As all fans know by now, MLB owners have locked out the players while both sides – the owners and the MLB Players Association – attempt to hammer out a new collective bargaining agreement. With each passing day, those of us who long for the return of America’s Pastime are left frustrated, and our minds can’t help but wander when it comes to what on-the-field changes might be included in the new CBA.

These potential changes could have significant fantasy baseball implications. A universal designated-hitter, for example, might provide a massive fantasy boost to a player like J.D. Davis. At the same time, such a change would raise the ERAs and WHIPs of most National League pitchers. While the universal DH is one of the more talked about potential changes, there are others that could come with the new CBA that would alter the value of particular players. One such change would be banning the shift.

Why is the shift on the hot seat?

Since taking over as Commissioner of MLB, Rob Manfred has not minced his words when it comes to the shift. In response to the idea of injecting more offense into the game during an interview with ESPN’s Karl Ravech, Manfred stated, “… things like eliminating shifts — I would be open to those sorts of ideas.”

In 2020, during an interview with Dan Patrick, he said, “A lot of people feel that the extreme shifting … has changed the game in ways that are not positive…”

As recently as the 2021 All-Star Game, Manfred was quoted saying, “I think front offices, in general, believe [banning the shift] would have a positive effect on the play [of] the game. So, you know, I’m hopeful [that it will happen].”

Manfred’s crusade to end the shift is coming to a climax. Should he be successful, there will be significant consequences for certain hitters (particularly pull-heavy hitters), and the professional hurlers who have to pitch to them.

How is a “shift” defined?

This is an important question not only for the data that is to come in this article, but also for MLB if it plans on making significant rule changes that need to be put in writing.

MLB.com defines “shift” as, “… a term used to describe the situational defensive realignment of fielders away from their ‘traditional’ starting points.”

Building off from that basic definition, it gets more specific by acknowledging two separate categories of infield shifts: “Three (or more) IF on One Side of 2B” and “Strategic Positioning.”

Having three infielders on one side of second base is the most common form of shifting. Here is an example of this style of shift turning what would have been a a base hit for Oswaldo Arcia into a double play:

MLB.com defines strategic positioning as, “our current catch-all for positioning that is neither ’standard,’ nor ‘three infielders to one side of second base.'” An example of an infield strategic shift could be that, in an otherwise standard-looking infield, the second baseman is playing in short right field.

Drastic shifts in the outfield where players are way out of position are rare. Outfield strategic shifts, though, are quite common. Still, it is tough to envision MLB banning a centerfielder from shading a bit to his right, or an entire outfield backing up to keep a ball in front of them when the situation warrants it, for example. So, this article’s attention will be focused on infield shifts and their potential banning.

FanGraphs uses slightly different definitions of “shift.” They use the definitions that Baseball Info Solutions came up with in which shifts are broken up into two categories: “Traditional” and “Non-Traditional” shifts.

Traditional Shifts:

1) If there are 3 infielders playing on one side of the infield, we consider that a Full Ted Williams Shift.

2) If two players are positioned significantly out of their normal position, we consider that a Partial Ted Williams Shift.

3) If one infielder is playing deep into the outfield (Usually the 2B 10+ feet out into right field), we consider that a Partial Ted Williams Shift. If the 2B is only a few steps into the outfield, that does not count.

Non-traditional shifts are situational shifts not covered under the definition of traditional shifts.

On the surface, they certainly read differently, but ultimately it would seem that a “traditional shift” to FanGraphs is essentially both categories of infield shifts that MLB.com gives us – “Three (or more) IF on One Side of 2B” and “Strategic Positioning” – combined into one category.

For the sake of this article, I am going to be using two sources – FanGraphs and Baseball Savant. With that said, I am going to lean on FanGraphs a little more. This is important to keep in mind as we dive into the data because the different definitions on both sites may lead to some noticeable differences. For example, if filtering FanGraphs leaderboard splits for batters facing the traditional shift, one would find that Anthony Rizzo had 344 plate appearances against the traditional shift, posting a .252 wOBA in those PA. Baseball Savant (MLB.com), on the other hand, tells us that Rizzo faced the shift in 438 PA and posted a .340 wOBA.

The difference in PA and wOBA between the two sites is due to their differing definitions of what constitutes a shift, as well as the fact that FanGraphs is only accounting for non-home run batted balls. Since walks, strikeouts, and home runs don’t help us understand how the shift impacts a hitters ability to get on base, I like FanGraphs’ data more for this research.

If the shift is banned, who stands to benefit and how do we know?

According to Baseball Savant, there were 180,199 total plate appearances during the 2021 season. Of those PA, 30.9% (55,595 PA) faced a shift in which three (or more) infielders were on one side of second base.

The majority of those 55,595 PA were made up of left-handed batters (38,200). Lefties have always been shifted significantly more than righties since this data started being tracked on Savant in 2016, but never in a full 162-game season had they been shifted against in more than 50% of their PA. That was, of course, until 2021 when 52.5% of all LHB PA were against shifts. That is a lot of shifting!

Considering about one-third of all PA in 2021 faced a shift, it is hard to ignore the potential impact a banning of the shift could have on offenses around the league. Most MLB teams and the people that work for them are smart. If they are shifting, it is because they believe it gives them a better chance at recording an out than a traditional fielding approach would – obviously. So, we can perhaps assume that banning the shift would be a boost to offenses around the league.

This may not be true for every player. Some hitters in 2021 appeared unaffected by the shift.

Take Adam Duvall, for example. In Duvall’s 554 PA in 2021, he faced a shift in 315 of them (56.9% of his total PA). Within that chunky sample size, Duvall had a .337 wOBA (unfortunately, Baseball Savant only provides wOBA results on its shift page). For reference, the league average wOBA in 2021 was .314. When facing a traditionally set defense in the other 239 PA, Duvall’s wOBA dropped to .308. He was better against the shift!

But, was he actually? If we use FanGraphs’ data to filter out the walks and home runs, Duvall’s 2021 wOBA against the shift drops to a much worse .259. In truth, he was much better when not being shifted against.

So, who could actually see a real boost to their fantasy value if the shift is banned?

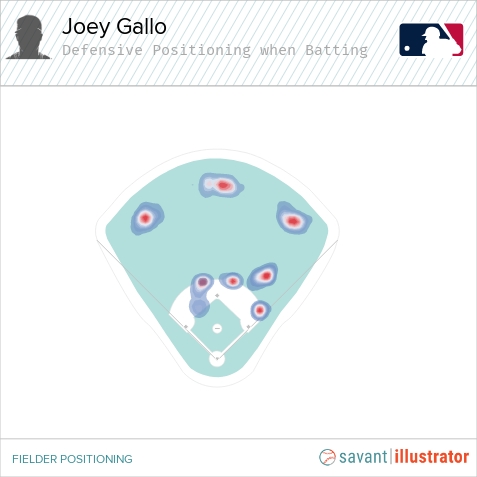

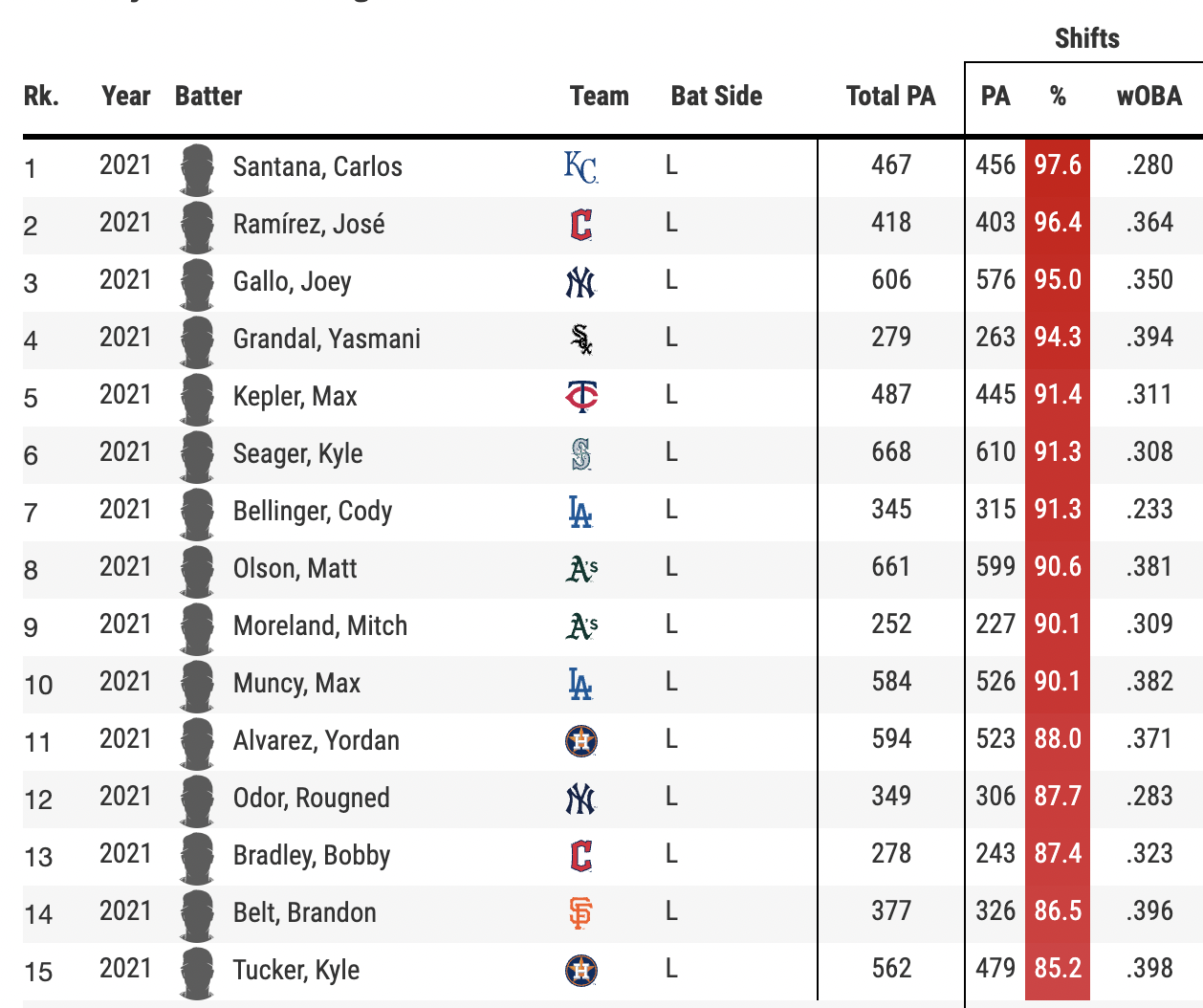

Joey Gallo and Matt Olson both faced the shift in over 90% of their entire PA in 2021. Clearly, opposing teams think they’re having more success shifting these hitters than not shifting them. It is safe to say these two would be better without having to face the shift. However, that is tough to quantify with data when their numbers against non-shifted defenses are based on tiny sample sizes (30 ’21 PA for Gallo, 62 for Olson), even though we know it to be true. Why else would opposing defenses essentially never have a third baseman when facing Gallo unless there are men on base?

To make it simple: players who are extreme pull hitters, and also get shifted against often, are probably going to see something of a boost to their numbers if the shift gets banned. Much like Olson and Gallo, the value of players like Kyle Tucker and Brandon Lowe, who both faced a shift in over 78% of their total PA, would increase. You probably didn’t need this article to tell you that.

What about the not-so-obvious options, though? Could some players see a boost to their numbers if the shift is outright banned other than the typical pull-heavy lefties who face a shift in the overwhelming majority of their PA? To answer that, I dug into the 2021 numbers.

Here are some notable players from 2021 who…

- Faced the shift in 30%-65% of their total PA (this keeps the non-shifted PA at a reasonable sample size of 35%-70% of their total PA)

- Saw an increase in batting average on balls in play (BABIP) against non-shifted defenses when compared to shifted defenses

- Had at least 450 total PA in 2021

While some of these names might excite you should the shift get banned, this data does not come without a key flaw: sample size. The chart is only looking at one season’s worth of plate appearances and is breaking that one season’s worth of plate appearances up into two separate categories. When you then factor in that walks, strikeouts, and home runs are removed from these two separate samples, they get even smaller. So, for example, that .340 BABIP vs No Shift that Springer posted was only based on just 50 PA. Happ’s was based on 74 PA and Conforto’s based on just 36 PA. Every other BABIP listed in the table is based on at least 100 PA. Even still, that is a pretty low bar to set in terms of sample size. I would expect their BABIPs to go up if the shift is banned, regardless of the small samples, but perhaps temper expectations. The boost in production may not be as significant as the chart might suggest.

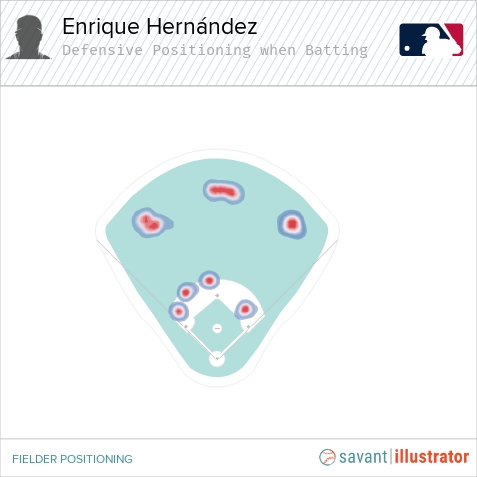

To make matters even more unclear, if we looked at the same numbers but from the 2019 season (skipping over 2020 for the sake of sample size), players like Hernández and Conforto had significantly higher BABIPs against the shift than against no shift. Do we put stock in 2019? 2021? Neither?

The much rarer RHB shift. Hernández had a Pull% of 42.5% in 2021

Even if the shift is banned, and even if that helps a player like Hernández, it is tough to get too excited considering he only faced the shift in 31.4% of his PA in 2021 – enough to qualify for this exercise but is it enough to have real fantasy implications? I’m not so sure. So while the table above is interesting – especially when realizing that Pérez and Haniger could have had even better seasons if the shift was banned in 2021 – it does not paint a complete picture.

Rather than players who faced the shift on an inconsistent basis, I think the bulk of your attention in drafts, as it pertains to potential no-shift-implications, should be on those players who face the shift just about every single time they step to the plate. While players like Happ and Grisham do get more interesting if the shift is banned, many of the players listed in the Savant chart below have the highest likelihood of seeing a boost – big or small – to their numbers given the extreme amount of times they have had to face a shifted defense in the past:

None of those names should really be all that surprising. They are all high-pull% LHB. It makes sense that they face the shift a lot. Ban the extra defender that gets to play in the area where a batter hits most of his balls, and you should see a natural uptick in that batter’s BABIP. It won’t all of a sudden make Gallo a .300 hitter, and it most likely won’t lift Brandon Belt from his platoon status, but it certainly will make a difference.

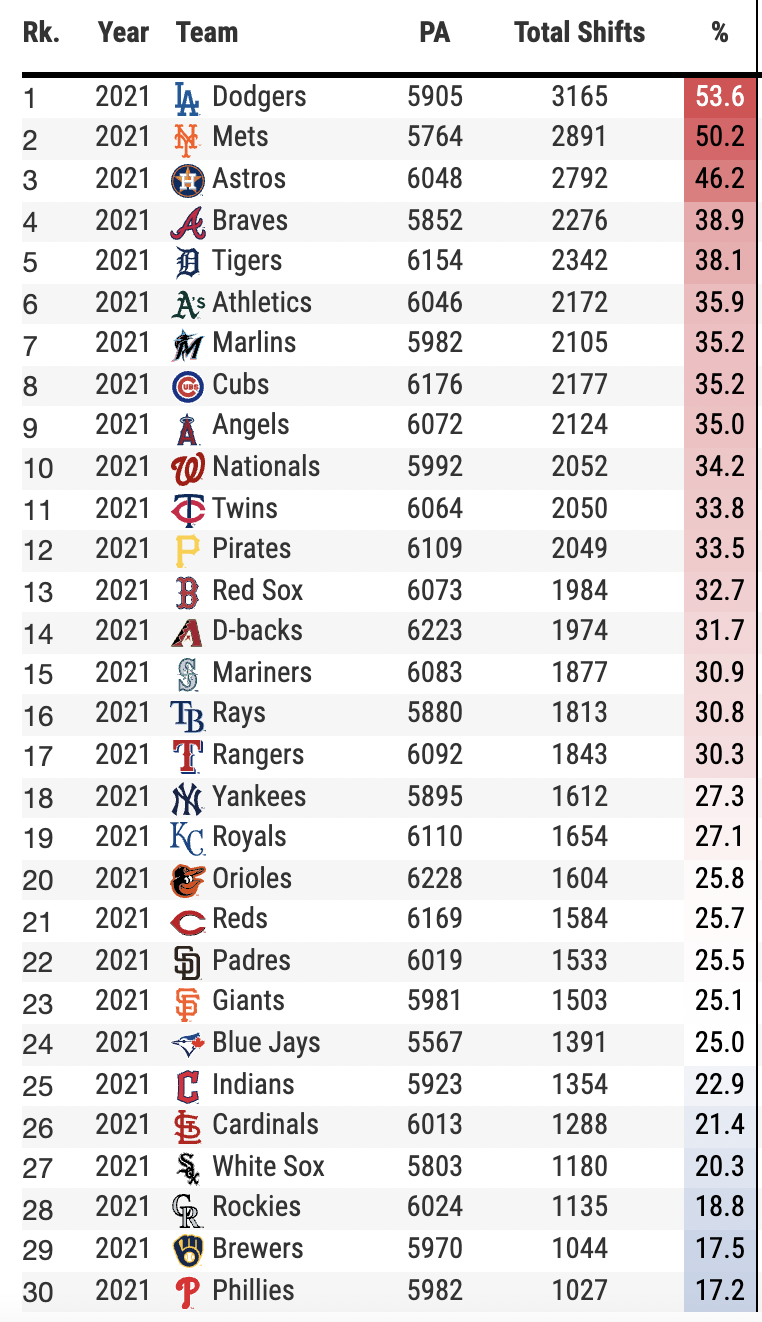

What about the pitchers?

Well, if offense as a whole will go up because of a ban of the shift, then of course pitching will go down a bit. I don’t think there is a way to know just how much worse it would get until we have multiple seasons worth of data. With that said, the Dodgers, Astros, and Mets shifted significantly more than the rest of the league in 2021, with the Dodgers leading the pack. All three of those teams had team ERAs ranked in the top ten in all of baseball, with, you guessed it, the Dodgers leading the pack. Coincidence or not, a ban of the shift certainly could impact those teams’ pitchers more than others.

Ground ball heavy pitchers figure to be impacted more by this potential change than their fly ball heavy peers, for obvious reasons. After all, infield shifts aren’t really useful if the ball is hit in the air. Yet, there does not seem to be much correlation between pitchers with high GB% and pitchers who had a large portion of their PA with a shift on. Instead, there is a much clearer correlation between teams who like to use the shift a lot and pitchers who had a large portion of their PA with a shift on. For example, despite just a 38.5% GB%, Luis García led all pitchers with at least 500 PA in Shift% (Shifts/PA). The Astros roster three of the top ten in that category: Zack Greinke, Lance McCullers Jr., and García. The Dodgers and Mets also had multiple names in the top ten for Shift%. The shift is a tactic used against specific hitters, not for specific pitchers.

Courtesy of Baseball Savant:

Closing Thoughts

Banning the shift, or at least altering it so that there cannot be more than two infielders on either side of second base, seems to definitely be on the table for the upcoming CBA. The impact this has on specific offensive players in fantasy could be significant, but it would really be on a case-by-case basis. While players like Gallo and Olson would receive more of a fantasy boost than others, there are some names out there who I would keep an eye on as it seems as though the shift was a quiet, but impactful, thorn in their side in 2021.

The league’s BABIP would undoubtedly go up, but the impact that has on individual pitchers would be hard to quantify and would probably prove inconsequential as pitchers don’t have much control over opposing BABIPs to begin with – shift or no shift. With that said, some pitchers on teams that have successfully enacted the shift at a high rate may seem to regress a little bit more than others.

Whether the shift gets banned or not, let’s just hope the league can get its act together so we can start baseball on time.

Featured image by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)