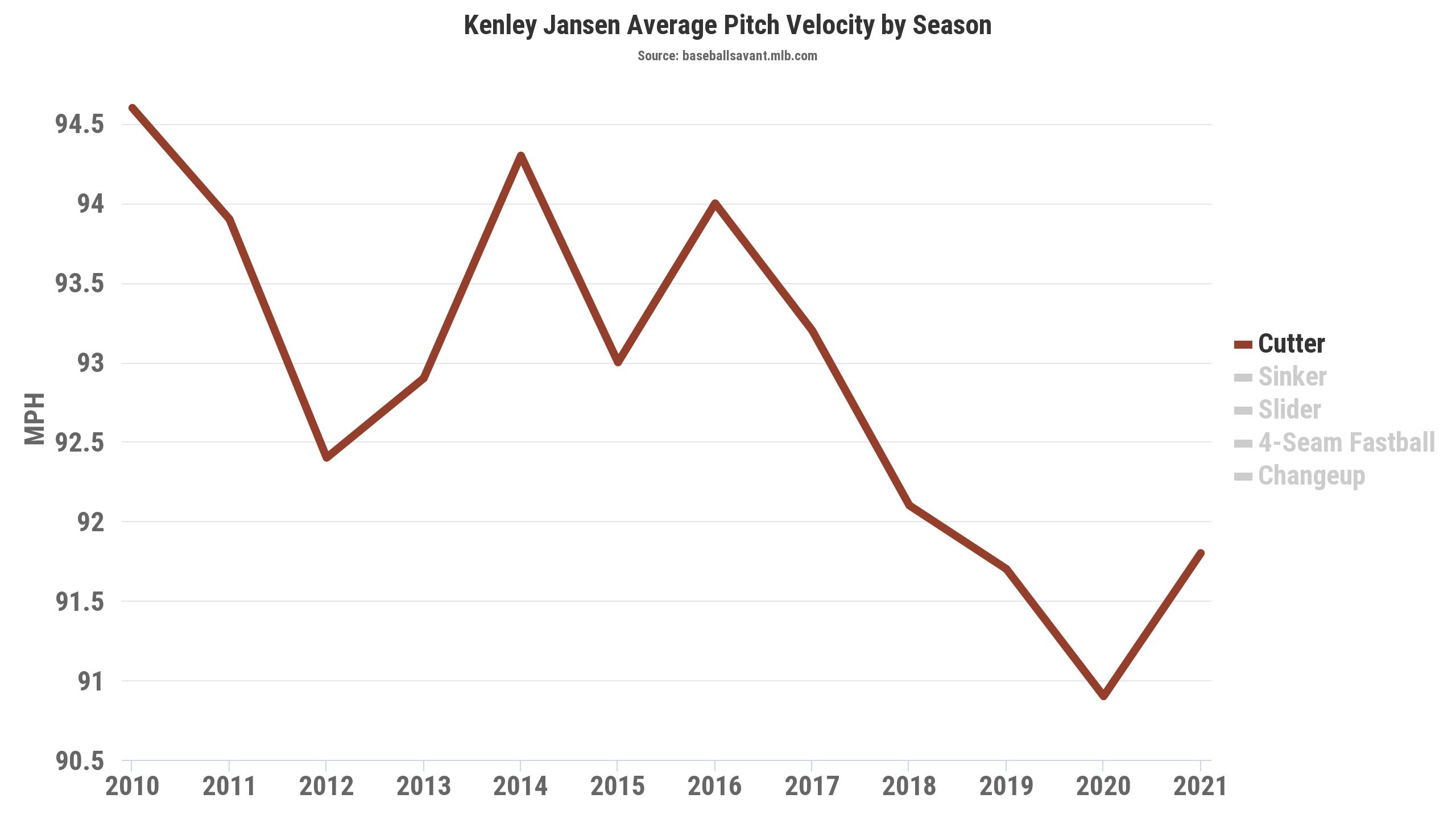

This is the kind of crossroads that Jansen finds himself staring down. There have been obvious adjustments years in the making; this is the fourth straight year his cutter usage has declined. His stat line is interesting, and there’s a fair share of oddities in that grid up there. I’ll try to tell a story in a series of visuals. First, here’s the velocity of Jansen’s cutter over the years.

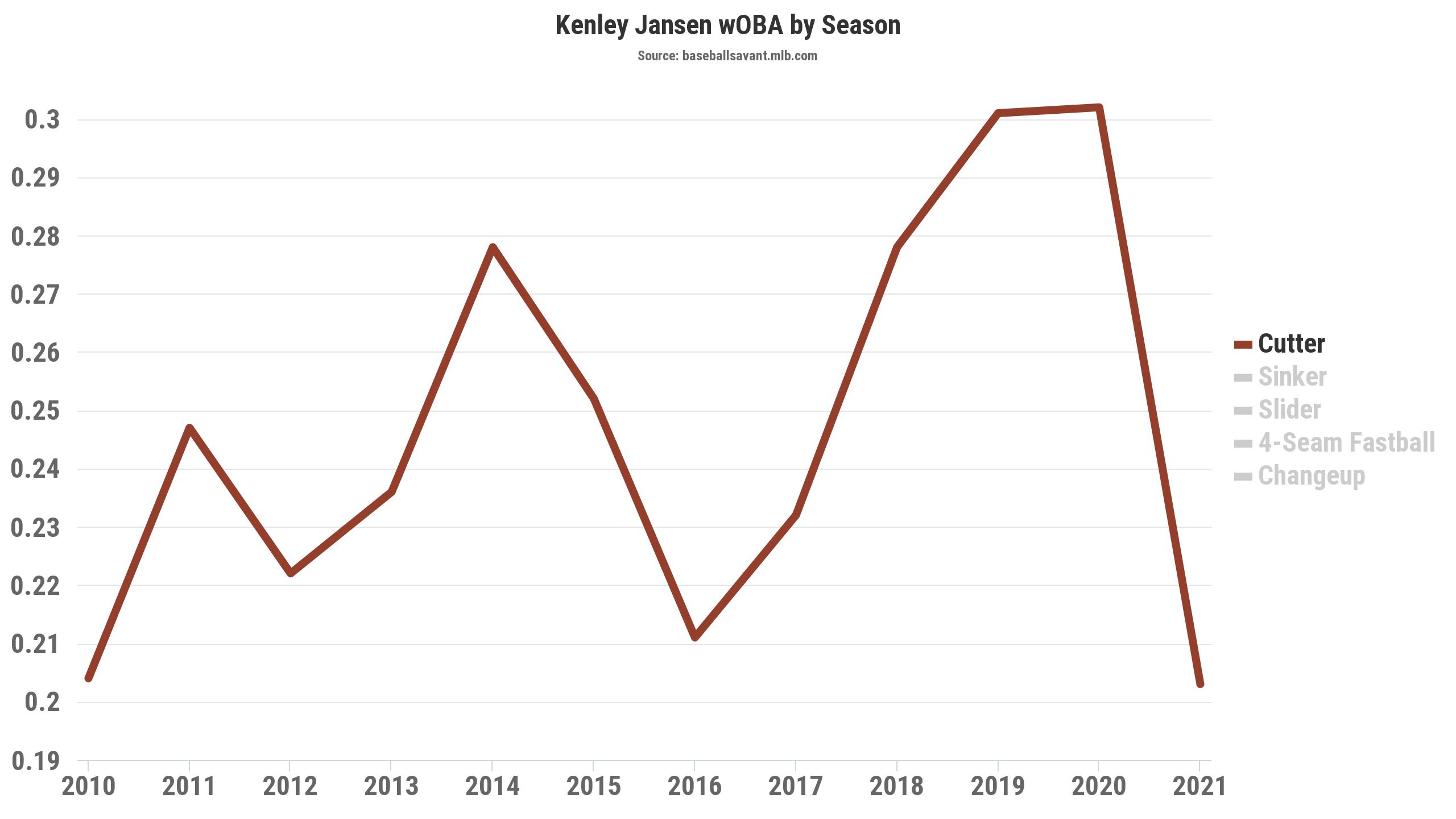

Following, here’s the cutter’s wOBA over the years, a pretty solid catch-all for how effective a pitch has been over a large sample.

That’s nice! The velocity rebounded a little, the effectiveness rebounded a lot, and the Jansen that we know and love is back, right?

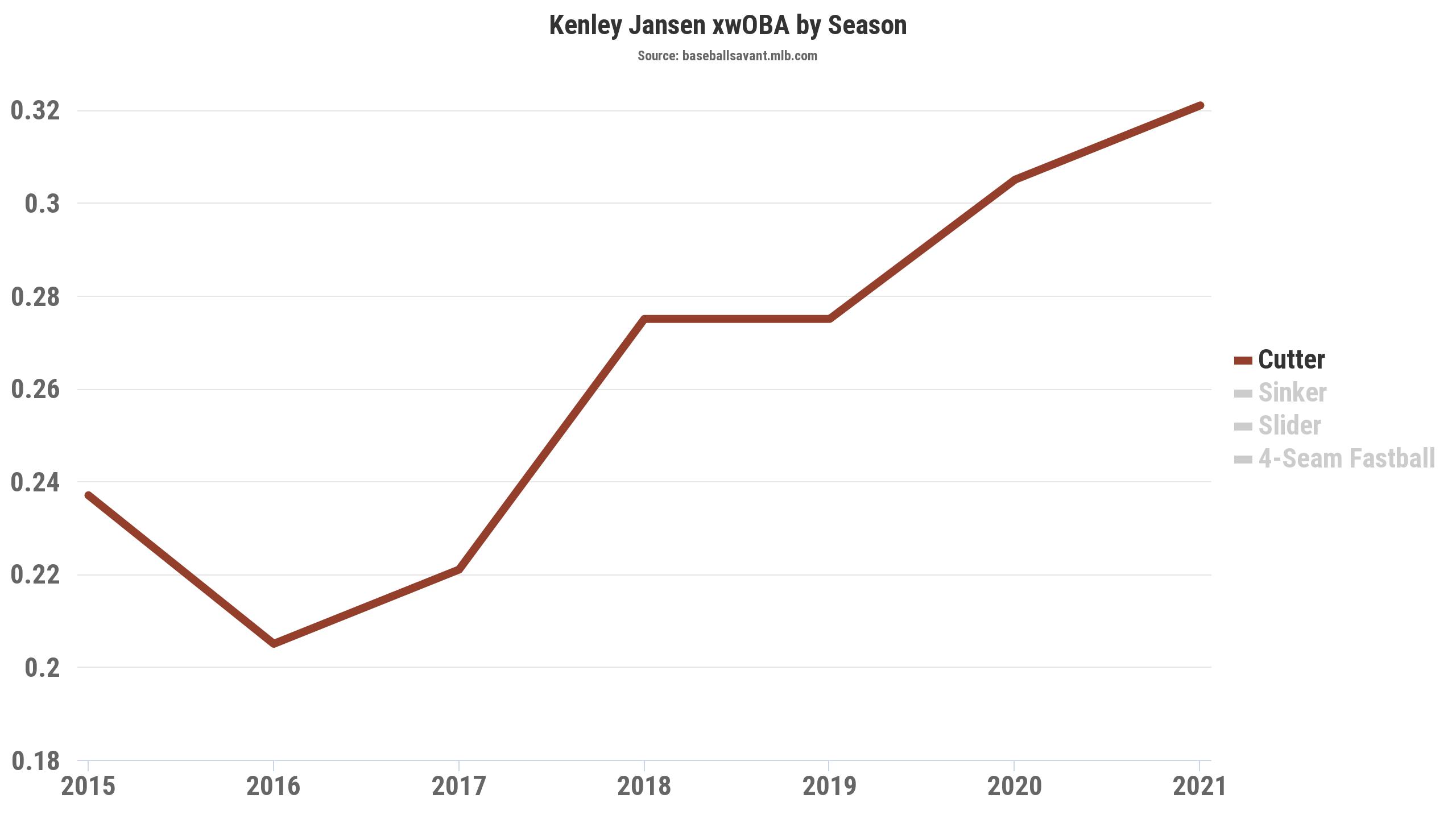

Not exactly. If the depressed strikeout rate and way elevated walk rate weren’t indicators enough, most of the data we have just below the surface tells us that a reckoning is coming for Kenley and his overperforming cutter. In spite of the wOBA rebound, the expected wOBA is thoroughly unconvinced that the pitch has any of its old mojo back.

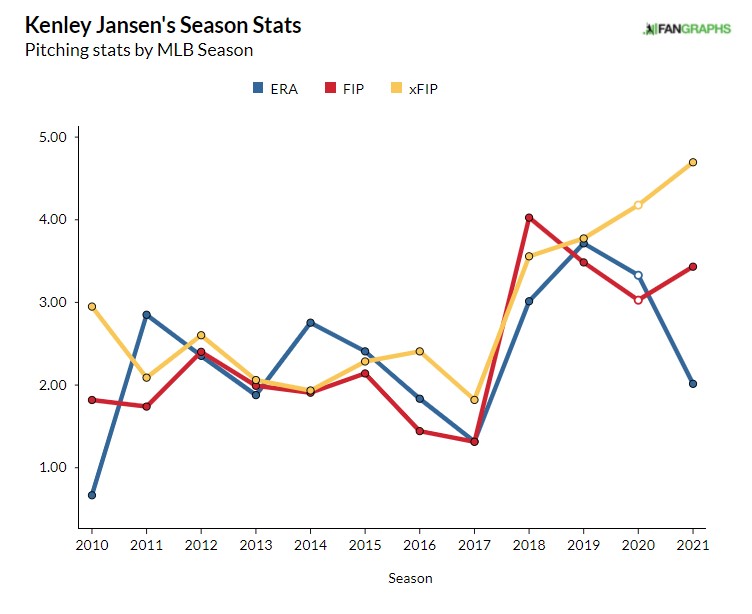

Oof. Similarly, ERA estimators seem the think that Jansen’s downward progression (or, in the ERA sense, upward progression) continues to be more or less linear, whether the results say so or not.

That’s a bit disappointing. Another check in favor of “it’s a mirage” is the fact that it doesn’t take much digging to figure out where the big disparity in ERA and peripherals is coming from. As it turns out, Jansen has been the recipient of some of the best batted ball fortune in the league so far this year, ranking third among all pitchers (min. 20 IP) with a minuscule .140 BABIP.

BABIP is a super flawed stat that should rarely be given without context, so I included the ERA estimators there because I think it highlights something interesting. Because FIP and xFIP treat batted balls as essentially out of the pitcher’s control, we can see how those stats severely ding pretty much every pitcher getting an unsustainable number of outs on balls in play (just as instructively, Karinchak and Antone demonstrate that if you strike out enough hitters, batted ball luck only matters so much). Meanwhile, Richard Rodriguez is a lab-tested case for the difference between FIP and xFIP—FIP gives him credit for the big fat 0% HR/FB he’s allowed this season, whereas xFIP thinks the proportion of homers to fly balls is also a factor of luck, and therefore believes he’s due for a rash of runs sometime soon.

At the same time, expected ERA (xERA), which is just pitcher xwOBA converted to an ERA scale, paints a bit more of a nuanced picture. Because it uses Statcast’s batted ball data, it should (in theory) do a better job than FIP or xFIP of telling us which low BABIPs are “earned” via lots of weak contact, and which aren’t. Jorge Alcala and Jake Brentz, unfortunately, are getting quite lucky just about any way you break it down. Sorry, guys.

So the big gaps between xERA and FIP/xFIP are the cases where contact suppression warrants a closer look. I don’t know too much about J.P. Feyereisen, but I do know that if the Rays acquire someone and instantly give them a bunch of save opportunities, it usually means they’re pretty good. I’ll take the time to figure out whether Trevor Bauer’s ERA is real as soon as he takes the time to figure out whether climate change is real.

Like I said, BABIP is super flawed, and there are other ways we can try to test whether Jansen’s contact suppression has any merit to it. One of them is a Statcast metric called wOBA on contact (wOBACON), which is roughly analogous to wOBA in the same sense that BABIP is to batting average. By removing strikeouts and walks from the equation, we’re left with a number that more or less gives us a wOBA value that we can line up with barrels, exit velocities, and other measures of batted ball quality.

Because we’re still talking about results, wOBACON and BABIP are going to correlate fairly closely. So it shouldn’t be surprising that Jansen is third in all of baseball with a .180 wOBACON allowed, or that three other members of the BABIP leaderboard (Shaw, Rodriguez, and Antone) appear in the top-11.

Fortunately, for every Statcast stat, there’s an expected Statcast stat. Unfortunately, Jansen has one of baseball’s biggest gaps between his wOBACON and expected wOBACON. This suggests that not only has he been lucky in the sense of a general rule stating that low BABIPs are usually reflective of good fortune, but he’s also been lucky in the very concrete sense that a fair number of well-struck batted balls are being turned into outs.

We’ve got some familiar names because all of these numbers are somewhat interdependent. Either way, this is a very long-winded way of saying that while Jansen’s run prevention has, by and large, returned to its prime days, he’s needed a lot more help to achieve those numbers than he did back in the day.

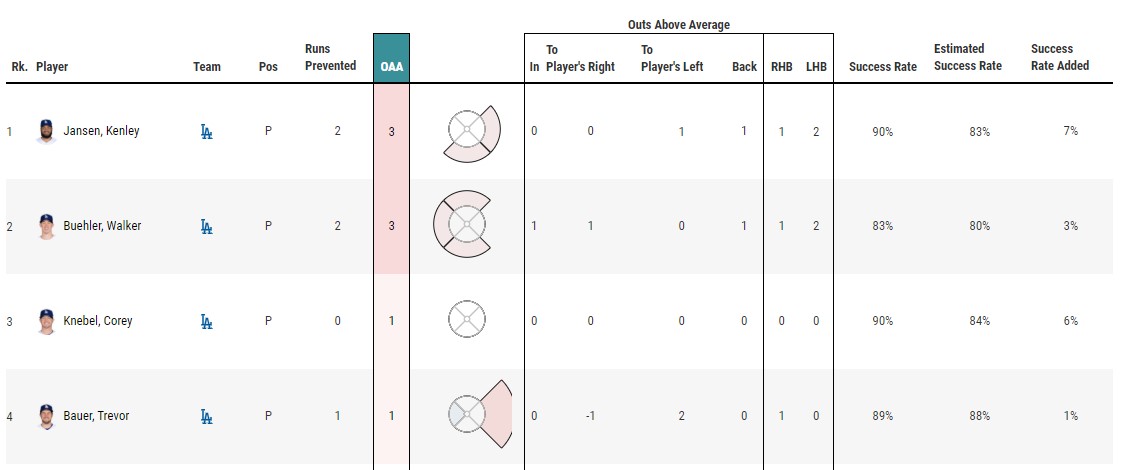

As always, this is little more than a patchwork of guesses and darts thrown at the wall, but there are two things constitutive of Jansen’s contact suppression and batted ball results that might be read as repeatable skills, rather than simple luck and random variation. The first is defense. Justin Choi recently covered the weird and extreme ways that the Dodgers play defense to their pitcher’s strengths, and according to Outs Above Average, no Los Angeles pitcher has benefitted from good defense more than Jansen this season.

The two runs prevented by the Dodgers defense according to OAA is, by itself, the difference between Jansen’s current 2.01 ERA and a 2.88 mark almost perfectly in line with his xERA. Truthfully, whether that’s going to keep up or not is a complete and utter mystery to me. In 2020, defense saved a single run for Jansen, but in 2019 it cost him one. In 2018 it saved him three. Somewhat surprisingly, the 2021 Dodgers are just 23rd in the league with six outs below average cumulatively. Those two runs might not make a huge difference in the grand scheme of things, but it’s still another check against Kenley being a true-talent 2 ERA pitcher at this point in his career.

This is where learning how to pitch enters the equation. The main question has been answered. At least relative to norms across the board, Jansen has had a good degree of demonstrably good fortune, much of it coming from his defense. But from an evaluative standpoint—I’m not taking a purely probabilistic view, to be clear—the only way to really make an educated guess as to the sustainability of this version of Jansen is to ask whether he himself is employing repeatable skills that aren’t being reflected in the litany of numbers we’ve looked at so far.

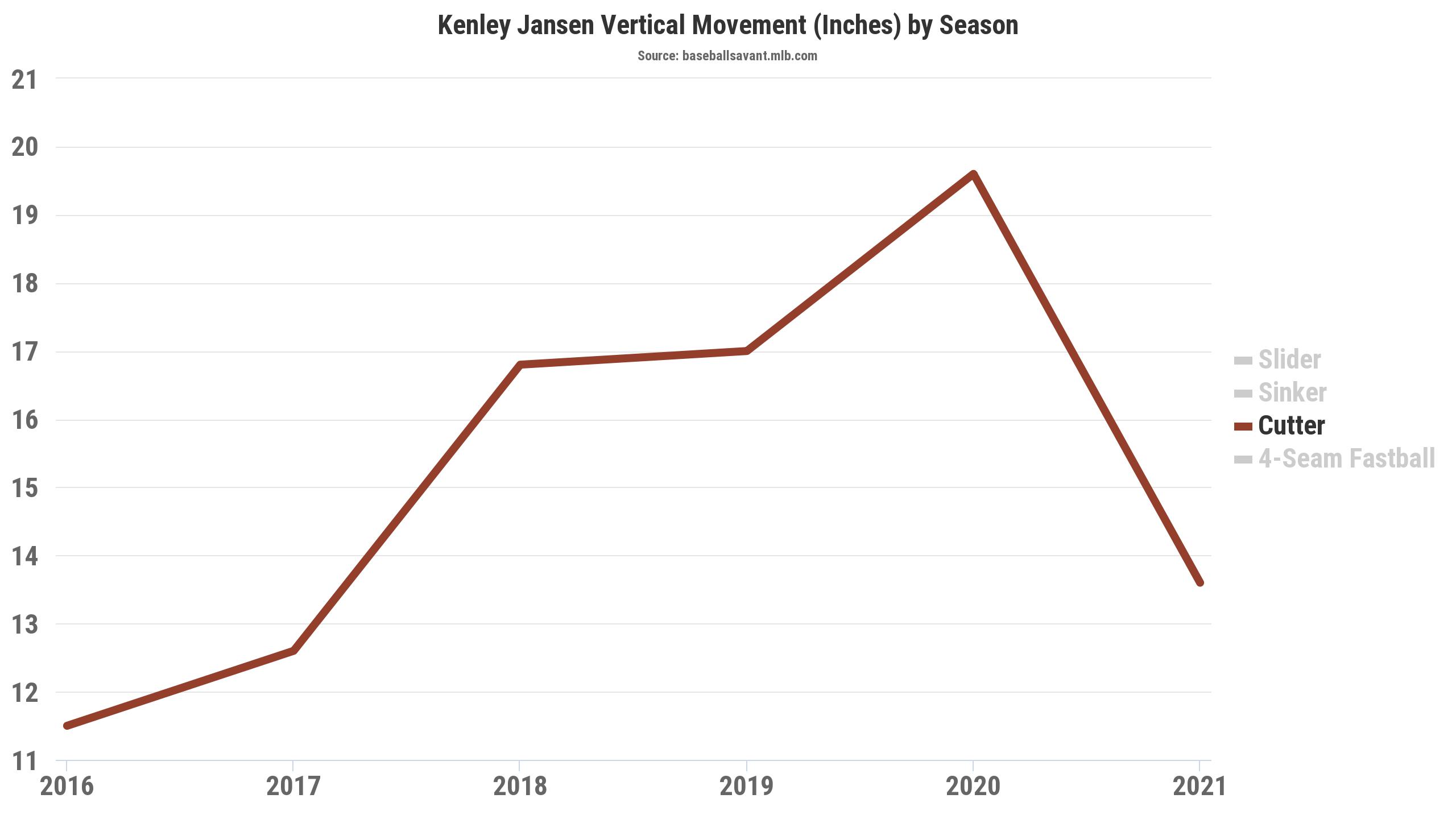

A look at Jansen’s pitch data brings us to the second (and more critical) site where a truly repeatable skill might be at work. I’m 1500 words into this article and I still haven’t even looked at the things that are within the pitcher’s control! As Kenny Kelly discussed recently at Beyond the Box Score, the rebound in velocity isn’t the only thing that’s changed about Jansen’s cutter—after years of adding more and more drop to go along with the decreased velocity, the vertical movement on the pitch has rebounded to its highest levels in years. As always, remember that fewer inches of movement mean more rise.

Kelly did a fine job of breaking down some of the reasons behind this, so I’ll leave the details to him. What you need to know is that the spin rate on Kenley’s cutter has mysteriously spiked by 300 RPM, while its active spin—that’s the proportion of the spin rate that actually causes movement—crept up from 71% to 79%, an abnormally high rate for a cutter, which usually involves a lot of gyro just by virtue of the way it’s thrown. I’m not here to speculate on how that happened, but it sure answeres the question of where all that extra rise came from.

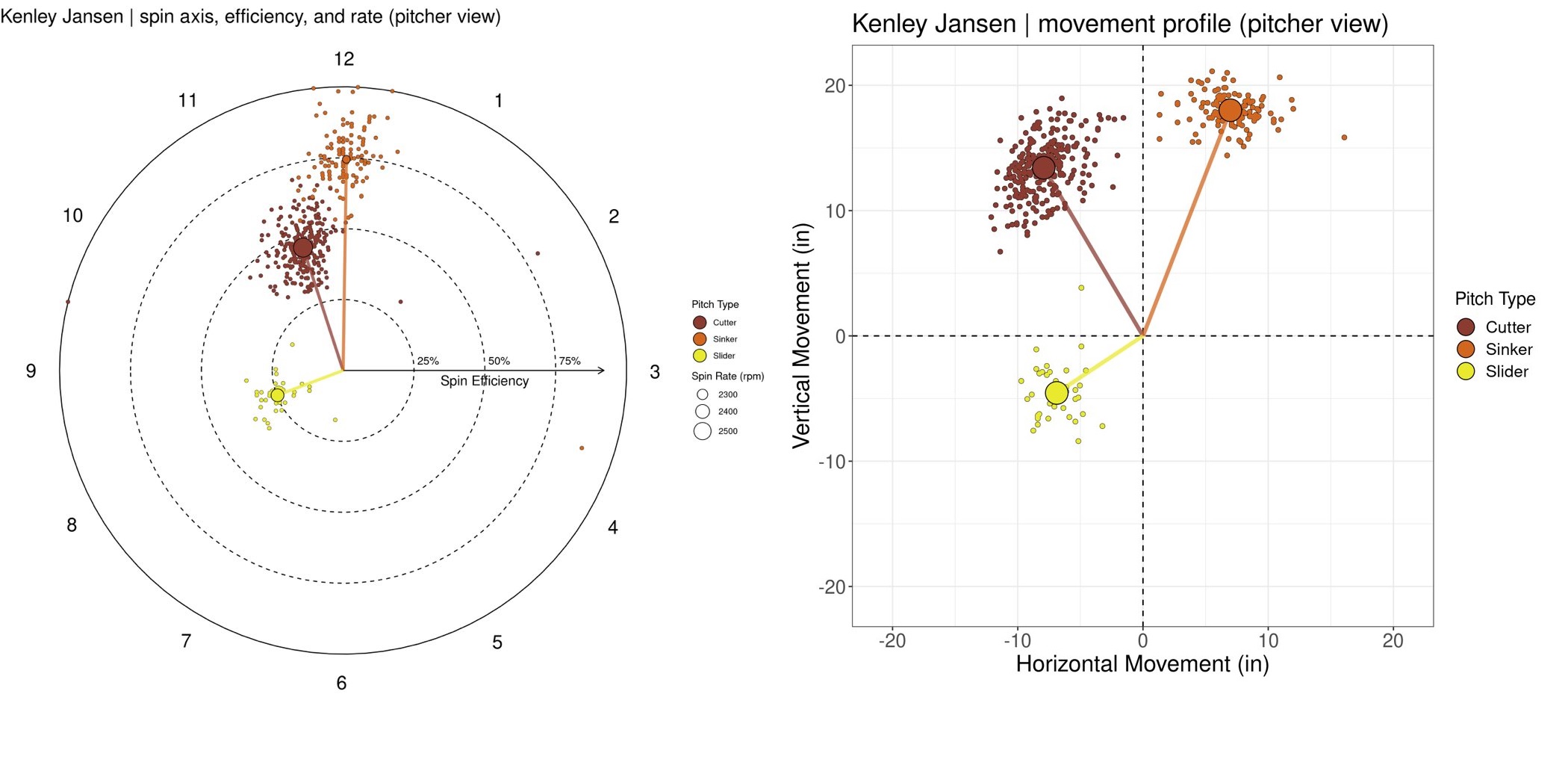

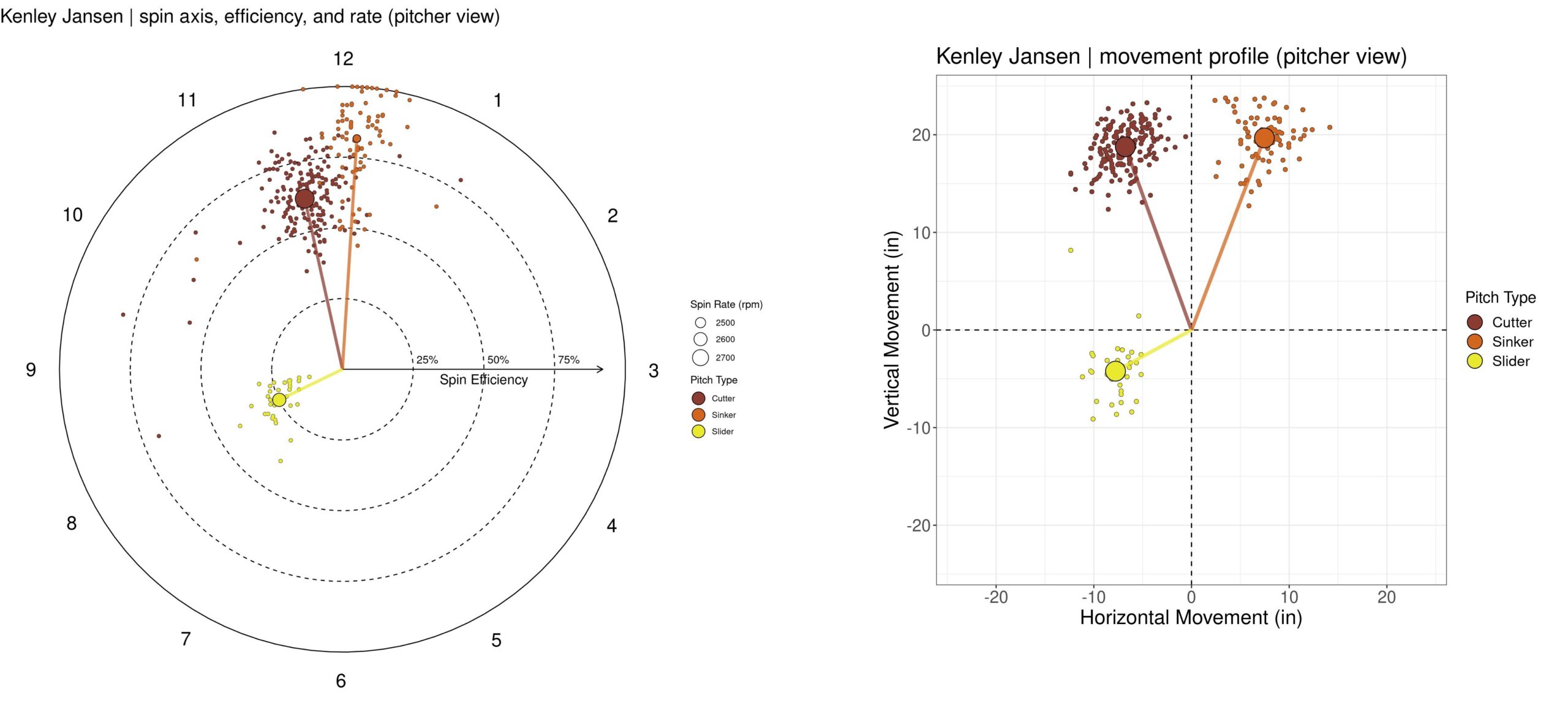

Visualizing those numbers gives us a hint at where we might find the skill in Jansen’s contact suppression. Courtesy of Max Bay (@choice_fielder on Twitter), we can take an all-in-one look at how these changes are manifesting on a pitch-by-pitch basis. 2020 is on top, 2021 beneath it.

These changes are subtle, but the way that both the spin direction and spin efficiency between his cutter and sinker have blended slightly closer together this season could have real implications on movement and how hitters read pitches. If you have trouble seeing the difference in the chart on the left, it should be clearer on the right.

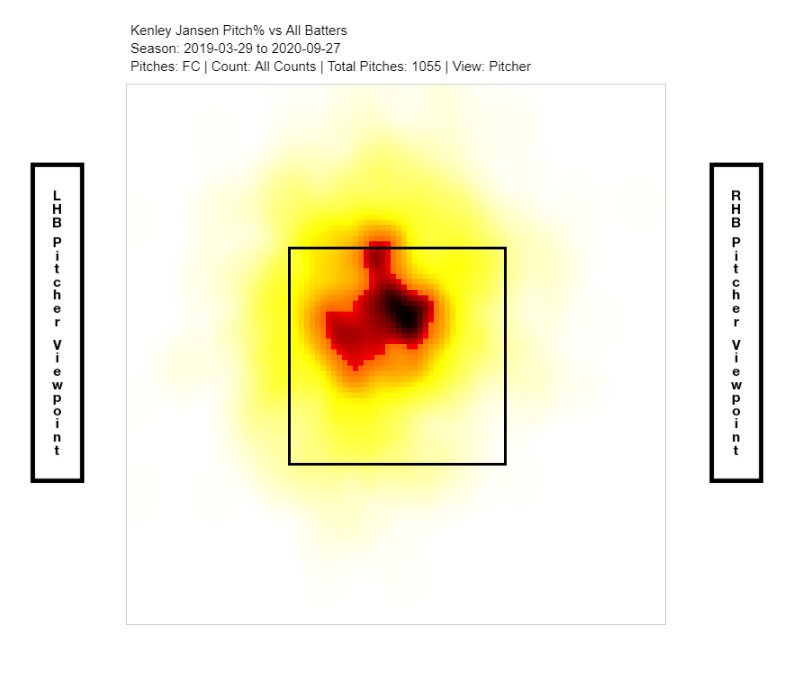

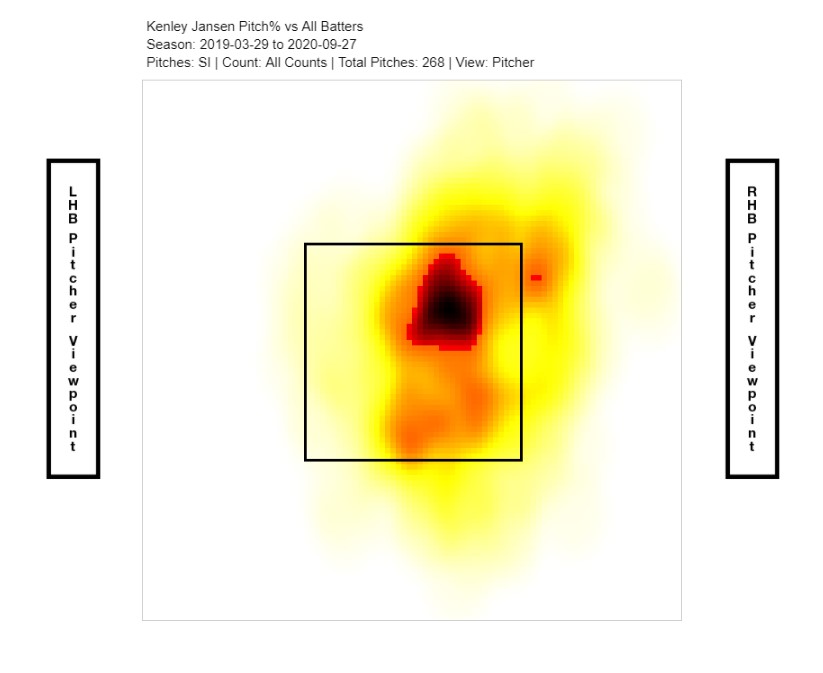

While the cutter’s adjustment by itself doesn’t look particularly drastic, what stuck out to me was how the two pitches now mirror each other almost perfectly in terms of movement. Considering the relatively small velocity gap between them, this opens up some interesting possibilities in terms of deception. When location heat maps for the two pitches are brought into the equation, those possibilities start to look very possible. Here’s where he threw his cutters (left) and sinkers (right) between 2019 and 2020.

|

|

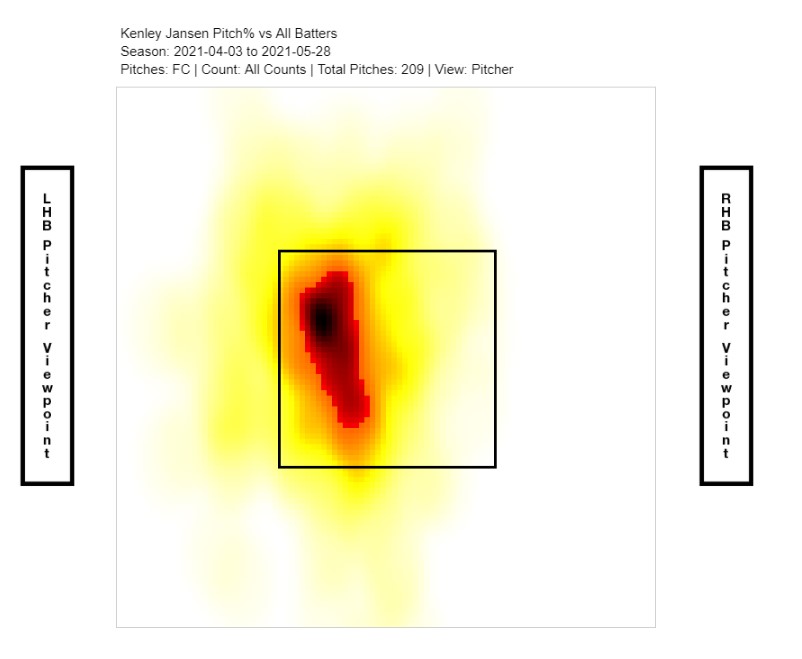

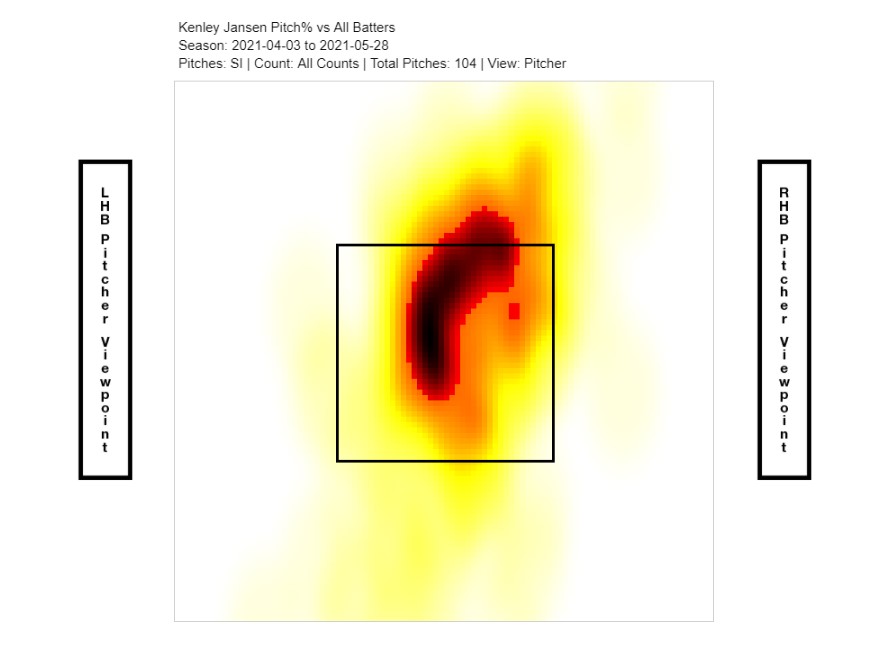

Here’s where he’s throwing them this year.

|

|

Now some things are starting to click. On the one hand, we have at least a partial explanation for the massive spike in walk rate. Even though Jansen has brought his sinker much more into the mix recently, he still throws the cutter the large majority of the time, and now he’s throwing the cutter near the edges of the plate more than he ever has before. Consequently, his zone rate is at the lowest of his career at just 46%.

In a nutshell, that’s why I’m not particularly inclined to buy into the added walks as a long-term problem. As Noah Scott (@noahscott6) pointed out to me while discussing Jansen, the stellar walk rates he posted earlier in the decade are a bit misleading, with regards to his control and command. Jansen was never much of a control artist, Noah reminded me, but he ran absurd walk rates because the cutter was so good that he was able to more or less throw it down the middle every time and let hitters do what they could.

Now, that version of his cutter is gone. Jansen can’t afford to live over the middle anymore; when his velocity faded, his home run rate leaped up. Now, he’s learning how to pitch. He’s living more on the edges, and to work with the walks that come with not being able to get hitters to miss quite as much. Without the stuff to run strikeout rates near 40% anymore, he’s learning to pitch more to contact and let his fielders take care of the rest.

Those heat maps also give us a hint at why Jansen has been so good at pitching to contact, even when the numbers say he probably shouldn’t be. Put all three of those charts together, and you get the idea. It looks something like this.

Kenley Jansen, 94mph Two Seamer & 95mph Cutter Movement (close up). ? pic.twitter.com/n2g4NUttWr

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) April 21, 2021

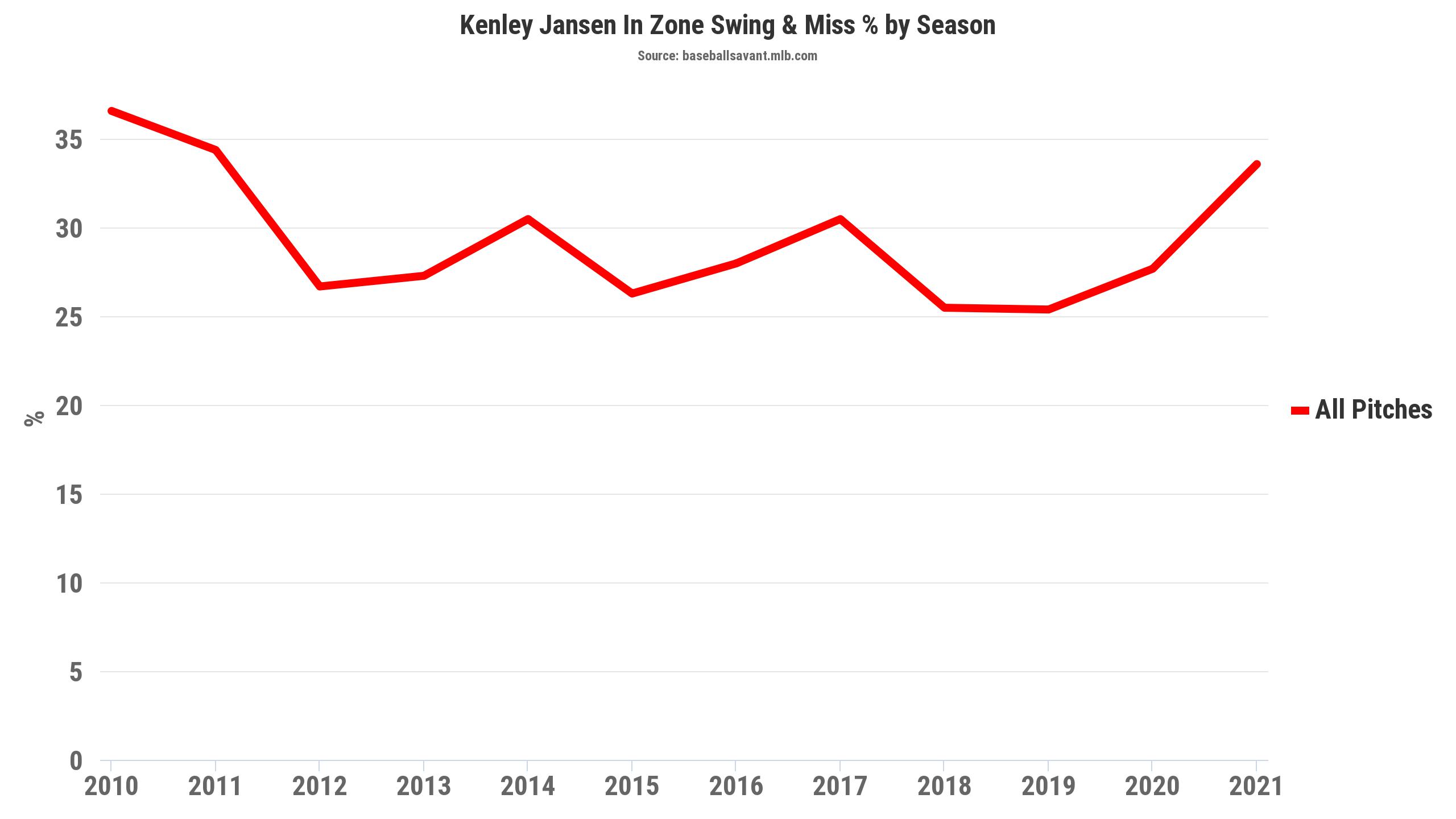

Those two pitches were at 95 and 94, so they represent the best that Jansen is showing this year, as mechanical consistency and fluctuating velocity continues to be an issue for the future Hall-of-Famer. But it represents the way that he’s been operating this year. While most of this article has been checks in favor of Jansen’s luck running out sooner or later, it’s also worth noting that his in-zone whiff rate is the highest it’s been in a decade, with an increase over last year that far outpaces the overall increase in whiffs league-wide.

All of this is what I might describe as learning how to pitch. At 30% usage, Jansen now throws his sinker enough that hitters have to seriously take it into consideration when they’re at the plate. Now keep in mind that, as we saw above, the pitches are very similar in terms of spin, in that they point basically in the same direction and are separated only by about 15% worth of gyro spin. But because of different grips and seam orientation (aka, the way Jansen holds and releases the ball), they move in opposite directions horizontally while staying pretty much identical vertically. That’s a lot of deception at play, especially for someone who spent most of their career as a one-pitch, “here it is, try to hit it” type power pitcher.

For most of his career, hitters knew exactly what they were getting out of Jansen. They just couldn’t touch it. Now, with his stuff diminished, that approach is out the window, from the pitcher’s perspective. Now, Jansen has re-shaped his arsenal so that hitters don’t know what’s coming until the last possible minute.

Put together the location charts with the heat maps (and the GIFs) and it’s pretty easy to visualize. Jansen still throws most or all of his pitches to roughly the same spot. That spot is just a little more off the center of the plate than it used to be. Even assuming that a hitter can read the slider the 10% of the time Jansen throws it, they’re still going to be unsure of what they’re getting almost to the point where the pitch either breaks towards or away from them. But by then it’s too late.

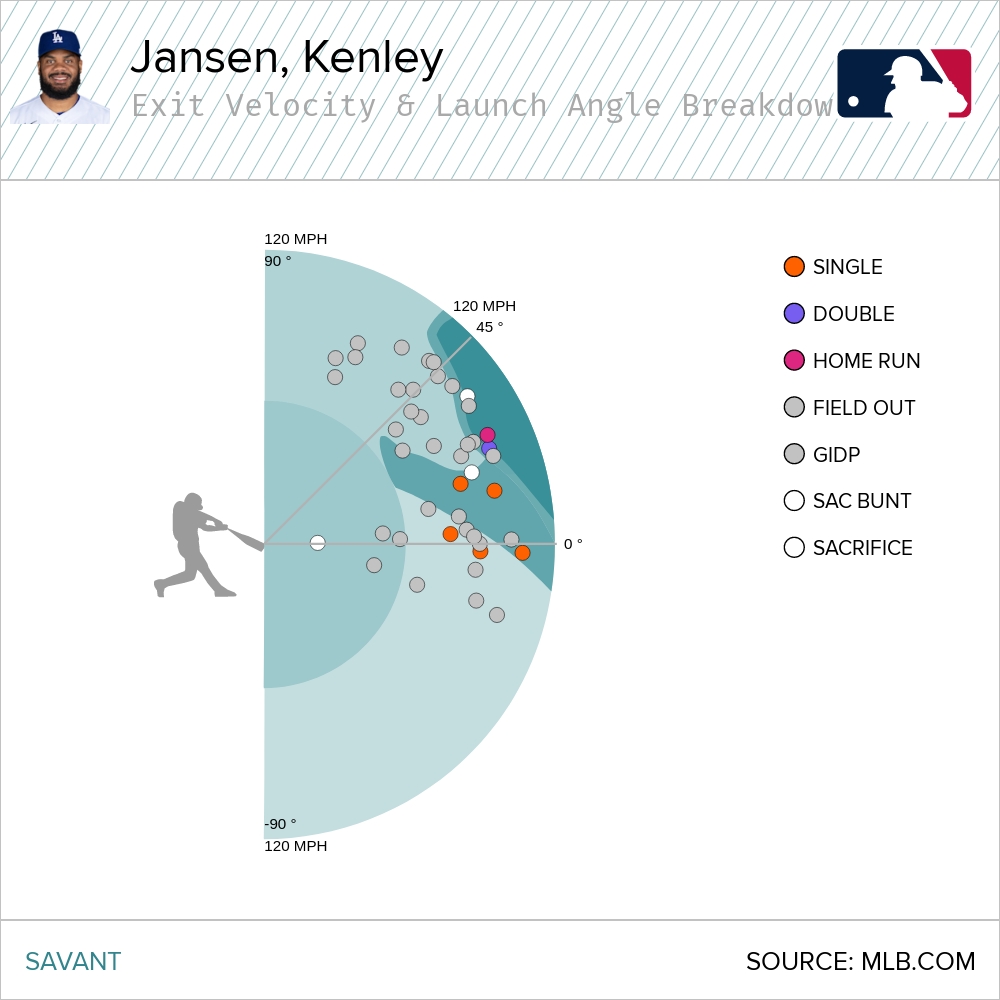

It’s easy to see how in addition to the in-zone whiffs, the added deception could lead to an absolute boatload of weak contact. Even at his worst in recent years, Jansen was still fairly good at managing contact. Alex Chamberlain has come up with compelling evidence that pitchers have an exponentially greater influence on a batted ball’s launch angle than its exit velocity; that is to say, pitcher’s can’t control how hard a ball is it, but they can do their best to make sure it’s not hit in a dangerous spot. His batted ball chart is as good as ever, with almost everything being popped up or driven into the ground.

Following that train of thought, the numbers say that Jansen is one of the best in baseball at producing “bad” launch angles. Just 25% of batted calls against him have been in the “Sweet Spot,” the space between an 8 and 32-degree launch angle where the large majority of offensive damage is done. That’s the lowest number of his career, and ranks 23rd out of 332 qualifying pitchers. Even if he can’t miss bats he used to, he seems to have gotten even more adept at missing barrels. It’s not quite as useful as drawing whiffs, but it’ll certainly extend one’s career. Again, learning how to pitch.

Those are a lot of things working in conjunction to keep Kenley Jansen a highly effective closer. Some of them might be sustainable, some of might not be. Absolutely all of this could change in the next two or three months and make me look like a fool. Regardless, it’s clear that he’s making more adjustments now than he ever has before. Though he’s not the force of nature we saw in years past, he’s finding other ways to get it done. So while some peripherals and underlying numbers might see a continuation of the downward trajectory he’s been on for the last several years, it’s not quite that simple. It’s impossible to say whether the changes he’s made will keep him super-effective, but it’s clear that this season isn’t as much of a fluke as a glance at those peripherals indicate. A triple-digit fastball or 95 MPH cutter with 10 inches of sweep might involve many nuances, but they can’t last forever. And it’s never too late to learn how to pitch.

Photo by Brian Rothmuller/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)

Are you trolling me? Kenley Jansen is one of the very best closers of all-time. His approach is s simple as anyone to ever step on a MLB mound. I do not buy for one second that Kenley is doing anything any differently than he ever has. It is one classified pitch thrown right down the middle day after day, year after year. This is just regressive pitch classification analysis. Pitch classification swings and missed when it comes to fastballs, which is all that Kenley throws. He does mx in a CB that he calls a SL but that isn’t what makes Kenley the man. I am absoultuel certain that Kenley has made zero adjustments – the analysis surrounding him gets more absurd but he is exactly the same guy. He is the same guy that everyone has tried to bury so many times. He has not adjusted – people were just wrong. I am probably Kenley’s most vocal advocate on the Internet – it has been that way for years. Literally pissing into the wind as people want to declare the decline over and over again. Look at the numbers. He has never not been great. Kenley doesn’t do anything cute. Half the time it is FB right down the middle. Kenley is as stubborn as the day is long – that guy is not adjusting. He just throws a FB that people can’t hit. The only thing we should be talking about it how far behind Mariano Rivera he is as the greatest of all-time. I think that he is the second greatest of all-time and here we are discussing whether he is for real? Kenley is as simple as it gets. Please watch some Kenley and appreciate what is always going on… he throws a bunch of FB and people struggle with them. Sometimes they stare at them right down the middle, they often times miss badly and a lot of the time they fight them off. Think about that – one pitch, likely in the heart of the plate and they have no idea what to do with it. My theory is that he is 100% focused on putting as much spin on the ball as possible, which is why the velocity is inconsistent. Kenley’s disastrous 2020 was not disastrous at all – I believe his career worst WHIP is like 1.16. If the Dodgers were not constantly actively seeking to destroy his legacy his number would be a bit prettier, but they are beautiful even with all of his struggles. The pitch binning on his cutter and sinker is so bad that it is worthless – those are just fastballs and half of them are wrong I am sure. It doesn’t really surprise me that the fine points of pitching are completely lost in machine analysis. I watch games and follow the pitch classification and it is putrid for FB artists – like incredibly bad. The dude is a magician and most people are missing the show.

“If the Dodgers were not constantly actively seeking to destroy his legacy his number would be a bit prettier, but they are beautiful even with all of his struggles.”

Are you crazy? The Dodgers have kept him as their closer even when he’s DRASTICALLY under-performing. They put him right back in there after he had HEART SURGERY.

I’m used to your regressive rants here, but this one really takes the cake. I’m nothing even close to a Dodger fan, but I can’t just sit here and let someone talk crap about how they’ve treated Jansen. On almost any other team, Jansen would have been put out to pasture loooong before this resurgence.

As far as J.P. Feyereisen, he’s a bit of an anomaly… I can’t find the article from earlier in the season, but he uses his pitch-mix in quite an unusual way. I’ve liked the guy since he was a Yankee farmhand, and the Rays did too, it seems. If I remember the article I’m thinking of correctly, he places his slow pitch (which is more of a 2-seamer than a change,) and sliders where batters aren’t used to finding them, breaking into the zone higher than usual and getting grounders and K’s out of them while his 4 seamer has top-level effective spin.

All of his pitches have that spin “it-factor.”