Pitching’s hottest trend is the sweeper. The pitch has grown in popularity the past few seasons, led, as these things often are, by the Dodgers and Yankees. It’s caught on enough that Baseball Savant declared it a distinct pitch classification a few weeks ago.

Accurate classification of pitch types is an inherently messy business (what one pitcher calls a slider, another pitcher might call a curveball, for example), but the Savant data shows the number of sweepers thrown across the game has increased from just a couple of hundred in 2017 to more than 10,000 last year.

If the Twitter feed @MLBPitchClass is to be believed this spring, that figure is sure to increase significantly more in the coming season, and the list of pitchers who have said they are working to add a sweeping breaking ball to their arsenals this spring is long. Zack Wheeler, Jameson Taillon, and Joe Ryan, to name just a few.

Jameson Taillon, new Sweeper Grip. pic.twitter.com/A6MJWrplrx

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) February 27, 2023

A big part of the appeal of the sweeper, besides the mesmerizing aesthetic of a big-bending breaking pitch, is that it tends to suppress production on contact. Like “normal” sliders, sweepers are most useful against same-sided hitters, and they miss bats and allow home runs at roughly the same rates as regular sliders. But when a sweeper is put in play, especially with the platoon advantage, it’s much more likely than a regular slider to be a weakly hit fly ball or infield pop-up, instead of a ground ball. While ground balls can be good, they sometimes turn into singles, and pop-ups, which almost always turn into outs, are even better.

To that point, since 2017, the league’s sweepers have allowed a cumulative .249 weighted on-base average (wOBA). The league’s sliders have given up a .269 wOBA. Much of that twenty-point difference can be attributed to the fact that sweepers allowed a .257 batting average on balls in play (BABIP) because of an average launch angle of 19.6°, while sliders allowed a .284 BABIP and a 12.9° average launch angle.

Onto the Next

The natural order of these kinds of things is that by the time a trend is widely adopted, the innovative leaders have already moved on to the next thing. Pitching is never static. Everything is connected. If a pitcher adds a new pitch to their toolkit, it has an impact on their other pitches. In the case of the sweeper, part of the ripple effect is then figuring out which pitch types go best with it.

Some recent research about pitch tunnelling from Ethan Rendon, Elijah Emery, Will Sugar, and Tieran Alexander, writing at ProspectsLive, has been able to put some numbers to the optimal movement and velocity profiles for certain pitch pairings. According to this work, the best fastball and slider (here, inclusive of sweepers) pairings have at least two of the following:

- 6-14 inches of horizontal movement separation

- 8-16 inches of induced vertical break separation

- 6-11 MPH velocity separation

With the prevalence of big breaking sweepers coming into play right now, an important point to highlight from these findings is that there is such a thing as too much movement separation in a pitcher’s arsenal and the writers offered that separation greater than 18 inches between a fastball and a slider is “borderline unusable”.

That movement separation can come from a big breaking slider, from a fastball with a lot of movement, or some combination of the two. How it’s generated is not the important part. It’s just the separation between the two pitch types that matters. And the same holds true on the vertical movement axis.

So what is a pitcher who finds themselves with too much movement separation to do? I suppose they could work to tone down the break on their pitches, but that seems inadvisable in today’s stuff-driven pitching culture.

The Cutter Bridge

Another option, the ProspectsLive writers suggest, is to incorporate a cut fastball to serve as a bridge between the fastball and the horizontal breaking ball. Corey Kluber, with his before-its-time sweeping breaking ball that no one quite knew how to classify, is perhaps the OG of this increasingly popular approach.

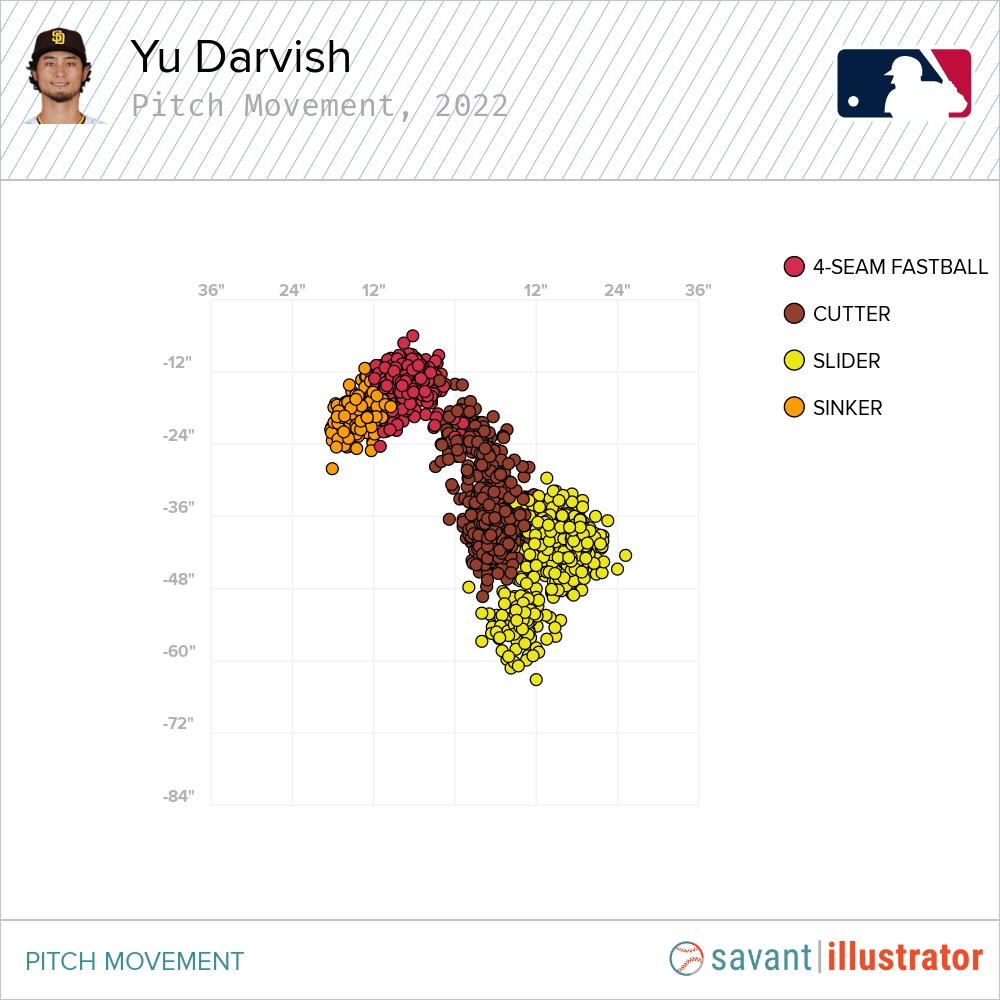

Yu Darvish is another prominent pitcher who uses this tactic because he fails all three of the “optimal” characteristics listed in the research above. The horizontal separation between his four-seamer and slider is more than 22 inches and the vertical difference is almost 19 inches. The difference between his sinker to his slider is approaching 30 inches horizontally and more than 13 inches vertically. The velocity gap is more than 12 miles per hour on average.

What Darvish does though, as you can see in the pitch movement plot below, is fill the space between his fastballs and his slider with cutters. As the ProspectsLive writers put it, “the fastball and slider don’t have to look the same, they just have to look like the cutter, which looks like both of them.”

A cutter can also serve other purposes in a pitcher’s repertoire. Cutters are often less vulnerable to platoon disadvantages than sliders and sweepers, so they can make sense for pitchers who are vulnerable to opposite-handed batters. Moreover, for pitchers with extreme movement profiles, throwing strikes can sometimes be a challenge. A cutter, with its naturally smaller movement profile, can serve as an option that a pitcher might be able to keep in the zone more often.

Such is the case of Seattle’s Matt Brash, a PitchingNinja darling thanks to the whiffle ball movement of his stuff, but also the owner of a 4.44 ERA and a 14.9% walk rate that threatens to relegate him to the bullpen permanently. Naturally, then, Brash has spent this offseason working to add and perfect a cutter with the help of the team at Driveline. This video cut-up really helps make the point about how a cutter can tunnel with both the fastball and sweeping breaking ball to connect them all more effectively together.

The people want Matt Brash cutter updates. #MakeThemSwing2023 https://t.co/g3xl692Mf6 pic.twitter.com/rrfT4XHwGO

— Chris Langin (@LanginTots13) January 13, 2023

With all of that in mind, let’s look at four other pitchers, who, for various reasons, might benefit from experimenting with adding a cutter to their pitch mixes. To identify these pitchers, I used the three criteria about movement and velocity separation described above and then went looking for pitchers on that list that have wider than desirable platoon splits and/or control issues.

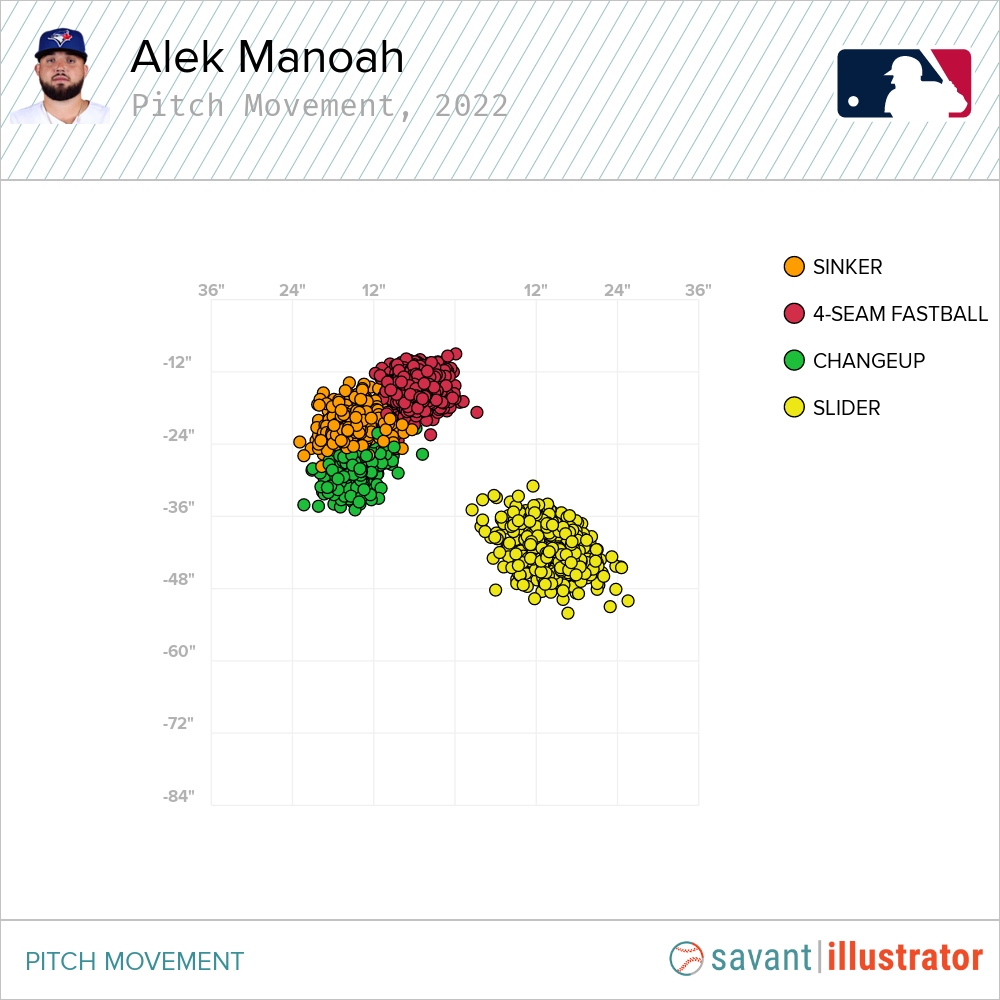

It might be surprising to begin this list with a 25-year-old starter who is carrying a career 2.60 ERA through his first 308.1 career innings. Without question, Alek Manoah has exceeded his prospect expectations with his low-to-mid-90s four-seamer and sinker, slider, and changeup mix. His command of those four pitches had turned out to be better than projected and he takes great advantage of the paired tunnelling effects of his four-seamer and sinker.

Nonetheless, his slider is big, with more than 50% more horizontal break than average at its 81.5 mph velocity, per Statcast. Relative to his four-seamer, the horizontal movement separation of Manoah’s slider is more than 20 inches, and it’s above 29 inches off his sinker. Both of those are well outside the optimal ranges. Vertically, his separation is at the high end of the optimal range and he’s outside the ideal velocity differential at about a 12-mph difference between his fastballs and slider.

Obviously, given his results, Manoah has not been hurt by these characteristics, so the addition of a cutter would not be so much about fixing an issue as it would be about polishing and extending his arsenal.

He’s held his own against left-handed opponents (.307 career wOBA allowed vs. LHB), but his results there are merely a little above average rather than the dominant .216 wOBA to which he’s held right-handers in his career. There is also the matter that he out-performed his run prevention peripherals last year by more than a full run, despite his strikeout rate declining from 27% to 22%.

By PLV, Manoah’s slider is his only above-average offering. Sprinkling in a cutter could be a way to help his other two fastballs play up and also give him a new weapon for left-handed batters, who hit .301 and produced a .361 wOBA against his four-seamer.

I am not a pitching mechanics expert, so I can’t speak to whether Manoah’s low-arm slot and release are conducive to a cutter, but it’s clear he’s skilled at manipulating and spinning the baseball. He’s said that he learned his slider by watching PitchingNinja videos and combined Dellin Betances’ cutter grip with the way Chris Sale manipulates his thumb to change his breaking balls’ shape. That suggests, to me anyway, that Manoah could probably figure out a decent cutter.

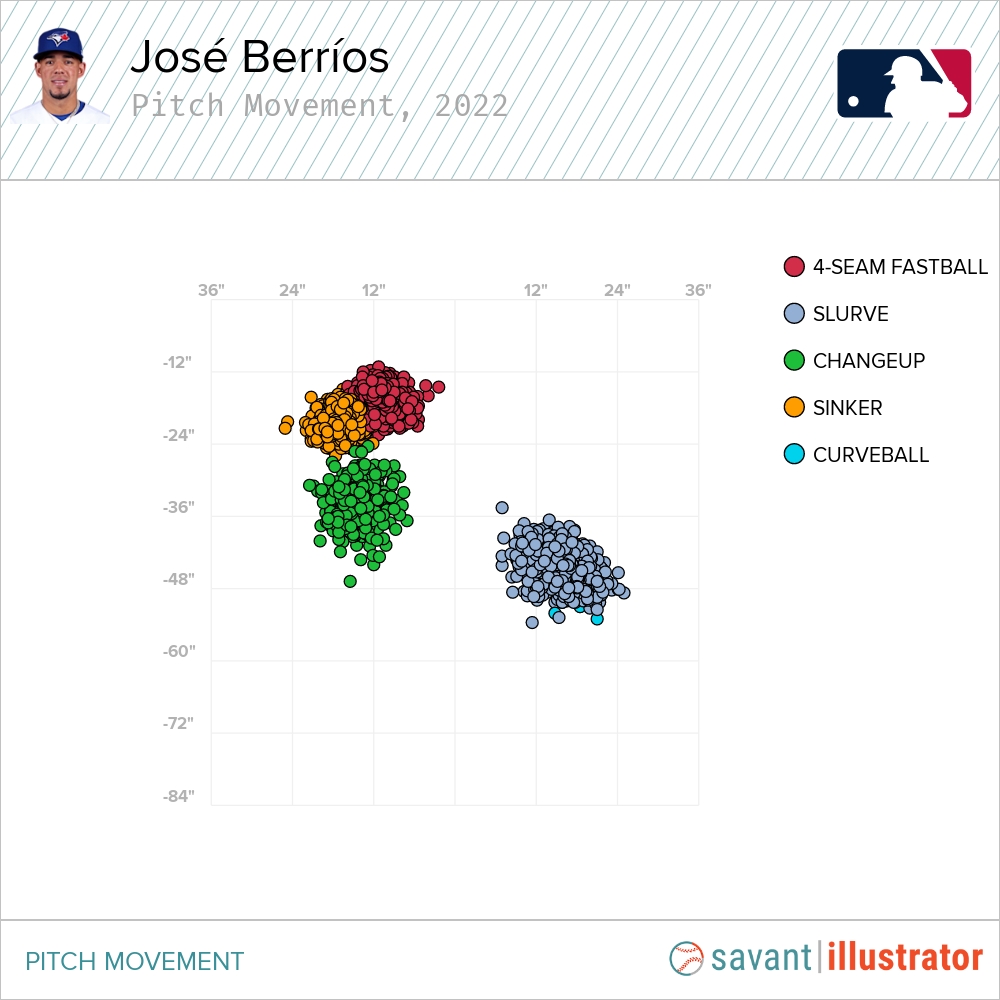

Staying in Toronto, we can include Manoah’s teammate on this list. José Berríos’ first full campaign with the Jays was a disaster and was easily the worst season of his career- save for his initial rookie debut back in 2016. I broke down Berríos in the second half of last year looking for root causes for his sudden change in performance and came away somewhat flummoxed.

His overall stuff was more or less the same as it had been. He was throwing strikes like before. If anything, he was getting more movement on his pitches, especially horizontally, which led me to hypothesize about the rotational nature of his delivery being out of whack (something that he has struggled with occasionally in his career), and more of his pitches, especially fastballs, being in the middle of the plate.

Opposing hitters feasted on Berríos’ four-seamer to the tune of a .349 batting average, a .618 slugging percentage, and a 55.3% hard-hit rate. Opposing lefties did even more damage, slugging .752 (!!!) against it. By Statcast’s run value, his four-seamer was the 8th-worst in baseball (+17 cumulative, +2.2 per 100 pitches).

With these tunnelling findings in hand, we can see that Berríos is well out of the optimal ranges. The separation between his four-seamer and his slurvy breaking ball is more than 26 inches horizontally, more than 18 inches vertically, and about 11 mph on average. His sinker-slurve pairing is upwards of 32 inches horizontal (more than twice the top end of the optimal range) and 14 inches vertical. That makes for some absolutely ridiculous pitch overlays but may be making it too easy for hitters to delineate a fastball from a breaker.

This would not be the first time someone has suggested a cutter for Berríos, but coming off a rough season it might be the right time for him to embrace it. You can see in the plot above how ripe that white space between his fastballs and the breaking ball is for a cutter.

Unlike Manoah, Berríos has a real issue with left-handed batters (.373 wOBA last year), so this suggestion is about fixing a problem. The results he’s gotten with his four-seamer, especially against lefties, scream for him to try something different. He very much needs a different pitch to use in the strike zone, and in the post-sticky stuff landscape, there is little reason to expect his naturally pedestrian four-seamer to rebound.

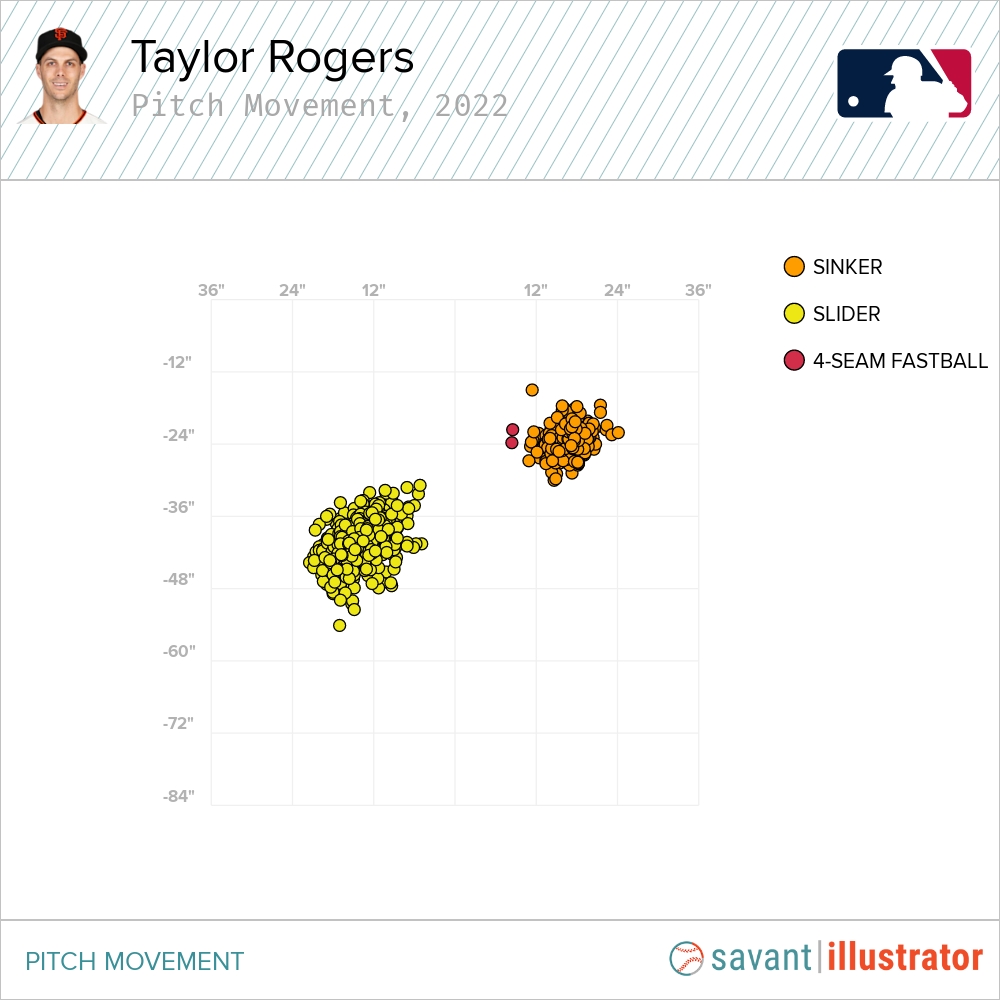

Sticking with former Twins, let’s add a reliever to the list. Again, I’m not the first to suggest a cutter for Taylor Rogers, in fact, FanGraphs’ Ben Clemens did so just last week. Clemens’ argument was largely based on Rogers’ platoon splits. His sinker-slider pairing out of the ‘pen is very tough on lefties (.239 wOBA allowed career), and only league average-ish against right-handed opponents (.310 wOBA). That platoon split was even wider last season (.235 to .342) as Rogers struggled to a 4.76 ERA and -1.70 WPA for San Diego and Milwaukee.

We can complement those platoon deficiencies with the movement separation data we’ve been discussing here. Horizontally, Rogers’ sinker-slider gap is more than 31 inches on average. His vertical separation is within the quality range at 9.2 inches, but his velocity differential is 13.3 mph on average, a couple of ticks more than ideal.

Righties and lefties alike were productive against Rogers’ sinker last season and a cutter (or even just a firmer, gyro-style slider) would give him something he could throw early in counts, to earn strikes in the zone or to generate weak contact and it could help him set hitters up for his sinker and slider. Clemens noted that this would be the same strategy the Dodgers’ have successfully repeated with several of their sinker-slider relievers, including Evan Phillips, Blake Treinen, and Brusdar Graterol.

Let’s close this out with a World Champion who was one of the breakout stars on the mound last season. Cristian Javier, finally entrusted with a regular starting job after a couple of seasons as the Astros’ preferred swingman, pitched to a 2.54 ERA in 148.2 innings across 25 regular season starts and followed that up with another 12.2 dominant postseason innings. All of that earned him a nice, five-year, $64-million contract extension from the Astros

There is nothing complicated about Javier’s approach. He is the proud owner of one of those super-low vertical attack angle fastballs that hitters just can’t seem to square up even though its velocity is only about league average. Javier leans on that special heater a lot (59.9%), especially up in the zone where it can be “invisible” to hitters, and opponents hit just .183 and whiffed 27.3% of the time against last season. By cumulative run value, it was the 10th-most valuable four-seamer in the game last season and our PLV metric had it in the 90th percentile among starters.

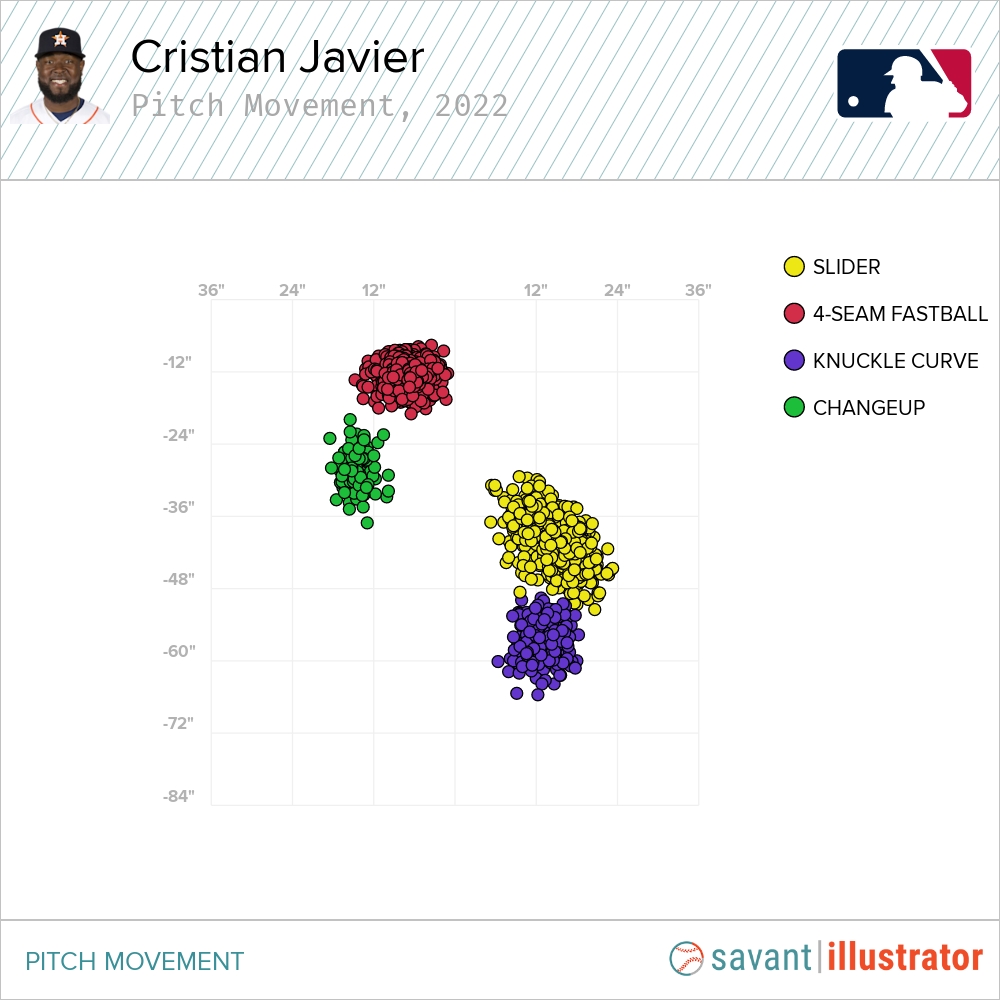

Javier complements his high four-seamer primarily with an above-average, sweepy slider that he throws about another quarter of the time, and that pitch held opponents to just a .121 average and .221 slugging percentage last season. Against left-handed opponents, Javier mixes in a more vertical breaking knuckle curve and a changeup, both of which are below average.

While he’s been more than solid against lefties in his career (.299 wOBA), he does have a 60-point platoon split (.239 vs. RHB), mainly because his curveball and changeup are not standout offerings and both his four-seamer and sweepy slider are more vulnerable to lefties than they are to righties, according to PLV.

More to the theme of this article, Javier gets a lot of two-plane separation between his four-seamer and slider. Both his horizontal and vertical separation are around 22 inches on average and the velocity differential is about 14 mph.

Like Manoah, the idea for Javier adding a cutter has less to do with fixing something, and more to do with sustaining and polishing. I’m not suggesting he replace any four-seamers for cutters. You don’t shelve a pitch like that. But, the occasional cutter as a strike stealer and different look, especially in place of a changeup or curveball against lefties, might be just the thing to keep hitters from getting comfortable with his predictable approach. A cutter might even make his slider more useful against lefties by serving as that Kluber and Darvish-style bridge between his four-seamer and slider.

Photos courtesy of Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Aaron Polcare (@bearydoesgfx on Twitter)