Garrett Cooper is a player I have had an interest in for a while. Maybe perhaps if he wasn’t a New York Yankee for 13 games in 2017, this wouldn’t be the case, but I remembered watching Yankee games that summer and thinking that this guy could hit. Cooper had consistently been a good hitter in the minor leagues, and in 2017 for Colorado Springs, he hit .366/.428/.652 prior to being traded to New York, which certainly isn’t a sustainable stat line anywhere other than the PCL, but perhaps Cooper was being a little overlooked. Sure, hitting in Colorado Springs and the other PCL bandboxes certainly doesn’t hurt hitters, but a hitter must still be doing something right to hit like that. The Yankees’ first base situation at the time was incredibly weak, and Cooper was definitely worth a look in that situation. And guess what, all he did was hit in his short stint with the Yankees. His .326/.333/.488 slash line in those 45 plate appearances is definitely too small of a sample for those numbers to be real, but Cooper was at least showing that he should be a Major Leaguer. This is exactly why I was relieved, although somewhat disappointed to see him traded to the Yankee-infused Miami Marlins that offseason, where playing time was perhaps more likely. With a prime opportunity in Miami, I was ready to see my theory of him being a quality Major League hitter put into action.

Instead, Cooper received fewer plate appearances for the Marlins than he had for the Yankees the season prior. It was because of injuries rather than performance, as Cooper ultimately was the Opening Day right fielder for the Marlins, but his season was ultimately lost to difficulties from a wrist injury that was suffered early in the season from being hit by a pitch. There goes that prime opportunity, and I would have to wait a little longer to test my theory.

Although injuries were still a part of Cooper’s 2019 season, we finally did see him in the Majors for an extended period of time. The results, considering the expectations, were quite good. Cooper quietly posted a .281/.344/.446 slash line in 421 plate appearances, with 15 home runs and 50 RBI to go along with it. It isn’t anything particularly flashy, but it is a nice combination of average to go along with decent power, and Cooper was definitely a useful player. And while I don’t think he’ll necessarily break out and become a much better hitter than he currently is (although he does still have room to get better), he’s a player that I think deserves a little more love. I understand why he’s being drafted a level where he’s essentially free in standard drafts: he’s not overly flashy, he’s already 29-years-old, he hasn’t technically played a full season in the Majors, and in a rare change, playing time is not guaranteed for some Marlins players this season. All of these factors are working against Cooper, but we’re nearly two months into shutdown and I’m not sure what else to do right now, so this is what we’re going to talk about. Let’s take a closer look, and give Cooper some more love.

Let’s start by taking a look at some of Cooper’s splits from a season ago.

| Month | PA | wRC+ |

|---|---|---|

| May | 71 | 111 |

| June | 103 | 164 |

| July | 94 | 101 |

| August | 98 | 59 |

| September | 46 | 156 |

I excluded the month of April from the table, as Cooper only received eight plate appearances when he suffered a calf strain just a couple of games into the season that kept him out until early-May. Overall, Cooper was generally solid at the plate, with June, of course, being the standout month, with a .372/.427/.564 slash line, with a 164 wRC+ that placed him inside the top-15 for that month. In fact, in the first half of the 2019 season, Cooper quietly posted a .306/.375/.473 line, good enough for a 127 wRC+, and comparable to other more highly regarded hitters. Granted it was in just 208 plate appearances, and the early season injury likely took him off of a lot of people’s radars, but this is extremely solid production for a hitter getting essentially, his first real trip through a Major League season.

The month of August obviously sticks out like a sore thumb here though, but there is perhaps an explanation here. He left a late July game with a hamstring injury, and although he didn’t go on the injured list for the injury, he did not start the team’s next two games, and perhaps was still dealing with the injury for a lot of the month, which may explain the struggles, and also perhaps explains why he ended the season as hot as he did, as it’s possible that he was starting to recover as the season came to an end.

Another oddity about Cooper’s 2019 season was how much of a different hitter he was at home in Miami compared to on the road:

| Split | AVG | OBP | SLG | ISO | wRC+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | 0.292 | 0.355 | 0.426 | 0.134 | 114 |

| Road | 0.267 | 0.332 | 0.471 | 0.203 | 107 |

While Cooper wasn’t a worse hitter per se at home in 2019, he indeed was a different hitter at home. It seems as if Marlins Park sapped a lot of his power last season, with Cooper hitting with the slugging output of Adam Eaton at home, but then like Marcell Ozuna on the road. More evidence for that power outage shows up in the drastic differences in isolated power at home and on the road. The league average ISO in 2019 was around .195 in an extreme offensive season, but generally, you would want a hitter to have an isolated power mark above .200, which Cooper did manage to have on the road, but then you wouldn’t want it to be paired with a such a below-average home ISO mark, which Cooper also managed in 2019.

I wanted to find out how often this happened in 2019. To do this, I looked for all of the hitters that had at least 200 plate appearances at their home ballparks in 2019 and then filtered down to end up with the hitters that had an isolated power mark of at least .200 on the road, but then also paired with a home ISO mark less than .170, and then filtered down further to find the cases where the difference in home and road isolated power was greater than 60 points. Turns out, there were 11 total hitters last season where this was the case:

| Name | Home ISO | Away ISO | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel Murphy | 0.141 | 0.209 | -0.068 |

| Garrett Cooper | 0.134 | 0.203 | -0.069 |

| Christian Vazquez | 0.165 | 0.239 | -0.074 |

| Ji-Man Choi | 0.160 | 0.239 | -0.079 |

| Paul DeJong | 0.170 | 0.251 | -0.081 |

| Evan Longoria | 0.141 | 0.228 | -0.087 |

| Khris Davis | 0.123 | 0.211 | -0.088 |

| Jonathan Schoop | 0.162 | 0.266 | -0.104 |

| Luke Voit | 0.141 | 0.263 | -0.122 |

| Willy Adames | 0.100 | 0.225 | -0.125 |

| Kolten Wong | 0.069 | 0.212 | -0.143 |

There definitely are more extreme cases than Cooper’s (hello Luke Voit), but hopefully, this shows how different a hitter Cooper was at home compared to on the road. I’m not too sure what to make of this, it is still too small of a sample of plate appearances in Cooper’s case, but Marlins Park is, of course, one of the least-hitter friendly parks, and even with changing dimensions, it’s still not likely to turn into a hitter-friendly park. Maybe Cooper never hits for much power at home, but I just found this part of Cooper’s season interesting. Ideally, Cooper would see some positive regression in this department in the future, and he can combine what worked well for him at the plate in home games, specifically his strong batting average, with more extra-base power that he showed on the road in 2019 to become a more complete hitter.

Moving on from monthly splits, injuries and where he plays his games, let’s talk more about the type of hitter Cooper is by digging into the batted-ball data, as this is ultimately where Cooper gets more interesting. First and foremost Cooper hits the ball far. I mean, really far. Here are some of his greatest hits (no pun intended) from last season:

Cooper only hit 15 home runs last season, but when he hit them, they sure did go pretty far. Do you care to guess where Cooper ranked in terms of average home run distance in 2019? After seeing those three dingers you might guess top-50, maybe top-20, which would be a good guess, but maybe you think it’s still too optimistic. Turns out, those guesses are still low. How about top-five? I know I was surprised to see that the first time I saw that, and I am still a little surprised as I write these words, but I swear that it’s true. Here’s a table to prove it:

| Player | AVG HR Distance |

|---|---|

| Michael Chavis | 419 |

| Mike Trout | 419 |

| Vlad Guerrero Jr. | 418 |

| Garrett Cooper | 418 |

| Ian Desmond | 418 |

| Ronald Acuna | 418 |

| Jonathan Lucroy | 418 |

| Gary Sanchez | 417 |

| Nomar Mazara | 416 |

| Miguel Sano | 415 |

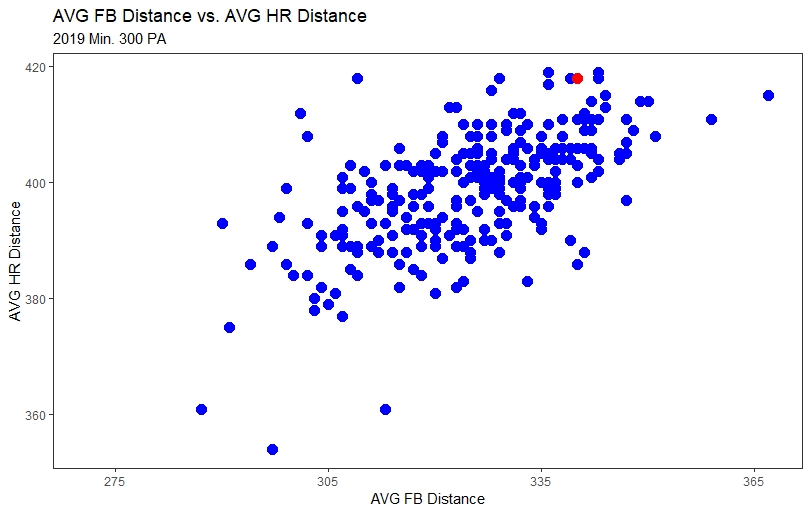

While average home run distance on its own isn’t the most meaningful of stats, it is still a helpful one. A hitter has to be doing something right to hit the ball that far, and I’d wager that Cooper is indeed doing something right here. What if we compare average home run distance to average fly ball distance and see how Cooper fares here? The following graph does just that, and highlights Cooper in red:

We see Cooper’s standout ability in average home run distance, but now we also see Cooper is also good in terms of average fly ball distance, which is generally a more useful stat. While he doesn’t show the same elite characteristics of his average home run distance when looking at average fly ball distance, Cooper is still strong in this department, placing 37th among all hitters with at least 300 plate appearances at 340 feet, and sandwiched right between Shohei Ohtani and Bryce Harper on this leaderboard (with Juan Soto and Nolan Arenado also right behind him). Maybe I shouldn’t be so surprised about this, as Cooper is a lot bigger than I realized, standing at six-foot-six-inches, and is maybe the game’s most unknown giant, as the only hitter taller than Cooper is Aaron Judge, and Giancarlo Stanton is listed at the same height as Cooper. This should give Cooper an inherent advantage over most other hitters in terms of hitting the ball far.

Drilling down even further, we can evaluate Cooper in terms of Long Fly Balls, which if you know me, has become one of my go-to metrics in trying to evaluate the power potential of hitters. I took a two–part look into this earlier in the offseason, and in those looks, I identified Cooper as a player of interest when it comes to Long Fly Ball rate. That’s because on a rate basis, Cooper was one of the best hitters at getting Long Fly Balls. For a refresher, here’s a look at the top-ten hitters in terms of Long Fly Ball rate from a season ago:

| Player | Long FB | Total FB | Long FB % | Total HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miguel Sano | 35 | 72 | 48.6% | 34 |

| Jorge Soler | 50 | 115 | 43.5% | 48 |

| Garrett Cooper | 18 | 46 | 39.1% | 15 |

| Nelson Cruz | 31 | 81 | 38.3% | 41 |

| Franmil Reyes | 35 | 92 | 38.0% | 37 |

| Matt Adams | 22 | 58 | 37.9% | 20 |

| Pete Alonso | 43 | 118 | 36.4% | 53 |

| Christian Yelich | 38 | 105 | 36.2% | 44 |

| Josh Donaldson | 33 | 93 | 35.5% | 37 |

| Trey Mancini | 33 | 96 | 34.4% | 35 |

| League Average | 18.5 | 84.5 | 21.2% | 20.1 |

Cooper shows up really high on this leaderboard, just as he did when we looked at the average home run distance leaderboard. I don’t think many would have guessed that Cooper ranked this in terms of Long Fly Balls, but this maybe shouldn’t be so surprising considering what we now know about Cooper and average fly ball and home run distance, but still, I won’t blame you for being surprised.

The whole reason why Long Fly Balls are important and we should care about them is because they generally lead to good results. That was ultimately what Cooper provided last season when he hit the ball in the air, as he again surprisingly shows up at the top of a few fly-ball related leaderboards:

| SLG | xSLG | ISO | wOBA | xwOBA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.477 | 1.630 | 1.023 | 0.743 | 0.816 | |

| Rank (out of 273) | 20 | 5 | 27 | 19 | 4 |

Cooper’s results on fly balls need to be taken seriously, as these are some truly elite results that again, you maybe wouldn’t expect from a hitter like Cooper, but they’re true.

For additional context, I went looking for some fly ball results comparisons for Cooper, first by filtering to look for the hitters within a similar range of actual results to Cooper, and then filtering down further to look for hitters within a similar range of expected results. This should, theoretically, return some of the best power hitters in the sport, and that’s exactly what happened:

| Player | ISO | SLG | xSLG | wOBA | xwOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson Cruz | 1.383 | 1.889 | 1.953 | 0.958 | 0.961 |

| Miguel Sano | 1.431 | 1.944 | 1.814 | 0.980 | 0.893 |

| Aaron Judge | 1.222 | 1.683 | 1.647 | 0.856 | 0.818 |

| Garrett Cooper | 1.023 | 1.477 | 1.630 | 0.743 | 0.816 |

| Jorge Soler | 1.205 | 1.688 | 1.637 | 0.848 | 0.800 |

| Franmil Reyes | 1.216 | 1.670 | 1.629 | 0.813 | 0.777 |

| Eloy Jimenez | 1.205 | 1.667 | 1.566 | 0.840 | 0.771 |

| Pete Alonso | 1.217 | 1.643 | 1.522 | 0.803 | 0.761 |

Cruz, Judge, Alonso…Cooper? Cooper shows up here in a group of some of the game’s truly best power hitters, including both the American and National League home run leaders from a season ago, and in some cases, Cooper is better than them. Where Cooper “lags” behind is in terms of actual results, which I would guess can at least be partially explained by Marlins Park—as I mentioned before, I think Marlins Park sapped a lot of his power output.

So everything looks good on this front, so then what’s the catch? Why weren’t his overall results better than they actually were? Oh yeah, Cooper’s groundball rate in 2019 was 52.9% last season. That 52.9% rate representing the 17th-highest groundball rate among hitters with at least 250 plate appearances surely takes a lot of steam out of the Cooper hype train and is certainly a bit frustrating. But it’s also a little interesting at the same time. It’s pretty wild that Cooper was able to do all of this with a groundball rate as high as it was last season, as hitters with such a high groundball rate, unsurprisingly, generally don’t hit for much power, and the only hitter with a higher groundball rate than Cooper that had a high slugging percentage was Tommy Pham.

While it certainly wouldn’t be a bad idea by any means for Cooper to get more balls off the ground, seeing Cooper with a higher-than-expected slugging percentage despite a high groundball rate would lead me to believe that he’s making the most out of his non-groundballs, which we did see in the earlier look on the results that he achieved on fly balls. This phenomenon reminds me of Yandy Diaz, a player that I still love despite the high groundball rate. As I mentioned in my earlier look at Diaz, Cooper was one of two other hitters that had a high home run per fly ball rate while also having one of the highest groundball rates in the league. Cooper’s home run per fly ball rate of 32.6% is extremely similar to Diaz’s 32.5% rate and is well above the league average rate of around 24%, and Cooper also didn’t hit many pop-ups last season, clocking in at just 3.3% (7.1% is the league average). While Diaz has a higher average exit velocity than Cooper, they do have similar barrel rates and Cooper actually hits a higher percentage of his fly balls harder than Diaz does which in turn, helps drive Cooper’s superb results on fly balls:

| Hard-Hit FB% | |

|---|---|

| Garrett Cooper | 54.3 |

| Yandy Diaz | 46.5 |

| League Average | 43.3 |

Based on this bit about hard-hit fly balls, and his overall great results on fly balls, hopefully the point is clear that despite a high groundball rate, Cooper was still able to make the most out of his fly balls, and even if his groundball rate remains higher than the ideal rate, he should still be able to be an overall productive hitter.

Cooper is still not without his red flags, however. I mentioned Cooper’s injury issues, and in a shortened season, one injury can really limit how many at-bats he gets. Another area is in Cooper’s high strikeout rate. Cooper did strikeout out nearly 26% of the time last year, a rate that is more acceptable when huge power is coming with it, which Cooper didn’t exactly provide last season. And while I don’t want to just gloss over it, I also don’t want to bombard you with even more numbers in an already long post, but I’ll just say that Cooper did have an above-average rate of looking strikeouts, which should provide some relief that these a lot of these strikeouts aren’t due to extreme amounts of whiffs. And if you want further relief, I will also refer you to the great work on Deserved Strikeout Rates done by Alex Chamberlain of Rotographs that shows that the difference between Cooper’s actual and Deserved Strikeout rate was actually one of the league’s largest at the time. Finally, there are playing time issues for Cooper, as right now he is actually not penciled in as a starting player, although I’m not exactly sure why. I definitely see the appeal of playing Lewis Brinson every day, especially in a season where there won’t be minor leagues, but in terms of who deserves the spot between Cooper, Brinson, and newcomer Matt Joyce, I would say Cooper would be the best option, but I’m not in charge of writing the lineup card, so it’s all in the hands of Don Mattingly, but I am really hoping that Cooper gets the majority of the playing time.

All in all, Cooper doesn’t appear to be the flashiest player, but Cooper quietly delivered a solid, yet unspectacular performance in his first full season in the Majors in 2019. Cooper provided a decent batting average and solid power output to ultimately become a useful player after a long tour of the minor leagues and injury issues that cost him nearly the entire 2018 season. Taking a closer look at the type of hitter Cooper was last season, he turns out to be more interesting than the stat line suggests, as a hitter who is able to hit the ball far at an extremely consistent rate as he shows up at the top of some leaderboards that are usually reserved for some of the best power hitters in the sport. Additionally, despite a super high groundball rate, Cooper was able to take full advantage of his non-groundballs by posting results on fly balls that were among the best in the game. I’d love to see what Cooper can do if he managed to get more balls off the ground, stay healthy for a full season, and with everyday playing time. Cooper appears to have a good baseline for success as a hitter, and this is very encouraging results from a player that ultimately wasn’t expected to do much, and I like to see it.

Photo courtesy of Gregory Fisher/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Rick Orengo (@OneFiddyOne on Twitter and Instagram)