Pitching is both an art form and a science. Watching a pitcher throwing perfect strikes from 60 feet and six inches away is like enjoying an artist painting a piece. But now we also have the tools to understand the science behind what makes pitchers great. Statcast data allows us to collectively ooh and ahh at Jacob DeGrom making hitters look stupid while also visualizing the vertical break of his slider that fuels his dominance. The same data also allows us to watch mediocre pitchers toss six shutout innings while getting barreled up every at-bat and visualize Jesse Pinkman in our heads.

https://gfycat.com/defenselesswideeyedbrahmanbull

Analytics are meant to connect the dots behind a player’s performance. But every so often, you run into things that defy explanation. Over the past couple of seasons, a single anomaly keeps cropping up in my fantasy deep dives. This pitcher’s profile is so difficult to harmonize with his results and yet, he keeps getting away with it. I present to you Cal Quantrill of the Cleveland Guardians. The eye test and peripheral stats suggest a pitcher with little intrigue, yet he’s quietly been one of the better arms in baseball for a couple seasons now. Let’s go on an investigation to solve the Cal Quantrill Quandary.

The Case Subject

Cal Quantrill was the eighth overall pick by the San Diego Padres in the 2016 MLB Draft, where he was considered a top arm among that year’s crop. His minor league numbers across three levels were nothing to write home about. Quantrill earned his call-up in 2019 and posted a suboptimal 5.16 ERA across 18 starts. The 2020 season was an improvement, as he posted a 2.60 ERA pitching out of the pen, but it resulted in him being traded mid-season to Cleveland. As luck would have it, this trade set the stage for his emergence.

Midway through the 2021 season, the injury-decimated Guardians decided to make Quantrill a full-time starter again. After his July 4th start against the Astros, he had a 4.20 ERA and 4.07 FIP. Essentially, he was pitching to his expected statistics. But then something clicked. He went on to record 12 quality starts over his last 15 outings. After the season concluded, Quantrill had a 2.89 ERA…and a 4.07 FIP. Based on that stat alone, one might be quick to write this off as a mere hot streak. But look at what he’s done over a larger sample size.

Of all the starting pitchers with at least 300 innings pitched since the start of 2021, here is where Quantrill lands on the ERA leaderboard.

There he is, rounding out the top 15, and keeping company with some great names. But how legitimate is this? Let’s take FIP, a purer measure of skill, and subtract by ERA to see who had the biggest difference between their expected and actual statistics.

Outperforming your FIP is not all that uncommon, but to do it by almost one whole run is quite the stroke of luck. Quantrill’s other peripherals are equally unimpressive (his SIERA is 4.50 over this span). Across a smaller sample size, you could conclude that he can’t keep getting away with it. But now 330 innings later, there must be something more to this. Let’s explore three hypotheses for how he has been successful.

The Orthodox Hypothesis

The elite pitchers in the league have common threads. They don’t walk many hitters, they rack up the strikeouts, and they keep the ball in the yard. There are of course exceptions, but generally, the best pitchers are excellent in at least two of the three. My first thought is whether Cal Quantrill fits this mold. Let’s look at his strikeout, walk, and home run per 9 innings rates over the last two seasons.

It doesn’t take long to see holes in this hypothesis. Quantrill’s strikeout rate is abysmal – he ranked 49th out of 50 qualified starting pitchers last season. His walk and home run rates are decent, but not spectacular. Now, this isn’t necessarily a death knell for pitchers though. Greg Maddux had a career K/9 rate of about 6 and he made it to Cooperstown. Of course, Maddux also happened to be the greatest pitcher ever at inducing weak contact. Is Quantrill following a similar blueprint? We need to check out the batted ball data.

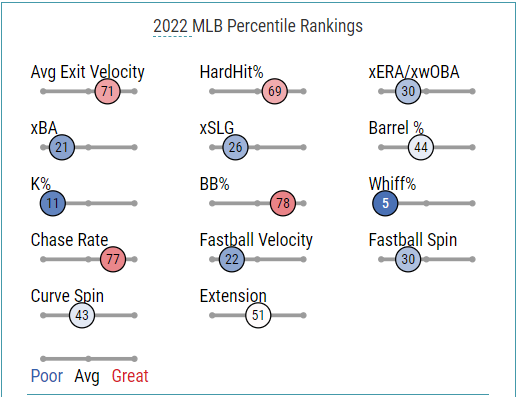

Like the pitcher himself, Quantrill’s Savant page is riddled with contradictions. He does induce a fair amount of weak contact but is also not averse to getting barreled up. He owns a strong chase rate out of the zone and yet is among the worst at getting swings and misses overall. Given that he pitches to contact, surely he’s a groundball pitcher, right? Nope, his groundball rate is 43% – slightly below the league average. Quantrill just doesn’t miss enough bats and the quality of contact he gives up cannot mitigate this fact. These are not the keys to success we are looking for.

The Pitch-Mix Hypothesis

In many cases, post-hype breakouts can be attributed to a simple tweak in the pitch mix. Early in his career, Jake Arrieta scuffled for years as an Orioles prospect armed with a hard, but ineffective four-seamer and a big curve. When he got to the Cubs, they had him lean into a deadly sinker/slider combo. The result was Arrieta winning a Cy Young at the age of 29. Maybe a pitch mix tweak is what unlocked Quantrill too. After all, the Cleveland pitching factory is famous for cranking out good young arms. Guardians pitching coach Carl Willis has overseen five(!) Cy Young winners under his tutelage. So let’s dive further.

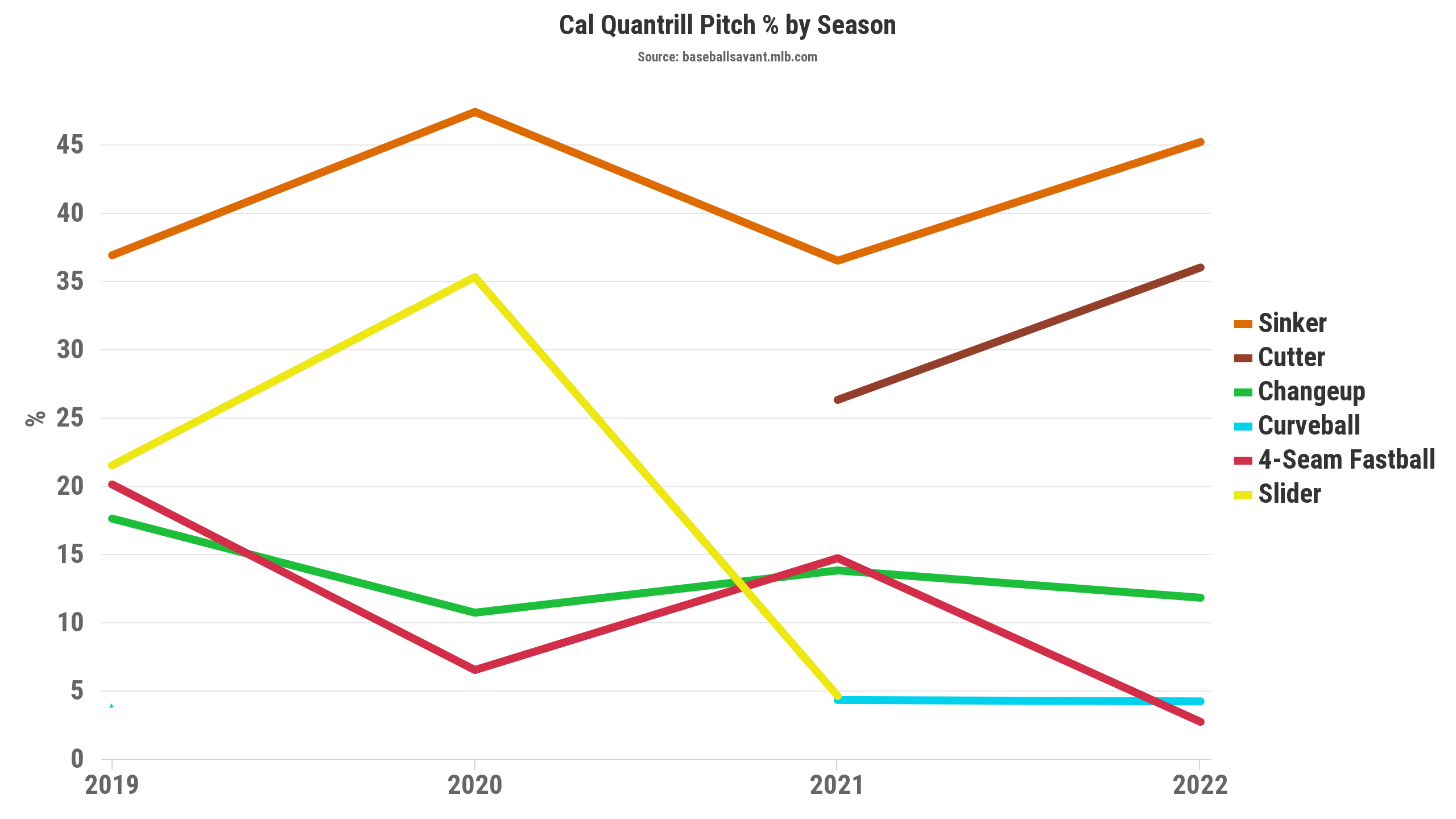

Here is Quantrill’s pitch repertoire by season. After coming over to Cleveland, he ditched his slider for a curve and introduced a cutter while phasing out his 4-seamer almost entirely. It would be easy to jump to conclusions and dub his newfound cutter as some magic cure-all, but let’s look at the pitches in question first. Daniel Port wrote a fantastic breakdown on Quantrill’s arsenal and approach back in August 2021, during his second-half hot streak. Has he been able to carry over his success since then?

If you’re a hitter coming up to bat against Cal Quantrill, chances are you’ll see either the sinker or the cutter. In 2022, he threw those two pitches combined nearly 80% of the time. That’s Lance Lynn-esque fastball reliance. So you would think there must be something special about this pitch mix.

Cal Quantrill, 94mph Paint. 🎨🖌️ pic.twitter.com/tpGpRi66bq

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) August 30, 2022

Cal Quantrill, Dirty 90mph Cutter…and Sword. ⚔️ pic.twitter.com/jI7ZSK718F

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) October 12, 2022

Except the problem here is once you look closer, neither pitch passes the smell test. The sinker comes in around 92-94 MPH with below-average break. What Quantrill does well is locating the pitch to both sides of the plate, but the fact remains that the pitch itself is pretty vanilla. His cutter, on the other hand, was an absolute revelation in 2021, ranking as one of the better pitches in baseball. Unfortunately, it regressed drastically in 2022 as he upped its usage. Like golf, the lower the better when it comes to run value.

Quantrill also possesses a decent changeup and a curveball that he saves for a rainy day, but neither pitch gets enough usage to truly tip the scales. So what we have learned is that Cal Quantrill is a fly-ball pitcher with average stuff who throws over 80% fastballs. The pitch-mix hypothesis might explain why he has improved these last couple of seasons, but it still doesn’t quite add up to the pitcher he has been.

The Intangibles Hypothesis

So far, we have struggled to explain Quantrill’s performance based on his abilities. But how about the abilities of those around him? After all, the calculation for FIP focuses only on batted-ball events that a pitcher can control and not independent factors like defense and park conditions. Could Quantrill be a beneficiary of his team context and home park?

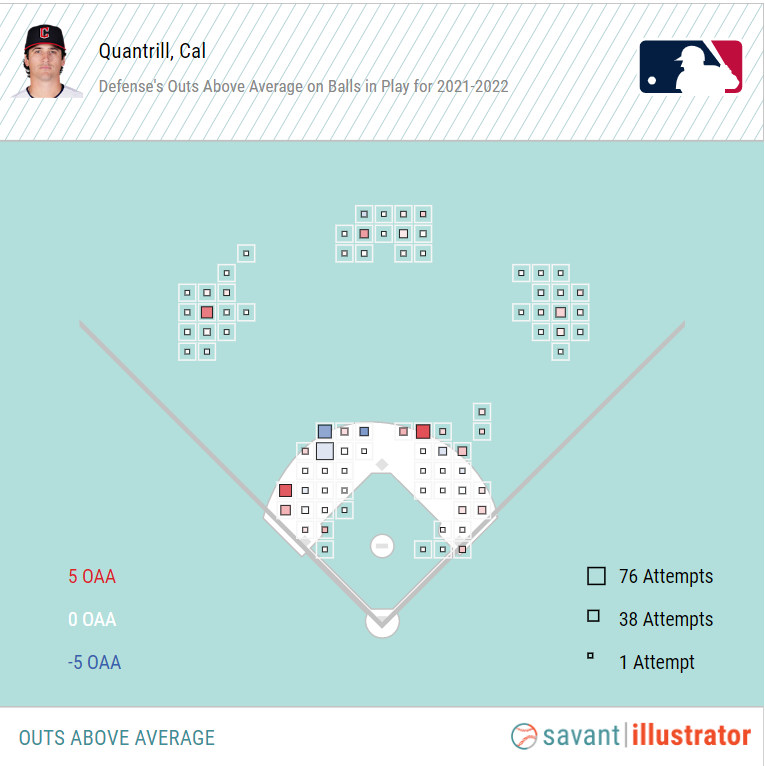

First, let’s look at the team defense behind him. The best defensive statistic for the purposes of this exercise is Outs Above Average, which is the cumulative effect of all the individual plays a fielder has made.

The red squares show where the Cleveland defense has been a strong asset and the blue squares are the liability areas. Looking at the Guardians roster, Gold Glove outfielders Myles Straw and Steven Kwan grade out as elite defenders at their position. Being the fly-ball pitcher that Quantrill is, Straw and Kwan’s excellence would allow him to overperform his expected batted-ball outcomes. The infield defense has all-star José Ramírez at the hot corner and another Gold Glover Andrés Giménez at second. In terms of overall team Defensive Runs Saved (DRS) in 2022, the Guardians came in third in the league.

Another understated asset to the Cleveland squad is backstop Austin Hedges. Though just a career .189 hitter, Hedges is a defensive wizard behind the plate who leads all qualified catchers in defensive runs saved (75) since 2015. While no good metrics exist for quantifying pitch calling, Hedges notably made the news for his mastery of PitchCom, even reprogramming the tech to include his own voice. Cleveland clearly saw the value of putting him in the lineup every day despite his offensive shortcomings, so it’s clear the veteran catcher greatly impacted the rotation.

The other reason I wanted to explore this hypothesis is due to this incredible Quantrillian stat. In his Guardians career, Quantrill is 14-0 with a 2.88 ERA in his career pitching at home during the regular season. He has made 34 starts and has never lost a decision. Now Progressive Field is not really a pitcher’s haven. Based on Statcast, over the last three years, it has graded out as 16th among all ballparks in the league with a park factor of 99. In comparison, the most hitter-friendly ballpark is Coors Field with a park factor of 112 and the most pitcher-friendly ballpark is T-Mobile Park with a park factor of 91. However, there are clues that Quantrill’s profile is actually a perfect fit for the confines of his home stadium.

The unique feature of Progressive Field is its mini-Green Monster wall in left field that stands 19 feet tall. In contrast, right field has just a 9-foot wall and doesn’t keep many fly balls in with its average dimensions. Notice how Quantrill attacks hitters according to his ballpark’s strengths. Forcing lefties to hit fly balls to the opposite field almost one-third of the time is a wise tactic since that left field wall suppresses home runs. Check out this booming double hit off the bat of Steven Duggar that gets held in by the mini-Monster.

https://gfycat.com/thirdtestyachillestang

On a 2-0 count, Quantrill leaves a sinker up and middle-away. Duggar squares it up well, but by taking on the big wall in left, he has to settle for a double. Not all of this is purely luck, as Quantrill deserves credit for attacking lefties this way. Here is a great example where he forces Shohei Ohtani to beat him opposite field and executes a much better pitch.

https://gfycat.com/viciousserenelaughingthrush

Righties who try to attack the more forgiving right field are thwarted, as the sinkerballer induces them into pulling the ball on the ground at a much higher rate. Batted ball data is always subject to variance, but this contrast displays how Progressive Field enables Quantrill to pitch according to his game plan with excellent results. This seems to be the most promising hypothesis thus far. A combination of good defense and utilizing the confines of his home ballpark definitely contribute to Quantrill’s numbers, especially once you check his road splits.

Conclusion

Sherlock Holmes once said, “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.” Well, we have a lot of the data, but figuring out the mystery of Cal Quantrill has proven far from elementary. That’s the beauty of this game of baseball. Sometimes things don’t make sense, but we can still appreciate the thing itself. There may be varying takeaways from the Cal Quantrill quandary. Analytics skeptics may view him as the poster boy for why expected stats don’t matter. Data devotees may view him as a luck merchant who will soon get slammed with negative regression. Personally, I think the peripheral stats do speak more accurately to Quantrill’s true ability. But we should recognize that he is a solid pitcher who has mastered the art of succeeding in his environment with the tools he has. Pitching is truly an art form and ingenuity often beats talent. Don’t rush to get him on your fantasy teams unless it’s a quality start league, but if you ever catch a game with Cal on the mound, enjoy watching him paint.

Featured image by Justin Paradis (@JustParaDesigns on Twitter)

As a skeptic of expected stats, I see another possible conclusion: Expected stats are as unreliable as data devotees believe traditional stats to be. The difference between Quantrill’s 2021 FIP (4.07) and ERA (2.89) is 1.18, about 29%. The difference between his 2022 FIP (4.12) and ERA (3.38) is .74, about 18%. Pretty large margins of error. Yeah, small sample size and ERA doesn’t filter out factors beyond the pitcher’s control (except baseball isn’t played in a vacuum). Sure, all things being relative, I suppose expected stats are useful for some purpose, but is the normal, typical, average fan able to look at a box score (and season totals) and figure out FIP or any other expected stat?

Appreciate the comments, Bob! I fully agree with you that expected stats have their flaws. Try as we might, us humans haven’t quite figured out the “seeing into the future” part yet, so we’re stuck with these predictive tools. I like to think of advanced stats and traditional stats working together to measure player performance, which is usually the rule rather than the exception. For every Quantrill story, there’s also a story like Alex Cobb’s. Last season, when the calendar flipped to June 2022, he owned a gross 6 ERA, but the expected stats showed he was extremely unlucky (his FIP was under 3). Sure enough, he finished out the second half being one of the better pitchers in baseball. The utility of expected stats shows up in situations like these. But I do agree the value of this is far greater for, say the Giants organization, than it is for fans like you and me.

Thanks for the reply, Tim. This is the first season I’ve done more than just shrug off FIP and other expected stats, but the more I look into them (FIP in particular) the less I understand it. Yes, there are examples of pitchers’ ERA exceeding the calculated FIP. ?Curious that you used Alex Cobb to illustrate the flip side of the Quantrill quandary. Cobb was a streamer in our 10-team, H2H points league last season – and we all mis-timed streaming him: he’d have a decent game, be streamed, and have a poor outing, and be dropped. That cycle seemed to repeat itself throughout the season (after I dropped him in June). I don’t think any of us were happy with Cobb’s season. To me, using “lucky” and “unlucky” to explain the differences between ERA and FIP is a rationalization of/for FIP. So, until it makes more sense to me, I’ll not use FIP (and other expected stats) to analyze players for fantasy baseball. I agree, expected stats are more useful to MLB organizations than to me (and the other managers in our fantasy league.

I’m with you there. As both his fantasy owner and a Giants fan, Cobb was by far the most frustrating pitcher to deal with last season. He still has great stuff and hopefully the defense helps him out a little more this year. I appreciate you giving expected stats a fair shake and respect your reasoning. Best of luck in your league this year.

Thanks for the exchange, Tim. I haven’t given up on Cobb: he could be a late-round surprise.

Really interesting analysis, but I’m confused about why you keep calling Quantrill a “fly-ball pitcher.” His player page shows that his four-year career average is 34% (never lower than 33% or higher than 35%), which is identical to last year’s major-league average for all SP. Maybe I’m misunderstanding something but it seems like a fly-ball pitcher would allow more fly balls than usual. (Quantrill actually is pretty much average across the board, with a career GB% of 45 compared to 44 for all SP, and a line drive rate of 21% vs. the typical 22.)

Very fair point. I took the definition of a groundball pitcher being above 50% GB rate and anyone who doesn’t hit that threshold is a fly-ball pitcher. Looking back, I realize that might not be good practice especially in today’s hitting environment. Wish there was a defined third category to describe pitchers who don’t necessarily qualify as either. Good call there, thanks for the comment.