With so many young arms coming up and making an impact on their major league rosters this season, I couldn’t fit them all into just one article!

In case you have no idea what I’m talking about, this is a continuation of a piece I published a month or two ago going over some of the new starting pitcher arrivals we’ve seen in MLB this season. In that piece, I went over what these guys currently do well, what they currently struggle with, and what adjustments they need to make to capitalize on their potential.

I’ll be doing the same thing here with a new sample of young arms. These are guys that either weren’t around when the first iteration of this piece was published or were just breaking into the league and didn’t have enough major league data to comb through.

Fair warning, I couldn’t get to every single rookie starting pitcher in the league between these two pieces, but my ultimate goal is to talk about all of them to at least some level of depth eventually.

So, without further ado, let’s look at five more promising rookie starters!

Of all the rookie starters to make their debut throughout the 2023 season, Andrew Abbott was among the most interesting to me based on his minor league numbers entering his debut. He had always racked up a ton of strikeouts from the very beginning of his professional career, but he began 2023 by taking his ability to draw whiffs to an entirely new level.

Breaking camp with AA Chattanooga, Abbott punched out 36 batters in just 15.1 innings (64.3 K%) over three starts before being summoned to AAA Louisville. On the cusp of the big leagues, Abbott continued his dominance, striking out 54 batters in 38.1 innings (34.8 K%).

People were taking notice of his complete mastery of the upper minor leagues, and the hype around him grew to a fever pitch before his MLB debut on June 5th. He’s done just about everything you could possibly ask of a rookie starter following his promotion, posting a 1.90 ERA, 19.8 K-BB%, and .255 wOBA against over 61.2 innings. The raw strikeout numbers have leveled off against the highest level of competition (27.8 K%), but the early results have been fantastic nonetheless.

The thing that makes Abbott so interesting, though, is that nothing in his pitch mix leads me to believe that this is a guy capable of putting up ridiculous strikeout numbers throughout the minors and above-average ones in MLB.

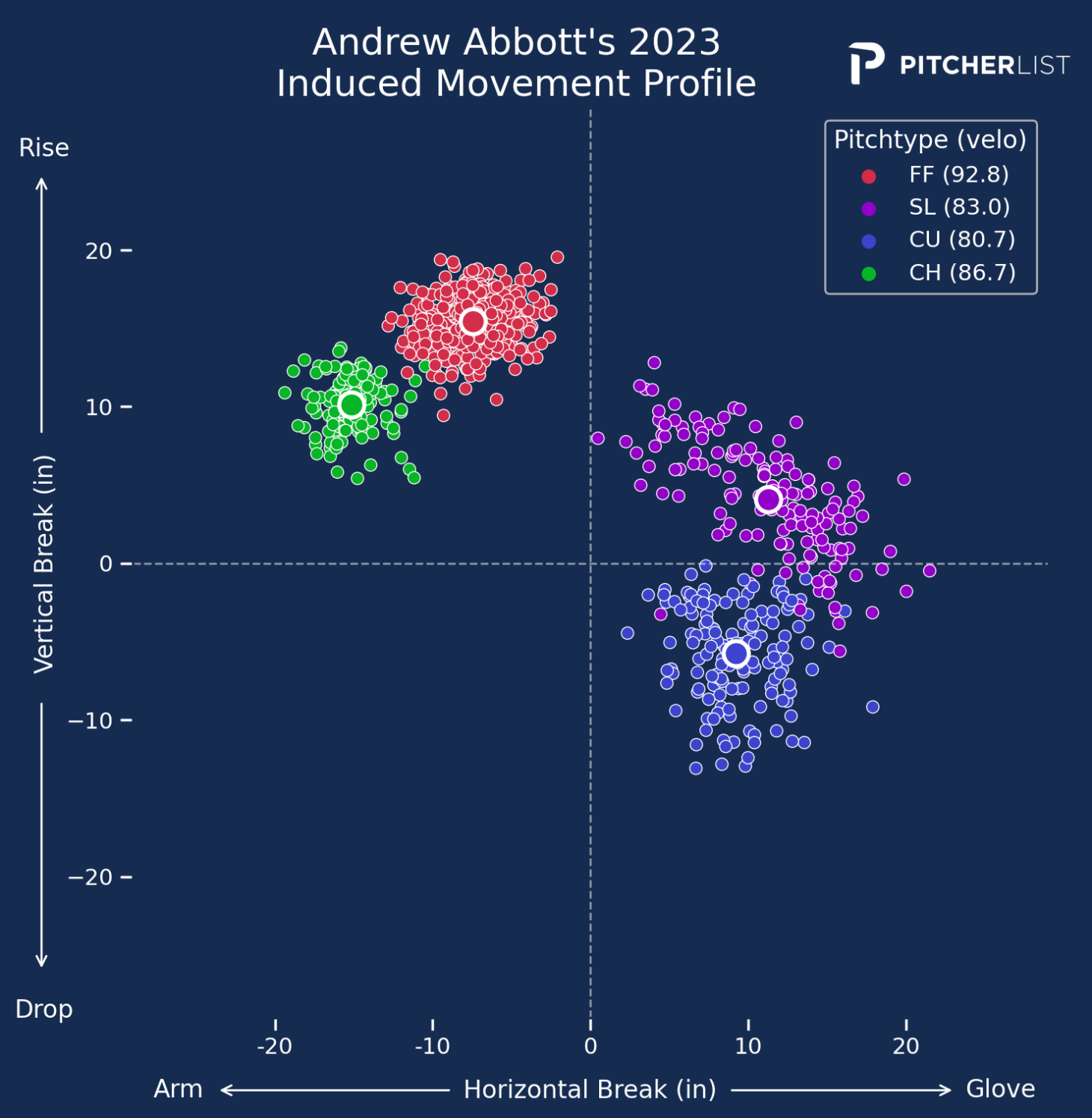

Looking at his arsenal, Abbott works with a four-seam fastball he throws about 50% of the time and three secondaries that account for the other half of his pitches (slider at 18%, curveball at 17%, changeup at 15%). His fastball isn’t particularly overpowering, averaging 93 MPH with 16 inches of ride and 7 inches of arm-side run from a 5.8-foot release height.

None of those specs stand out all that much from his fellow left-handed starters aside from the extra inch or so of ride he gets on it and his above-average extension. Predictably, the four-seamer has been Abbott’s worst offering by results, generating just a 9.9% swinging-strike rate, .314 opponent’s wOBA, and 15.7% barrel rate.

The best results for Abbott in his brief big-league career have come from his secondaries, namely his slider and changeup. The slider borders on a sweeper with its 11 inches of glove-side break, but it comes in hard at 83 MPH and with more ride than your typical true sweeper. Regardless, it’s getting results, generating a 16.9% swinging-strike rate over about 150 pitches.

I suspect part of the reason Abbott’s slider has played so well is partially due to his ability to change the shape of the pitch to cover holes in his total movement profile. The spread on his slider movement ranges from cutter-ish territory (close to the zero horizontal movement line) to something resembling more of a true sweeper (in the 12+ range for horizontal movement).

This seems to add a layer of deception to his breaking balls, even with the slider occasionally bleeding over into the curveball movement profile.

The changeup has also been a nice weapon for Abbott, but it’s got a pretty unique movement profile. He’s throwing it with way more ride than the average left-handed changeup, which is usually a bad thing.

He does, however, get more horizontal run on the pitch than average and throws it 2 MPH harder to an 18% swinging-strike rate, so I won’t argue with the results to this point. This is the pitch I think could be an X-factor for Abbott down the road, but what can he improve on now while he’s on this run in Cincinnati?

It feels odd to discuss improvements for a guy with Abbott’s surface numbers, but there are definitely figures under the hood that indicate his current performance won’t last. His FIP (3.75) and xFIP (4.30) speak to a pitcher due for regression in the immediate future, and there is no doubt that we will see some amount of regression from Abbott sometime soon.

In the meantime, I think the primary area of focus for Abbott should be to devise a more sustainable plan of attack for right-handed hitters. Currently, Abbott has gotten by just fine being a pure fastball/slider guy against same-handed batters, but he’s had to improvise to survive against righties thus far.

Throwing the kitchen sink against righties has yielded fine results to this point (.272 wOBA vs. RHB, .189 wOBA vs. LHB), but there are chinks in the armor. Seven of the eight home runs Abbott has given up have been against right-handed hitters, and he’s had much more trouble putting them away than he has against lefties (16.3 K% vs. RHB, 36.2 K% vs. LHB).

One possible adjustment I think could be beneficial in this case is to leverage his existing ability to manipulate the shape of his breaking ball and repurpose his tighter gyro-sliders into true cutters. Throw them harder and with more vertical break, ideally in the 8-10 inches IVB range.

Because Abbott pretty much refuses to throw the sweeper against righties (rightfully so), he is left with no glove-side movement to leverage against them. Separating his tighter sliders and throwing them harder could allow him to better utilize the horizontal plane instead of relying on elevated fastballs to do all the heavy lifting.

As he currently stands, I think Abbott has the repertoire and stuff to settle in as a solid mid-rotation arm in Cincinnati. His ability to manipulate breaking ball shape and his minor league track record leads me to believe there may be more here, but I don’t think his current level of performance will last long unless he starts making some slight adjustments. He pitches in a tough home park and Stuff+ only gives him one above-average offering (the slider at 104), so temper your expectations.

In a year in which promising rookie starters seem to be popping up left and right, the Guardians have been the beneficiaries of three top prospects making their debuts in Cleveland.

Tanner Bibee and Logan Allen, both of whom I wrote about in the previous iteration of this piece, have been in the Guardians’ rotation since early in the season and have been relatively successful. On June 21, Gavin Williams joined them, bringing with him arguably the highest ceiling of the three.

Posting gaudy strikeouts numbers throughout the minor leagues, the 2021 first-rounder flew through the Guardians’ system to make his debut only just under two years after the day he was drafted. The book on Williams was that he was a well-rounded, polished arm with a standout fastball/slider combo and good enough command to stick as a starter long-term.

Since making his debut, Williams has more than held his own, posting a 3.35 ERA and .309 wOBA across 7 starts. He’s struggled to maintain his strong K numbers from the minor leagues and is walking more guys (8.9 K-BB%), but he’s navigated through danger well enough so far. Let’s take a peek at his pitch arsenal and see what we’re working with.

Williams works with a pretty standard fastball (59%), slider (20%), curveball (16%), and changeup (5%) mix. The fastball averages about 95 MPH with 16 inches of ride and 9 inches of arm-side run. That horizontal movement is about 2 inches more than the average right-handed starting pitcher gets, giving it a somewhat unique shape.

The pitch is running a solid 25.4% whiff rate and 110 Stuff+, but I’ll be interested to see how it plays over a larger sample given its unique shape. For now, it looks like a solid primary offering that warrants the 60/60 scouting grade it was given upon promotion.

Williams also possesses a tight gyro slider, which comes in at 83 MPH with 4 inches of glove-side break. I don’t really love this profile, as it lacks the velocity usually attached to the tighter sliders thrown in the league. With a slider of this nature, you’d ideally want to be at or above 85 MPH for the best results. Stuff+ has the slider at 88, 12% worse than average.

The curveball sits 75 MPH and features 16.4 inches of drop with almost 10 inches of glove-side break, giving it a ton of total movement. That sounds like a good thing, but it kind of works against him here.

The pitch has been too easy to identify for opposing hitters due to its large separation in movement and velocity from his other offerings. Stuff+ has it at an 84, not inspiring much confidence.

The changeup is an extremely intriguing weapon for Williams, coming in at 88 MPH with over 15 inches of fade. Stuff+ loves this pitch at a 142, and it’s not hard to see why. It’s thrown 2 MPH harder than the average changeup and gets an extra inch of horizontal movement. He doesn’t kill ride on it super well, but that’s about the only slight flaw with the pitch.

Williams only throws his changeup about 5% of the time and exclusively to lefties, but I think there is merit to the idea of upping his usage of the pitch. It stacks up to any other changeup thrown by a righty starter in the league on specs alone, and I’d say it could turn into his primary putaway pitch against lefties.

Williams is an interesting case in that he has a good fastball serving as the foundation of his arsenal, but two mediocre breaking balls and a sparsely-used changeup as his secondaries. Having that good fastball is very important, but how his secondaries develop will ultimately determine how high his ceiling will go throughout his career.

I think the quickest path to success is investing a ton of resources into trying to add that little bit of velo he’s missing from his slider and sorting out how he wants to use the changeup. If he can get that slider into the 85-87 MPH range instead of 82-84, it will instantly play much better and give him a lethal breaking ball to pair with his fastball to put away righties.

The changeup, meanwhile, shows real promise as a weapon against lefties. He’s currently relying pretty heavily on the fastball and curveball to put away opposite-handed batters, but I don’t see that being a sustainable approach. Gaining confidence in the changeup and getting a better feel for it will let him reliably attack both planes and become less predictable.

In all, I actually like Williams quite a bit despite some iffy stuff grades, mostly because I think the adjustments he needs to make to become a front-of-the-rotation type arm are not that huge.

He has a solid floor, but seeing if he can throw the slider a bit harder and feel out the changeup can instantly take his arsenal from one good, high-usage pitch to three. That’s the type of young arm you bet on figuring things out eventually.

Around the time the first iteration of this piece was published, Eury Pérez was just making his first few appearances in MLB, so I didn’t get a chance to talk about him in-depth. Eury is now back in the Majors but had a lackluster return. Still, Perez managed to rack up 53 innings between his debut and first demotion, so we still have plenty to talk about.

The 20-year-old starter has done nothing but impress during his brief time in Miami thus far, posting a 2.36 ERA, .292 wOBA, and 20.5 K-BB% over 11 starts. He’s done this with a four-seam, slider, changeup, curveball mix that has yielded extremely interesting results on a pitch-by-pitch basis. His fastball has been hit around a bit, but every secondary he’s thrown has been virtually unhittable.

The takeaway here is pretty clear. Eury’s breaking and offspeed stuff is carrying the bulk of the weight so far. Still, it’s worth looking into each pitch and identifying where there could be improvements or adjustments.

Perez’s fastball looks like it has pretty good specs on the surface. It comes in at a blazing 97.6 MPH with almost 18 inches IVB and 8.5 inches of arm-side run. Nothing in that shape would lead me to conclude that this has been a very hittable fastball, but the 10.7% barrel rate opponents have registered against it would suggest otherwise.

Stuff+ has this four-seamer at a 127, grading out as Perez’s best pitch by a relatively wide margin. It’s not uncommon for hitters to perform best against a pitcher’s four-seamer or their primary pitch these days. Major league hitters have been getting better against fastballs with 16+ inches IVB over the last couple of seasons due to their rising prevalence, so that might have something to do with it.

Shockingly, none of Perez’s slider (100), curveball (92), or changeup (95) are rated as above-average by Stuff+ despite their incredible results.

Looking over their respective profiles, the slider is about as close to a true cutter as you can get, with 0 inches of horizontal movement and 6.1 inches of ride. Only five other starters throw a slider that backs up more than Perez’s, giving it a pretty unique shape that stuff models may not like despite its strong results.

The curveball barely has any vertical drop and actually has more side-to-side movement than the slider, which is pretty weird. The changeup, meanwhile, has a ton of ride (10.5 inches) and 14.5 inches of fade at 90 MPH.

I think when you take a look at the pitch shapes Perez is flashing, it becomes pretty clear why Stuff+ doesn’t love his offspeed stuff but seems to be infatuated with his four-seamer. The fastball has all the classic traits of a good heater: a lot of ride, very good velo, and strong separation between movement on the vertical and horizontal plane. The offspeed pitches, however, feature a variety of counterintuitive specs.

The changeup has way too much vertical movement, the slider doesn’t sweep at all, and the curveball features minimal drop. Each of these pitches works against the norm for pitches of their type, but they still work because Perez throws them hard and throws them often.

One thing I did notice about Perez that I thought was strange was that he has a slightly different release point for his four-seamer and curveball than he does for his slider and changeup. He releases the FF and CU from a 6-foot release height, while the SL and CH come from around a 5.7-foot release height.

It’s a subtle difference for sure, but it looks like he drops his arm slot ever so slightly when he’s supinating for that slider. Small release point inconsistencies aren’t the end of the world, but they can lead to command issues and problems with pitch tipping in more extreme cases.

Aside from cleaning up mechanical consistency, I think it would be beneficial for Eury to play around with the shapes of his secondary pitches to ensure they won’t end up regressing in performance like Stuff+ suggests they will. Introducing a slider with more sweep would make him much more lethal against same-handed hitters, for example.

One of the few bright spots the Tigers have going for them over the last handful of seasons is that they’ve seen a few very intriguing young arms make their way to Detroit amidst a long, arduous rebuild. Tarik Skubal, Matt Manning, and Casey Mize are some former top prospects who have shown flashes of upside to varying extents in their big-league careers.

The latest arm to join that crew, somewhat unexpectedly, is righty Reese Olson. Olson has been consistently ranked around the 10-15 range in the Tigers’ system as a prospect, and he made his major league debut on June 2nd against the White Sox, tossing 5 innings of 2-run ball with 6 strikeouts and one walk.

On the season, Olson has racked up 54.2 innings with a 4.94 ERA, .302 wOBA, and 16.2 K-BB%. Questionable results aside, Olson has some interesting stuff that is somewhat unconventional for a starting pitcher.

His primary pitch is his slider, which he uses 33% of the time. It features 8 inches of horizontal break, more vertical drop than the average slider, and comes in right around 85 MPH. It has also been his best pitch in terms of sheer results thus far, registering a 42.2% whiff rate and .278 wOBA.

His four-seamer comes in just behind the slider at 31% usage. It’s nothing special shape-wise, coming in at 95 MPH with 14.7 inches of ride and 9 inches of arm-side run. Olson also features a sparsely used sinker, changeup, and curveball (18%, 13%, 4%, respectively), but none of them are particularly elite and have generated decent results at best to disastrous results at worst.

Stuff+ sees his slider as his best offering at 136, and his changeup (100) as his only other average or better pitch. It’s not the most jaw-dropping arsenal out there, but I think there is potential to produce better results than the ones Olson has seen to this point.

There’s probably no helping Olson’s fastball shape, and I think you’d ideally want him in a position where he doesn’t need to rely on that pitch at any point. I think leaning even harder into his slider usage and only really bringing out the fastball to speed up hitters who have seen the slider is an approach that may work given his pedestrian four-seamer shape.

I also think there’s some potential in that sinker that is going underutilized to this point. He throws the pitch ever so slightly harder than his four-seamer, and it gets 16 inches of arm-side run with over 10 inches of ride, both of which are squarely above average among sinkers thrown by right-handed starters.

I think if Olson prioritized the sinker as his primary fastball, the unique movement profile it features would play significantly better with prolonged exposure, at least to right-handed hitters. Guys with generic fastball shapes like Olson should seek to leverage another primary offering to do most of the heavy lifting that breaking balls and offspeed pitches can’t do, and I think the sinker might be the answer for Olson.

If he can figure out the right mix between sinker and slider, there’s enough here to be a competent mid-rotation starter. What will really determine how far Olson goes as a big-leaguer is how he ends up using his ancillary pitches, the curveball, and changeup.

Pitching isn’t always just about getting as much IVB as possible on your four-seamer and as much sweep as possible on your slider. Sometimes, leveraging unique movement profiles on your existing pitches is the quickest way to success for young arms trying to find their way. I think Olson might be one of those cases.

Similar to the Guardians, the Mariners have been lucky enough to have several young arms make their way to the majors this season. The earliest and most impactful of them was Bryce Miller, who I talked about in the previous iteration of this piece.

Not long after Miller arrived in the show, his fellow righty Bryan Woo debuted on June 3rd in Texas. It was a particularly bad debut, as Woo only managed to last two innings while giving up six runs on 7 hits and one walk while punching out four against the high-powered Rangers offense. From there, Woo settled in and rattled off a string of impressive outings between June 10th and July 8th.

Woo is a fun arm simply because he throws a ton of pitches with unique movement profiles. Going through them, he features three fastballs (four-seamer, sinker, cutter), two breaking balls (slider and curveball), and a changeup to round things out. Stuff+ likes the sinker (107), slider (111), and curveball (126) the most, and that three-pitch mix can serve as a solid foundation for his arsenal by themselves.

The sinker and slider (which he used to dismantle Eloy Jiménez above) are the two pitches in Woo’s arsenal that have, predictably, yielded the best results thus far.

The sinker comes in at 95.3 MPH with 6 inches of ride and 16 inches of arm-side run, which is pretty much textbook for how you want a sinker to be shaped. The slider is sort of in-between a traditional slider and a sweeper, featuring 6 inches of ride and 13.5 inches of sweep.

I think that two-pitch mix will be there for him throughout his entire career, but much like Reese Olson, how the rest of his arsenal develops will truly determine how high he can go. His four-seamer, cutter, and changeup have all yielded anywhere from average to very poor results, and none of these pitches feature any unique characteristic in terms of either velocity or movement that may differentiate them from other pitches of their type.

Because of this, a lot of the success Woo has in the future will be determined by his usage of these pitches to complement the primary sinker/slider mix. I almost think of a sort of pseudo-Gerrit Cole type of mold here with Woo, leaning heavily on his primary fastball and breaking ball and keeping hitters off balance with the rest of his arsenal.

The most pressing need to develop a reliable third pitch is Woo’s inability to consistently get left-handed hitters out. Lefties are completely annihilating Woo so far.

This makes total sense with a guy who primarily relies on a sinker/four-seamer, slider mix. Righties with that arsenal foundation typically have a hard time getting lefties out consistently because they don’t have anything that moves arm-side to keep them from eliminating the outer half of the plate.

The solution for most of those guys is either to lean into the glove-side movement of their arsenal and incorporate a riding cutter or to incorporate a changeup to open up the outer half.

In Woo’s case, he could go either way. Or, better yet, he could do both. He features both a cutter and a changeup already, both of which are either right around average or not too far from it by most metrics. The problem, like with so many of these young arms we’ve looked at, is that he doesn’t feel comfortable leveraging those pitches against hitters from both sides of the plate quite yet.

Woo is a guy with a great primary fastball and breaking ball, which is pretty much the ideal clay that teams want to be able to mold with a young pitcher. I also think the fixes he needs to increase his overall effectiveness are more immediately attainable than some of those other guys in this piece will likely have to make.

Because of that, I’m willing to bet on him more than a lot of the guys I’ve discussed in these two articles.

Once again, I know this wasn’t a comprehensive list of all rookie starters to make their debuts this season. Emmet Sheehan and Quinn Priester are two guys that I may have to leave until next time, for example.

Still, I hope to cover almost every prominent rookie starting pitcher by the time the season comes to a close. Until then, let’s keep an eye on the guys I wrote about here and see if there are any changes they’re making as the season progresses into the home stretch!