I write about stats a lot. More often than not, anything Going Deep is full of numbers and data. That’s the point! Most of it is pretty cool stuff. It can be fun–and useful–to put a label on some of the things that make any given player unique.

At the same time, sometimes they can’t do it justice, whatever *it* might be. Sometimes, I’m burnt out by the numbers. The pandemic does it to all of us: I’m burned out by the racism, by toxic professional elitism, by umpires caping for would-be dictators, by the needless putting of lives at risk, for the total disinterest in solidarity. I’m burnt out by all the things wrong with baseball. Sometimes, it feels like, the numbers can be a part of what’s wrong with baseball. A few nights ago, I was struck heavily by a brief, but poignant, anecdote given to us by David Maraniss in his biography of Roberto Clemente:

“Some baseball mavens love the sport precisely because of its numbers. They can take the mathematics of a box score and of a year’s worth of statistics and calculate the case for players they consider underrated or overrated and declare who has the most real value to a team. To some skilled practitioners of this science, Clemente comes out very good but not the greatest; he walks too seldom, has too few home runs, steals too few bases. Their perspective is legitimate, but to people who appreciate Clemente this is like chemists trying to explain Van Gogh by analyzing the ingredients of his paint. Clemente was art, not science.”

Oof. With all that being said, I’m going to wax poetic for a while about Nick Madrigal, who is more fun to watch hit than just about any other MLB player I’ve watched in this cursed season. Don’t worry, there will be advanced stats and insights. But that’s not the narrative; I’ll let someone else tell Madrigal’s story through numbers. Just let Maraniss’s words marinate for a second. It’s worth the pause.

…

You don’t need numbers to tell that Madrigal doesn’t fit typical ballplayer molds. It’s natural that stature is the first thing you notice when watching him hit. A visual grab makes his listing at 5’8″ and 175 pounds seen generous. Most fans can probably name the easy comparisons: Altuve, Pedroia, maybe David Fletcher, for the alert west coaster. None of them hit as true one to ones though. Many of his prospect write-ups agree. Baseball is a questionable place for those who don’t resemble anybody else.

There’s a compelling aesthetic to the way Madrigal’s bat finds the ball. The rarity in the game of his physical build is obvious; more importantly, it’s even more obvious that in baseball terms, he’s a pure hitter. The pitcher begins to deliver. His weight shifts back. The hands stay high behind his shoulders. The foot raises off the ground, knee coming up past his bet. The foot lands and the path of the bat seems impossibly short and to the point.

That’s when there is a swing, and when there is, there’s always contact. Eight and a half times out of ten, at least, and that’s without any adjustment to big-league pitching. After a few pitches, it’s like watching cricket. A set of wickets wouldn’t be out of place in lieu of a catcher. He’ll get on base or he won’t, but the batter’s goal is to beat the pitcher, and it’s a remarkable thing, knowing that the pitcher will almost never quite win that battle one on one.

…

The last hit of Nick Madrigal’s college career was a single up the middle.

He stepped to the plate with his team, the third-seeded Oregon State Beavers, nine outs away from advancing to the finals of the College World Series. Five days later, they would in fact win the title in a thrilling three-game series over a mashing Arkansas squad led by future second overall draft pick Heston Kjerstad.

Madrigal would go hitless in 15 championship series plate appearances. His batting average fell thirty points, all the way to .367.

Cole Gordon pitched for Mississippi State. Taking over for staff ace and Pitching Ninja darling Ethan Small, in the fifth inning, Gordon was in the midst of a performance which I hope he rightly considers a hell of a personal accomplishment. Back against the wall, season on the line, ace in the hole played, and he delivered four and one-third innings of scoreless baseball. He allowed just a single hit.

The College World Series is as professional an environment as you’ll find in baseball below the majors. Eduardo Pérez on the call, thousands of visitors to Omaha in the crowd, all the Elias Sports Bureau stats you could ask for, presented on sleek graphics and chyrons usually reserved for the pros. Or at least for football and basketball. If you want to check out the whole game at the at bat, knock yourself out.

Madrigal’s bat–the composite handle, swirling red-and-black graphic wrapping the barrel, thick white lettering faded by a season’s worth of hits and foul balls–is the only indication that what’s happening is on the amateur stage.

On the first pitch, he lays a bunt down the third base line. It goes foul. Madrigal is fast–MLB sprint speed in the 77th percentile, albeit without a “bolt” recorded–and it’s a solid effort. One arrow loosed, zero hits.

He takes the second pitch, a fastball right down the middle. We know how fast it was: 92 miles per hour. Madrigal passes, and on the next two pitches out of the zone. Stepping out of the box every pitch or two, giving a cut-off, three-quarter swing that Pérez comments on. As a hitter, it’s fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice… Madrigal is rarely fooled twice. The next fastball down the middle–92 miles per hour–is fouled off.

Third time doesn’t do the trick for Gordon, either. 92 miles per hour again, inside, and nearly to Madrigal’s chin. This is a Win, for most hitters. Against a pitcher in a groove, you’ll take your chances with a 2-2 count and wheels that make a walk tough to swallow. He swings, keeping his hands in with control and quickness that demonstrates why his stature is a feature, not a bug, of baseball playing ability. The bat meeting the ball doesn’t quite do justice to the unlikelihood of finding a barrel:

Nick Madrigal hit a single up the middle.

Weeks after being selected fourth overall, it’s the last hit he’ll land as an amateur. I don’t know the exit velocity. I don’t know how much spin Gordon’s fastball had on it, or what the hit probability was. On the next pitch, he was caught stealing second base and went back to the dugout. Cadyn Grenier struck out swinging, and that was that.

…

Had things gone a little differently in Omaha that June, he might have run into another first rounder heading to the majors by way of the AL Central. A day before Madrigal rapped the last of 221 hits as a Beaver, Brady Singer walked off the mound for the last time as a Florida Gator. He allowed four runs on six hits in five innings, a valiant effort which nonetheless led to the Arkansas Razorbacks’ meeting with the Beavers.

It was also the second season in a row that the two narrowly avoided crossing paths. In 2017, the roles were reversed: Oregon State would have found the Gators waiting for them had they managed to overcome eventual champions Louisiana State. Three weeks before their near-Nebraska rendezvous, and about 25 minutes after the White Sox popped Madrigal, Singer was taken by the Kansas City Royals with the 18th pick in that same draft.

…

Nick Madrigal hit a single up the middle.

This one is less than a year later, April 16th, 2019 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where the Dash are hosting the Wilmington Blue Rocks. In my view, the Blue Rocks have the superior name and mascot–a blue moose named Rocky Bluewinkle–but that might be reconsidered if Wally Warthog makes a comeback.

Singer is making his third professional start. His first two have been successful, striking out 11 against just two runs in nine and two-thirds innings. 15 months later he’d be in the big leagues, but now, the SEC is much nearer than Kaufman Stadium. Luis Robert is on first base. Not yet called the next Mike Trout by his teammates or the recipient of the largest of the exploitative contracts that have become popular to award to promising (typically Latin American) prospects. Just the team’s dynamic leadoff hitter and here, a runner on first.

They’re both paid professionals, but considering the spectacle that would’ve been had they met in Omaha, the dull afternoon daylight, grainy camera feed, and implications of mid-April baseball make this somehow more intimate. The kind of passiveness that among many other things makes Minor League Baseball a joy also gives the ensuing showdown between Singer and Madrigal a personal quality that doesn’t exist with more than a few thousand spectators present. When everything else is stripped away, there’s just the pitcher and batter, playing baseball.

Before anything actually happens, there’s a pitchout. Catcher MJ Melendez pops up and bluffs a throw. Robert is static. Madrigal is stoic. They’re all fresh-faced and younger than me, and I’m young enough to let this bother me. As Singer prepares to deliver, he has Robert picked off. Ducking, diving, dodging, Robert nearly beats the throw to second and miraculously evades the tag. The manager isn’t on the top step of the dugout with their hands thrown up, looking to the tunnel, ready to say the word that will outsource the decision to New York.

I was completely unaware of all this, as were most of the fans that would be voraciously anticipating the pair’s arrival in Cook County a year and change later.

Finally, Singer pitches to Madrigal. Luis Robert is on second base. It’s a slider, away, two balls and no strikes. This isn’t Omaha, and there’s no radar gun on the screen. Singer’s slider this year has typically been about 84 miles per hour, spinning in the vicinity of 2400 rotations per minute. The data says it’s got better up and down movement than side to side, but this one had enough hook on it to end up in the lefty batter’s box. Oh well.

Hitter’s count, runner in scoring position. Twitchy is the best way I can describe Singer’s quick, hectic motion. I’m looking forward to the day I can get an impression of it up close and personal. Madrigal raises his knee as high as his chest in anticipation, slowly but surely finding the timing on his opponent as he surely has hundreds of times before.

Inside fastball. Almost hits him. 3-0 count. The announcers laud Singer for his control, speculating that Robert’s basepath antics were occupying his attention. If he’s flustered, he’s not wearing it on his face. Strike, fastball away, 3-1. The announcers tell us that it’s 92 miles per hour. Madrigal steps out of the box to take more practice cuts. Dry swings are the same on a Division III field as they are in the minors as they are in the majors. Sometimes I wish we could see the imaginary pitch.

A 3-1 slider finds the zone, and the count is full. Robert dances several strides off second base, looking to grab Singer’s attention in the background of a zoom. Madrigal stares blankly. The pitch looks like a fastball, but it could’ve been a hard changeup. This time, when Madrigal’s foot comes down, the bat comes around with it. Statcast wouldn’t recognize it as a barrel by their definition, but for one sitting down the first base line, I imagine the crack of the bat preempts it. It’s a single, a low hybrid line drive/ground ball up the middle Robert scores. Madrigal gets caught trying to advance to second on the throw. He goes back to the dugout.

…

Another year later, Nick Madrigal hits a single up the middle.

The camera is clearer–full 1080p–and the uniforms are crisper. The announcers are recognizable. Not only is there a radar gun on the screen, if you use the internet, you can know the spin, the exit velocity, and all the stuff you normally read about in this section.

At this point in time, Madrigal has four hits in the major leagues, all coming in a single game. He’s taking practice cuts in the box for the first time in several weeks after separating his shoulder several weeks prior. I’ve wondered in the past what it feels like to step into the box in a major league stadium after some kind of layoff. This year, there are no minor league rehab assignments.

Brady Singer is stepping on the mound in a major league uniform for the seventh time. This is his first visit to Guaranteed Rate Field (I don’t care, it’s still the Cell), and his first go-around with the White Sox after having the misfortune to make three consecutive starts against the Minnesota Twins. My heart goes out.

This time, Luis Robert is on third base. A lot has happened since he worked his way out of a pickle in Wilmington, North Carolina, but the game is the same. They’ve been here before.

Singer is in a bit of a jam. There’s only one out. Madrigal is famous for his ability to not strike out, a pitcher’s best friend in such a situation. Simultaneously, Madrigal is docked for his proclivity to put the ball on the ground, not a desirous trait in the modern game. But with a runner on first and one out, a popout is the pitcher’s backup plan if the strikeout is unavailable. Doesn’t seem likely.

First pitch strike. 94 miles per hour, right down the middle. This ain’t the minors. It spins at exactly 2400 rotations per minute. He tries it again. A touch behind it–foul ball to the right side, hit at just a hair over 84 miles per out. An 0-2 count. Weak contact. Singer is winning. He’s unflappable. He’s won plenty of times before.

By all accounts, the next pitch should have hit Madrigal in the face. Another 94 miles per hour fastball, but somehow the bat is on the ball just as I flinch at a pitch that instinct says got away from the guy who threw it. It’s 3.95 feet from the ground. That’s about 48 inches tall. Nick Madrigal is about 68 inches tall.

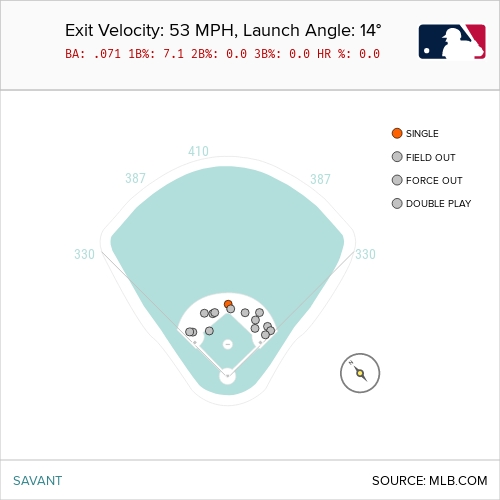

Exit velocity: 53.5 miles per hour. Launch angle: 14 degrees. Hit probability: 7%. What a 7% that is!

Base hit. Luis Robert scores. The White Sox lead 2-0.

Pitchers have thrown plenty of pitches high and inside to righties. At least 3.75 feet up and at least 1 foot from the center of the plate towards the right-handed batter’s box? 1934 of them in 2020, to be exact. Hitters have chosen to swing at just 40 of them. Exactly one of those forty swings resulted in a base hit. Gotta love that 7%!

…

Singer is working. Nomar Mazara stands on first base. The Royals trail 2-1. There are fewer than two outs.

It’s the fifth time in the past six days that he’s been through the White Sox batting order. Two innings earlier, Madrigal brought home two runs with a single up the middle. We can’t quite see Singer’s face. I at home can feel the fluster, though. The pitcher has a job, and that’s to get the hitter out. The hitter has a job, and that’s to beat the pitcher. Sometimes ancillary goals are presented. We can feel the fluster because we have the all-too-familiar sense of a daunting job. It’s a job Singer has done hundreds and thousands of times. Madrigal makes it a bit tougher than most.

On an 0-1 count, Madrigal shows bunt. This time, he doesn’t try to get a hit. He pulls back just as the fastball–91.9 miles per hour, 2202 rotations per minute–crosses the plate at his knees. The umpire doesn’t have the benefit of the box on the tv screen that tells us where they’re supposed to call a strike. Oh well.

Madrigal fakes a bunt, tv analyst Steve Stone explains, to try to bring the third baseman in. In turn, this makes it more likely that a moderately well-hit ground ball finds a hole and gets through. We can’t quite tell whether it works. The camera never cuts to Maikel Franco.

Even count. Advantage? Nobody. Singer has thrown more than a few pitches to Madrigal. Not many of them have gotten the desired results. I imagine Singer knows this as well as anyone in the ballpark. Perhaps he’s filled with the kind of stubborn determination that builds when one repeatedly fails at a task that we know we’re capable of completing. Or maybe not. It could just be another batter, faceless, who hasn’t quite been figured out yet. Maybe for any one of them, most of all we on the other side of the screen, it’s an at-bat in the 4th inning of a close baseball game.

The pitch is a fastball, high and inside. 92 and 2230. Mazara runs with the pitch. We don’t know if it’s a hit and run or if he went of his own accord. Nomar Mazara’s sprint speed is in the 25th percentile. He has seven career steals. It’s all off-camera, and the only indication we have of movement is when catcher Salvador Pérez pops out of his squat to gun the ball to second baseman Nicky Lopez. For a split-second, we’re overcome by the unknown. There are no percentages for this.

The anticipated collision at second base never happens. Pérez’s hand comes up empty; there’s nothing to throw. The pitch isn’t quite as high or inside as the jam shot a few days prior. It just makes it easier for Madrigal. The quickness and precision of the bat is never any less remarkable. It’s not a Statcast barrel, but it catches the good part of the bat nonetheless. Exit velocity: 86.3 miles per hour. Launch angle: 15 degrees. Hit probability: 98%. Run: scored. Madrigal: 3. Singer: 2.

Barring trades, injuries, and other unfortunate, unexpected occurrences, Madrigal and Singer both have a good five years left to trade off between Kaufman Stadium and GRF. The numbers tell us that Singer’s strikeouts will only go so high and far in the big leagues. So be it. Nick Madrigal’s average exit velocity might never break 86 miles per hour. I don’t think the South Side minds.

(Photo by Zach Bolinger/Icon Sportswire)

Just plain enjoyable to read