Every season, a handful of Major League Baseball players swap teams either by trade or through the waiver wire. Relief pitchers, in particular, are among the most fungible players on a team’s roster. They get passed around more frequently than any other position and find themselves being afforded fresh starts in new cities quite often.

This is largely due to the relative season-to-season volatility of reliever performance. It’s not uncommon for a bullpen arm to put up sparkling numbers in one season, only to be average or worse the following campaign. Even Josh Hader, arguably the most dominant closer of this generation, put up a 5.22 ERA in 2022 sandwiched between a 1.23 in 2021 and 1.28 in 2023. It’s nearly impossible to reliably predict how well relievers are going to perform on the surface in a given season.

Even more difficult is projecting how they’ll respond to joining a new organization in the middle of the season. Often, the range of outcomes in this scenario goes from a marginal dip in performance thanks to expected regression to a notable improvement as a result of exposure to new ideas and coaching philosophies.

We saw plenty of relievers fall in this expected range of outcomes throughout the 2023 season, but what if I told you there was one reliever who swapped teams in the middle of the season and instantly went from a fringe-average contributor to one of the most unhittable bullpen weapons in recent memory?

The Emergence

Such is the story of Robert Stephenson, who was flipped from the Pirates to the Rays on June 2 of this past season. It was a low-profile trade at the time, mostly due to Stephenson’s pedestrian performance in Pittsburgh. Before the trade, he posted a 5.14 ERA, 27.9 K%, and 13.1 BB% over 14 innings. The move was seen as nothing more than a depth play for the perpetually injury-plagued Rays pitching staff.

The Rays didn’t quite see it that way.

I want to really hone in on how ridiculous that improvement in his strikeout and walk rates is. He went from punching hitters out at a slightly above-league-average rate and struggling to keep walks in check to posting the second-best K-BB% in the entire sport from June onwards (min. 20 IP).

His ability to draw whiffs last season wasn’t just the best in the league by a considerable margin, it was among the most dominant displays of swing-and-miss stuff we’ve ever seen. Hitters swung and missed at 24.8% of the pitches Stephenson threw in 2023. Almost a quarter of his total pitches. That has only been bested once in recorded baseball history by Brad Lidge back in 2004, who posted a 25.1% swinging-strike rate.

That’s not even the ridiculous part. If you take out Stephenson’s early-season struggles in Pittsburgh, his swinging-strike rate for the remainder of the season was over 30%. So, all things considered, it’s not outlandish to say the Rays’ version of Robert Stephenson just showed us the best run of pure bat-missing ability we’ve seen in baseball history.

This naturally prompts the question: how? Surely something had to change dramatically after the trade to result in a historic stretch of dominance like this.

Was there a change? Yes, absolutely. Was it dramatic? Actually, not as dramatic as you might expect.

The Evolution

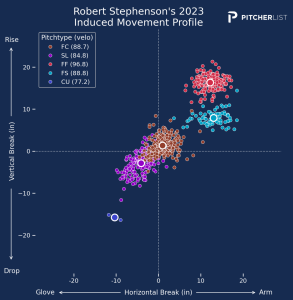

With a spike in performance like the one Stephenson experienced in 2023, you’d expect to see an entirely different player before and after the trade to Tampa Bay. The majority of his arsenal, however, remained mostly the same.

He didn’t shift around the mix on his existing pitches much at all, using his four-seamer and split-change the exact same amount in Tampa Bay as he did in Pittsburgh (40.9% and 3.7%, respectively). Stephenson has always been a slider-first guy. It’s been his best offering throughout the entirety of his career, dating back to his days as a starter. That didn’t change in Tampa Bay either, as he threw the slider almost 50% of the time.

So, Stephenson’s pitch mix didn’t budge much at all. Instead, the clearest and most impactful change he made upon his arrival in Tampa Bay was the shape of that slider.

It’s never been a big, sweepy breaking ball like the ones you see thrown frequently these days, instead taking much more of a tight gyro-slider shape. A common approach with pitchers of this ilk is to see if they are capable of throwing the sweeper to give them two distinct slider shapes, but that is not the approach Stephenson and the Rays took.

Instead, they opted to lean even harder into that bullet slider profile.

The terminology gets a bit muddy in this zone, but by most conventional accounts, the new version of Stephenson’s slider he developed with the Rays is more of a cutter than a true slider. That drop in horizontal movement and increase in ride and velo bring it closer to a fastball than its previous iteration.

Whatever you want to call it, this pitch instantly became one of the most unhittable offerings thrown by any pitcher in the league. From Stephenson’s first game with the Rays on June 3rd to the end of the season, his cutter registered an unholy 61.7% whiff rate, 36.1% swinging-strike rate, and .183 wOBA against.

That 36.1% swinging-strike rate is the single best mark on an individual pitch thrown at least 100 times by any pitcher since the pitch-tracking era began, beating out Jacob deGrom’s slider by over 3%. It was that good.

You don’t even have to dig too deep into the numbers to ascertain the quality of this change. It was clear just by watching Stephenson deploy this new cutter that he was borderline untouchable.

The Rays seem to do this every year with at least one bullpen arm, but this may have been their magnum opus of pitcher reclamation projects. By making one notable shape adjustment to Stephenson’s best pitch and instilling confidence in him to pound the zone with it, they effectively manufactured a bullpen ace who could reliably dominate even the best right-handed hitters in the game.

Seriously, righties hit a whopping .115/.144/.230 with a .162 wOBA against him after the trade. He faced 90 right-handed hitters as a Ray and struck out 44 of them while surrendering only 6 extra-base hits.

The Lessons

What you still might be wondering about Stephenson’s emergence is exactly how this change in primary breaking ball shape led to such a drastic improvement in performance. While I can’t be 100% sure on that front, I do have a theory as to why hitters were having such a hard time with the pitch.

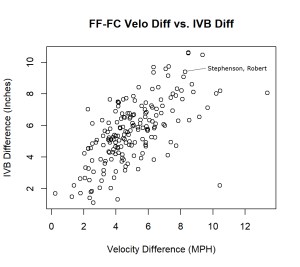

Out of curiosity, I built a quick regression model relating differences in movement profiles of Stephenson’s two primary offerings: the four-seam fastball and the cutter. The goal here was to get an idea of how the ideal four-seamer and cutter play off of each other in terms of velocity and movement. What I found was interesting.

With the new cutter he developed in Tampa Bay, Stephenson ranked in the 93rd percentile in velocity difference between the fastball and cutter, and the 97th percentile in vertical movement difference between them.

By tightening up the shape of his slider and placing it more in the in-between zone between slider and cutter, Stephenson effectively created an interaction between fastball and cutter that is almost entirely unique to him. Hitters were left having to respect his 96 MPH four-seamer with 16+ inches of ride and almost 13 inches of arm-side run, but needing to defend against a devastating cutter that resides almost exactly on the 0/0 movement line.

Essentially, Stephenson was able to craft an arsenal that can leverage both planes while featuring unique interactions between movement profiles, all with two primary pitches.

There’s also that little note I made before about his command improving. That walk rate being slashed from 13.1% in Pittsburgh to 5.7% in Tampa Bay was no mere blip on the radar. His Location+ on the slider/cutter improved from 100 to 103, which is a more significant jump than you might expect given that it’s Stephenson’s primary offering.

It is also general consensus that tigher sliders are easier to command given their closer proximity to fastballs in terms of movement profile. Trying to get Stephenson to throw a sweeper likely would have worsened his command issue and left him without a reliable primary offering, something he couldn’t afford.

In summation, Stephenson’s evolution was likely the result of creating a unique interaction between the movement profiles of his two primary offerings that he could actually command in and around the zone. It has always been the Rays M.O. to have their pitchers throw their best pitch often and in the zone, but in Stephenson’s case, changing the slider to a tighter cutter seems to have had a trickle-down effect that resulted in a full realization of the potential that made him a first-round pick back in 2011.

Now, what can this case study teach us about breaking balls in general? Why aren’t more pitchers trying to ditch the slider for a bullet variation or a true cutter if it yielded such great results for Stephenson?

I think the answer lies in the fact that pitching development is, ideally, a highly individualized process. You’ll occasionally hear about certain organizations encouraging most, if not all of their minor league arms to throw a certain pitch or deploy a certain approach. The Yankees were notable for having their MiLB pitchers trying to develop sweepers back when the craze around that pitch was in its infancy.

Organization-wide pitch trends don’t sound so bad on the surface, but also worth considering is how hitters counter-adjust to general league pitch trends over time. Pertinent to Stephenson’s case is how hitters have significantly improved against sliders and sweepers over just the last handful of seasons, as can be seen in this piece written last July by Will Sammons and Eno Sarris.

Realistically, I don’t think you can reliably apply any overly general “framework” to pitching development and expect to yield great results. I’ve always thought that every single pitcher who steps on a Major League mound has something unique about them that, if utilized properly, can lead to success at the highest level. The best pitching development organizations in the sport today do a great job of identifying what that marketable skill is and executing a plan to bring it forward.

Perhaps, then, the rhetoric around pitching development as a whole should start shifting away from simply “throwing your best pitch more often,” and towards “leaning into what makes you entirely unique among your contemporaries.” Striving to mold your breaking ball shape around the common perception of the “ideal slider/sweeper/curveball,” while useful as a starting point for pitch design, leaves you at risk of becoming somewhat generic in the long run.

Take our man Robert Stephenson as a prime example. He certainly could have tried to join the sweeper craze to revitalize his career. He also could have taken the advice of stuff models and tried to throw his new cutter as hard as possible with more horizontal movement.

Instead, he opted not to totally abandon his gift for spinning the ball and found an in-between that catered to his tendencies, pitching approach, and the remainder of his arsenal. The result was what can only be described as one of the most dominant stretches of pitching in modern baseball history.

The fact that hitters made contact against Stephenson’s cutter just over half as much as the average pitch of that type should tell you all you need to know. Not everyone is going to be able to attain this level of dominance by making such relatively small changes to their arsenal, but I think baseball would be a whole lot more enjoyable if more pitchers started doing things that only they are capable of doing on the mound.

Lowest FC Contact% & League Average (2021-Present, min. 200 P)