John Means was one of the lone bright spots in an otherwise disastrous 2019 Baltimore Orioles season, but he was also a positive success story for the team after embarking upon what was surely going to be a lengthy rebuilding process. Means was a former 11th round draft pick, and was never considered much of a prospect, but the Orioles ended up with a quality Major League starting pitcher seemingly out of nowhere. It could have even been debated that Means’ inclusion on the roster at all was just due to the team’s overall poor state, with not many other options.

Still, an opportunity is an opportunity, and Means definitely made the most of his in the 2019 season as he cemented himself as a Major Leaguer. Most notable about his 2019 season was his dazzling 2.50 ERA in the first half of the season, which earned him a trip to the All-Star Game, being the team’s only invite.

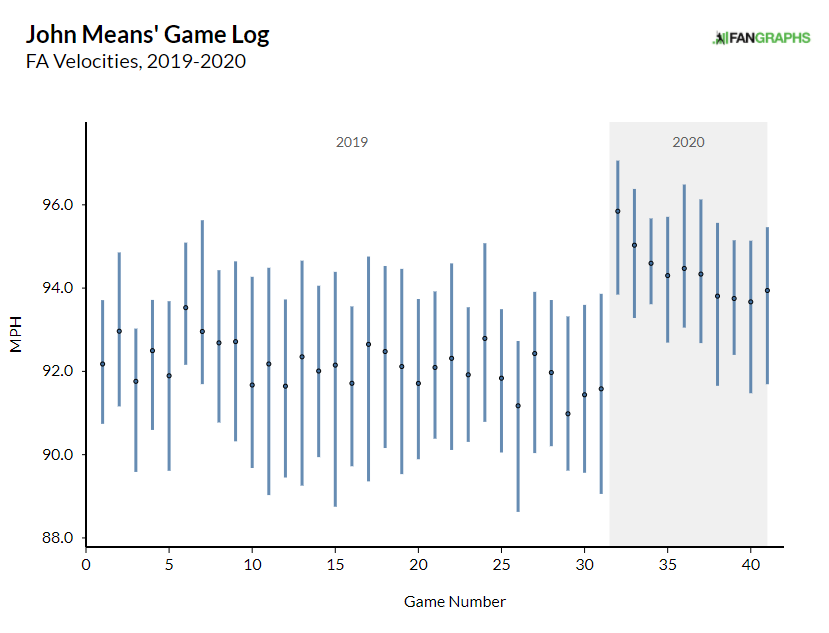

Things spiraled some after that, as Means had a 4.85 ERA in the second half of the season. But with an overall 3.60 ERA for the year, Means was officially on the radar. He was a popular sleeper pick coming into the 2020 season, with fantasy managers hoping to see more of the pitcher Means was in the first half of 2019 rather than the second half. That anticipation had to wait several months, but alas, we finally ended up getting to see him in the year 2020. He was tabbed to face a potent Yankees lineup in his first start of the season, and it didn’t go all that well, but there were still reasons to be encouraged in the form of fastball velocity. Means was pumping gas, with his fastball averaging close to 95 miles-per-hour. While Means didn’t maintain that top-shelf velocity throughout the rest of the season, he still was hurling fastballs at velocities that were previously unseen from him:

So, while Means’ fastball was at its fastest in that first start against the Yankees and it did drop thereafter, the pitch was clearly still faster than it was in 2019. Indeed, Means’ average fastball velocity increased by around two miles-per-hour year-to-year, which was among the biggest gains in the league:

| Player | FF Velocity 2020 | FF Velocity 2019 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yusei Kikuchi | 95.0 | 92.5 | 2.5 |

| John Means | 93.8 | 91.7 | 2.1 |

| Yu Darvish | 95.9 | 94.1 | 1.8 |

| Jacob deGrom | 98.6 | 96.9 | 1.7 |

| Robbie Ray | 93.9 | 92.4 | 1.5 |

We see from this that the velocity bump Means experienced in 2020 was the second largest in baseball. That should be exciting, right? Everybody loves faster fastballs, but for Means in 2020, fastball velocity wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. Rather, Means regressed overall from his 2019 highs, with a 4.53 ERA and 5.60 FIP, which is not good by any means. However, looking at his 3.93 SIERA or 4.25 DRA, there is perhaps something more there. With such stark differences, Means’ season is definitely worthy of a closer look. He only made ten starts, but there was quite a lot going on.

A Rough Start

The hype and excitement that usually comes from a velocity spike was short-lived in the case of Means in 2020. Means struggled mightily out of the gate last season, with an ERA of 8.59, and an also-ugly FIP of 8.59 through his first five starts of the season encompassing the dates of July 30th through August 28th (let’s call this time period the first half of 2020). A big reason for these struggles was due to the fastball. While finding a couple of extra ticks in velocity, Means didn’t quite reap the benefits that would normally be expected from that. Notably, Means wasn’t seeing a jump in strikeouts, which is not the greatest of looks considering he already wasn’t the biggest strikeout pitcher in 2019:

| Split | K% | SwStr% |

|---|---|---|

| Means 2019 | 19.0 | 9.9 |

| Means 1H 2020 | 16.9 | 10.5 |

So, at the start of the 2020 season, Means was actually striking out fewer hitters than in 2019, with only a slight increase in swinging strikes. Instead, Means was getting hit a lot harder. Focusing just on fastballs, Means was just getting pummeled:

| AVG EV | BRL% | SLG | wOBACON | xwOBACON | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Means | 97.3 | 18.8 | 0.609 | 0.481 | 0.456 |

This looks pretty rough. In the first half of the season, Means’ results on fastballs were towards the bottom of the league, and these are obviously not categories that a pitcher wants to be towards the bottom of the league in.

That alone is pretty concerning on its own, but Means’ first-half troubles didn’t stop there. The issues with his fastball seemed to trickle down to his secondary pitches. For Means, that meant it affected his best secondary pitch, the changeup. The changeup wasn’t just the best pitch in his repertoire in 2019, but also one of the very best changeups in the entire league, with a pVAL of 12.3 in 2019, good enough to rank seventh in the league by that metric. However, in this rough stretch for Means at the start of the 2020 season, the pitch had a pVAL of -3.0, which was actually one of the worst changeups in the league in this span. Not having the pitch in its usual lethal state definitely had an impact in his rough start, and without the changeup to play off his fastball, perhaps explains why his fastball was so hittable.

So then, what happened to his changeup at the start of the season? For starters, it appears that his changeup, like his fastball, experienced a velocity spike as well. He added around four miles-per-hour to the pitch last season compared to 2019. Again, this should be good news, but it didn’t quite turn out that way.

It seems that the added velocity impacted the pitch’s movement. For instance, consider that the 81 mile-per-hour version of the pitch in 2019 actually had a good amount of break to it, averaging around two inches more of horizontal movement than average, and towards the top of the league leaderboard. Now, consider that the 85 miles-per-hour version of the pitch in 2020 didn’t break as much, averaging just 0.7 inches more of horizontal movement than the league average. This is important to know because Means’ changeup is one that relies on more break, as 2020 was the second-straight season in which his changeup was the league’s lowest in terms of vertical movement, or simply just called drop. Not that there is anything wrong with relying on break or drop when it comes to changeups, but for Means who clearly relies on one primarily compared to the other, seeing less break without a corresponding change in drop would make the pitch look all the more hittable, which was essentially what happened to Means last season.

The easiest and clearest way to look at this would simply be to look at the pitch heat maps. We should be able to see some clear differences:

What immediately stands out is that Means is missing that big cluster of pitches towards the bottom of the zone in 2020 compared to 2019, that area generally being where changeups should end up. Means was leaving more changeups up in the zone, changeups with less movement, essentially making them look like slower fastballs, which hitters rightfully teed off on. In fact, this can be measured by looking at the pitchers with the highest rate of changeups left in the heart of the strike zone, as defined by Statcast. Doing this shows that Means was in the top-five in the rate of changeups left in the heart of the strike zone, and the highest among starting pitchers:

| Player | Heart CH | Total CH | Heart CH% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyler Clippard | 53 | 144 | 36.8% |

| John Means | 61 | 184 | 33.2% |

| Matt Foster | 45 | 146 | 30.8% |

| Cesar Valdez | 49 | 159 | 30.8% |

| Mike Minor | 66 | 217 | 30.4% |

So, that is clearly not ideal. Means’ changeup was a lot more hittable than in the past, and with his two go-to pitches not working as effectively as expected, Means ended up being extremely hittable overall, but especially so in the early part of the season.

A Grand Finale

A rough start, though, does imply that things get better. They did get better, dramatically so, for Means in the back half of the 2020 season, which ultimately is what makes him an intriguing pitcher coming into this season. After those rough first five starts of the season, Means went on a tear to end the year, with a 2.48 ERA in the month of September. The impressive comeback story for Means begins with the fastball.

We know how rough the pitch was performing at the beginning of the season, as highlighted in the previous section. However, it was a night and day difference in September. It is important to remember that the pitch did maintain its newfound velocity bump. It wasn’t quite 95 miles-per-hour, but still, it averaged 93.5 miles-per-hour in September, which is still notable. That alone isn’t enough, as we saw earlier, but keep that in mind because that velocity works well when paired with what was his biggest improvement to the pitch down the stretch, that being in the location department. Consider the following two fastball heat maps:

Here, we have Means’ four-seamer heat maps in July and August compared to in September. There are differences between the two, the most notable of which being that it appears that Means began throwing more fastballs up in the zone in September. Note the big cluster of red at the center-top portion of the zone in September. Throwing fastballs up in the zone is a popular pitching strategy these days, and Means seemed to embrace that strategy down the stretch. Now, remember the increased velocity. This strategy works a lot better with a higher-speed fastball, and while Means wouldn’t be confused with, say Sixto Sanchez, or Jacob deGrom, 94 miles-per-hour on a fastball is nothing to sneeze at. It seems that this combination of increased velocity and more pitches up in the zone seemed to help Means down the stretch, and the results on the pitch in September were substantially improved compared to earlier in the year:

| Split | AVG EV | BRL% | SLG | wOBACON | xwOBACON | SwStr% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July-August | 97.3 | 18.8 | 0.609 | 0.481 | 0.456 | 10.3 |

| September | 89.8 | 3.7 | 0.250 | 0.277 | 0.200 | 15.7 |

This alone is pretty significant, for sure. However, it shouldn’t be expected for Means’ fastball to continue to be this good in the future. Rather, the point is to hopefully show that first, Means can make an important mid-season adjustment, and second, that this adjustment seems to be a good way for him to continue attacking hitters going forward. There is also a case to be made that just getting more used to actually throwing the pitch more in game situations helped Means gain more confidence on the pitch. It was a long layoff, after all.

It also seems that leaning more into this strategy helped his changeup improve down the stretch. Working up in the zone with high heat seems a good way to get the slower changeup to play up some. After the pitch struggled mightily in the first part of the season as detailed earlier, the pitch went back to being a major part of his arsenal, with a swinging strike rate much higher than previously:

| Split | SwStr% |

|---|---|

| July-August | 9.4 |

| September | 19.0 |

As it turns out, the changeup was actually Means’ best pitch in terms of swinging strikes down the stretch in the month of September. After being the biggest drag in his repertoire in the first half of the season, the pitch returned to being a positive one overall, with a 3.1 pVAL in September, which was among the best in the game, with only the lethal fastball being a better pitch by pVAL for Means in that span.

It appears that down the stretch, Means’ newly faster fastball was actually performing like one, perhaps due to getting the ball more up in the zone, but also perhaps due to just finding more rhythm with it and getting back into the zone after a long and unexpected layoff last year. Additionally, a big part of Means’ September resurgence can be placed upon his changeup bouncing back as well.

The Big Picture

Overall, 2020 shouldn’t be viewed as a complete look at Means. We saw both good and bad from him as he got off to a dreadful start, but finished the year looking like a completely different pitcher. Means also made some general improvements overall that look good and should make him a better pitcher, assuming they hold steady in the future.

First, Means seemed to get even better in terms of command. Means already showed great command in 2019, but he took it to another level last season. He got his 6% walk rate from 2019 down even further to just 4% last year, which was among the best in the game and placed him in the 95th percentile. A cause for this can likely be traced to him throwing more pitches in the zone, as he improved his zone rate by five percent, jumping to 50.7%, and better than league-average.

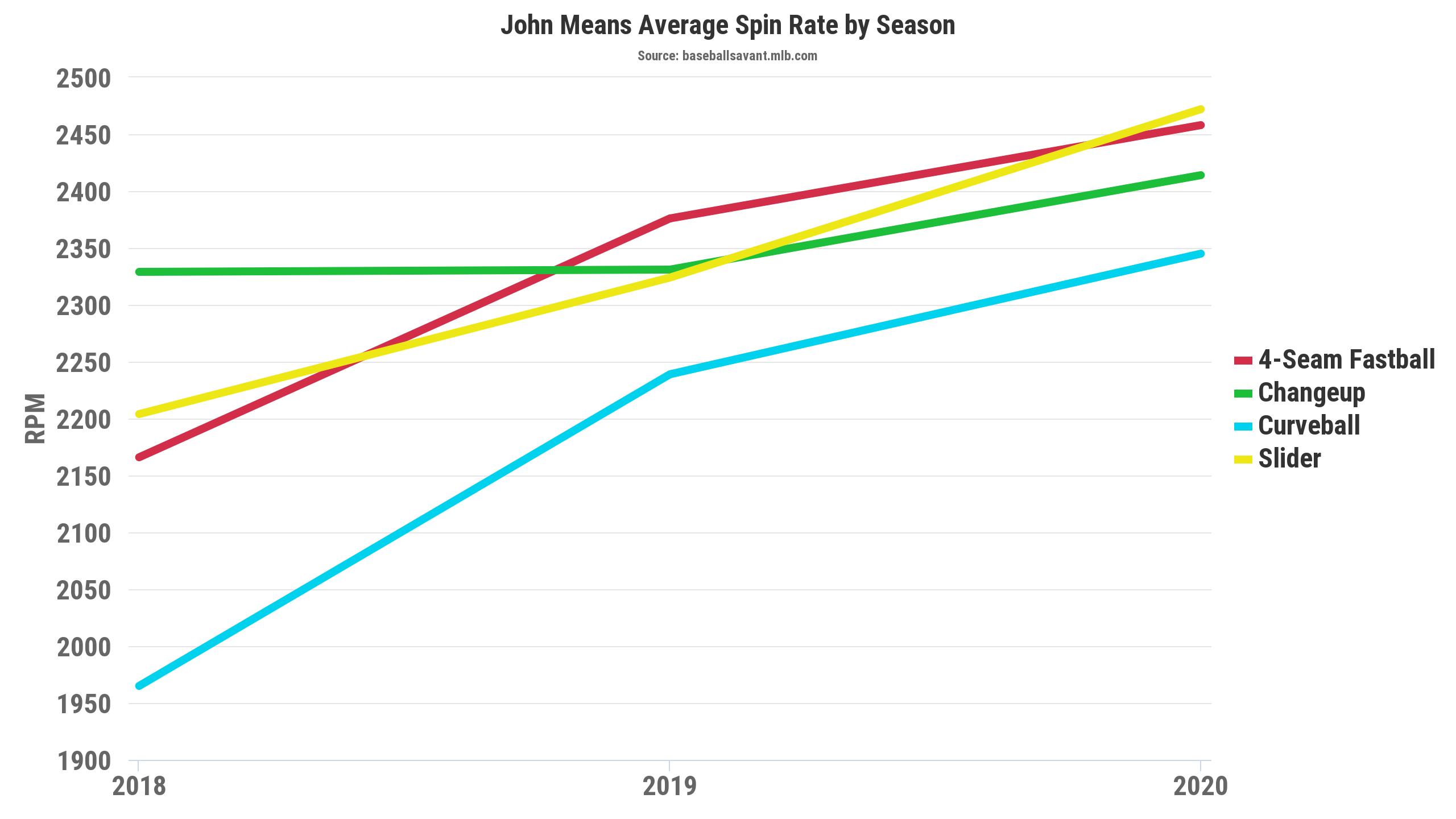

Additionally, the quality of Means’ pitches looks to have improved as well. This sort of goes back to the added velocity on his fastball and the subsequent swinging strike improvements discussed earlier, but Means also did generate more spin on all four of his pitches in 2020:

Also notable is that Means relied on his curveball more, doubling its usage from 2019 to 12.6%. Hitters had just a .188 batting average against the pitch, along with a .188 slugging percentage and .163 wOBA. The pitch was also his go-to pitch for whiffs when he was struggling big time in the first part of the season, although it became less of a focal point when he got his fastball and changeup back on track later on. Still, it is good to see developments in a third pitch and having a more complete repertoire should help him in the future.

The biggest red flag when evaluating Means, however, isn’t the rough start to the 2020 season. We saw that he was able to overcome it and be much better. The one part of his profile that is not likely to leave any time soon is the home runs. Means allowed home runs at a rate of 2.47 per nine innings last season and had a HR/FB rate of 21.8%, both of which were among the highest in the game. Now, it is true that these rates may be a little inflated and Means may have been a bit unlucky. Looking at Statcast’s expected home runs metric, Means had 8.3 expected home runs compared to 12 actual home runs allowed. That difference of 3.8 was the highest in baseball last season, but it should be noted that not only is Means’ home park extremely hitter-friendly but so are the other ballparks in the division he pitches in. Last year was the extreme version of this, as due to the limitations of the schedule, Means started seven of his ten games in American League East ballparks. Assuming a more normal schedule in 2021, Means should get to tour the league’s other parks, so perhaps the home run rate comes down some. Although the elevated home run rate of his profile isn’t likely to go anywhere, it just shouldn’t be as high in the future.

The overall theme surrounding Means is that consistency is going to be critical to his future development. He wasn’t able to shake off inconsistency even in the abbreviated 2020 season consisting of just ten starts, and it was ultimately the second straight season where Means looked like two completely different pitchers in each different half-season. He’s looked dominant or extremely hittable, and we still haven’t seen him deviate much from either one of those profiles. We know what Means can look like at the top of his form, and it is quite an exciting pitcher. It was good to see Means recover from adversity after a poor start to the season in 2020, and hopefully, that nice run to end the year will give him more confidence coming into this season. Means definitely has good and improving skills and we know that he can be a successful Major League starting pitcher. For the future, it’s about Means trying to put it all together, and hopefully, he gets there. Based on the steps forward he took in the back-half of last season, this year could very be the one where it happens.

Photos by Mark Goldman/Icon Sportswire | Design by Quincey Dong (@threerundong on Twitter)