Transport back to about a year ago. Early on in the 2019 season, Yandy Diaz was tearing things up, and the Tampa Bay Rays were once again looking like geniuses after they acquired him from Cleveland. All that he did in the first month of the season was have a .298/.385/.596 slash line with seven home runs, with that seven home run mark being significant in that those seven home runs were just one fewer than the total amount he hit in the 2017 and 2018 seasons in the majors and minors combined. Things were looking great, and with Diaz being one of my personal favorite players, I loved to see it.

Then it all kind of stopped. The first month of the season was definitely the peak of Diaz’s 2019 season, and after that, he went through struggles and injuries, with three separate trips to the injured list in 2019. It didn’t seem like Diaz could ever quite get into a rhythm at the plate aside from that monstrous first month of the season, with the injuries likely contributing to a few of his slumps.

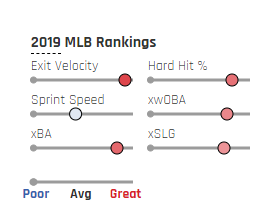

That being said, it wasn’t a bad season for Diaz by any means, his overall 116 wRC+ should show you that, but when you look and see that his 116 wRC+ is nearly identical to his mark from 2018, it may look a little underwhelming, especially because there was so much hype and excitement with him going to Tampa, with the Rays’ superb player development and coaching staffs, that could hopefully fix Diaz’s biggest weakness as a hitter. That weakness, of course, being his high groundball rate. It was obvious at the time, and is still obvious now, that for Diaz to be the most productive hitter that he can be, he would need to lower that groundball rate substantially. It’s even more obvious with just a single glance at his Baseball Savant player page:

That’s a lot of red, especially in terms of exit velocity, which makes it frustrating because as we all know, it’s hard to hit a lot of home runs when you hit so many balls on the ground, no matter how hard they are hit.

However, even with a 51% groundball rate in 2019, Diaz still managed a .476 SLG (on par with a hitter such as Paul Goldschmidt from a year ago), a .491 xSLG, and a .208 isolated power mark, which is generally considered a good place to be as a hitter. Even with a 51% groundball rate, Diaz was still managing a pace of around 30 home runs over the course of a full season. Had he stayed healthy for the course of the whole season, and reached the 30-homer mark, I don’t think we’d be looking at him as a disappointment and we may even be calling the Rays geniuses, even more than we already do. Sure, those marks could still be better, but 2019 was also the first season where Diaz was getting everyday playing time, so these numbers are more than fine for a player’s first real trip through the Majors. All of this also came with good strikeout and walk rates at 17.6% and 10.1%, respectively, with an above-average chase and whiff rate. As is, Diaz is still a valuable player, and also still an intriguing player that I have a lot of interest in.

We tend to focus less on Diaz’s plate discipline and more so on his perhaps underwhelming power output because of his giant-sized arms, and that frustrates us because all we can do is imagine what he could look like as a hitter if only he got the ball off the ground more. Let’s get a little bit weird with this now, and instead imagine him without the giant arms. If we, for instance, had a hitter who was an exact clone of Diaz in every single way, except in the biceps department, what would we think of this hitter? Just doing some basic querying, I looked for all of the hitters in 2019 with at least 300 plate appearances that had a slugging percentage between .460 and .500, an isolated power mark greater than .200, a strikeout rate less than 20%, and a walk rate that was between 9% and 12%. It’s not a perfect way to generate comparisons, but it should give us players that had similar surface-level stats to Diaz a season ago. This query returned five players including Diaz, and those results are below:

| Name | AVG | OBP | SLG | BB% | K% | wOBA | wRC+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yandy Diaz | 0.267 | 0.340 | 0.476 | 10.1% | 17.6% | 0.341 | 116 |

| Jesse Winker | 0.269 | 0.357 | 0.473 | 9.9% | 15.6% | 0.351 | 113 |

| Kyle Seager | 0.239 | 0.321 | 0.468 | 9.9% | 19.4% | 0.332 | 110 |

| Manny Machado | 0.256 | 0.334 | 0.462 | 9.8% | 19.4% | 0.335 | 108 |

| Jose Ramirez | 0.255 | 0.327 | 0.479 | 9.6% | 13.7% | 0.334 | 104 |

Again, this is just a quick and dirty analysis, but there are some interesting names here. Jose Ramirez is a player who is usually being drafted with a top-20 pick and had an extremely strange season a year ago. Manny Machado, even after his just okay season by his standards, is still usually being picked inside the top 60. Kyle Seager is generally being drafted right around the same time Diaz is, and is perhaps a little undervalued himself, and Jesse Winker is still an interesting player without an easy path to everyday playing time, which curbs his fantasy value. Ironically enough, Diaz had the highest wRC+ of the hitters in this group, and I guess the point here is that Yandy is being a bit underrated heading into 2020. Some of that I’m sure has to do with the injury concerns that shortened his 2019 season, but also perhaps because some feel that without a drastic change in his batted-ball distribution, Diaz simply can’t reach his ceiling, no matter how great his batted-ball metrics look. Diaz was already quite productive a year ago though, even with the groundball issues, and if he played a full season and hit those 30 home runs that he was on pace for, I’d bet that he’d be getting drafted much higher. Those that are snagging him around his ADP are likely, in my opinion, to get a pretty nice return from Diaz this season, whenever this season actually does start. Diaz also offers upside, and if this is the season in which he gets his groundball issues under control, then he could potentially be one of the biggest breakout players this year.

Why do we want Diaz to get his groundball issues under control though? Well, for one, remember the snapshot from above. He hits the ball hard, and that’s reason enough for wanting him to get the ball off the ground. Secondly, and maybe most importantly, Diaz did some real damage on his fly balls and line drives a season ago.

Starting with his performance on fly balls, Diaz, using his Herculean arms, was able to drive his fly balls pretty far. His 341 feet average distance on fly balls places him inside the top-30 of hitters with at least 300 plate appearances in 2019. Going in hand with that, Diaz also posted a strong 94.1 miles-per-hour average exit velocity on his fly balls, which for context, places him right alongside Cody Bellinger from 2019. It also shouldn’t be a surprise that by long fly ball rate, a metric that correlates well to total home runs, Diaz was one of the league’s best from a season ago. With a 30.23% long fly ball rate, Diaz placed inside the top 30 in the league, and well above the 21.58% league average. These are all good signs, and match up with his excellent Statcast snapshot from above.

This is just looking at his performance on fly balls; Diaz looks even better when you add in his line drives. Diaz’s 98.7 mph average exit velocity on line drives placed him eighth among hitters last season. While Diaz has never had a fly ball rate that matched or exceeded the league average, during the course of his three partial seasons in the majors, Diaz has managed line drive rates that have been at or above the league average. Combining these two strong results on his fly balls and line drives, we see that Diaz has a 97 mph average exit velocity on his fly balls and line drives, a mark that ranked inside the top 15 among hitters a season ago. Combine that with his strong barrel rate, and average fly ball distance and Diaz has a good baseline to continue to be a productive hitter in the future, and there aren’t many hitters that can provide these strong metrics at the point in fantasy baseball drafts that he is usually being drafted in.

It all comes back to groundballs though, and until he shows that he can get his groundball issues under control, I’m not sure he’ll ever have mass fantasy baseball appeal. Even though he seems to maximize his results on his flyballs and line drives, there may always be a ceiling that he just won’t be able to reach without a significant change in his batted ball distributions. I’m not sure that Diaz ever gets to that point, so that may lead to questions about how much can he improve, and if 2019 was going to be the best we ever see from him.

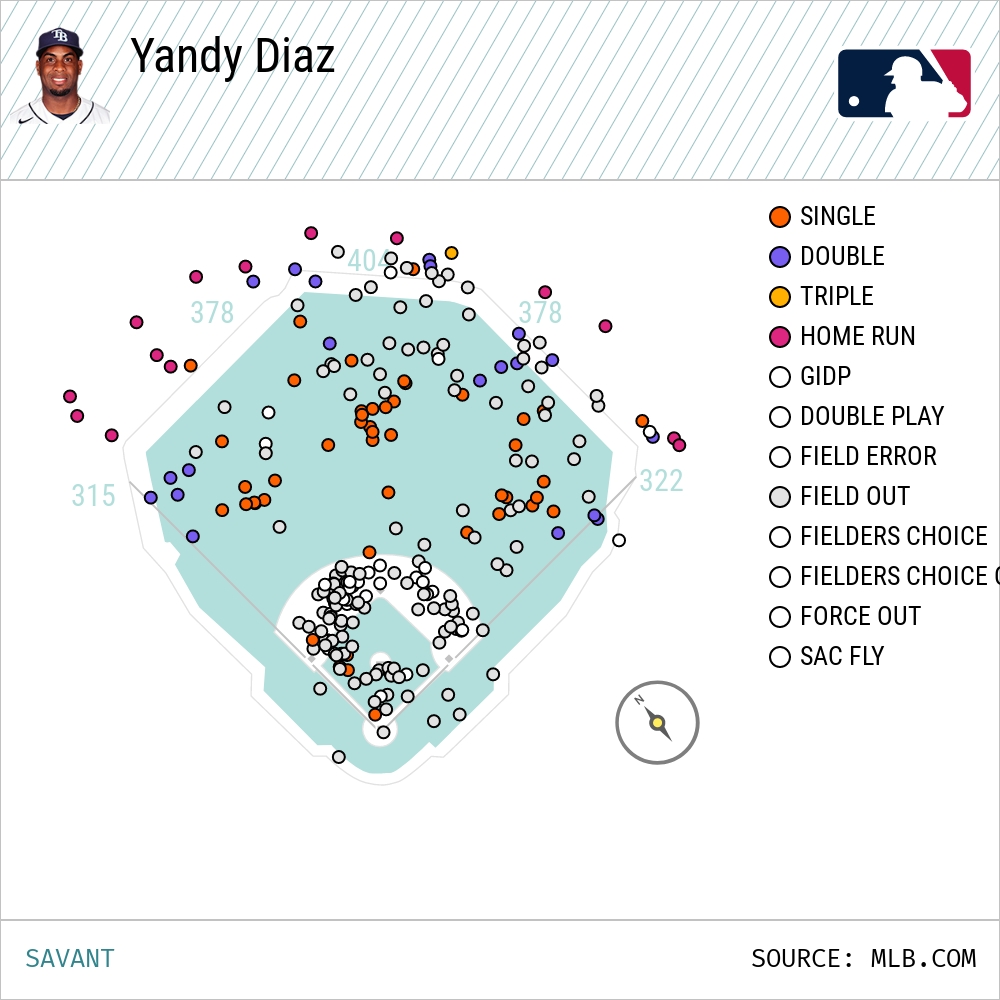

I think Diaz can still get better results with an identical batted ball split, but it’s not necessarily a change I would expect him to make, nor one that I would exactly recommend. Looking at Diaz’s spray chart, you’ll see that he does a good job of spraying the ball all over the field:

Diaz, however, had his best results on fly balls and line drives come when he pulled the ball:

| Batted Ball Type | SLG |

|---|---|

| Pull FB | 2.500 |

| Cent FB | 0.563 |

| Oppo FB | 1.125 |

| Pull LD | 1.909 |

| Cent LD | 0.710 |

| Oppo LD | 1.000 |

| Pull FB+LD | 2.158 |

| Cent FB+LD | 0.660 |

| Oppo FB+LD | 1.054 |

The caveat here is that this is still a small sample of batted balls and maybe isn’t the most reliable, but you can see that Diaz was at his best last season when he was pulling the ball and that 1.909 slugging on pulled line drives was the second-best mark among all hitters last season. Looking at two metrics from Baseball-Reference, tOPS+, and sOPS+ and doing some play indexing, I compared Diaz’s results on pulled batted-balls to all other right-handed hitters in 2019. Diaz’s tOPS+, a metric used to compare a player’s OPS split to their overall OPS, on pulled balls is 234, and his sOPS+, which measures a player’s OPS split compared to the rest of the league in the same split, is 132. Both of these metrics have Diaz towards the top of the right-handed hitter leaderboard, more specifically, he is inside the top 30 in both leaderboards, which further shows how good he was when he pulled the ball a season ago. Perhaps if Diaz took a more pull-heavy approach, he wouldn’t necessarily need to hit fewer groundballs, as he could maximize his damage even more by hitting more pulled fly balls and line drives, which are where he gets his best results. This would be a risky change for Diaz to make, and I don’t think he needs to make this change, as it may lead to some negative side effects, such as more pulled ground balls which could lead to a lower batting average, and BABIP, as well as whatever mechanical issues may come from such a change as well.

So, now we’re once again back to the most logical way for him to get better being to get more balls off the ground. I even ran the numbers to see what type of damage he could do with just a league-average fly ball rate of 22%, and maintaining his 33% HR/FB rate. I almost hate to show this, as it even gets me a little mad that we may never see this, but the results are very good. The first table shows what Diaz would have been expected to do in 2019 with a league-average fly ball rate:

| G | AB | BBE | FB | FB% | GB% | LD% | HR | HR/FB% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual FB% | 79 | 307 | 250 | 43 | 17% | 51% | 26% | 14 | 33% |

| LG AVG FB% | 79 | 307 | 250 | 55 | 22% | 46% | 26% | 18.15 | 33% |

Assuming a league average fly ball rate and Diaz maintaining his 33% HR/FB%, Diaz would have been expected to hit about 18 home runs in his 307 at-bats, and his 250 batted ball events. The next step is then to take the HR/AB and HR/BBE rates and apply them to a full season’s worth of plate appearances, batted-ball events, which for simplicity sake, I applied to 500 batted-ball events and 600 at-bats. The results are below:

| HR/BBE | BBE | Pace/500 | HR/PA | PA | Pace/600 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual FB% | 0.056 | 500 | 28.0 | 0.046 | 600 | 27.4 |

| LG AVG FB% | 0.073 | 500 | 36.3 | 0.059 | 600 | 35.5 |

You can see that with a league-average fly-ball rate and a constant HR/FB%, Diaz would have been on pace for around 35 home runs over the course of a full 2019 season. Yes, that pace looks juicy, and this is perhaps an unrealistic and simplified way of looking at things, but this is just a way to show that Yandy is already pretty effective and efficient at turning his fly balls into home runs. Even with his low fly ball rate, he still was managing a pace of around 30 home runs over the course of a full season. That’s still pretty good!

This brings me to my main point: While I would definitely agree that he would be better off with fewer groundballs, it’s not necessarily bad to be a heavy groundball hitter, as long as that hitter is able to maximize the damage that they do on their non-groundballs, which Diaz did for the most part last season. This is essentially what Christian Yelich did during his MVP season in 2018, as he was always a heavy-groundball hitter that we called upon to change, it is significant to note that 2019 was the first season in Yelich’s career where his groundball rate dropped below 50%. Yelich is a good example of a hitter still being productive despite a high groundball rate, and Diaz should be in a position to continue to hit the ball hard and far in the air, as evidenced by earlier analysis, so I do not necessarily believe it is as crucial for Diaz to get more balls in the air for him to get good results. Don’t get me wrong, it would be nice, but a high groundball rate for a hitter like Diaz isn’t exactly the death sentence that it would be for other hitters.

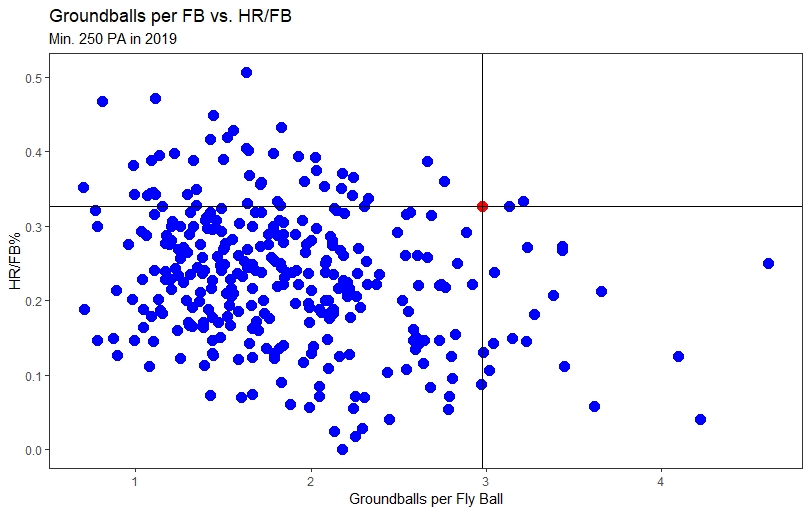

To further show that Diaz was able to maximize his performance on fly balls, I calculated the rate of groundballs hit per fly ball for each hitter with at least 250 plate appearances in 2019 and compared those rates to their HR/FB rate, and graphed those results. Diaz is the point in the red:

Diaz hits nearly three ground balls per fly ball, a rate that is the 20th-highest among hitters in this group, yet he still has a strong HR/FB rate, which while not the best, is nearly ten percentage points higher than the league average, and a rank that places him inside the top 50 of the 321 hitters in this group. The horizontal and vertical lines that intersect at Diaz’s data point are there to show that despite the high groundball rate, Diaz is pretty unique in his ability to turn fly balls into home runs. As it turns out, there are only two other hitters, Garrett Cooper and David Bote, that had a higher rate of groundballs per fly ball, but also a similar HR/FB rate to Diaz. If I had to pick one of the three to continue to be able to maintain this profile in the future, I would pick Diaz, as he is the hitter that is best able to hit the ball hard.

The final area I wanted to analyze regarding all this talk about groundballs to fly balls and HR/FB, is how many other hitters out of these 321 are in a similar boat to Diaz. Meaning, who are the other hitters that have a higher-than-average groundball rate, but the effects of that high groundball rate are less because they hit the ball super hard and turn a lot of their fly balls into home runs? To do this, I looked for all of the hitters that had a groundball rate greater than 46%, a barrel rate greater than 10%, a hard-hit rate greater than 40%, an average exit velocity greater than 90 miles-per-hour, an isolated power mark greater than .200, a HR/FB rate greater than 30%, and finally, a rate of groundballs per fly ball that was greater than two. All of this filtering and querying returned me six other hitters in addition to Diaz, and are in the table below:

| Player | HR/FB% | GB% | GB/FB | SLG | ISO | BRL% | Hard-Hit% | AVG EV | wRC+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eloy Jimenez | 39.20% | 47.6 | 2.03 | 0.513 | 0.246 | 12.8 | 47.9 | 91.0 | 116 |

| Trey Mancini | 36.50% | 46.3 | 2.24 | 0.535 | 0.244 | 10.3 | 42.7 | 90.3 | 132 |

| Shohei Ohtani | 36.00% | 49.6 | 2.76 | 0.505 | 0.219 | 12.2 | 47.1 | 92.8 | 123 |

| Javier Baez | 34.10% | 50.4 | 2.24 | 0.531 | 0.250 | 12.7 | 43.6 | 91.0 | 114 |

| Yandy Diaz | 32.60% | 51.2 | 2.98 | 0.476 | 0.208 | 10.4 | 44.8 | 91.7 | 116 |

| J.D. Davis | 32.40% | 46.0 | 2.13 | 0.527 | 0.220 | 11.4 | 47.7 | 91.4 | 136 |

| Jose Abreu | 31.70% | 46.3 | 2.19 | 0.503 | 0.219 | 12.8 | 48.2 | 92.1 | 117 |

It may be a busy query, but it does return a group of extremely solid hitters. Like Diaz, the other six hitters in this group are able to work around a higher-than-average groundball rate, and are able to maximize their results when they do hit the ball in the air, and turn a good amount of those fly balls into home runs, and they are able to do it by consistently hitting the ball hard, and barreling up the ball, which is definitely a good strategy to try and follow for all hitters.

Ultimately, what I think we need to keep in mind is that despite the high groundball rate and the injuries, Diaz was still a productive hitter in 2019, even in the power department, and I think we would remember that a lot more had he not been injured for a lot of it. Sure, he didn’t get the groundball rate down like we all wanted him to. Despite that, he still hit home runs at a close-to-30 pace over the course of a full season, and while he could have been pushing a 40-homer pace with just a league-average fly ball rate, 30 home runs with good plate discipline and a low strikeout rate should be very much welcomed into fantasy lineups. Diaz was able to manage this by being pretty efficient with the balls that he kept off the ground, with strong exit velocity, fly ball distance, and barrel rates. I get that groundballs stink, but they stink less for a hitter like Diaz who has such a strong batted-ball profile. Assuming that Diaz is able to maintain this profile in the future (something that shouldn’t be too difficult based on his giant arms), he should still be a productive hitter, even with a higher-than-expected groundball rate.

Photo by Cliff Welch/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Michael Packard (@designsbypack on Twitter & IG)

Matt,

Great article; thanks.

Looked at picture and LMAO. Tell Yandy his left hand placement is f’d and that it is causing his bat to not have natural follow-through lift. He need the barrel to be running across his hand, as shown with his right hand. In addition, he needs to get off the knob a bit – it’s buried in his palm too much….. Simple change, but will result in significantly more airborne hits.

HA! Yeah, it might be that simple. Glad you liked the post.

It’s funny, as advanced as much of baseball technique has become, there are still players who get into bad habits and can’t/won’t change them. When it comes to hitting, every player should read Charlie Lau’s: Art of Hitting 300. By way of example, for years I’ve watch Eric Hosmer hit worm burners weakly to 2b, because he’s late in his swing. Why, because he’s got so much pre-swing movement away from his “launch” position and does not have a compact swing, all of which leads to often getting late to the ball; he requires extraordinary timing with his swing.

Charlie Lau preached a compact swing, which by necessity requires starting that swing by getting to a quality launch position,leading the swing with your hands and staying connected to your torso. To understand what this means:

– staying connected to your torso is accomplished by being able to hold a towel in your underarm through the swing – exactly the same with a golf swing.

– in a perfect launch position, one’s hands are tight to your back shoulder and far back enough to create reflexive stretch. Your weight is distributed 70/30 to your back leg.

-your swing uncoils with movement to your front foot and your hand begin the swing, leading to a straightening of the arms and a bat being dragged through the hitting zone for a maximum time, before rolling the arms and more often than not releasing the bat with the back hand.

Like in golf, if you are perfect in all that, but your hands are not placed correctly, you’ve essentially built a house on a faulty foundation. To me, based on the picture, that’s what Yandy has done.

Sorry for the batting technique diatribe……..

No need to apologize, I now have something interesting to read!

Once read, you’ll understand the right mechanics of a swing surprisingly well. Enjoy.

FWIW: I read it in 1980 and never forgot its precepts. The year I read it, I somewhat retooled my swing;

hit over 400 in my last year of high school baseball.