Jesús Luzardo oozes talent. Blessed with high-octane fastballs, a wipeout curveball, and a tumbling changeup, the 24-year-old forced Oakland’s hand into calling him up to fill out the backend of the bullpen towards the end of the 2019 season. And in that season, it only took 15 innings for Luzardo to stamp his mark on the league and be dreamt of as a powerful force for years to come, particularly when he shut out the Tampa Bay Rays for three innings while punching out four in the American League Wild Card game.

However, when he shifted back to his starting role the following season, Luzardo was underwhelming, pitching to a 4.12 ERA (4.19 FIP/ 3.88 xFIP). But that didn’t stop A’s manager Bob Melvin from starting the lefty against the White Sox and the Astros in the playoffs to poor results, yielding a combined seven earned runs in 7.2 innings.

This season offered Luzardo an opportunity to pitch to his potential and lead an Athletics rotation that raised many questions entering the year. The start of the season was rough as he was saddled with a 5.79 ERA, but then Luzardo broke his hand while playing video games. He went back to the ‘pen upon his return as James Kaprielian found success in his absence — but Luzardo struggled in relief as well. With 38 disastrous innings under his belt, ones filled with more walks (+2.3% BB in 2021), more home runs (1.37 HR/9 in 2020 to 2.61 HR/9), which totaled an ugly 6.87 ERA, the A’s had no choice but to demote the left-hander to Triple-A. Finding out what went wrong with Luzardo requires investigating why his walks and home runs have increased.

The number of free passes Luzardo has given up this season is higher than in his prior two seasons, despite throwing in the zone more often (46.6% to 49.8%) and getting a similar number of first-pitch strikes (62.5% to 60.1%) compared to a year ago. Additionally, Luzardo is also recorded roughly the same number of pitches in three-ball counts and two-strike counts this year compared to his prior two seasons. Without an obvious answer here, looking at his home runs could give us better insight into his control issues.

To investigate the home run problem, it would be best to see how Luzardo is giving up longballs — particularly by pitch.

The four-seamer is undoubtedly the biggest issue here, as the seven home runs given up on the pitch is one of the highest marks in the league, surrounded by the likes of Jorge López and Dean Kremer — in other words, not good! But if we take a closer look, it’s rather bizarre how Luzardo reached that figure.

Yuli Gurriel, 4/2/’21

https://gfycat.com/opensmoothcockerspaniel

Austin Hays, 4/25/’21, HR #2

https://gfycat.com/bonybiodegradablehapuka

Andrew Benintendi, 6/10/’21

https://gfycat.com/altruisticunderstatedbluebreastedkookaburra

If you pay close attention, you’ll notice the counts of those homers — 2-2, 0-1, 0-0. Furthermore, of those seven home runs off the four-seamer, only one of them has been in a count where the hitter has been ahead — a 3-1 blast to Shohei Ohtani. The trend follows for all of his home runs too, as the southpaw has given up three home runs this season on the first pitch of an at-bat while three more have been relinquished in two-strike counts. This speaks to a larger issue that Luzardo has had this season, and that’s pitching when in the aforementioned counts.

Note: League Average for each statistic is within the parentheses.

Now let’s look at how he’s used his pitches in those counts.

The first pitch of at-bats has incredibly difficult for pitchers to navigate during the Statcast era, and it’s no different during 2021 where batters have a .390 wOBA (.405 xwOBA). Luzardo has been considerably worse this season than the league average with a .439 wOBA, but that’s backed by a .354 xwOBA, showing he’s been a little unlucky. Nevertheless, the three dingers on the first pitch are troublesome and the best starters in the game — like Max Scherzer and Jacob deGrom — have pitched significantly better to lead off plate appearances so let’s find areas of improvement, starting with his most used pitch: the four-seamer. As you can see, Luzardo’s heater has been crushed while his other three offerings have performed quite well, particularly his offspeed pitches. If the four-seamer’s usage was decreased in favor of his other pitches — again, mostly redirected towards his non-fastball pitches — then there’s room for optimism that batters can be better kept off-balance.

When he’s ahead in the count and with two-strikes, Luzardo relies on his curveball often when he’s ahead, and rightfully so. This season, the breaker is a Money Pitch — 41.1% O-Swing, 47.5% Zone, and a whopping 30.2% SwStr. The usage of the rest of his arsenal is perplexing though. Luzardo’s four-seamer has been crushed this season (.475 wOBA/ .452 xwOBA), and while his sinker has performed decently well, he’s still throwing close to 50% fastballs in 2-strike counts — roughly the league average, but Luzardo’s fastballs have been relatively poor. Given how special his curveball is, the fact that the usage isn’t much higher seems like a misstep.

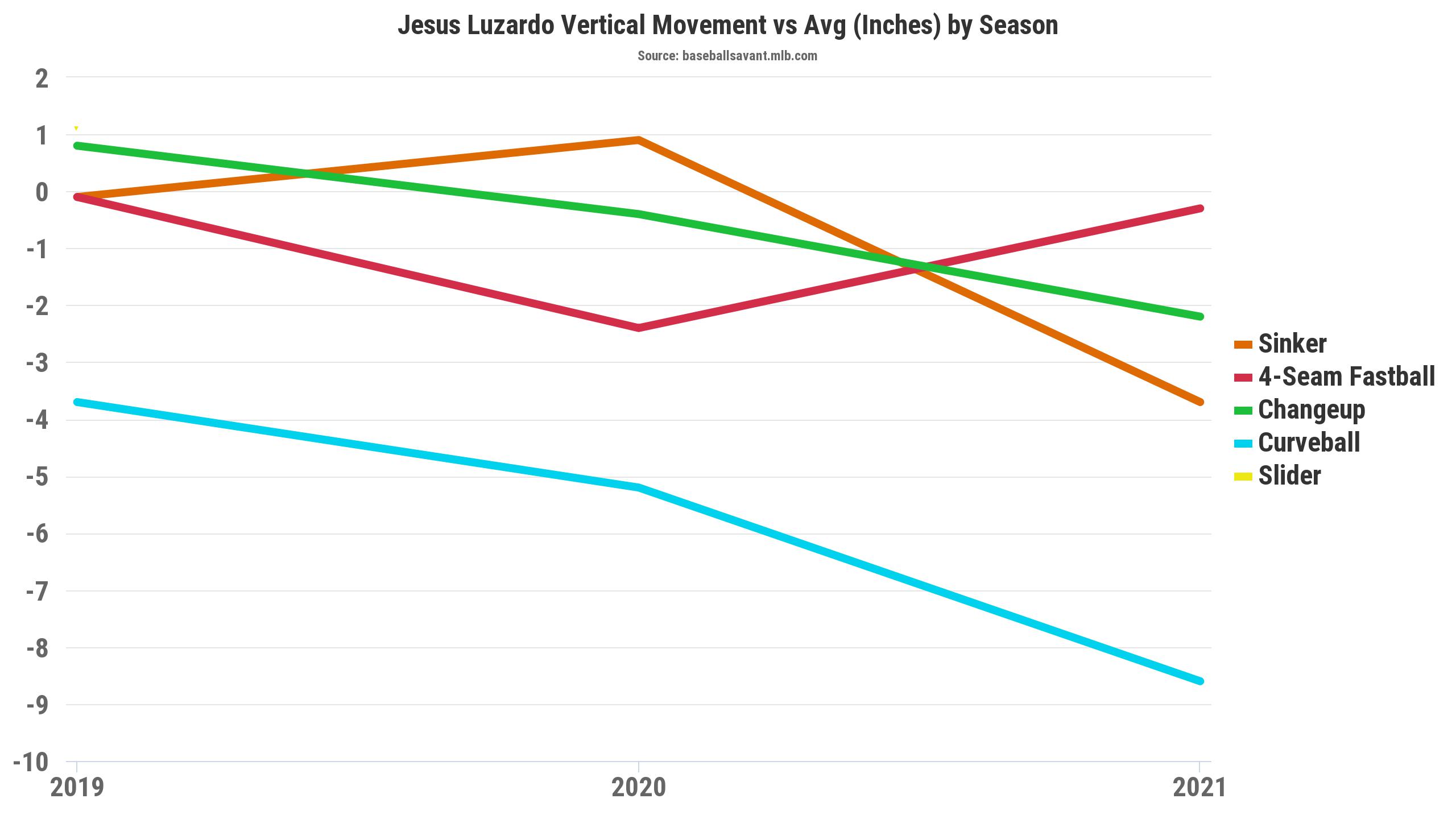

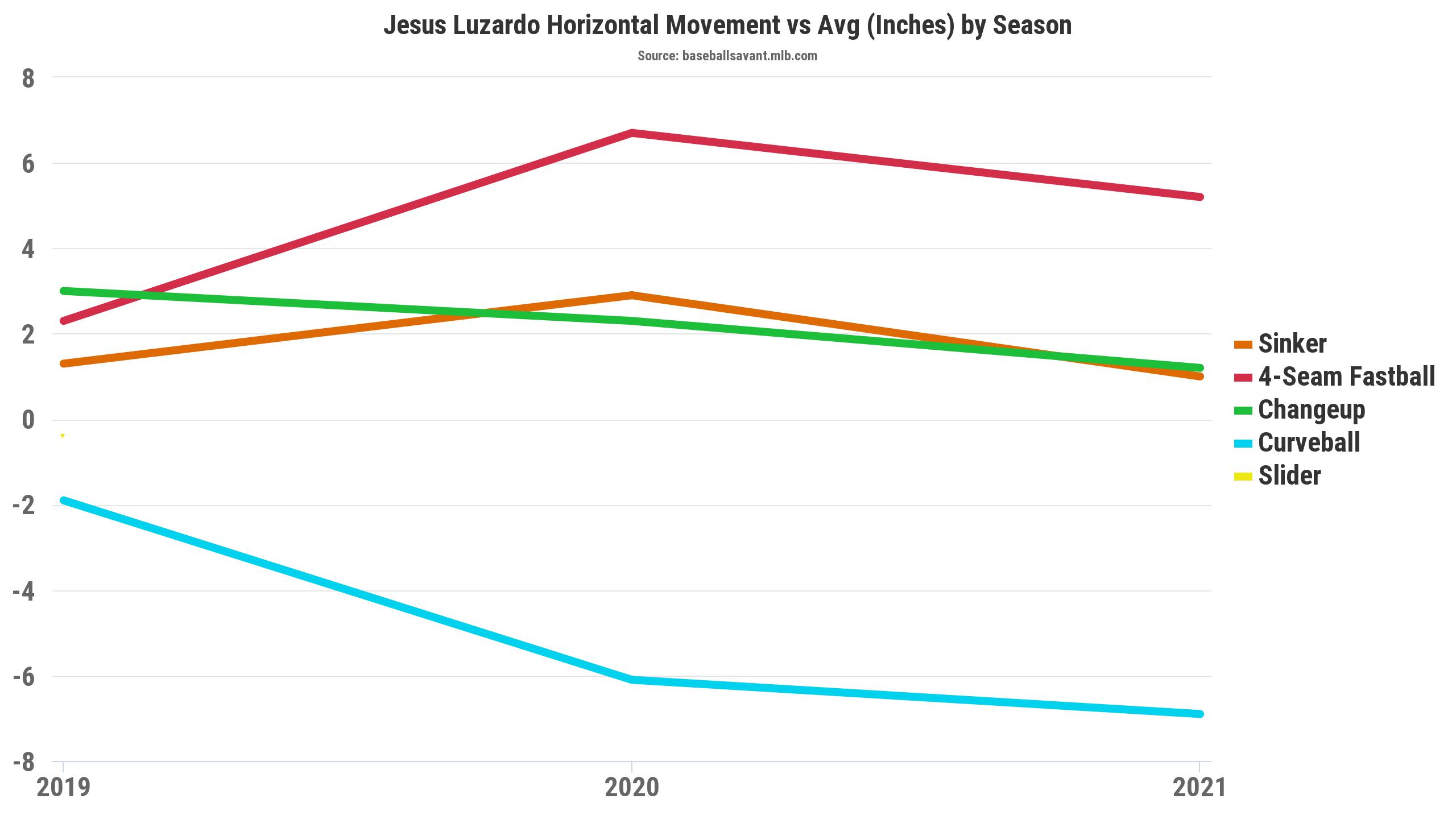

What’s also surprising is Luzardo’s low changeup usage in those counts. The pitch has been dynamite in its own right as it recorded a 21.5% SwStr from 2019-20. But this season? That figure has dwindled to 13.3%. The biggest reason for its lack of potency now is the changes in movement profile, as the changeup has lost over 2” of vertical movement (with gravity) while having 1.5” less arm-side run. However, Luzardo’s drastic shifts in pitch movement aren’t subject just to his changeup but rather all of his pitches.

Luzardo has always exhibited exceptional ‘tail’ to his pitches, but this season has shifted closer to the average movement profile on his four-seamer, sinker, and changeup. We see that those three aforementioned pitches have all “risen” and their side effects are noticeable for his vertical movement. This means despite using his changeup in the heart only 20% of the time, keeping it mostly in the shadow and chase regions, Luzardo is still only getting swings and misses a little over 13% of the time. Additionally, his sinker is also being used predominantly in the shadow region yet is still being hit hard (.413 wOBA/ .338 xwOBA). Finally, with his four-seamer, Luzardo is still tentative about using the pitch in the top shadow region of the zone, placing it in the region only 15% of the time despite good results.

While changing the usage of his pitches could benefit Luzardo, the degree of success is rather unknown. His four-seamer and sinker have generally underperformed through his career, and changing the location of those pitches might not alter the ability of the pitches enough to make them better. Considering that the sinker and changeup are both have been hit hard despite being placed away from the heart of the zone, it seems like the pitches themselves don’t fit together and that’s something that is reflected in Stuff+, where Luzardo only has a 100 Stuff+ rating. Finding ways to increase that figure is an intriguing exercise.

One idea would be to focus his arsenal on his curveball.

https://gfycat.com/forkedbeneficialgeese

The pitch itself has hardly any vertical or horizontal movement relative to the average yet possesses a lethal 30.2% swinging strike rate as we saw earlier. That comes from predominantly gyro spin on the pitch as it only exhibits 11% active spin. With that gyro spin, the breaker is the most unique in the sport as its differential between the observed and inferential spin axis is 63.2° — large seam-shifted wake (SSW) — showing that the curve has slider-like tendencies rather than having a traditional topspin. For more on the discussion of gyro spin on curveballs, check out our own Zach Hayes’ piece from last week.

By increasing the usage of the curveball, his Stuff+ should theoretically increase, especially the new update that considers the benefits of gyro spin. However, his other three pitches — sinker and four-seamer specifically — probably don’t grade too highly. The curveball itself lacks downward movement, meaning it doesn’t tunnel well with fastballs toward the top of the zone. And since his sinker now displays greater vertical movement, it will not generate weak contact at the bottom of the zone when thrown in tandem with the breaker. Additionally, Luzardo’s four-seamer now has a movement profile that falls along the “line of normality”, serving as a possible explanation as to why his four-seamer has been so ineffective. In short, our first conjecture is likely ineffective since his other pitches are fairly poor.

This brings us to our other argument — basing it on the sinker. Last year, Michael Augustine wrote a piece on Fangraphs on how Luzardo could generate more whiffs into his game. It was based on a study presented at SABR last year where subsets of particular pitches were formed based on velocity, spin, and pitch movement (pitch f/x). For example, there were three different types of sinkers — SI1, SI2, SI3 — based on the horizontal and vertical movement. Overall, there were 30 different pitch types for each handed thrower. Some of the findings included what particular pitches affected another’s swinging strike rate, pop-up rate, ground ball rate, and exit velocity. For a left-handed pitcher, one of the best pairings that were found was an SI3 and CU3 for increasing swinging strike rate on the former pitch subtype. As Augustine mentions in his piece, Luzardo’s breaker matched perfectly with the CU3 classification but the lefty’s sinker was short an inch of vertical movement to fit with SI3.

A year later, Luzardo’s sinker now has a spin axis of 10:30 out of the hand, 30 minutes more than what it was back in 2019, but more importantly has added that extra inch of lift while keeping the same amount of arm-side run, finally fulfilling the SI3 classification. The problem? Luzardo’s curveball has a completely different movement compared to two seasons ago, so it’s not a CU3 anymore — and therefore he once again finds himself unable to attain that ideal pairing.

Luzardo’s swinging strike rate has dipped to 12.8% this season, the lowest figure he’s posted across his brief career. With fewer swings and misses, it’s easy to see why the left-hander’s pitches thrown per plate appearances (3.83 P/PA) and two-strike foul percentage (19.6%) are also at career lows. Throwing more pitches with the inability to put hitters away are easily discernible symptoms of his escalating walks and home runs given up. The solution, however, is not nearly simple. It will likely require building a cohesive repertoire, something that Luzardo currently does not have. That is a lot of work and it’s something that will have to start during his current stop at Triple-A.

Photo by Cody Glenn/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)

I’m sure he’s a great hold in dynasty leagues, but I’m assuming he should be dropped in redraft formats?

Not so fast my friend. Is he a great hold or a guy you should be trying to sell? That is the question! On a guy with two giant down arrows nest to his name I always think, maybe I can trade this guy and then get him back in a year if he really is lost. Given the dire state of the minors, I think you can probably still get a king’s ransom from the right owner. If that is the case, then you should consider selling. In a redraft he is an easy drop.

The thing that went most wrong was the absurd expectations. There is a lot more to all of this than talent. Oozing talent isn’t nearly as important as Twitter chalks it up to be. Things are very easy being left-handed with a power arsenal but that only goes so far. Those in the prospecting industry never had much faith in Luzardo to be an impact starter. His story has played out very predictably. He is as fragile as they come and the result have never been what people wanted them to be. All this points to a guy that has little aptitude for pitching who got where he is on God-given talent. He has always projected most realistically as an elite bullpen arm. For a guy like this, getting annihilated is probably the best thing for him. If this doesn’t let him know that he needs to improve, then nothing will. I would never put it past him, but he and Sixto were always most likely to go this direction. I can’t think of one without the other. Luzardo had more success, but he also gets to be left-handed and that advantage doesn’t last forever. In the big leagues, they see a lot of lefties that can throw mid 90s. I don’t think you can really analyze such small samples as what you have with Luzardo – check out the minor league track record and it all makes more sense. He is hurt all the time and the more innings he pitches at a level the worse it gets.

That last GIF is a SL. Pitch classification is wild enough that it is pretty meaningless. Interestingly, all of those FB were well-located which you don’t see a lot of. They were all also wall-scrapers and missed being fly outs by a slight margin. Just interesting GIFs is all.