As a fan, there’s often no feeling more frustrating than watching a prospect who’s tearing up the minors struggle at the big-league level. You see the player’s potential to be a lock on the roster for the next half-decade and the stats throughout the lower levels of baseball back it up. And yet, you’re frustratingly tuning in each night to see the player underwhelm again, and you can’t quite understand it.

Since the start of last season, 69 players under the age of 24 have at least 100 plate appearances in AAA and MLB within the same season. 51% of those players have been above league average in AAA and below league average in MLB. That largely makes sense: younger fringe players are more susceptible to struggling than most.

It’s also been well-documented that AAA pitching quality is as bad as its ever been.

Triple-A has been ransacked.

Complete list of Triple-A pitchers with above-average stuff & locations that haven’t pitched in big leagues yet this season (min 50 p/app, 5 IP)David Festa (111 Stuff+/108 Location+)

Shane Baz (108/100)

Andrew Bash (106/101)

Will Warren (101/101)— Eno Sarris (@enosarris) June 12, 2024

Creating a talent disparity between levels is going to make it harder for prospects to adjust at the big league level. They’re facing the best of the best in the majors, and they are no longer adequately prepared for it.

However, some are able to break through and succeed immediately. 13% of my original player sample had a 100 or better wRC+. 100 plate appearances aren’t enough to fully determine if a player’s ability will stick in MLB, but for many, it shows proof of concept. I was curious as to the differences among the players who survived the big leagues against those who didn’t, and if there were any noticeable trends in their batted ball or plate discipline data.

For the most part, there are similar increases & decreases between the two groups upon facing major league pitching, but those performing better in the big leagues actually strike out and whiff more than those who haven’t. The MLB wRC+ < 100 group sees a 9.4% increase in strikeout rate and a 4.7% increase in whiff rate upon promotion, while the MLB wRC+ > 100 group has a 3.2% increase in strikeout rate and a 2.5% increase in whiff rate.

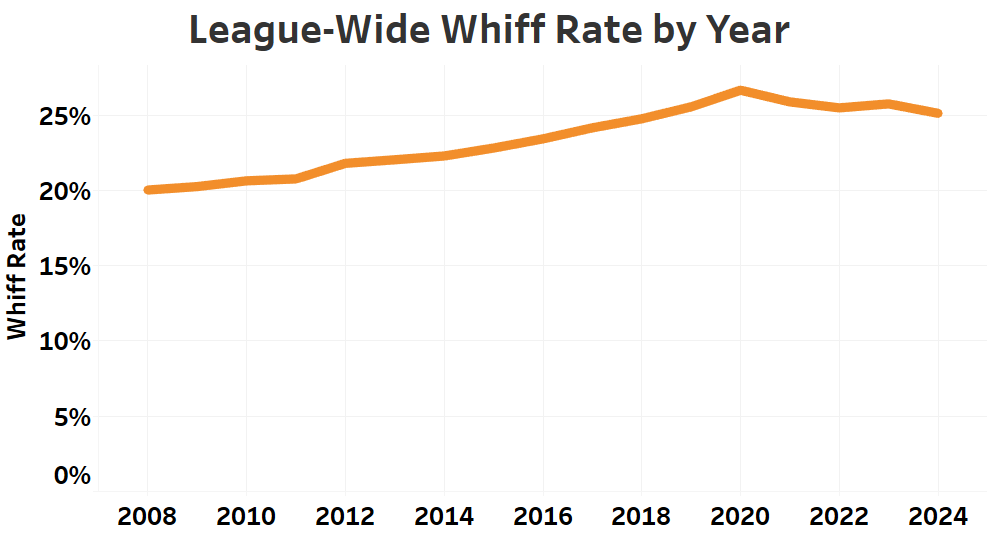

Some of these successful players could fall into the Westburg Paradox, a type of player who whiffs a lot but knows how to avoid strikeouts. MLB pitching has become so good that it’s hard not to whiff, so having some swing-and-miss in the profile could mean hitters aren’t swayed by whiffs.

On a similar note, it’s intriguing that the group of struggling players maintained their zone contact rates in the minors and big leagues, while the successful players saw a 2.9% increase in zone contact, putting them around the same 83% as the struggling players. The difference between the two subsets of players and the type of contact they’re making in the zone could be a stronger indicator for telling the two apart.

The players who did better hit more flyballs and pull the ball more, two key factors for success at the big league level. But like the plate discipline statistics, generally both groups of players lose a little bit upon jumping to the big leagues. The difference is how they mitigate their losses and find ways to hit major league pitching.

That brings us to two different players, Masyn Winn and Brett Baty, who exemplify both ends of this spectrum. Winn struggled in his first cup of coffee with the Cardinals in 2023 but has turned it around this year. Baty, meanwhile, has mashed AAA for two straight years now but can’t find his footing with the Mets.

Finding Success in the Bigs: Masyn Winn

Winn produced at a solid 108 wRC+ clip with 18 HRs and 17 SBs across 105 games in AAA last season and got the call in mid-August as the potential shortstop of the future in St. Louis. Not only did Winn underwhelm in 137 plate appearances, but his big league validity was questioned after he posted a 29 wRC+.

This year, Winn looks every bit the part. He has a 121 wRC+ in 236 plate appearances, boasting a .300 average along with 3 HR and 8 SB. While the defense has still been a work in progress, his 121 wRC+ is second among all National League shortstops, trailing Mookie Betts and ahead of his NL Central compatriots (Willy Adames, Elly de la Cruz, O’Neil Cruz, and Dansby Swanson).

Winn spent most of his minor league career slowly adding power but struggled to show any upon debut in 2023. What he’s done in 2024 is rely on the roots of what allowed him to tap into power later but have success now.

Winn has attacked 2024 by swinging more than he ever has. That’s meant both in the zone and out of the zone, but his strong hit tool is giving him enough line drives to fall for singles. This approach change brings Winn back to his early minor league days of high average/low power, but it’s required at the moment. In AAA, he saw just 45% of pitches in the zone. In MLB in 2023, he saw 57% of pitches in the zone, and couldn’t use his approach that worked when there were 12% less pitches in the zone.

He’s a great example of staying within his abilities while adapting, and that’s propelling him to success this season. Once he gets settled in and repeats success, don’t be surprised if we see him get to 20 HR power early in his career.

Not Yet Getting Over the Hump: Brett Baty

Brett Baty has been a better hitter than Winn at AAA but just can’t figure it out at the big league level. Baty got a short 42 plate appearance debut with the Mets in 2022, but his first real sample was last year. In 389 plate appearances, Baty had a 68 wRC+, 236th out of 245 players with at least 350 plate appearances. However, he hit at a torrid 146 wRC+ pace in AAA. This year, Baty got another opportunity to become the primary third baseman in Queens but struggled with an 88 wRC+ in 171 plate appearances before demotion. Although he’s only had 32 plate appearances in AAA, Baty is hitting .484 with 3 HR, suggesting that he’s still too good for the level.

Baty spent much of his time in the minor leagues working to lower his groundball rate but has yet to see those gains at the big league level. He’s held a 50% or greater groundball rate with the Mets in 2023 and 2024, despite working into the low 40% range in AA and AAA.

During his time with the Mets this year, he’s pulled the ball 47.3% of the time, a career-high for any level with more than 20 plate appearances. As Baty has tried to quickly adapt to his surroundings, the quality of his own output has quickly deteriorated. He’s continued to whiff at a high rate (26.2% is in the 42nd percentile) but actually improved his zone contact from last year. Baty has an above-average max exit velocity, but he’s yet to settle into the profile that works for him.

Concluding Thoughts

These two players are just two examples of how players can adapt to the harsh reality of big league pitching. Some changes work while others don’t, and at a young age, not many players have the runway to try and figure it out over time. Young hitters are often the most fickle player type, which means it often takes significant risk for them to find their footing in the big leagues. But if a player can accept the slight losses in plate discipline and batted ball quality, they can harness their ability to succeed rather than overcorrect.

I think the premise is interesting and worth exploring, but I’m not sure I see/understand the takeaway from this article. I recently asked Eno Sarris in an The Athletic chat: “Is there anything to be gleaned from the MLB performances of Jackson Merrill vs. Jackson Holliday? It’s probably all small sample size noise with respect to Holliday, but I feel like there could/should be some signal in there somewhere.”

It feels like there should be *some* reason/explanation for the lower-ranked Jackson Merrill’s successful transition to MLB and the higher-ranked Jackson Holliday’s massive struggles to adjust to MLB. Eno suggested that maybe it was a difference between “ceiling and floor,” as a more contact-oriented hitter like Merrill might adjust faster but not have the impact of a power-oriented hitter. Personally, given his strong exit-velocities and bat-to-ball skills, that answer felt like a bit of an undersell of Merrill’s impact potential/ability. However, he also theorized that maybe there were “swing path” issues with Holliday and, by inference, not with Merrill, but that such data was not yet publicly available.

So, I’m not sure what the answer is, but I feel like there is some signal to be found amidst all the noise.

Thoughtful comment. Thanks.