The 2019 season was a turning point for the Reds pitching staff after several years in the league’s basement. They lowered their SIERA in a year where the league average jumped by over a third of a run. They went from a net negative contribution to win probability to a net positive, and improved their WAR by over 10 win shares. They did this with, largely, the same staff returning. They retained over half of their innings from the 2018 squad that was in the bottom third of the league in all these metrics, including three of their top five starters (Luis Castillo, Anthony DeSclafani, and Tyler Mahle) and each of their top five relievers (Michael Lorenzen, Raisel Iglesias, Amir Garrett, Jared Hughes, and David Hernandez). These trends continued in the shortened 2020 season and the Reds staff was again one of the best in the league. How did they achieve such a drastic turnaround in such a short time? The answer lies in the organizational change in philosophy brought on by manager David Bell; however, it helps to know a little bit of history first.

Background and History

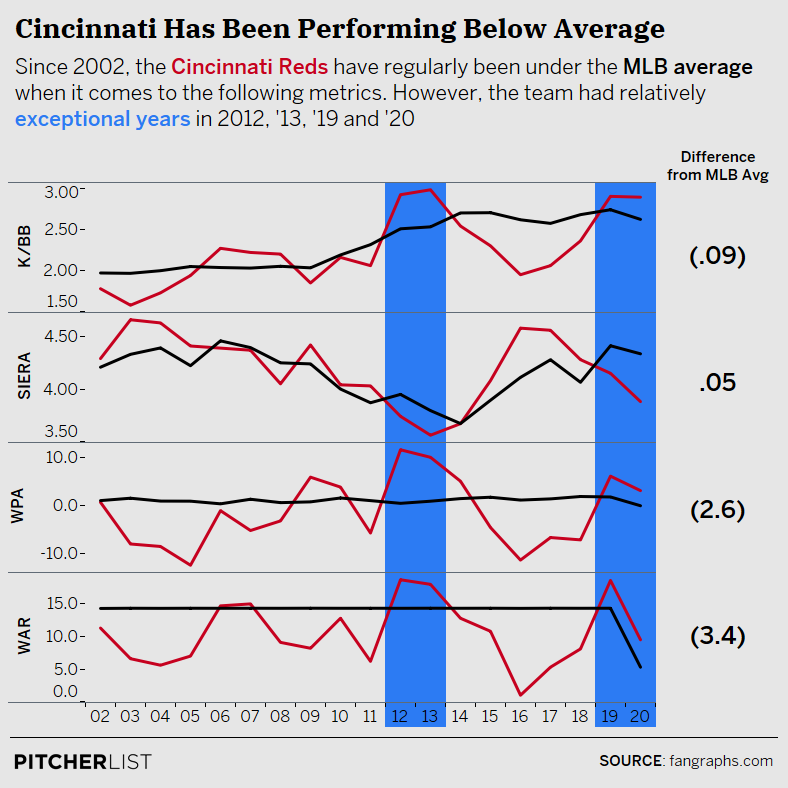

From 2002 up until the beginning of the 2019 season, the Reds’ pitching staff was perennially among the worst in the league. Across all 17 seasons combined they were 27th in WPA, 30th in WAR (Fangraphs), 24th in SIERA, and 23rd in K/BB. The below charts show a season-by-season picture of the Reds’ performance as a staff across these four metrics:

This paints a picture of an organization that struggled overall to field even an average pitching staff over the past 20 years. The WAR chart in particular shows how even an average season by MLB standards was a great achievement for the Reds. They averaged three fewer win shares per season than the rest of the league and put up just 1 WAR in 2016, the lowest mark since the 2006 Royals excluding the shortened 2020 season. However, there are a couple bright spots here: 2019-20 (the focus of this article) and 2012-13.

The 2012 and 2013 rosters were filled with talents like Johnny Cueto, Mike Leake, Homer Bailey, and Aroldis Chapman that the Reds were successfully able to develop in-house. The staff was rounded out with a blockbuster trade for Mat Latos and a separate trade for setup man Sean Marshall before the 2012 season that showed the Reds were ready to compete now and invest in their pitching staff. The staff combined to rank 3rd in SIERA, 2nd in K/BB, 4th in WAR, and 1st in WPA in the two combined years, However, injuries, regression, and money got in the way. After a middling 2014 season, the Reds traded Mat Latos citing payroll concerns. Over the next year and a half, the team proceeded to trade away Johnny Cueto, Mike Leake, and Aroldis Chapman and lost Homer Bailey to Tommy John surgery.

The Reds farm system just couldn’t keep up and, by 2016, the staff had become one of the worst in the league. From 2016 to 2018, the Reds were 28th in K/BB, 26th in SIERA, 30th in WAR, and 30th in WPA with quite a considerable gap between themselves and the next closest organization in both WAR and WPA. Young players weren’t developing fast enough to replace the mass exodus of veteran talent and, just 18 games into the 2018 season, the Reds fired then-manager Bryan Price. After the season, the Reds decided to take a risk and give the reigns of the club over to a man with no MLB managerial experience, but with considerable experience in player development: David Bell.

At the time of the hire, Bell was the Vice President of Player Development for the San Francisco Giants, but he had also spent time in the minor league systems of the Cubs, Cardinals, and Reds. He was valued for his modern approach to player development, a reputation that earned him more than one interview for big league managerial roles in the 2018-19 offseason. During his tenure with the Giants, he told Henry Schulman of the San Francisco Chronicle:

“There’s incredible information, and it has to factor into everything we do… If we don’t access, utilize and implement that information, we’re going to fall behind.”

Like he did in San Francisco, he drove home this commitment to modernization with a slew of new hires at all levels of the Reds organization, the most notable of which was the hire of Kyle Boddy as Director of Pitching Initiatives. Boddy is the founder of Driveline Baseball, an organization which claims to have “The world’s best data-driven player development program” and was a highly sought after name during the 2019 season. Even Boddy was impressed by Bell’s commitment to institutional change focused on modernizing player development. He said in a quote from this article from Jeff Wallner at WCPO Cincinnati:

“There wasn’t anybody close to the Reds in terms of progressiveness… David Bell is unbelievable. It’s amazing how involved he is with staff development on a consistent message from the top to the bottom. A big part of my interview was David Bell. Not a single other organization had the manager call me and not just try to sell me on it—he was involved from day one.”

Bell had a vision and he was making sure that it was reflected at every level of the organization. So, how did this shift in philosophy manifest itself on the field? Let’s look at the player-by-player development from 2018 to 2020 to look for common threads. We will start with those who started as in-house prospects: Luis Castillo, Anthony Desclafani, and Tyler Mahle, but we’ll then also look at a couple pitchers who came to Cincinnati as established veterans: Sonny Gray and Trevor Bauer. Once we have a solid idea of the changes Bell has been able to implement, we’ll take a look at who might break out next from this budding pitcher development powerhouse.

Luis Castillo broke out in the 2019 season, but this breakout continued in 2020 and he is largely considered to be the co-ace of the staff along with Sonny Gray heading into 2021. On the surface, it looks like he achieved a lot of this improvement by doing two things. First, he simply threw his best pitch, the changeup, more. Second, he significantly improved the effectiveness of both his four-seamer and slider. How did his four-seam fastball get so much more effective? Let’s take a look under the hood:

| LUIS CASTILLO’S PROGRESSION 2018 TO 2020 | |||||||

| FB Velocity | FB Spin Rate | High Fastball % | FB SwStr% | Slider Velocity | Slider Spin | Slider SwStr% | |

| 2018 | 95.8 | 2200 | 18.2 | 8.6 | 83.6 | 2206 | 16.3 |

| 2019 | 96.4 | 2170 | 21.8 | 10.0 | 85.9 | 2330 | 20.4 |

| 2020 | 97.4 | 2188 | 33.7 | 17.3 | 86.8 | 2489 | 16.2 |

Note: I am defining “high” fastballs as fastballs thrown in zones 1, 2, 3, 11, 12, and 13 in Statcast’s Attack Zones breakdown.

We can see that a velocity bump explains a decent chunk of the increase in production. Faster pitches are harder to hit; it’s as simple as that. His fastball’s spin didn’t change, so it didn’t necessarily have more life on it, however Castillo began throwing it higher in the zone, the benefits of which are starting to be recognized around the league as explained in this Fangraphs article. One insight in particular I want to pick up from that article is this image that shows us that a 96mph fastball right down the middle (typically 2.5 feet) generates half the swinging strikes as a 98mph fastball thrown just 6 inches higher (10% vs 20%). Castillo made some small improvements in velocity and threw a few more high fastballs in 2019, so we saw a small increase in swinging strikes. Another tick on the radar gun and a considerable jump in number of high fastballs led to a considerable jump in swinging strikes on the fastball in 2020.

We also see the velocity increase reflected in a harder slider. Here, though, the spin did increase which would make me expect a nice jump in swinging strikes as well. We did see that in 2019, but it didn’t hold in 2020 for one reason or another even though the slider continued to gain velocity and spin. Even though those slider improvements didn’t consistently lead to a higher swinging strike percentages, we still have a couple of things to look out for as we dive into other pitchers. First, we saw average velocity improvements on almost all his pitches. Second, we saw his four-seamer used higher in the zone on average. Finally, we saw the spin rate on his breaking pitch improve. Let’s compare those results to our next in-house prospect.

Anthony DeSclafani had an injury-filled and overall disappointing 2020. With only 33 innings logged on the season, I am not leaning very hard on the 2020 stats in my analysis. I feel this ends up giving us more reliable data to base decisions on. Let’s see what it gives us:

| ANTHONY DESCLAFANI’S PROGRESSION 2018 TO 2020 | |||||||

| FB Velocity | FB Spin | High FB % | FB SwStr% | Curve Spin Rate | Curve Usage % | Curve SwStr% | |

| 2018 | 93.5 | 2199 | 21.1 | 6.2 | 1684 | 3.6 | 9.4% |

| 2019 | 94.7 | 2249 | 27.2 | 9.7 | 2048 | 15.1 | 15.1% |

| 2020 | 94.8 | 2225 | 38.4 | 9.9 | 1801 | 10.1 | 3.3 |

We again see a healthy bump in fastball velocity and high fastball percentage, leading to an increase in swinging strike rate on the fastball. The changes are less pronounced here likely because DeSclafani’s breakout was less pronounced. He had already had some success prior to 2018, so 2019 was less of a breakout and more of a return to form for him. What’s more interesting to me is that we also see the emergence of an improved curveball in 2019. I don’t think I can overstate how bad his curveball was in 2018. He threw it just 64 times all year and generated just six swings and misses while allowing six extra base hits and an expected slugging of .967.

I think pretty much any organization in the league would just tell him to scrap that pitch, but not the Reds. They told him to throw it MORE. The rate of improvement is remarkable here as Desclafani added 364 rpm and three ticks of velocity on his curve in just one offseason. The results reflect the improvement in the pitch’s quality as the expected slugging dropped to just .281 and the swinging strike rate jumped up as you see above. The Reds somehow succeeded at turning DeSclafani’s terrible 2018 curveball into a decent offering in the span of just one offseason. Even though there wasn’t a true breakout here in terms of overall performance and even though the curveball never became a truly dominant pitch for him, the velocity bump on his fastball and spin rate improvement on his curveball reflect some of the same improvements we saw in Luis Castillo earlier. Let’s see if we can go three for three.

Tyler Mahle took until the 2020 season to truly break out, but he did it in a big way sporting a 3.59 ERA and a 30% K rate. Let’s take a look at what he changed to improve, do we see another improvement in fastball velocity?

| TYLER MAHLE’S PROGRESSION 2018 TO 2020 | |||||||

| FB Velocity | FB Spin | High FB % | FB SwStr% | Slider Velocity | Slider Spin | Slider SwStr% | |

| 2018 | 92.4 | 2138 | 29.7 | 10.8 | 83.3 | 2511 | 14.9 |

| 2019 | 93.3 | 2161 | 29.1 | 9.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2020 | 93.9 | 2389 | 30.1 | 14.3 | 86.9 | 2635 | 19.6 |

Ding, ding, ding, three for three in velocity bumps. Why did it take Mahle until 2020 to break out when we saw several other pitchers do so in 2019 after just one offseason in David Bell’s program? First, Mahle didn’t succeed in adding spin to his fastball until 2020 and it was this extra movement, fueled also by an improvement in active spin, that made it a more effective pitch. He didn’t need to throw more high fastballs because he was already doing it. Nearly 30% of his fastballs were thrown in the aforementioned high zones in 2018 while Castillo and Desclafani were closer to 20%.

Second, it wasn’t until 2020 until he found a truly effective secondary pitch in his slider. Again, we see the Reds training program able to pull an extra 1.5 mph out of the average fastball and increase the swinging strike rate on the four-seamer. But also, we see another example of how they were able to take a breaking pitch and completely reinvent it. In terms of results in 2018, Mahle’s slider wasn’t DeSclafani curveball levels of bad, but it still wasn’t good. Opponents hit .304 against it and slugged .557. In 2020, opponents hit .180 against it and slugged .361 in addition to the swinging strike increase you see above. After looking at the three younger pitchers that went through the Reds’ new development system, we can see three main points that they all improved on:

- Fastball velocity

- Breaking ball spin rate

- Overall K-rate

I see a lot of evidence so far that the Reds modernized training program implemented in the 2018-19 offseason allowed pitchers to make strength gains and spin gains to improve the quality of their pitches. Over and above that, however, I see a modernized organizational philosophy that helped them place their pitches in spots more likely to generate swings and misses and adjust pitch mixes with an eye on strikeouts. But, will we see similar improvements from established veterans who came to Cincinnati?

Sonny Gray came to the Reds from the Yankees in January 2019 after a somewhat disappointing season in the Bronx. Gray delivered arguably the best season of his career in his first with the Reds in 2019 and continued his strong performance in 2020. We don’t see the same velocity bump that we saw from the previous three pitchers, but we do see some interesting things in his other pitches.

| SONNY GRAY SPIN IMPROVEMENTS 2018 VS 2020 | ||||||

| Slider Spin | Slider SwStr% | Curve Spin | Curve SwStr% | Sinker Spin | Sinker SwStr% | |

| 2018 | 2710 | 18.5 | 2852 | 15.2 | 2310 | 6.7 |

| 2019 | 2868 | 19.3 | 2988 | 11.9 | 2441 | 10.4 |

| 2020 | 2824 | 21.7 | 2954 | 12.7 | 2420 | 11.9 |

We see spin improvements of 100+ revolutions across the board which is consistent with improvements we saw in breaking pitches from the three younger pitchers earlier. However, there isn’t one pitch that jumps out as the reason for a jump from a 21% K-rate in 2018 to 29% in 2019 and 31% in 2020. We do see a sizable increase in swinging strikes on the sinker, but that just doesn’t feel like enough as he threw it just 20% of the time in 2019. In the case of the curveball and four seamer, swinging strikes actually go down. Gray’s overall swinging strike rate in 2019 and 2020 (11.3%) wasn’t tangibly different from his Yankees tenure (10.6%). Generally, these two numbers are very strongly correlated, so it’s strange to see a jump in one that isn’t followed by the other. 8% is nothing to sneeze at either. Just to give you a sense of the scale, Gray would have had 56 fewer strikeouts in 2019 if he had carried his 2018 K-rate over. That 8% improvement in K-rate corresponded to 36% more strikeouts. It’s considerably more than what could be explained by randomness or opponent quality, although it’s worth noting that moving from the AL East to the NL Central definitely helped Gray a bit.

Another piece of the puzzle is captured by called strikes. In 2018, just 18 of Gray’s 123 strikeouts (14.6%) were of the looking variety. For reference, 118 out of 126 pitchers with at least 100 strikeouts that year got a higher rate of called punchouts than Gray. In 2019, he got 49 out of 205 (23.9%) looking, moving him closer to the middle of the pack in the majors in terms of rate. In 2020, his rate of called strike 3s took another jump and he got 28 of his 72 victims looking (38.9%), putting him 4th in all of baseball among pitchers with at least 50 Ks on the shortened year. We should acknowledge here that called strike 3s are considerably more noisy than swinging strike 3s because they rely on another party, the umpire, to call them correctly. The shortened season allowed typically noisy numbers to be even noisier than normal, so that could be playing a role here.

Unfortunately, there’s no clear answer as to why Sonny Gray’s K-rate jumped so much in his move to Cincinnati. There’s some combination of opponent quality, called strikes, and pitch mix with two strikes going on here, but the relative importance of each is not immediately apparent. It’s also not apparent what Gray is doing to generate so many more called strike 3s or if there’s some other important factor that I’m missing entirely. A question like this that doesn’t have an immediate answer that jumps out likely deserves its own article. I’m afraid I’ll just have to settle for the answer “it was a lot of little improvements” for now and leave the details for later. What’s important within the scope of this article is that we didn’t see a velocity increase like we saw with other pitchers, but we did see spin rate increases and overall more strikeouts versus pre-David Bell years. Now, on to the elephant in the room.

I don’t want to talk too much about Trevor Bauer since he’s already been talked about twice this year here on Pitcher List—once by Michael Ajeto and once by Zach Hayes—and a myriad of times on other sites. But, here are the infamous spin improvements:

| TREVOR BAUER SPIN IMPROVEMENTS 2019 VS 2020 | ||||

| FB Spin | Curve Spin | Slider Spin | Cutter Spin | |

| 2019 | 2412 | 2549 | 2736 | 2640 |

| 2020 | 2776 | 2933 | 2941 | 2908 |

A lot has been said about where these spin improvements came from, but is it possible that we just saw a perfect storm of a pitcher on the forefront of data-driven training and an organization committed to supporting pitchers in such training? We consistently saw other pitchers achieving 100+ revolution increases and DeSclafani even gained 364 rpm on his curve over just one offseason. Regardless of how likely you believe that is, though, Bauer achieved a new level of effectiveness in 2020, in some ways even more so than his 2018 breakout. His strikeout percentage rose to 36% from 31% in 2018; however, like Sonny Gray, this improvement didn’t come from an improvement in swinging strike rate or fastball velocity. He is quite an outlier, so I don’t want his case to affect my overall analysis of the Reds organizational approach to pitching too much, but I do want to put up a side by side of Trevor Bauer in Cincinnati before an offseason with David Bell and after:

| TREVOR BAUER AS A RED 2019 VS 2020 | ||||||

| GS | IP | ERA | WHIP | K% | SIERA | |

| 2019 | 10 | 56.1 | 6.39 | 1.35 | 27.5 | 4.06 |

| 2020 | 11 | 73 | 1.73 | .79 | 36 | 2.94 |

Is it a small sample size? Yes. Is the validity of one of the data sets questionable? Yes, again. But, it’s still fun to look at, no?

Who’s Next?

So, what are the inputs and outputs of the Big Red Pitching Machine that we can see? The inputs as I see them are:

- An improved training program allowing pitchers to throw their fastballs faster and spin their breaking balls more

- An increased focus on swings and misses fueled primarily by throwing fastballs higher in the zone

- Using data-driven decision making to tweak individual pitch mixes and the placement and usage of secondary pitches

And the results of these changes in training and philosophy have been:

- Of the Reds top six pitchers by innings pitched in 2019 and 2020, four have increased their average fastball velocity by one to two mph since 2018

- Of the same group, five have improved their spin rate on breaking balls (either a curve or a slider) by at least 100 rpm since 2018

- Swinging strikes and strikeouts increased dramatically from 2018 to 2019 with largely the same players and those improvements stuck in 2020

- Team pitching WAR rose from 8.1 in 2018 to 18.6 in 2019 and was 3rd in the league in the shortened 2020 season

It’s clear to me that David Bell has implemented a training program and pitching philosophy that has brought the Reds pitching staff into the 21st century and, furthermore, placed them at the forefront of data-driven decision making in baseball. Pitchers who spent an offseason being processed by the BRPM (Big Red Pitching Machine) saw consistent improvements in velocity, spin, strikeouts, and overall performance. While in-house prospects and established veterans achieved these results in slightly different ways, the results remained the same. The Reds have gotten the best out of their pitching staff the past couple years. The next question is: Who could be the next breakout Reds starter? There are two main options, as I see them, for 2021: Tejay Antone and Michael Lorenzen.

Going into the 2020 season, one could be forgiven for having no idea who Tejay Antone was. A fringe prospect who was often left off of organizational top 10 lists, he wasn’t exactly a household name. However, he broke out in 2020 in a way that few expected finishing with a 2.80 ERA and 45 strikeouts in 35.1 innings including four starts. How did he achieve this? First, let’s take a look at Antone’s scouting report from just before the 2020 season from redsminorleagues.com:

Fastball | The pitch has good movement on both planes, working in the 89-92 MPH range and tops out around 95.

Curveball | An average to above-average offering that works in the mid-70’s.

Slider | A pitch that improved throughout the year and is now an average to above-average offering.

Looks like a command-first guy who doesn’t necessarily have dominant stuff. Nothing too exciting. Let’s look at what actually happened.

| TEJAY ANTONE’S 2020 SEASON | ||||||

| Average FB Velocity | FB Spin Percentile | Curve Spin Percentile | Slider CSW | Curve xwOBA | K% | xERA |

| 95.6 | 98 | 95 | 45.2 | .118 | 31.9 | 2.99 |

Let’s take a moment to absorb these results. His fastball didn’t top out around 95. It AVERAGED over 95 and topped out around 98. I saw some sources say he added as many as four mph to his fastball in a single offseason. That slider CSW of 45.2 places him second in all of baseball to Yu Darvish among sliders that were thrown at least a hundred times. That curveball xwOBA of .118 places him second in all of baseball among pitchers who had at least ten batted ball events against their curveball behind only Chris Bassitt. Yes, I’ve cherry picked some stats here and it’s only a sample of 35 innings, but that sounds worlds away from the guy with a fastball in the low 90s and average to above-average breaking stuff that was described before the season.

We see an even greater velocity improvement than we saw from Castillo, Mahle, and DeSclafani. If we had spin data from the minors, I’d bet we see some big spin improvements, too. These improvements mirror what we’ve seen from other BRPM graduates, so I’m inclined to believe the improvement is at least somewhat real despite the small sample size. I see a guy with two plus breaking pitches and a solid sinker who has even more room to improve by increasing his active spin. I’ve heard rumblings that he’s in the run to close games, but I wouldn’t be surprised to see him get a shot to start, too. I think he could be fairly effective there, although there would be concerns about how many innings he’d be allowed to throw. However, the guy who’s more likely to start the season in the rotation in my opinion is Michael Lorenzen.

Michael Lorenzon

Lorenzen has already been mentioned as a potential 5th starter by David Bell and I’d consider him the favorite to win right now because of the variety of pitches he throws and his advantage in track record over Antone. He’s been a fairly effective reliever in the Reds organization for a few years now, so why are we just now hearing rumblings about him starting? It starts with the fastball.

| MICHAEL LORENZEN FASTBALL IMPROVEMENTS 2018 TO 2020 | ||||

| FB Velocity | FB Spin | High FB % | FB SwStr% | |

| 2018 | 95.4 | 2381 | 19.6 | 7.8 |

| 2019 | 97.2 | 2538 | 28.6 | 14.9 |

| 2020 | 96.8 | 2528 | 28.9 | 15.4 |

We see that Lorenzen threw his fastball faster, with more spin, and higher in the zone on average making for an overall considerably more effective pitch. In addition to these improvements, he upped his usage of his four-seamer from 12% in 2018 to 33% in 2020 and conversely dropped his sinker usage from 40% in 2018 to just 8% in 2020. The Reds mantra of throwing the fastball higher and harder rings true yet again. What about his other pitches?

| MICHAEL LORENZEN SECONDARY PITCHES 2018 TO 2020 | ||||||

| Slider usage % | Slider Zone % | Slider SwStr% | Changeup Usage | Changeup Spin | Changeup SwStr% | |

| 2018 | 10.5 | 49.6 | 11.1 | 7.4 | 1888 | 15.6 |

| 2019 | 9.8 | 35.4 | 20.5 | 19.5 | 2150 | 26.5 |

| 2020 | 17.4 | 21.7 | 23.6 | 17.8 | 2149 | 23.1 |

Lorenzen missed a ton more bats in 2019 and 2020 than he did in 2018. His overall swinging strike rate went from 6.8% to 13.9% to 14.5% His changeup picked up a bunch more life due to the increase in spin and he simply stopped catching so much of the zone with his slider. He also increased his usage of these pitches: first the changeup in 2019, then also the slider in 2020. Lorenzen has a much improved fastball, effective out pitches against both lefties and righties, and a couple other weapons to toss in here and there. Given the Reds history over the past couple years, who knows, maybe they can turn that curveball into a weapon, too. Overall, I like what I’m seeing from Lorenzen. Like Antone, concerns about innings volume would keep him suppressed in fantasy rankings for now, but I think whoever is named the fifth starter has the stuff to come out and provide some effective innings.

Conclusions and Speculation

In the fallout of the 2014/2015 firesale and subsequent pitching collapse, the Reds decided to bring on a manager who would focus on the development of young players in David Bell. The organizational changes that Bell made revolutionized the Reds pitching training program and pitching philosophy leading to significant improvements up and down the pitching staff in the following metrics:

- Average fastball velocity

- Spin rate on breaking balls

- Swings and misses (fueled both by improvements in pitch quality and pitch placement)

- Overall K-rate

With established veterans who came to the Reds organization and a few veterans with several years of experience in the organization like Raisel Iglesias, we saw strikeout rate improvements over and above what could be explained by improvements in spin rate or fastball velocity implying that other changes and improvements were made to improve strikeout rate that aren’t captured in the analysis done above.

What could this mean for 2021 and beyond? The biggest name on the Reds staff that I haven’t mentioned is Wade Miley. Like DeSclafani, Miley had an injury-riddled 2020 which left us with little data work with and little reason to put much faith in the data we have. If the formula for established veterans holds true, we’d expect improvements in spin rate on his curveball and smarter location of his cutter to increase his K-rate. The Reds also recently acquired former top-10 overall pick Jeff Hoffman from the Rockies. It’s tough to say whether they see him more as a starter or a reliever for them (I see him more in the bullpen, personally), but maybe he’s young enough to see a velocity bump and a bump in swinging strike rate on the fastball by throwing higher in the zone. I’d also be remiss if I didn’t at least mention Lucas Sims whose curveball has the highest spin rate of any pitch in the majors. He’ll be in the mix to close games and has the potential to build on his strong 2020 if his slider regains its 2019 level of effectiveness.

Top prospects Nick Lodolo and Hunter Greene could also benefit from this system. Lodolo’s plus curveball could play up even more if the Reds training program can add 1.5 mph to his fastball like we saw from other young pitchers in the Reds organization. Greene’s fastball likely won’t see a top-end increase as he already tops out at 103; however we may see him sit towards the higher end of his range more often. What would be more important for Greene would be taking the improvements in spin we saw from guys like DeSclafani, Mahle, Gray, and Bauer to develop a more effective breaking ball. Both Lodolo and Greene might be worth bumping up in dynasty rankings given the recent success of the Reds development and training program with fringe prospects like Tejay Antone.

It may take another year or two to know for sure, but we could be looking at the emergence of a franchise on the forefront of pitcher development. As the Reds consider their future and talks swirl of another rebuild like the one we saw in 2014 and 2015 that saw the likes of Mat Latos, Johnny Cueto, and Aroldis Chapman leave Cincinnati, Reds fans can at least be comforted by an improved training and prospect development program that will prevent an organizational collapse like what we saw in 2016 and 2017.

Data Visualization by @Kollauf on Twitter

Featured Image by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)