The base tenet of baseball offense is quite simple: See ball, hit ball. All the better if one can see ball, hit ball, and do so quite hard. Arguably, no two players are better at doing so than the Atlanta Braves‘ Matt Olson and Ronald Acuña Jr..

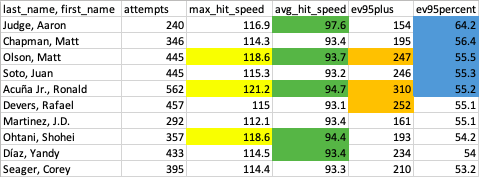

Although a rudimentary measure of the extent to which one hits the ball hard, Olson and Acuña were the only two athletes in all of MLB in 2023 to rank in the top five in max exit velocity, average exit velocity, exit velocity of 95+ mph, and percentage of balls hit 95+ mph, according to Statcast. (If you’re more of a barrels person, Acuña ranked tied for second with an 11.7 barrel rate, while Olson ranked 10th (10.1%). No matter how you look at it, these dudes rake.)

It should come as no surprise that both Olson and Acuña put together MVP-caliber seasons this past season and were the driving force behind Atlanta’s 104 wins and league-best +231 run differential. Olson led MLB with a career-high 54 home runs, while Acuña added 41 of his own (another statistic in which both finished in the top five across MLB). Interestingly, both athletes produce their power in biomechanically distinct ways, though they share certain characteristics.

Olson taps into the concept of preloading, turning his body into a tightly coiled spring waiting to unleash his stored potential energy in an intense kinetic explosion.

From a kinesiological perspective, preloading involves putting tension through a group of muscles to “store” potential energy in the contractile (i.e. muscles) and non-contractile (i.e. tendons and connective tissue), which, in turn, allows for the body to release more force during the swing, lift, etc. There are a couple of body segments to pay attention to in the clip above to grasp the idea of preloading. First, tune into Olson’s back shoulder and hands and how they move relative to the rest of his body; they’re moving towards the Coca-Cola sign while the rest is headed towards Visit Lake Oconee. This places tension through the core, winding it like a towel waiting to be snapped. Simultaneously, he crouches onto his back leg and dips his front shoulder, further building up potential energy throughout his hips and core. This energy is released at ball contact when Olson meets the middle-middle fastball (not an ideal location!) with full extension of his hands and front knee, which is associated with fast swing speeds and offensive performance. Olson’s back foot flies off the ground momentarily, a visual representation of force propulsively transferred from the hips and core through the bat.

If Olson’s swing is equivalent to that of a corkscrewing spring, Acuña’s is a firecracker. There’s no wasted movement, just pure fast-twitch kinetic energy.

While Acuña’s swing still possesses some preloading (every swing of a baseball bat does to some extent), it’s much less of a driving force than Olson’s. Instead, Acuña derives most of his power from the strength of his legs combined with the gracefully violent torque of his hips. Acuña’s hips go from static to rotated fully open in fewer than 10 frames; that is incredible speed. Meanwhile, his back leg absorbs all of his body weight and thrusts it forward in lockstep with his hands. (Seriously, go frame-by-frame if you have to. Acuña’s hands, torso, and hips move as a unit. It is a textbook swing.) He also maintains the ability to “stay tall” (i.e. not bending at the waist) regardless of pitch location; from a technical standpoint, doing so reduces his moment of inertia—much like a figure skater pulling in their arms while spinning—causing increased swing velocity, and, thus, exit velocity and wOBA.

The result is an efficient transfer of power from the back foot, through the hips, to the hands, with each body segment magnifying the force Acuña is about to unleash on poor Emmet Sheehan’s fastball. Similar to Olson, Acuña meets the ball with full extension of his hands and lead knee and his back foot leaves the earth as force is transferred from the back leg to the rest of his body.

The swing biomechanics of Olson and Acuña show that there is more than one way to drive the ball over the fence. At the end of the day, torque generation and amplification and the efficient transfer of energy from the back foot to the hands are what drive home run power, but Atlanta’s sluggers prove that this can be accomplished in unique ways depending on the athlete’s preferences and characteristics. Launch angle, swing plane, and resting position are all important for success at the MLB level but to mash like Olson and Acuña, batters need to be able to produce force at an explosive rate.

Fun article!