In the summer of 2021, Casey Drottar followed the Kane County Cougars through their first season after the team lost its MLB affiliation. This is the first chapter of his four-part story on how they survived.

***

Curtis Haug bounds into the press box at Northwestern Medicine Field 10 minutes before first pitch, boasting a mood that hardly corresponds with the weather outside. A persistent drizzle looks to hover over Geneva, Illinois well into the night, threatening to derail the Kane County Cougars’ first game in 621 days. But the team’s general manager confirms otherwise, giddily insisting the May 18 season opener is good to go.

“We waited almost two years for this,” Haug says. “We’re not going to let a little rain stop us.”

He turns to exit. As the door closes behind him, a voice can be heard kicking off the 2021 season in defiant fashion.

“Major League Baseball can’t tell us what to do anymore.”

You’d be hard-pressed to better summarize the past 18 months for Kane County. Like all Minor League Baseball teams, the Cougars had their 2020 season canceled due to the coronavirus pandemic. Unlike 120 of those clubs, Kane County wasn’t invited back the following offseason. Major League Baseball contracted its minor league system that December, setting 40 teams adrift to find a new home, one which wouldn’t feature any financial support from a big-league affiliate.

The Cougars endured an entire summer without revenue, only to find out their next season would be completely self-funded.

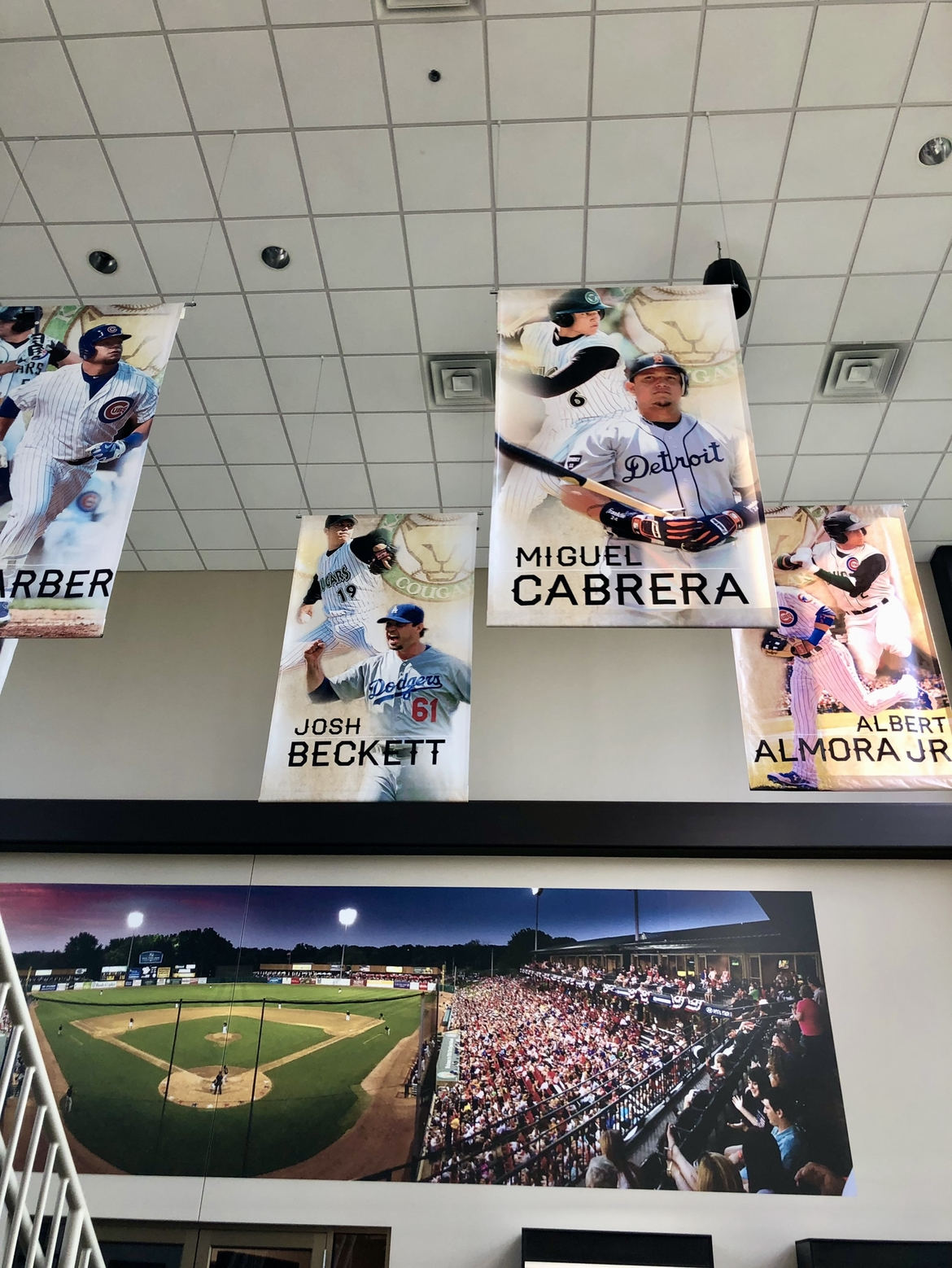

Down on the field, Kane County’s 2021 roster is on display, looking remarkably unfamiliar to the rain-soaked supporters in the stands. Since 1991, the Cougars offered their fans a chance to see future MLB stars before they made it big. Nelson Cruz. Josh Beckett. Miguel Cabrera. Each once called Kane County home before carrying on big-league careers that featured various MVP awards and a combined 21 All-Star appearances.

Now, the Cougars’ infield is manned by a second baseman who once almost gave up on baseball and joined the police academy. A recent college grad owns a spot in their pitching staff, solely because of a personal highlight video he posted on Instagram. The son of an MLB pitching legend was supposed to take the mound for Kane County, as well, but a lingering injury is forcing him to maintain a roster spot with his bat.

There are no first-round draft picks to be found, no blue-chip prospects a major league club is counting on Kane County to develop. This team instead features numerous players who spent the past year wondering if they would ever take the diamond again.

“There’s still a lot of good players out there that don’t have jobs,” says 25-year-old outfielder Mark Karaviotis, who waited 10 months to find a new team after being released by the Visalia Rawhide. “Just being able to compete again, I definitely won’t be taking that for granted.”

The Cougars’ roster is comprised mostly of players who’ve come here to revive dreams once deemed futile. And for the first time in the team’s 30-year existence, Kane County has to foot the bill for every single one of them. Now a member of an MLB Partner League, the Cougars must find and pay their own talent, with the knowledge that a big-league club could come and take any player off the roster at a moment’s notice.

That reality check arrived just six days before the season opener, with the Minnesota Twins plucking infielder Sherman Johnson away from the Cougars. Unlike the setup Kane County is used to, Minnesota didn’t provide a replacement. Just a check and a roster void in need of filling.

Welcome to a life unaffiliated.

***

GENEVA, Illinois, May 18 – The Cougars’ first game in an MLB Partner League ends in a 6-4 defeat to the Chicago Dogs, and a lengthy one at that. The contest lasts a hair over four hours, with rain continuing until the sixth inning. This makes for an overall sloppy affair, a display of pitchers attempting to tune up their curves and sliders on a night when gripping a baseball qualified as a superpower. Three batters were beaned, one of them twice, and that number threatened to rise multiple times throughout the night.

“Nobody likes playing in weather like that,” manager George Tsamis says afterward. “You just try to get them in. We got through it. Hopefully, that doesn’t happen many more times.”

The atmosphere in Kane County’s clubhouse remains upbeat despite the result. For many, the night served as their first professional game in two years. For all, it was the start of a new era of Cougars baseball. One for which Tsamis believes he has armed himself with a high-quality roster.

“They want to win,” he says of his players. “They’re here, they have the right attitude. We just didn’t get it done today. Tomorrow’s a new day.”

***

Like many front office veterans, Scott Lane had been closely monitoring the contentious 2020 talks between MLB and Minor League Baseball. He was two years into retirement after spending over two decades as president of the West Michigan Whitecaps, a Detroit Tigers Single-A affiliate. Before that, he joined the Kane County Cougars in 1991, signing on at the team’s inception as its first assistant general manager.

As he waited to see which clubs would be displaced from the minors, Lane comfortably assumed Kane County was safe. In fact, considering the history of the franchise, the idea of his former club being ousted didn’t even dawn on him.

On December 9th, MLB released its list of the 120 teams that would remain affiliated in the reorganized minor league system. The Cougars were nowhere to be found.

“When I saw the final list,” Lane said, “I called the owner of West Michigan and I said, ‘What in the hell is going on? Why is Kane County out?’ It just blew our mind. For the life of me, why would Kane County lose a Major League Baseball affiliation?”

The answer to that has yet to be provided to the Cougars, though several league insiders have speculated the cause, positing hypotheses that range from simplistic to nefarious. Some say it was merely the result of their having no local big-league affiliate. Others went a step further, insinuating this was a form of MLB payback for something Kane County did to upset the Cubs when the teams’ suspiciously swift two-year affiliation ended in 2014.

Whatever the cause, confusion about the final decision remains within the Cougars’ front office. Warning flags arose in the days leading up to the contraction announcement when their previous affiliate – the Arizona Diamondbacks – ended its partnership with Kane County. But the team boasted frequently lauded stadium facilities and a strong reputation with MLB, two factors that played a major role when the league evaluated which clubs to keep. The Cougars getting kicked off the MLB pipeline despite those two key elements was difficult to comprehend.

“It’s almost like we were lost in the shuffle,” said Haug, who originally joined the team in 1993 as a group and sponsorship salesman before working his way up to general manager. “It was inexplicable to us that Major League Baseball would contract a team that had such a great history. We pioneered a lot of things for, not just minor league baseball, but minor league sports in general.

“Attaching ourselves to a major metropolitan area, no other team had done that. We took that shot back in 1991.”

Such a task seemed like a fool’s errand at the time. The then-Wausau Timbers were already struggling financially in 1990. Relocating to Kane County and making a home just 42 miles west of Chicago to compete with not one, but two Major League franchises didn’t seem like a viable solution.

To make it work, the Cougars needed someone unafraid of the challenge ahead. Someone crazy enough to see competing with the Chicago Cubs and Chicago White Sox not as impractical, but advantageous.

They found that person when they hired Bill Larsen as general manager.

“I contacted the owners, and said, ‘I don’t know if you’ve got someone in mind,’” said Larsen, who was working as general manager for the Rockford Expos at the time. “Most people in baseball shied away from even thinking about the position. The competition that was there with the Cubs and Sox really discouraged a lot of people. I was probably the only one that believed it could happen successfully.”

Larsen knew the market well enough, having grown up in Jefferson Park just northwest of Chicago. But convincing Cubs and White Sox fans to come to the suburbs and watch Single-A baseball would take more than a familiarity with the surrounding area. Larsen hit the ground running, taking up residence just outside the stadium and clocking 24-hour workdays to strategize.

“He was living in a rundown house when he got the job in Kane County,” Lane said of his former boss. “It was crazy. Bill could read the tea leaves. I couldn’t, but he convinced me that we had the opportunity to do something very special with minor league baseball. He was right.”

What once was—Kane County’s concourse is littered with memories of former greats who once donned a Cougars uniform. (Photo courtesy of Casey Drottar)

Ownership set the bar modestly when establishing attendance targets, assuming that getting 100,000 fans through the gates would represent first-year success. Larsen aimed higher. He was convinced that an over-the-top marketing approach could help him dwarf ownership’s sales goals.

Larsen conducted speaking engagements all over town, explaining what the Cougars would represent. He had his group sales staff sell tickets door-to-door. He printed over one million pocket schedules to distribute around the area. Larsen even sent mascots down to CTA stations in Chicago, having them spend entire days on the train solely to ensure schedules went out to as many riders as possible.

Determined to go beyond guerilla marketing, Larsen spent $100,000 on 10-second ad space with WGN Radio. As a then-affiliate of the Baltimore Orioles, advertising with the flagship station of the Cubs seemed unconventional, even to Larsen’s staff.

“I was like ‘Bill you’re going to spend that much money from our advertising budget?’’’ Lane said. “It was unheard of at the time. And it worked. That really blew my mind.”

Said Larsen: “Everything we did was to an extreme. I knew the way I was doing things promotionally was better than anybody else, even in Chicago. I’m putting all my cards on the table. I’ll sink or swim on what I believe in.”

He didn’t sink.

In the Cougars’ debut season, they brought in 240,290 fans, outdrawing all but one of the 13 other clubs in the Midwest League. They broke the league’s single-season attendance record the following year, then topped it again the season after that. In one six-year stretch, Kane County annually drew over 500,000 fans. Even after the league expanded to 16 clubs in 2010, the Cougars only fell below third in single-season attendance twice.

They didn’t just survive in a major league market. They thrived in it. They were recognized to the point that their schedule was listed alongside those of local pro teams in the sports section of the Chicago Tribune. Their games were sometimes broadcast on WGN Radio, even when they weren’t a Cubs affiliate.

“When I grew up, we didn’t even know what minor league sports were in Chicago,” Haug said. “You get a guy like Bill Larsen to be the Pied Piper and bring all these people into the ballpark? He just put us on the map.”

Larsen eventually departed Kane County in 1997, but still holds deep emotional ties to his former club. To him, its loss of affiliation unraveled years of tireless dedication put into making the team succeed.

“Oh my god, it hurt,” Larsen said. “It hurt a lot. This is my baby, this is where I started. I know what it took to get it to the point where it was. I knew what I had to do, and it worked. I didn’t want to see it go.”

While he and Lane lamented MLB’s decision, Haug and crew had no choice but to move forward. Cougars baseball was returning in 2021, the team just had to figure out exactly how it was going to happen.

Life Unaffiliated – Part 2: “Two Big Punches in the Gut”

Photo by Thomas S./Unsplash | Adapted by Ethan Kaplan (@DJFreddie10 on Twitter and @EthanMKaplanImages on Instagram)