We’re now firmly three years into a Flyball Revolution that has caused swaths of hitters to re-engineer their swings in pursuit of launch angle, barrels, and home runs. Along the way, certain players decided that simply hitting the ball in the air wasn’t enough. They tried to hit flies to the pull-side in order to maximize exit velocity and search for the shortest distance to a home run.

Some players, such as Eugenio Suarez and Kurt Suzuki, achieved long-term improvement by adopting this approach. Others, like Jose Ramirez and Evan Gattis, ended up worse for wear.

Despite these mixed results, fly ball pull rate has become a go-to metric in the fantasy community for assessing hitter improvement. If a batter is hitting more balls in the air to the pull-side, it’s often determined that they’ve legitimately improved, and vice versa.

Unfortunately, there is minimal evidence that hitting more pulled fly balls is a uniformly positive development for hitters. Moreover, there is no guarantee that if a hitter increases their pulled fly ball rate in the short term that the change will stick in the long run.

As a result, analysts and readers should be cautious interpreting increases in pulled fly ball rate as a positive development.

Why Pulled Flies are Good

Let’s start by exploring the allure of pulled fly balls.

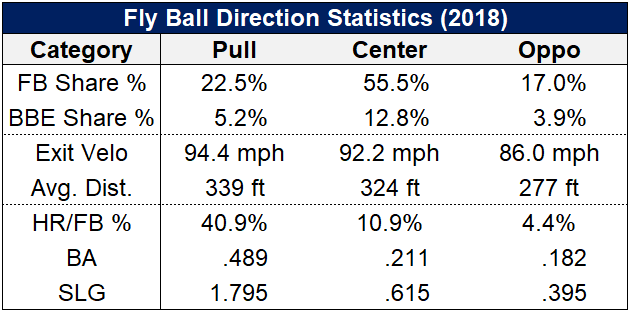

They are, quite legitimately, the ideal result of an at-bat. Although they only account for 22.5% of all flies and 5.2% of batted balls, pulled fly balls are an offensive powerhouse.

For instance, the SLG on pulled flies is 1.795, nearly three times the .615 level of those to center and more than four times the .395 reading to the opposite field. The differentials in HR/FB ratio are even more astounding, with pulled flies leaving the yard at a nearly four times higher clip than center flies and nearly 10 times more than opposite-field flies.

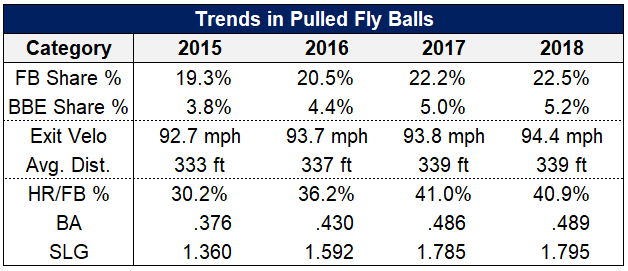

Moreover, hitters have been getting better at inflicting damage when they do hit a pulled fly. In 2015, the average exit velocity on a pull fly ball was 92.7 mph with a HR/FB ratio of 30.2%. By 2018 those figures rose to 94.4 mph and 40.9%, respectively.

Thus, it’s easy to see why the prospect of hitting a pulled fly is a tempting one. Batters, especially those with mediocre raw power, can potentially engineer bursts of outsized production by gearing their approach to hit more pulled fly balls. As a result, hitters have increased their rate of pulled flies from 19.3% to 22.5% of all fly balls and from 3.8% to 5.2% on batted balls over the last four years.

But things aren’t so simple. Just because a specific outcome is desirable doesn’t mean that one should re-invent their approach to achieve it. For instance, think of a football coach calling plays. A deep pass down the sidelines might have the highest expected yardage output of any play call. However, if the coach starts calling that play more often defenses will eventually adjust and neutralize it.

Similarly, hitters that gear their approach to hitting pulled fly balls need to make adaptations at the plate that leave them vulnerable to adjustments. Typically this involves adopting a guesswork approach that sits on specific pitches in certain locations. Pitchers will usually learn these tendencies and begin exposing the various weak points in a strategy predicated on guesswork.

That’s why there is no discernible relationship between pulling fly balls and improving offensive production.

The Evidence

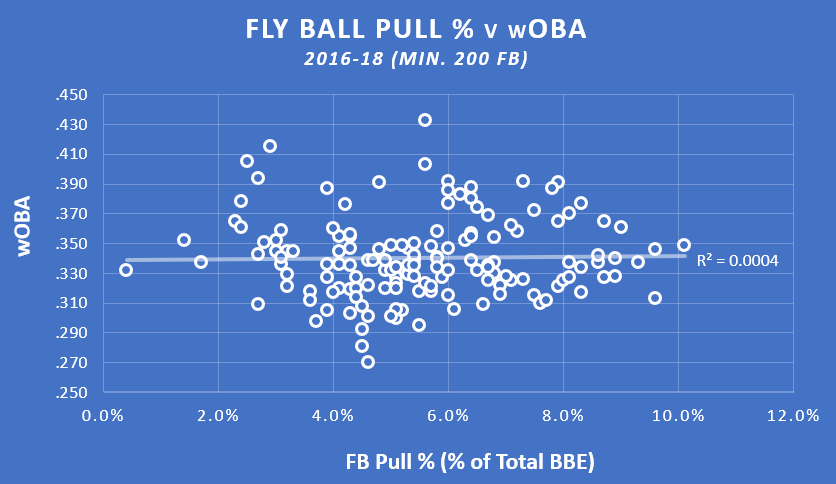

To start the analysis, I gathered data on 147 hitters that hit a minimum of 200 fly balls from one side of the plate from 2016-2018. I then compared their fly ball pull rate (“FBPR”), measured as a percentage of their total batted balls, to their wOBA over that period.

It became immediately evident that there was no broader relationship given the R2 of 0.00. This means that players with higher FBPRs do not create more offensive production and vice versa.

Based on the spread of the dots around the trend line, it does seem like hitters who pulled more flies (those north of the 8.0% level) exhibited less variance in their offensive production. However, they did not achieve the same height of production as players that his fewer pulled flies.

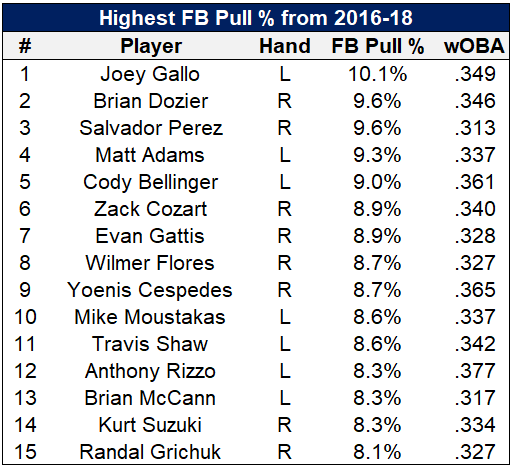

The leader in FBPR from 2016-2018 was none other than Joey Gallo, primarily predicated on the sheer amount of fly balls he hits in general. Interestingly enough, Gallo’s FBPR plummeted from 12.6% in 2017 to 8.2% in 2018 and is down to 6.3% in 2019.

Brian Dozier comes in second and did reasonably well for himself over those years; however, his production has fallen off a cliff the last two seasons.

Zack Cozart is probably the biggest warning sign against adopting an extreme pulled fly approach. While he put together an impressive 24 home runs and 140 wRC+ in 2017, he slumped to an 84 wRC+ in 2018 and owns a deplorable .124/.178/.144 (yes, you read that right—a .144 slugging percentage) batting line in 2019.

Players like Mike Moustakas and Kurt Suzuki represent “wins” for the pulled fly ball approach, as the former turned himself from a below-average hitter to a consistent 30-homer threat. The latter morphed from a terrible hitter to a slightly above-average one, an extremely accretive improvement for a catcher.

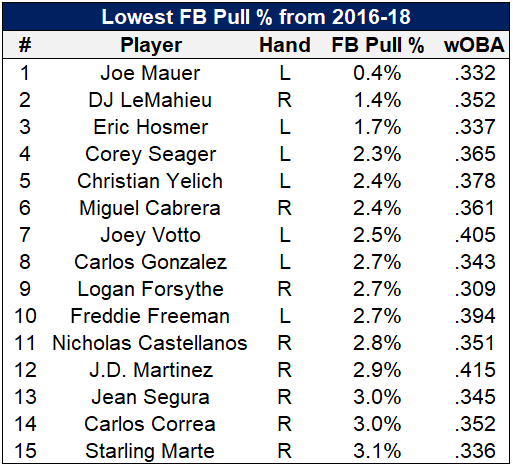

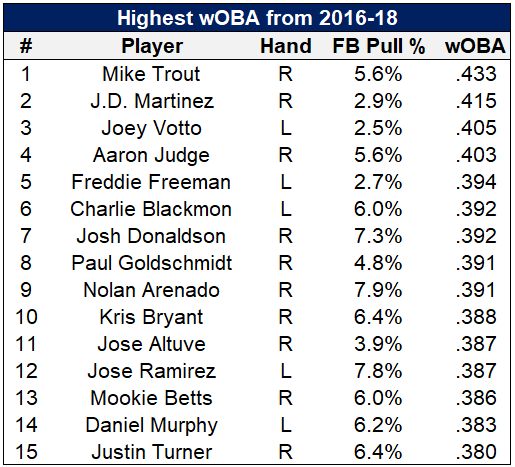

Another interesting finding in the graph is the success experienced by players on the low end of the pull spectrum. Those with a FBPR below 4.0% finished almost uniformly above the trend line, with some very strong showings.

The bottom 15 in fly ball pull rate is littered with some of the games best overall hitters, with Joey Votto, Freddie Freeman, and JD Martinez each charting in the top five of wOBA performers from 2016 to 2018. Meanwhile, Corey Seager, Christian Yelich, and Miguel Cabrera represent three of baseball’s best pure hitters over that span as well.

Of the top 15 players in wOBA from 2016-18, only two—Nolan Arenado and Jose Ramirez—eclipsed the 70th percentile in FBPR. Note that the former plays his home games in Coors Field while the latter has been one of baseball’s worst hitters since last year’s all-star game.

I suspect this indicates that an approach heavily focused on pulling fly balls doesn’t align with a fundamentally sound hitting strategy. Very good hitters have no need to engineer pulled flies because they are capable of taking what the pitcher gives them and doing damage to all parts of the ballpark. This represents an anti-fragile and sustainable long-term strategy.

While this doesn’t mean that certain players wouldn’t benefit from hitting more pulled flies, it means that we should stop universally showering praise on those that do.

Year Over Year

The analysis above showed that players that hit a higher share of pulled flies don’t perform any better offensively. However, what happens when a player experiences a year-to-year increase in pulled fly ball rate? Does a change in pulled fly ball rate lead to a predictable change in production?

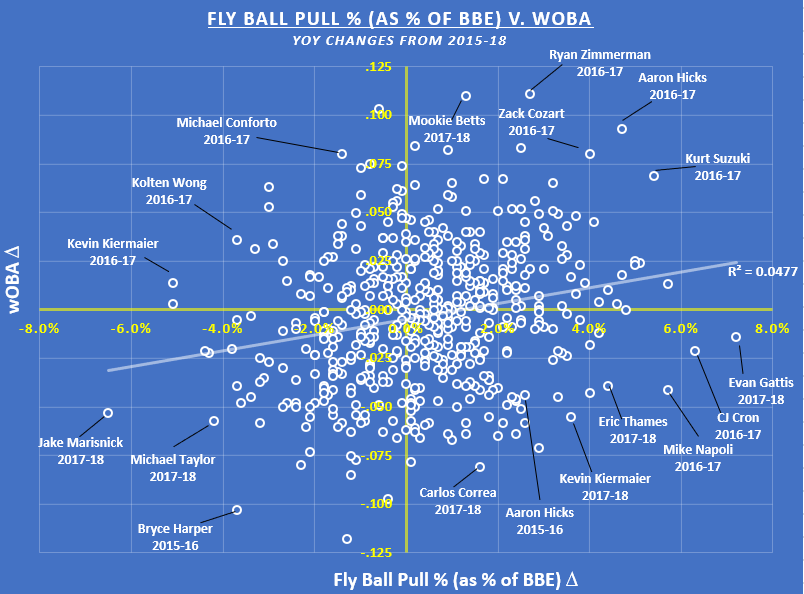

I surveyed 539 pairs of player seasons from 2015 to 2018, analyzing how a player’s year-to-year change in pulled fly ball rate affected their wOBA. Although this analysis revealed a slight positive relationship between the two, the underlying R2 of 0.05 indicates that it’s a weak one.

Moreover, selection bias is likely at play in these results, with pulled fly ball adopters such as Ryan Schmipf being excluded from the analysis because their subsequently poor offensive production caused them to be demoted. It’s likely that the relationship would turn neutral or perhaps negative if these players stayed in the MLB.

Think of the graph this way: The top right quadrant represents instances of player’s leveraging pulled fly balls for improved production, while the bottom right highlights cases where players pulled more fly balls but scuffled at the plate.

It’s evident that 2017 was a banner year for certain players who adopted a heavier pulled fly ball approach. Cozart, Suzuki, and Aaron Hicks each achieved massive wOBA increases while growing their pulled fly ball rate by 4.0% or more. Meanwhile, Ryan Zimmerman improved his wOBA by more than 110 points on the back of a nearly 3% pull fly ball increase.

But for every player who found success with this strategy, there’s someone who struggled—sometimes they’re even the same player. Hicks increased his pulled fly ball rate by more than 2% in 2016, but struggled mightily at the plate. Kevin Kiermaier cut his pulled fly rate significantly in 2017 and improved his production, only to follow that up in 2018 by increasing his pull rate and regressing offensively.

Hicks is an interesting case. While he represents one of the best examples of a player using pulled fly balls to improve; his fly ball pull rate declined from 10.8% in 2017 to 7.4% in 2018 while his overall production held firm. Did pulled fly balls make Hicks a better hitter, or were they a temporary byproduct of his overall improvement at the plate?

Unstable Indicator

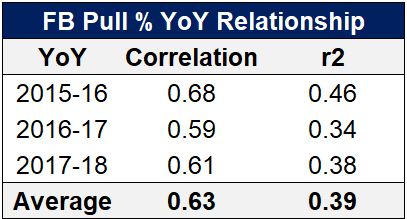

In addition to its lack of a reliable relationship with offensive production, FBPR has another issue: It’s not a very stable indicator.

A player’s FBPR in one year explains roughly 39% of the change in the following year. For context, a peripheral stat like whiff rate exhibits 75% year-to-year explanatory ability.

But much of digital ink spilled about pulled fly balls doesn’t even focus on year-to-year changes. They come in articles that attempt to use a one to two-month change in a player’s FBPR as an explanation for some real, underlying adjustment.

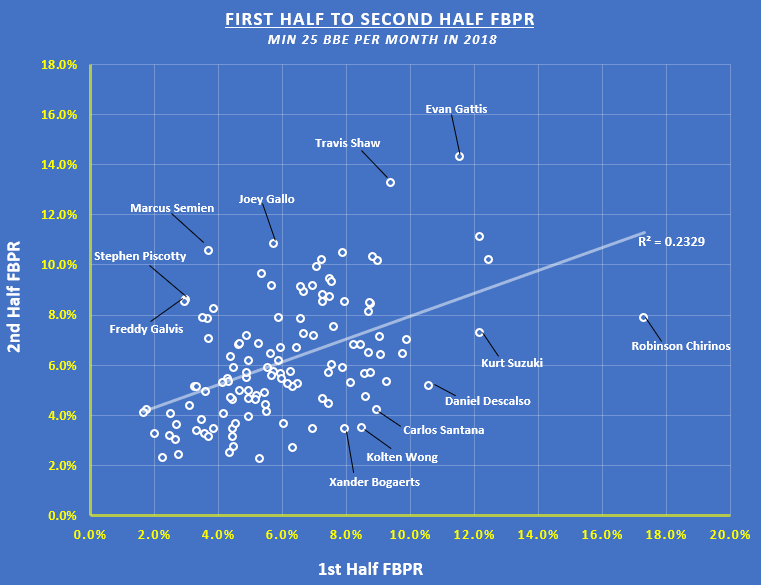

I compared the relationship between a player’s FBPR in the first half of 2018 to the second half. Sure enough, the reliability of the data becomes even worse with a smaller sample size, with FBPR in one half only explaining 23% of the variability in the other half.

Players below the trend line experienced declines in FBPR from the first to the second half, while those above it achieved increases. The further the distance from the line the greater the relative variation from half to half.

Imagine the potentially false FBPR indicators displayed by someone like Gallo. He had a depressed first half FBPR of 5.7%, which might have called analysts to question his approach. Then it increased to 10.8% in the second half, at which point some might have heralded his return to form. Yet thus far in 2019, he has only hit six pulled fly balls for a 6.3% rate, a stretch which coincides with arguably the strongest offensive production of his career.

A Lesson from JD Martinez

JD Martinez is arguably the best hitter in baseball, with his prodigious power and advanced hit tool leading to a .420 wOBA that ranks second in the MLB since 2017.

Martinez is perhaps the most organic hitter in baseball, equally capable of shooting a single up the middle, a double down the left field line, or a home run to right center. His approach is anti-fragile. That is, he gives himself the best opportunity to succeed regardless of pitch type or pitch location.

Every single baseball fan should watch Alex Rodriguez’s August 2018 interview with Martinez regarding his career and hitting approach. If you don’t want to watch the entire 12+ minutes, skip to the 5:50 mark when Martinez begins dissecting his swing approach.

Martinez highlights the importance of matching his bat plane with the ball before it enters the zone. He expands on this by saying he wants to give himself “the largest opportunity of failure and still be right.” What this means is that he wants to manufacture a swing that can result in positive outcomes even when his timing is off or he is fooled by a pitch.

Later in the interview, around the 8:45 mark, Martinez discusses the temptation of trying to hit balls to left in Fenway. He goes on to mention that the times when he does get pull happy he typically mishits the ball and doesn’t achieve the desired outcome.

Hitters who go to the plate with the intention of pulling a fly ball must either guess on pitch type or put a specific type of swing on the ball that gets them further out in front. The issue is that the hitter, instead of being anti-fragile, becomes extremely fragile. If they guess wrong, or if their timing is off, it’s a whiff, pop-up, or weakly hit grounder.

If Martinez guesses wrong, he can still shoot the ball up the middle for a single or down the right field line for a double. A hitter in search of a pulled fly ball is unlikely to achieve the same downside results.

Concluding Thoughts

While pulled fly balls are the most desirable outcome of an at-bat, hitters who change their approach in pursuit of them do not necessarily improve offensively. For every pulled fly success story, there is a flameout. Moreover, hitters do a poor job of keeping their pulled fly ball rate stable, calling into question any analysis that champions short-term FBPR improvement as indicative of a long-lasting change.

As a result, the sabermetric community should develop more nuance in how it approaches this topic. Further areas of research should cover what characteristics pulled fly ball success stories like Eugenio Suarez, Aaron Hicks, and Alex Bregman possess compared to those who failed.

My underlying suspicion is that hitters with plus plate discipline can develop longer-term success with a heavy pulled fly ball approach. Since pulling flies in excess requires guessing on pitch type and location, those who work more favorable counts should have more success ambushing good pitches to hit.

Featured Image by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)

Fantastic. I love articles like this that put some of the conventional sabermetric thinking through an actual analysis. It would be great to see an article that addresses an issue along these lines from the pitcher side as well, though I don’t know exactly what that would be.

Thank you, Ryan!

We have a bunch of stuff brewing on the pitcher front, so stay tuned!

I don’t think you mention that the flyball revolution coincides with juiced balls. It really was not a sabermetric revolution – it just took a few years for the players to realize that holy $#@$ these balls really do fly out of the park!

It is interesting to watch you uncover and hypothesize what is already common knowledge to people who already understand hitting – this is sabermetrics in a nutshell – attempting to teach a computer how to interpret data. I don’t mean that as nasty as it sounds, it is just weird to read about theories that are known already. It is good analysis though and it serves a purpose for a specific audience. It really is too bad that sabermetrics doesn’t embrace the knowledge that already exists.

Pulling the ball does a lot to help EV – everyone knows that. Its why opposite field HR are somewhat impressive. Pulling every ball is certainly a poor approach as it is very susceptible to reasonable sequencing and/or execution. It is an absence of timing if you just do it indiscriminately. I think your analysis right. Its the same lessons that hitters learn before HS is over and the entire reason that pitchers change speeds.

I think you could make some useful generalizations from these ideas – like that poor timing can work over a short stretch, but not over a long run. Additionally, what kind of hitters do you think machines will prefer as they increasingly evaluate players? I think that is the dark underbelly of sabermetrics is all the players that get under/overvalued. Where we currently stand we overvalue peak EV and undervalue consistency. That is the dead-pull approach in a nutshell – great when it works, but the 0-20 stretch with 10 Ks is coming. I believe that the draft is becoming worse overall because it is starting to favor the dead-pull players that can crush poor pitching while less attention is payed to approach and fundamentals – which will be what leads to long-term success. If teams want to pay players to pull FB, then that is what they should do I recon. I think there are a lot of things like that in MLB – things that are cringy to watch and just wrong, but if it keeps you employed and in good standing, then keep pulling those FB. I am sure many players have salvaged a year or two of a career by playing to crude metrics.

E Suarez has a great ability to put a good swing on a ball. Bregman seems to have the good pitch recognition. I can’t speak for Hicks. Just like everything else in reality – different people succeed and fail for different reasons. The reason they are relevant is because they are special and different – you are not going to be able to pin down why they succeed in data. I can see why people will fail sometimes with my eyes, but it isn’t based on batted ball outcomes. I think that we like to think of players as programmable robots, but they are not.

You’re very right – this and some of my other articles come to some very intuitive conclusions. It does seem like the fantasy analysis community wants to forget age-old truisms in hopes of finding a magic elixir that determines whether a player’s improvement is real or not.

A follow-up article will certainly look into consistency. I suspect players with high FB pull inclinations will be much more up and down.

Great stuff. Between this and the “Benjamin Button” article, I have a much better understanding of what may be happening with Jose Ramirez and other pull-happy hitters (both successful and otherwise).