If you’re reading this, you’ve probably already consumed a lot of words and stats and takes and think-pieces about the Great Sticky Crackdown of 2021™, a.k.a. Goopgate, a.k.a. the Rob Manfred Theory Of Chaos. Spin is down, offense is up, pitchers are distressed, hitters are mouthing off, and as the name suggests, chaos reigns.

On an individual level, there’s more nuance to it. If Gerrit Cole didn’t look like Gerrit Cole on the Fourth of July against the Mets, he sure did when he fired 99 mph past Yordan Alvarez in the ninth inning against Houston five days later. Garrett Richards had to remake his entire arsenal, while Walker Buehler is 10-1 and seems to have remained unbothered.

The effect of the new rules is measurable on a large scale, but at the end of the day, Gerrit Cole is still Gerrit Cole. Still, some pitchers stand to lose more ground than others. Rather than looking at raw spin numbers or even line charts, I’ve taken to looking at movement plots to visualize how the changes are affecting each player differently. For example, here’s what Cole’s pitch movement looked like before and after his first substantial spin rate drop.

this is my new favorite way to visualize the spider tack rule. seeing changes to movement is more useful than raw spin numbers. Cole is still elite, obviously, but the difference is clear—less ride on the fastball, less cut on the slider, smaller differential between SL and KC pic.twitter.com/RtxdjOxyFv

— Zach (@pinetarkeyboard) July 14, 2021

Like the tweet says, the difference is clear—his fastballs have moved down and to the right on the chart, indicating less ride, and there’s also less cut on the slider and a smaller differential between it and the curveball. That’s a measurable difference, for sure. But ultimately, that fastball is still averaging 97.4 mph, and those breaking balls still have plenty of bite to them. Cole is okay.

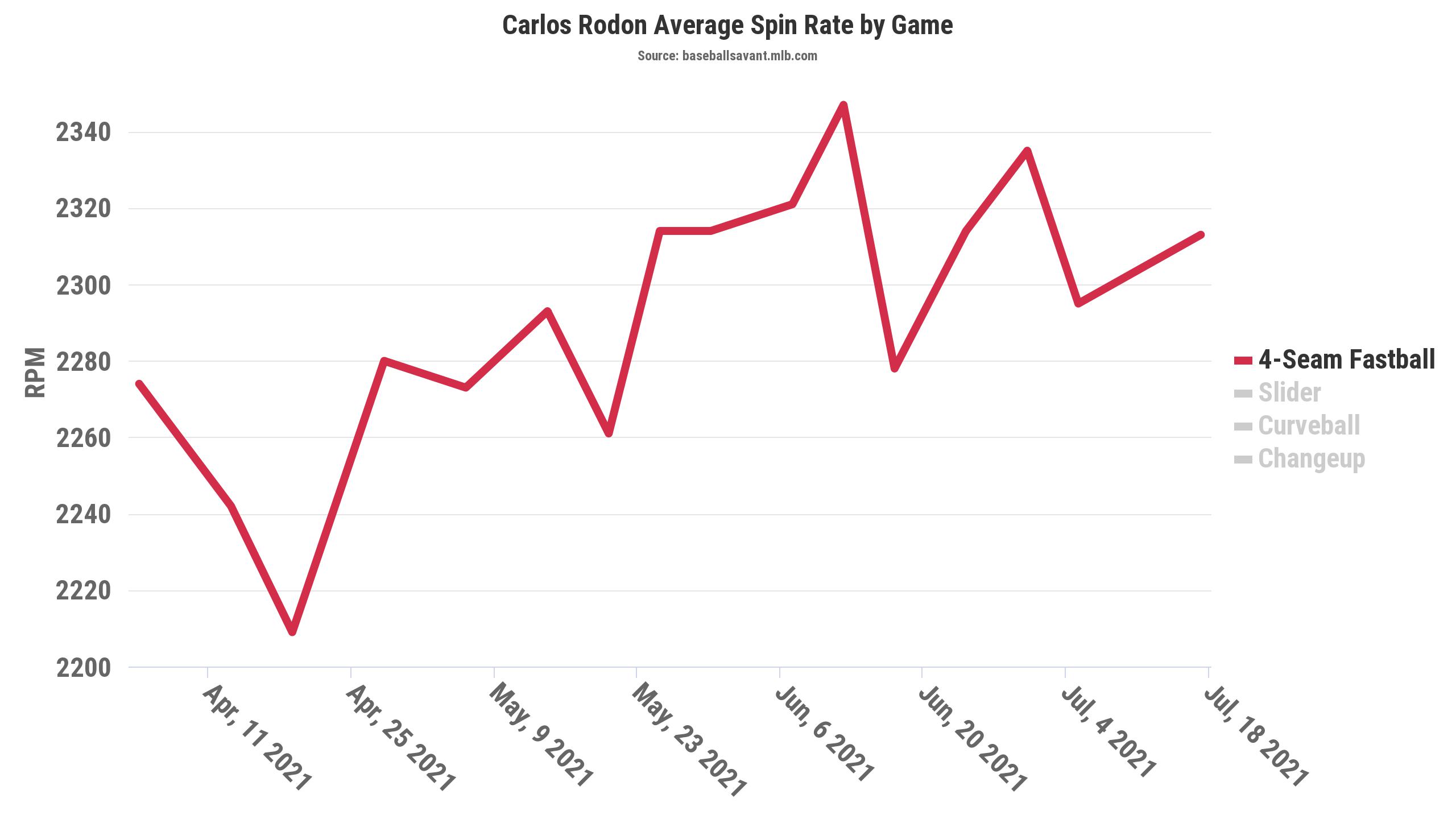

I do a fair amount of writing on the White Sox, and they provide a few other examples of how we can try to gauge the effect of the new rules on individual pitchers. Take Carlos Rodón, whose spin rates indicate that he’s been operating without any adhesives the entire time.

on the other hand, this is what it looks like when a pitcher was operating clean the whole time. the slight change in Rodón’s slider stems from throwing it a little harder as the season has gone on, but otherwise, he’s the exact same pitcher as he was before mid-June pic.twitter.com/I4EcSsV0OA

— Zach (@pinetarkeyboard) July 14, 2021

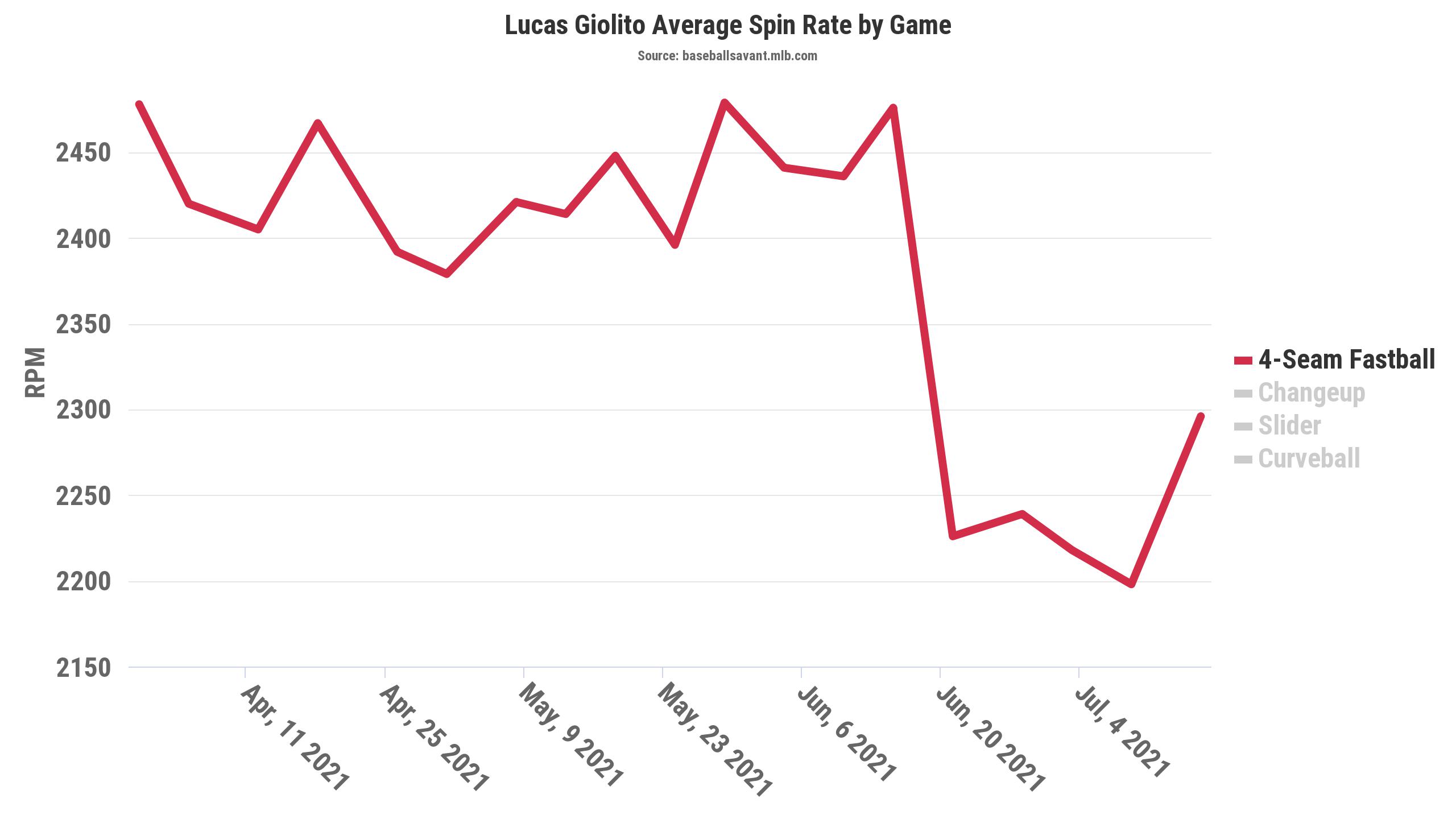

Rodón’s spin has actually increased as the season has gone on because his velocity has steadily increased, which also explains why his slider has lost a little bit of raw movement. Yet his fastball and changeup haven’t budged. He’s the same pitcher he was before June. The same can’t be said of Lucas Giolito, whose up-and-down performance since the crackdown has been a source of consternation for White Sox fans.

There’s no doubt that Giolito will have to find a way to compensate for the loss of ride on his fastball, His velocity is fine, but nothing special, and adhesives were the difference between above-average spin relative to his velo (25.9 Spin/Velocity Ratio) and a pretty below-average one (23.5 SVR). At the same time, his best pitch is relatively unaffected, as the goal of a changeup is to decrease spin, rather than had it. His slider doesn’t appear to have changed much either, possibly because it’s relatively gyro-heavy (31% active spin rate) and may derive some of its movement from seam-shifted wake. Giolito has adjustments to make, but the fundamentals are mostly still there. And believe it or not, I actually wrote that sentence before his complete game, one-run effort against the best offense in the league this past Saturday. Needless to say, I’m fairly confident in sticking with it.

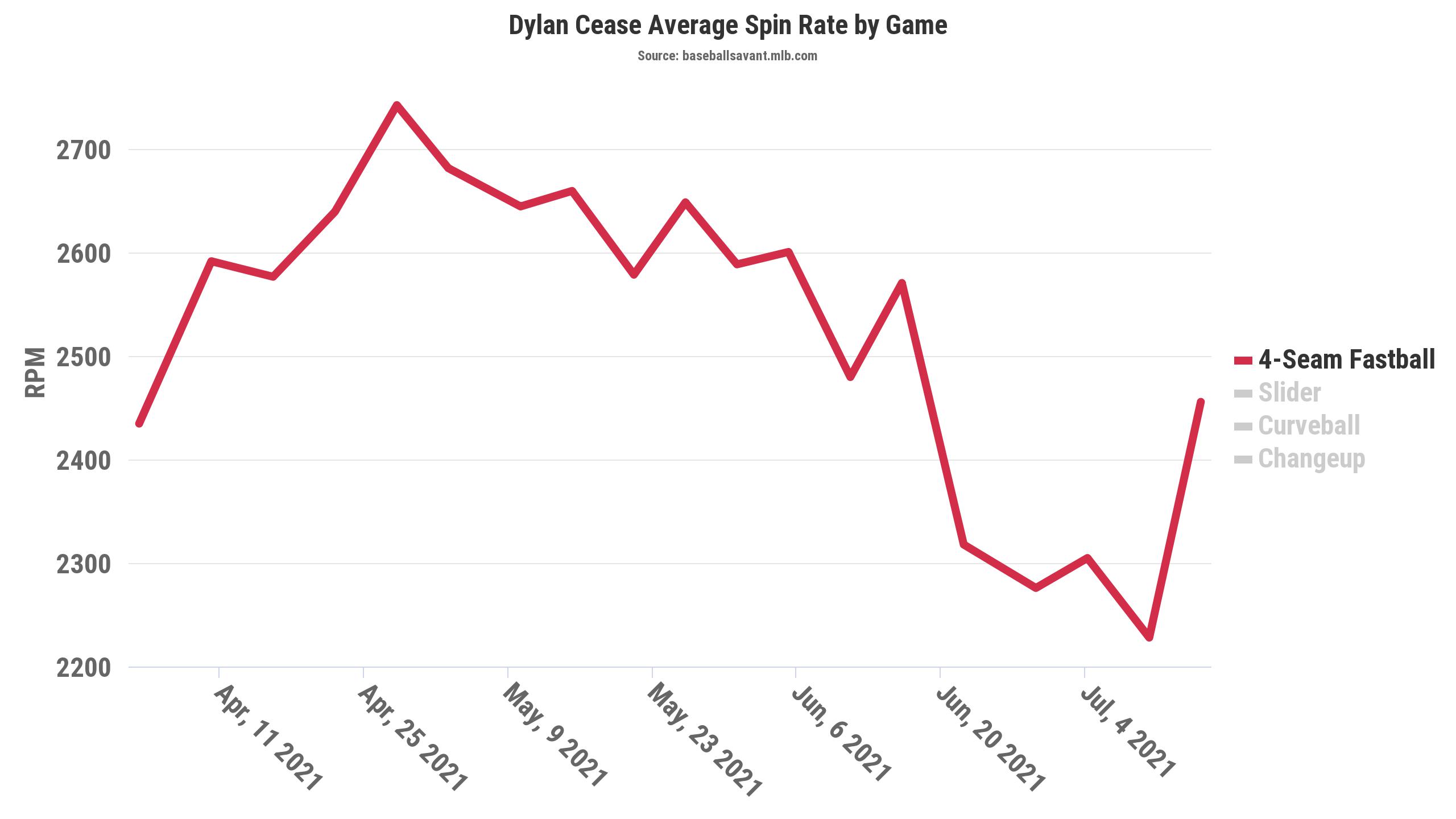

For our last White Sox example, the same can’t be said of Dylan Cease. whose before/after chart bears a fair resemblance to Cole’s.

In terms of raw spin, Cease has been one of the biggest losers of the crackdown, although I’m just as much of a loss as you probably are about his rejuvenated spin readings from this past Friday. Either way, his fastball lost a substantial amount of rise and his curveball, while still above-average, has been dropping considerably less. Like Cole, Cease certainly has the raw stuff to work around these changes. Whether he has the control to work within a smaller margin of error is a different story. For someone who’s already too prone to leaving hittable pitches right down the middle, there’s probably more reason to be concerned.

This was all a very roundabout way of reintroducing you to Yusei Kikuchi, who was recently selected to his first All-Star Game and is finally pitching like the front-line starter the Mariners hoped they’d be getting when they gave him $43 million guaranteed (with another $66 million in team options on the table) before the 2019 season.

Those numbers are already interesting, especially the disagreement between ERA estimators over whether he’s been better this year or last year — and that sentence was written while his ERA was still in the low-threes!

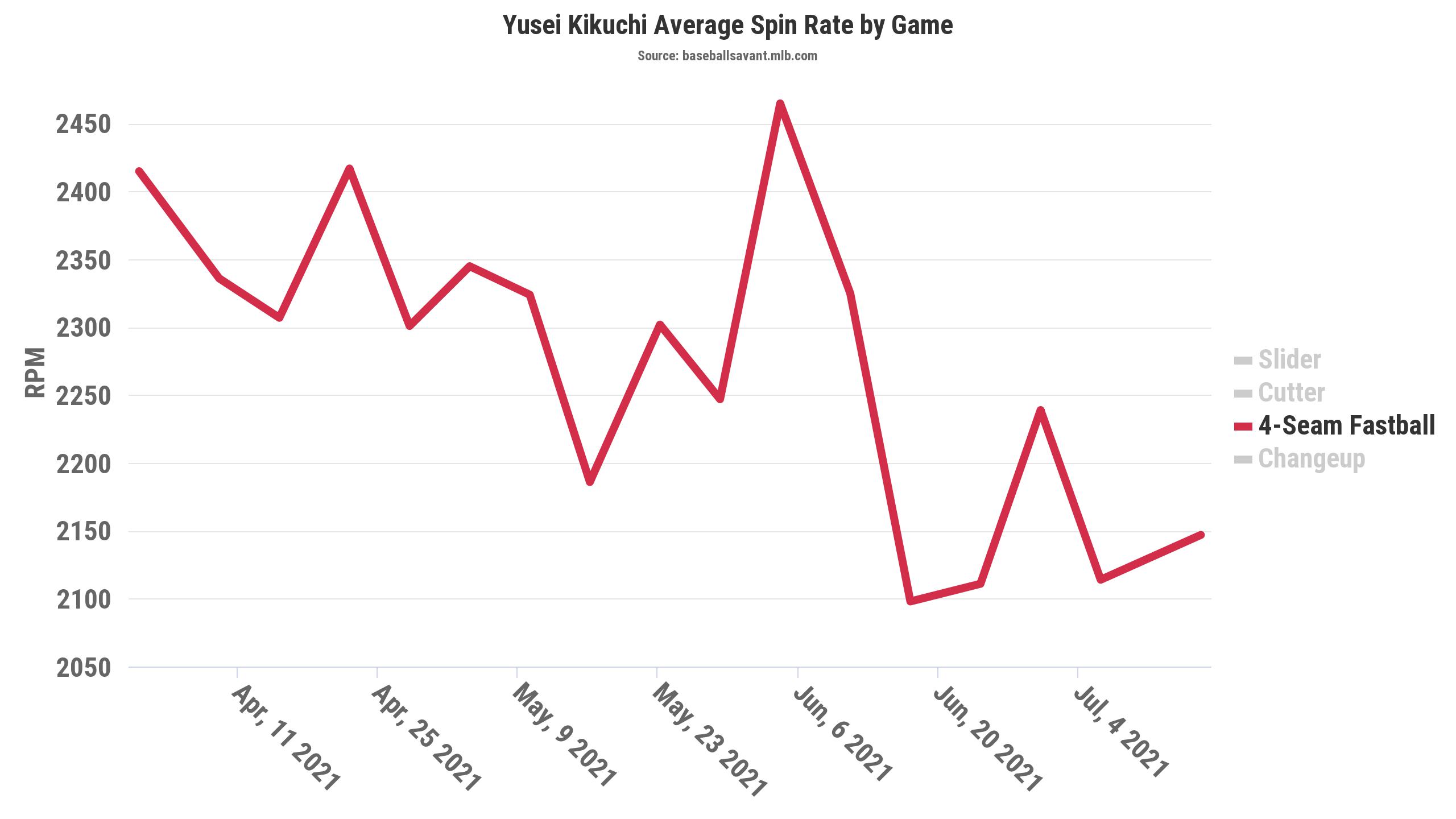

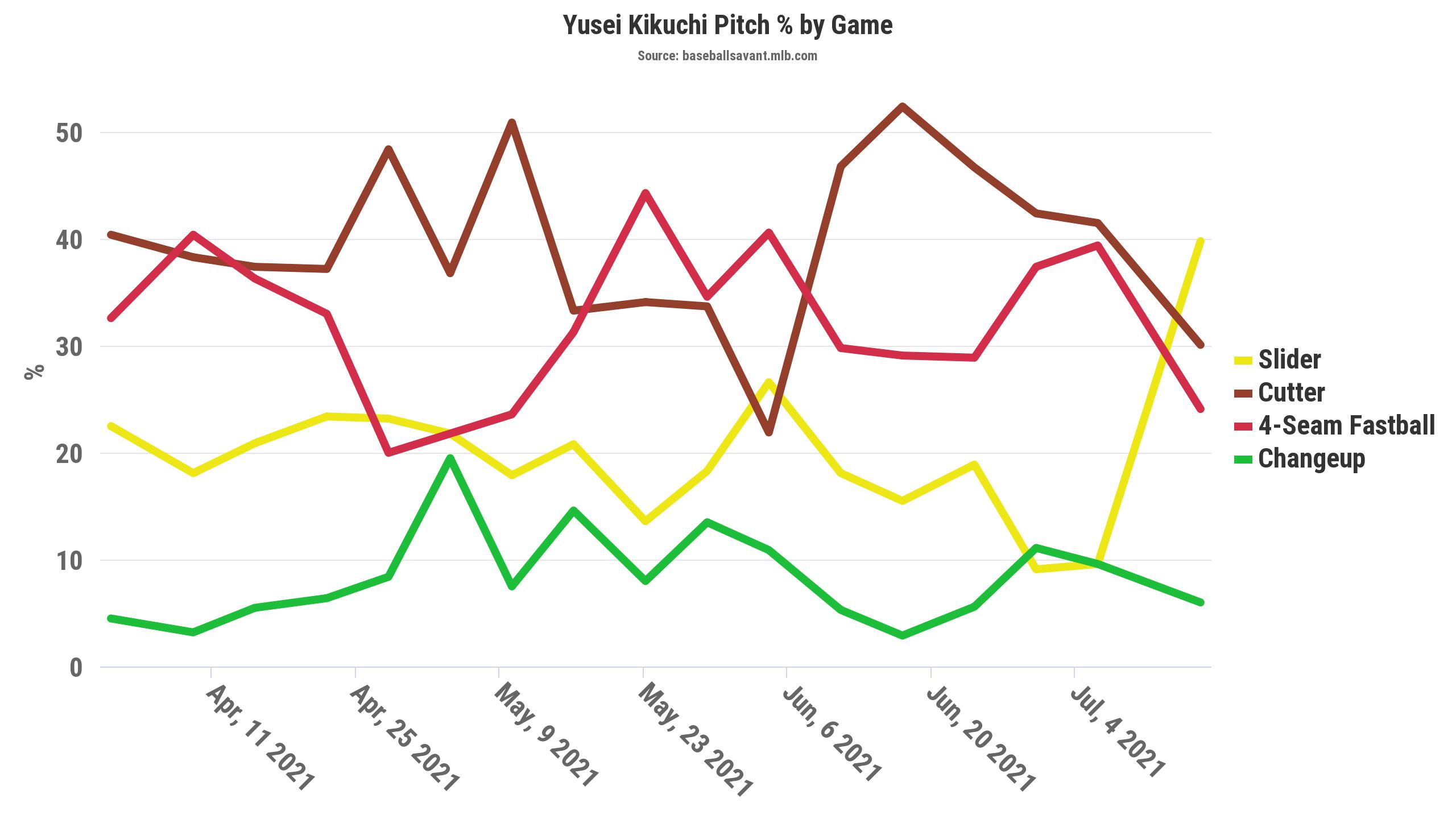

Anyway, up until last week, few pitchers had been more consistently solid so far this season. He recorded a quality start in 11 of his first 15 appearances on the year, one of the best marks in the league. With all that’s transpired in the last month and change, however, one has to ask whether MLB’s ham-handed rules implementation might have some adverse effects on Kikuchi’s second half. Unfortunately, the answer is that while we still don’t know what the final result will be, it’s clear that Kikuchi isn’t quite the same pitcher he was before the crackdown.

Ah, well, nevertheless. As with all the pitchers I’ve brought up so far, Kikuchi has had some ups and downs since the extremity checks began in earnest, though he appeared to have been mostly unbothered until his past two starts, a five-run thrashing at the hands of the Yankees just before the All-Star break and then a similar pounding from the Angels this past Saturday.

Even the best pitchers are allowed to have a bad game or two now and then, so similar to Cease, it’s fair to conclude from the bottom-line results that the reduced movement hasn’t changed Kikuchi’s trajectory all that much. But looking beyond individual game-level results paints a more muddied picture, and gives one the impression that he’s actually been walking a very thin tightrope since his first start with reduced spin on June 18th.

For a while, the bottom line looked even better after Kikuchi’s spin dropped, but even though he was inducing worse contact than he was early in the season, he had a whole lot of bounces go his way during those three starts, literally and figuratively. In spite of a high groundball rate, Kikuchi was probably getting quite lucky on balls in play, and his luck bottomed out badly over his past two starts. BABIP has plenty of flaws, but it should have been obvious that the pendulum was going to swing the other way sooner or later. Even more telling to me is his Left On Base percentage, the rate of baserunners a pitcher strands, which was well above league average and his career marks. For most of the season, he was stranding an absurdly high number of baserunners, especially for a pitcher who doesn’t strike hitters out at an exceptional rate, much of which can perhaps be attributed to getting more help from the Mariners defense than almost any pitcher in the league.

I’m not bringing this up to degrade Kikuchi’s first half. I’m happy that he’s finally succeeded, and it’s a credit to both the team and himself that he put himself in a position to maximize his stuff. And with stuff like his, sometimes you can make your own luck a little bit. He comes with more velocity from the left side than almost anyone in baseball; only Rodón and Shane McClanahan among all lefty starters throw harder than Kikuchi’s 95.5 mph heater. He certainly deserves some credit for making himself hard to hit.

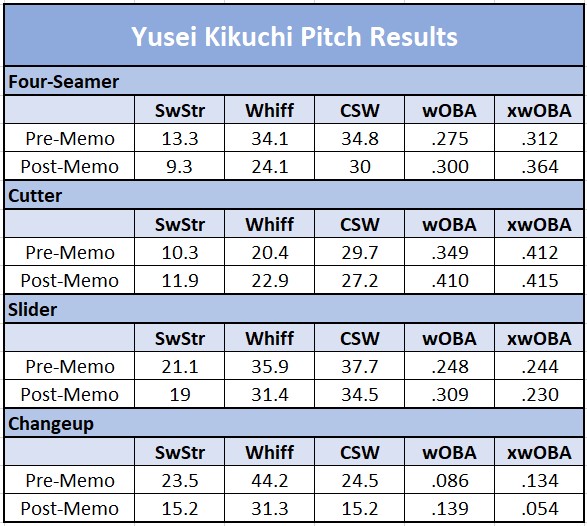

That being said, sometimes it’s good to make the adjustment before the horseshoe turns the other way. If the changes in Kikuchi’s pitch movement without tack are something to monitor, and the peripherals are a little worrisome, the pitch level results underneath his previously good run prevention over the past month raise clear red flags.

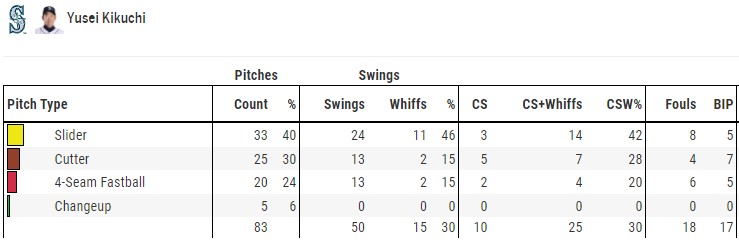

Ay ay ay. It feels kind of useless to highlight any one of those numbers individually, because they’re all quite a bit worse across the board. No matter how well it worked in the first half, throwing those first two pitches a combined 70% of the time—which is what he’s done for most of this season — just isn’t going to get it done going forward. It’s feasible that the extra movement lost thanks to GoopGate is the difference between the fastball and cutter tunneling well enough to induce whiffs and weak contact, and being left at the mercy of the batted ball luck gods. There’s also a fair chance that the aforementioned 70% fastball/cutter combo just wasn’t going to get it done forever. Our own Michael Ajeto wrote about Kikuchi over at Lookout Landing earlier this year, imploring him to consider using some of his secondaries more. It’s been more than two months since that piece was published, and, well, I’ll let Ajeto’s live-tweeting during Saturday’s loss to the Angels do the talking.

kikuchi has thrown 11 pitches, and five of those have been sliders ?

— Paul Sewald propagandist, and also Michael Ajeto (@dysthymikey) July 18, 2021

YUSEI IS THROWING 46% SLIDERS AND HAS THREE STRIKEOUTS ALREADY

— Paul Sewald propagandist, and also Michael Ajeto (@dysthymikey) July 18, 2021

*Seven Runs Later*

yusei kikuchi stop throwing your cutter challenge

— Paul Sewald propagandist, and also Michael Ajeto (@dysthymikey) July 18, 2021

There are two things in particular to unpack from these observations. First, there is some promise! Perhaps privy to the reduced effectiveness of those fastballs, Kikuchi went with his slider more than any other pitch against the Angels, throwing the pitch more than in any other appearance since September 2019.

The bottom-line results weren’t there against the Angels, but critically, the results on the slider were positive, drawing 11 swinging strikes and running a 42% CSW rate. The problem was that he was simply unable to get any positive results out of either fastball, drawing just four swinging strikes in total and failing to supplement them with enough called strikes to have any effectiveness.

Watching game tape makes it even clearer that the slider wasn’t the problem. Like it has for most of the year, it still made hitters look pretty silly, even with slightly reduced movement. Here we can see him expertly moving the pitch in and out of the zone to give Shohei Ohtani a White Castle Special, while also consistently hitting the back foot to get whiffs from right-handers.

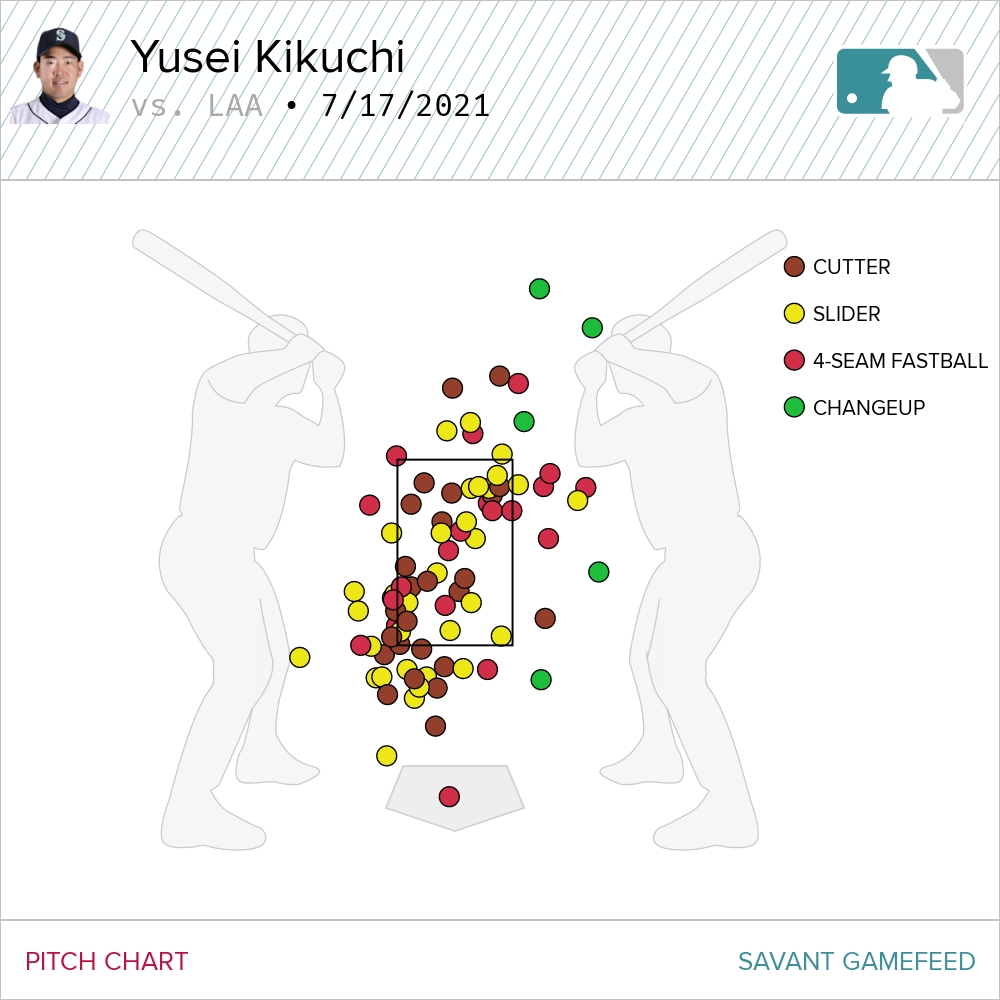

So again, leading with the slider wasn’t the cause of his woes on Saturday. The problem was that he simply had no command. Even though he managed to control the slider enough to get plenty of them into those low-corner sweet spots, he still left enough up and over the plate to get burned badly, not even to speak of his four-seam wildness.

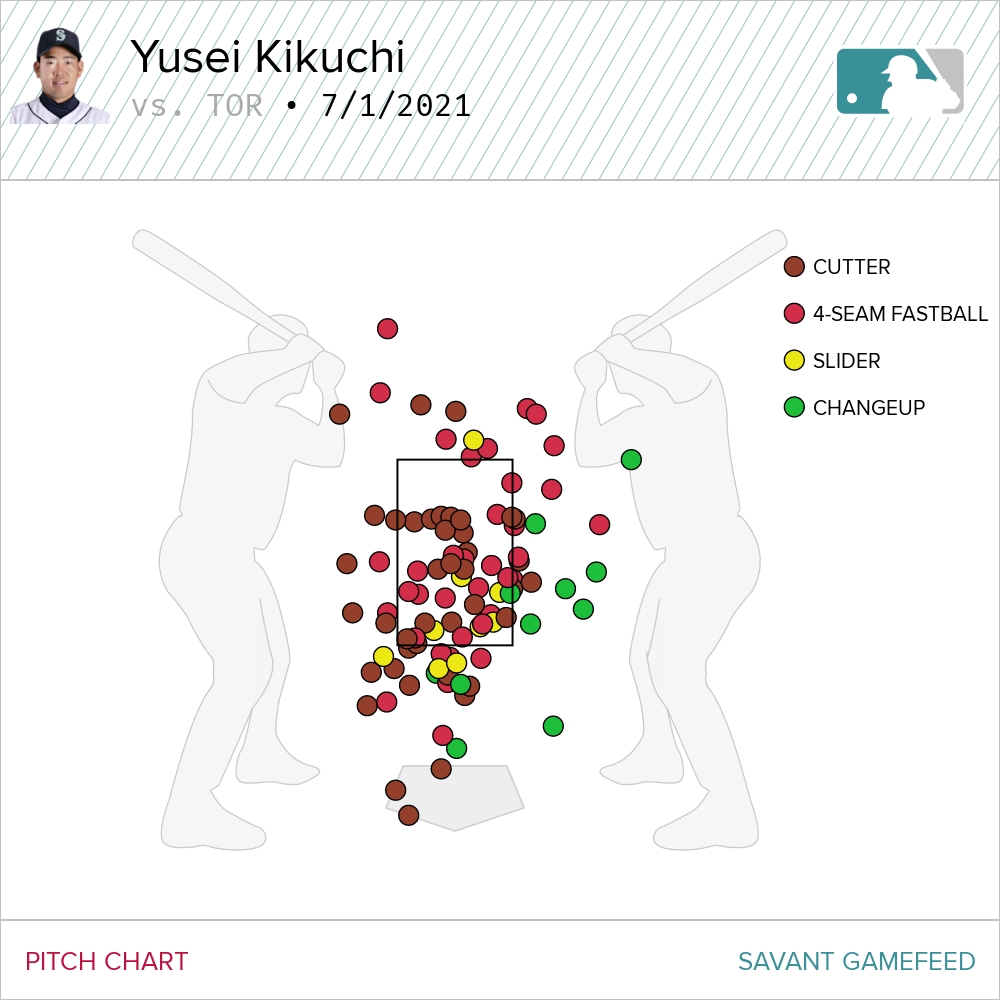

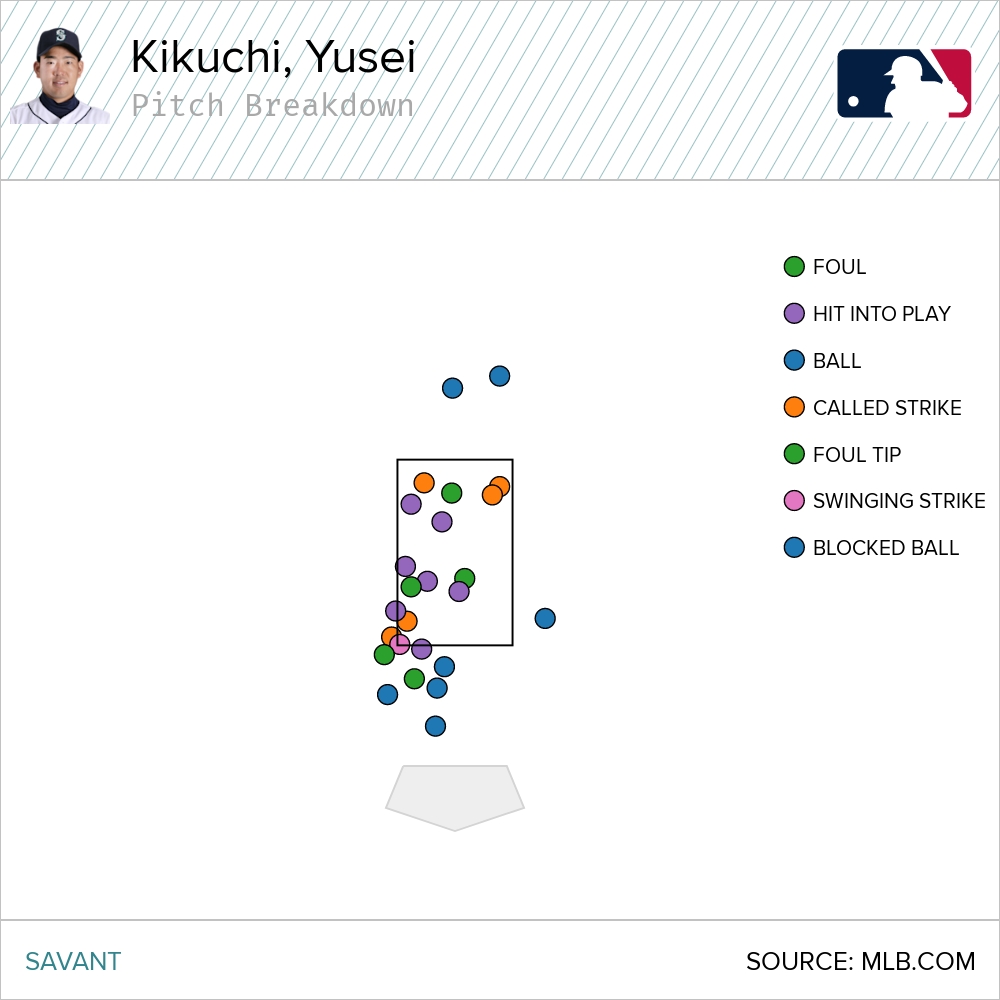

Now that is an ugly pitch chart. When a pitcher is consistently missing that badly with their four-seamer, they’re probably going to have a rough day. Compare that with how he attacked hitters on July 1st, when he held the high-powered Blue Jays offense to just a single run over seven innings.

As we’ve already established, having that level of success with almost entirely fastballs and cutters usually isn’t sustainable, but when you consistently fill up the strike zone like that, positive results are usually going to follow. Remember, Kikuchi is one of just a handful of left-handed starters who can reach back for 97 and 98 mph with some regularity. His fastball command doesn’t have to be great for it to be successful. But it has to be better than what we saw on Saturday.

Going back to Ajeto’s tweets, the second takeaway is that I also find myself strongly agreeing that more cutters aren’t the answer, either. Returning to the pitch-by-pitch table a little above, we can see that with the exception of grabbing a few more whiffs, there isn’t much of anything that the cutter does that his four-seamer doesn’t do a little bit better. Looking back at Saturday’s pitch chart, it strikes me that his location with the cutter wasn’t actually all that bad. This is more or less where you want to see a lefty throw their cutter, peppering the edges (especially to the glove side) and mostly avoiding the middle of the plate, save for a few misses that even the best pitchers make over the course of a full outing.

I didn’t watch every single one of those pitches and can’t speak to how frequently he was hitting his targets on the whole, but for the most part, those are executed pitches. Hitters were just straight-up not fooled by them, in the slightest. To begin with, the high number of foul tips is telling; even when hitters missed, they didn’t completely miss. More importantly, when they made contact, they made hard contact. Of those seven balls in play, five of them had exit velocities above 100 MPH, and only one checked in below the hard-hit threshold of 95 mph. These are not batters who are having trouble picking up on the ball!

Like I said, not fooled.

So, let’s recap what we found here. No matter how you shake it out, continuing to throw the four-seamer and cutter 70% of the time or more just wasn’t going to work out forever. That being said, it shouldn’t preclude Kikuchi from being an effective pitcher, because his slider is quite good, and his fastball, when spotted, can play as well as any heater in the game coming from a lefty starter. And even though this past Saturday’s results were poor, it’s clear that a better process is already being considered, if not in place. The slider can play as a primary pitch; it just remains to be seen whether he’ll keep trying it. His cutter doesn’t really do any of those things, and as we saw on Saturday, it’s simply not good enough to get it done on its own.

The first three months of the season weren’t a complete mirage; a well-tunneled fastball/cutter combo can still be highly effective by way of keeping hitters off-balance enough to avoid hard contact and big innings. But Kikuchi’s cutter isn’t 96 mph like Corbin Burnes‘, and it doesn’t have 5 inches of cut like Yu Darvish’s. The pitch gets hammered when it doesn’t have a good fastball to set it up, so moving forward, it seems clear that if he’s going to keep up his current usage, he needs to start spotting that four-seamer a lot better than he has been recently.

Maybe that’s the problem. Maybe a lack of fastball command is what prompted the development of the cutter in the first place. He probably has some very good reasons for liking the pitch much more than the numbers say he should. But as long as he continues to rely on the cutter as his primary fastball, he’s probably going to have a ceiling on his game that’s lower than the All-Star first half he just posted. Even if he does have games where he’s spotting the four-seamer well, there’s just not much evidence that the cutter is effective enough to justify even a 30-35% usage.

So with that, I’ll conclude by begging that Kikuchi simply start trusting his four-seamer a little more. I don’t usually like to be prescriptive with my articles, because I very rarely have the confidence to suggest that I might know an MLB pitcher’s arsenal better than they do. This one is a little different. The time for Yusei Kikuchi’s big adjustment is now. In fact, it already looks like it’s underway — whether he can stick with it might determine whether his second half is as successful as his first.

(Photo by Leslie Plaza Johnson/Icon Sportswire)

Really nice article, Zach!