Pablo López has long been an intriguing player. The issue has always been pretty straightforward: for all of his raw potential, López has never missed enough bats to be a projectable strikeout pitcher. I’m sure it’s not difficult to know where I’m going with this. López wasn’t missing a lot of bats, and now he is.

We’re through five starts now, and about a third of the way through the shortened season. Here’s how López has fared by swinging-strike percentage, compared to previous years:

- 2018: 10.4%

- 2019: 10.2%

- 2020: 14.4%

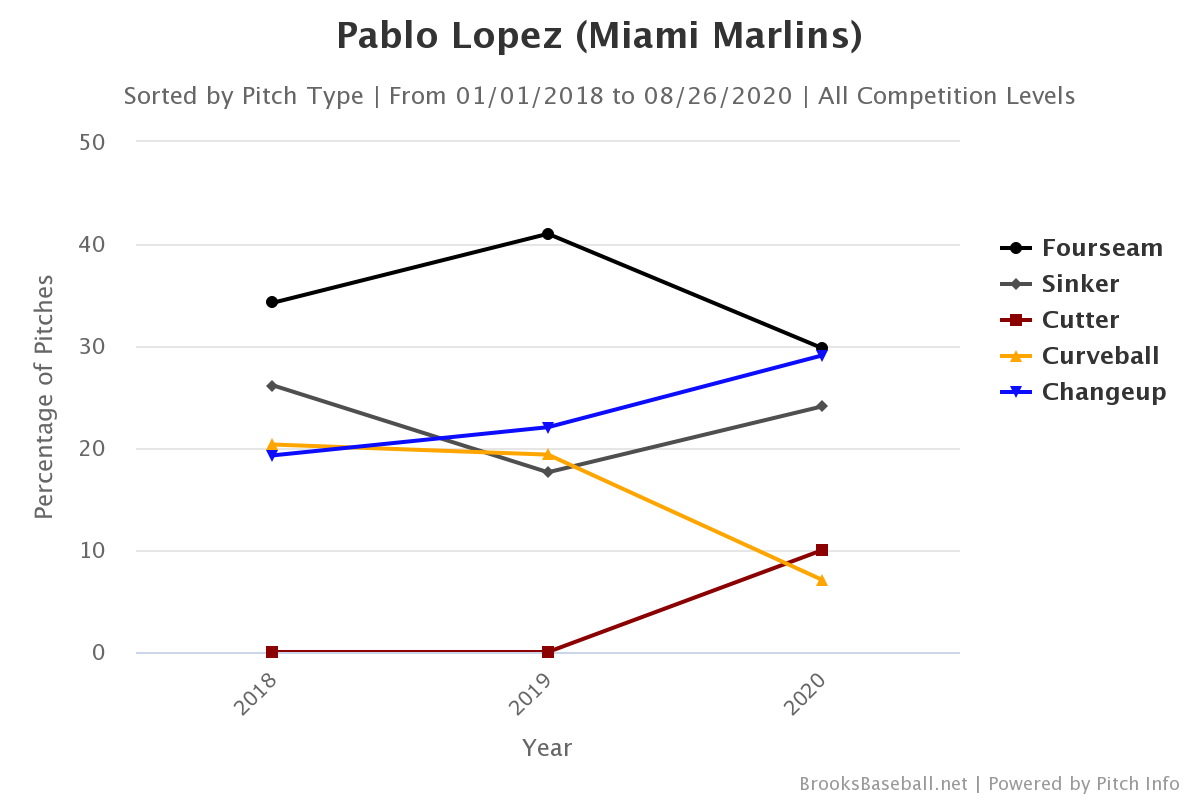

Hitters are swinging more, but they’re making contact less too. Some reasons for this are more obvious than others. López’s pitch mix, by year:

The changeup? It’s a good pitch. That’s why, according to Baseball Savant, he’s throwing it more than either of his fastballs, while Brooks Baseball has him throwing his four-seamer and changeup at about the same rate. In any case, López has bumped up his changeup usage by nearly 10%, and he’s throwing his fastballs (i.e., four-seamers and sinkers) at a lower rate overall. Throw your best pitches more, and your worse pitches less. It’s simple.

For pitchers, something that often gets lost in the weeds is that pitchers approach batters much differently based on the handedness of the batter. That’s certainly not the most revolutionary thing that’s ever been said, but it stands to reason that we should consider how López has changed against lefties, and then righties.

First, a table, looking at some pretty basic statistics, based on handedness:

| K% | BB% | SwStr% | CSW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-9, vRHH | 20.7 | 4.0 | 11.2 | 27.2 |

| 2020, vRHH | 32.1 | 7.5 | 20.0 | 30.0 |

| 2018-9, vLHH | 19.0 | 6.3 | 9.8 | 25.3 |

| 2020, vLHH | 16.1 | 4.8 | 9.9 | 27.3 |

Against righties, López has seen a small uptick in CSW, but the strikeouts are way up, and the walks are up too. He’s traded called strikes for swinging strikes, which is a good trade-off. His zone percentage has dropped more than five percentage points, and it’s all because of his changeup.

López’s changeup, by location:

Not only has he started his changeup more, but he’s also started throwing his changeup lower in the zone too. He’s dropped his zone percentage from 53.0% to 30.4% against righties, and thus far, it’s done wonders for his CSW. We’ll get to this momentarily, but this a fantastic compromise for López. He’s walking more hitters, but the strikeouts easily offset this slight inconvenience — especially given that his overall walk percentage is essentially intact, rising from 5.8% to 6.1%.

Against lefties, it gets a little dicier. Called strikes are good — we know this. But it’s not necessarily an approach that you want to hang your hat on. Given that a fair amount of his strikeouts against lefties are coming on fastballs, I figure it’s appropriate to present a table showing how his fastball is performing.

López’s fastball, by plate discipline metrics, versus lefties:

| Zone% | SwStr% | Called% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 55.8 | 7.5 | 16.5 |

| 2020 | 74.1 | 10.3 | 29.3 |

This doesn’t seem all that sustainable — and most of it probably isn’t — but that’s not to say that López won’t hold some of these improvements. Perhaps something that López may have lacked in the past is a pitch that he can throw hard that moves glove-side. His new cutter could be that pitch — this is something that I’ve deeply considered — but I think it’s more likely that he simply needs to throw his changeup with more conviction.

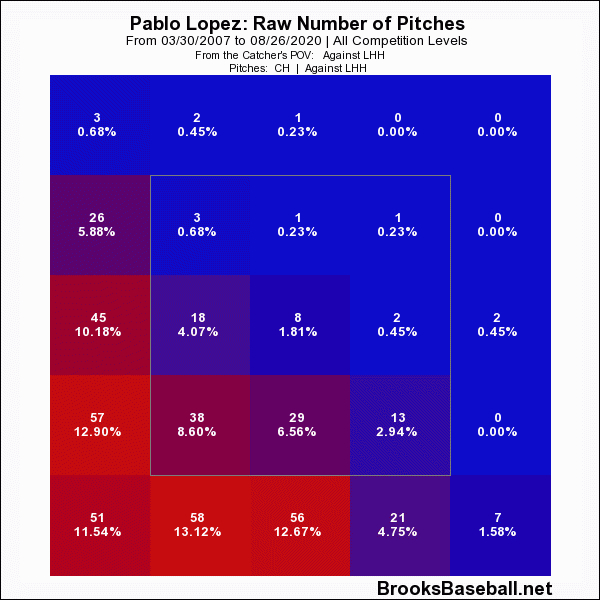

Over his career, here is how López has approached lefties with his changeup:

This looks perfectly reasonable. Not too many hanging around in the zone, and he’s keeping them either to his arm-side off the plate, or below the zone. The thing is, he could be optimizing his changeup a lot better.

Here’s López’s percentage whiffs on his changeup, again, over his career:

López throws his changeup below the zone a lot as is — this is true. But in terms of whiffs, he can pretty much double his percentage by throwing below the zone (outlined in yellow) as opposed to throwing off the plate to his arm-side. This year, he’s doing a great job of keeping his slow ball out of the zone, but he’s leaving them up or too far to his arm-side, whereas the optimal zone remains below the zone.

At this point, we’re really picking nits here. You have to tip your cap to López. He was struggling against lefties, so he took his best pitch and started it more than any of his other pitches. And then he took his worst pitch, and he’s all but stopped throwing it. This certainly bodes well in terms of pitch mix optimization.

Now, to this point, I’ve essentially focused on CSW. That’s because it’s important to throw strikes, and it’s arguably the most significant chance López has made this season. A side effect that’s come with López’s approach this season, though, is that he’s become more of a ground ball pitcher, moving from a career 49.3% ground ball percentage to 61.7% this year.

As Alex Chamberlain has shown, vertical pitch location helps dictate the probability of a pitcher allowing certain launch angles. This is intuitive, to an extent. We know that elevated high-spin fastballs induce a lot of fly balls and pop-ups, and we know that changeups and knuckle curves below the zone induce lots of ground balls. Pitchers may not have as much control over exit velocity as we thought, but they can do something about the angle in which balls are hit, based on pitch location (and to an extent, probably pitch type and pitch characteristics).

We look at heat maps a lot. One thing that we do is look at heat maps at the pitch level, and we do it a lot. But if we think about Chamberlain’s article, we should probably look at heat maps at the macro-level more as well. In this case, we’re considering on the whole, how much has López changed his pitch location?

First, against righties:

And then against lefties:

Against righties, you can see his concentration of pitches is moving ever so slightly lower, and then you can see a few more pitches thrown below the zone. Against lefties, he’s doing a much better job of keeping his pitches away from the heart of the plate, but as alluded to earlier, we’re not seeing as many pitches below the zone as we’d like.

To put it as plainly as possible, López is legitimately improved against righties. Against lefties, it’s more complicated. I think he’s improved here too, but the bulk of his improvements have come in the way of contact management. That may not sound as sexy, but as a pitcher with a .357 xwOBA against lefties last year, I can say it’s a very meaningful development — and there’s still room for plenty of growth.

It’s always felt like this was coming for López. It was just that he never missed enough bats. Now he’s missing more bats, and one of the ripple effects is that when balls do inevitably get put into play, they’re more pitcher-friendly. He may have not completely figured out how to get lefties to swing and miss yet, but once the whiffs come, it’ll be increasingly difficult to argue that there are many holes in the game of Pablo López.

Photo by Mark Goldman/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)

For other pitchers with good stuff but low whiffs (Dustin May, maybe Sixto) does this mean there is hope?

So long as they develop a secondary pitch that they throw more than their fastballs!