(Photo by Mark Goldman/Icon Sportswire)

With the rise of the shift in baseball, many hitters are struggling to adjust against defensive formations. Thanks to Statcast, we can quantify who is facing the shift the most and how much it’s affecting them. The types of shifts recorded are ‘infield shift’ and ’strategic shift’ – infield shift being a standard shift you’d see against left handed batters and strategic shift representing any other type of shift. For the purposes of this analysis, we will be looking at horizontal angle in relation to results on a standard infield shift.

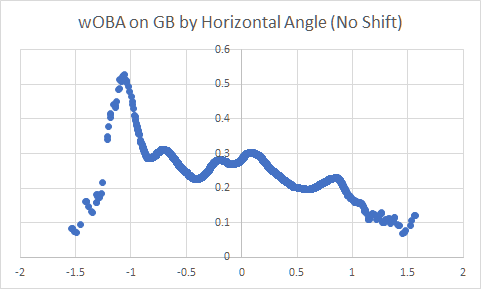

Statcast doesn’t explicitly track horizontal launch angle, but batted balls are plotted as pixels on an image of a baseball field. The angle can be estimated by comparing the coordinate of home plate to the location of a hit. The following graph shows the relationship between horizontal angle in radians to wOBA on groundballs with standard fielding position in 2018 so far.

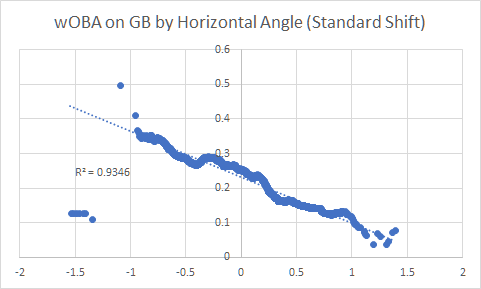

The first spike in the graph around -1 radians corresponds roughly to groundballs hit down the line at third base. To the left of that would be a soft hit that likely managed to stay fair without leaving the infield. Positive results on horizontal angles are correlated with holes between defenders, but small variations can lead to likely outs. The data set is difficult to model accurately because of this. However, the plot is much more linear against the shift.

A simple linear regression fits the model very well with an r2 of 0.9346. It is intuitive that hitters should have better results as they can hit farther away from the shift. xwOBA struggles the most with groundballs, but horizontal angle alone against the shift correlates strongly with results. It has already been established that hitters have some control over which parts of the field they tend to hit towards, so horizontal angle may find a use in predictive value against the shift.

The following table shows the qualified players with the lowest expected wOBA based on horizontal angle (hxwOBA) that faced a standard shift on at least 50% of their groundballs. All have a significantly lower wOBA on groundballs than xwOBA with the exception of Cody Bellinger. These hitters can be expected to see worse results on groundballs than average and as a result tend to have lower BABIPs as well.

| Player | Shift Rate on Groundballs | hxwOBA vs the Shift on Groundballs | wOBA on Groundballs | xwOBA on Groundballs | Overall BABIP |

| Joey Gallo | 89.3% | 0.165 | 0.176 | 0.287 | 0.220 |

| Justin Smoak | 59.8% | 0.167 | 0.188 | 0.250 | 0.294 |

| Bryce Harper | 54.0% | 0.168 | 0.157 | 0.230 | 0.230 |

| Logan Morrison | 68.9% | 0.173 | 0.105 | 0.232 | 0.212 |

| Anthony Rizzo | 59.0% | 0.175 | 0.193 | 0.257 | 0.270 |

| Cody Bellinger | 57.4% | 0.175 | 0.241 | 0.209 | 0.289 |

| Matt Carpenter | 84.2% | 0.175 | 0.117 | 0.278 | 0.308 |

| Kyle Seager | 69.7% | 0.176 | 0.180 | 0.263 | 0.266 |

| Alex Gordon | 58.5% | 0.179 | 0.171 | 0.234 | 0.292 |

| Michael Conforto | 50.6% | 0.181 | 0.199 | 0.205 | 0.275 |

Do you know why Bellinger is an outlier? I do… its because he beats the shift pretty regularly. He flips stuff the other way or actually pound balls into the ground the other way. It looks really hard to do, but he does it a lot. Thats one of the reasons I don’t like Bellinger as a fantasy asset – if you take away the slappy little hits I think he hits under .200 and might not even have a steady job. The silver lining is that I think he could be a high average hitter if he ever wants to ditch his grotesque uppercut. The reason he stinks is that he has two swings – neither particularly great but its hard enough to maintain one. Thats how he beats the shift – sometimes he does a reasonable impression of Joey Votto with two strikes.

I am not sure that dead pull guys wouldn’t suffer without an exaggerated shift. You don’t need a shift to make a guy with a bad approach look bad. If you can’t make an adjustment when the defense is waiving around a red flag, then you probably have some serious problems as a hitter – hard times should be expected for these type of hitters as hitting GB through the pull side isn’t really skill – you are talking two or three feet either side of the 2B (in most cases). I don’t think the shift takes much away – more than anything it adds insult to injury.

There are some huge flaws with expected outcomes. I think that is mostly what you are illuminating here. Expected outcomes love hard hit balls, but if you are hitting them right at the strong side of the infield – you can’t hit them hard enough for it to matter – that horizontal angle is just as important as vertical for hitters. Much like some hitters have crap LA, some hitters are trash at using the whole field. You can shift against this type, but they get themselves out just fine as is. The funny thing about angles is that LA gets all the talk, but players can’t directly control it – they can try but you don’t get to choose the angle that a round ball comes off a round bat. They can try to hit GB of FB, but they don’t get much of a say in the actual generated angle. Horizontal angle on the other hand, is something that players have a lot of control over – its one of the most important skills a player can have. Some players just forfeit that skill and they pay for it. I am not sure the shift has a lot to do with it. I have never seen data to show that the shift is effective as a whole. I don’t doubt that an overshift would help a bit for dead-pull guys, but not as much as people think. Players that don’t pay the horizontal angle game just give away a ton of outs, which ironically in the context of Statcast have tasty EVs, which is the bulk of the value.

You mention the rise of the shift. Its not rising is it? I think peak shift came and went. I am seeing more teams employing a man up the middle as opposed to the moronic idea of two guys on one side of the infield approach (one in the grass is just as dumb) – to me, that is the decline of the shift… the over-shift at least as baseball has always employed shifts – which seems like what we are rotating back towards.

There is a moderate inverse correlation between how often a player is shifted and their BABIP, but like you said that doesn’t necessarily prove the shift is actively causing these players to perform worse on batted balls. It’s possible that hitters who face the shift most often are the ones that don’t perform well on groundballs anyway.

I think what does provide more evidence of what defensive advantage is gained from the shift can be seen in the charts I posted in this article. Teams effectively trade the smaller gaps between defenders (where results in groundballs have an uptick in results) for a formation that punishes contact the farther towards the right side that the ball is hit. So hitters that would at least occasionally hit some groundballs through gaps in the right side have that possibility greatly diminished. With how well horizontal angle correlates with results against the shift by itself, teams can effectively take away the advantage gained by hard contact and challenge hitters to change their approach.

To answer your last question, Statcast recorded a shift on 17.5% of plays this year, up from 12.1% in 2017 which is what I was looking at in the context of that sentence.