For me, there’s something compelling about watching big left-handers pitch. Partly, perhaps, because it represents one of the beautiful things about baseball. While there’s certainly a normative body type, baseball is about aesthetics more than maybe any other sport, and it’s wonderful to watch how many ways there are to skin a cat, so to speak. Baseball still has tons of issues with being a punishing space for people who don’t fit that norm, but it’s also a fact that there’s no other sport where CC Sabathia and Marcus Stroman, Randy Johnson and Bartolo Colon can all play the same position.

This was on my mind while watching Ryan Weathers pitch last week, because like I said, there’s something compelling to me about heavyset left-handers baffling hitters. Sabathia, David Wells, or late-career Jon Lester represent the aesthetic I love in pitching, maybe because they’re so diametrically opposed to me, a right-hander on the smaller side of things. Weathers certainly fits the bill, but of course, there’s much more interesting things to him than that. Fernando Tatís Jr. is usually the Dad most subject to age-related praise, stats, and fun facts, but even at the tender age of 22, he’s not even the youngest player on the team anymore. That honor belongs to Weathers, who with a 2020 postseason cameo became the first high schooler from the 2018 draft to reach the majors, and, last Thursday, held that mighty Dodgers lineup to just a single hit over five and two thirds innings.

I say all this because, for better or worse, his “husky” frame was made into one of his defining features as a first-round draft prospect out of a Tennessee high school. Given the nature of the MLB draft, there’s nothing teams love more than projectability, and physically, Weathers didn’t seem to have any of that, in spite of supposedly great athleticism. Yet, there he was last Thursday, dicing up the Dodgers on national TV at age 21. And he did it with that big, mean, left-hander aesthetic that we haven’t seen enough of since C.C.. The boys over at Cespedes BBQ summed it up better than I can.

THATS WHO HE REMINDS ME OF. Just different hair. pic.twitter.com/sMGYCXMbuy

— Céspedes Family BBQ (@CespedesBBQ) April 23, 2021

Weathers has now allowed just a single earned run over his first 15 and a third innings of regular season action, with an impressive 16/5 K/BB rate to boot. It’s nigh-impossible to have a 0.59 ERA that ERA estimators actually think is earned, so naturally, they’re a bit less optimistic. It’s still great to see that there’s agreement more or less across the board that Weathers has in fact been pretty dang good, if not quite 0.59 ERA good.

| ERA | FIP | xFIP | SIERA | xERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.59 | 3.03 | 3.67 | 3.39 | 3.71 |

That kind of consistency across metrics is actually moderately rare, and while the microscopic sample size makes it misleading — that chart might look a lot different next week! — it’s also a little reflective of the same skills that made him such a precocious, fast-moving prospect. None of his skills are exceptional. As we’ll see in a moment, there’s nothing particularly special about any of his stuff. But he does just about everything well.

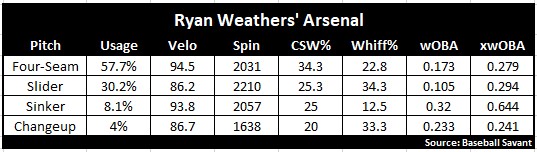

That he has advanced command should almost go without saying; the 94.5 mph he’s averaging on his four-seamer is nice, especially from the left side, it’s not so electric as to carry a 20-year old pitcher to the majors by itself. Same goes for the slider. But when you can command 94-95 like he can, even without any other super compelling attributes like high spin or crazy tilt, you can parlay even a limited arsenal into a K/BB rate nice enough to get FIP to like you, suppress homers enough to get xFIP to like you a little less, and enough grounders and weak contact to get SIERA and xERA to take you seriously.

All of those numbers are likely to change in the coming weeks, but the point stands. There’s something here. What is that something? It’s pretty simple. Weathers has been almost entirely fastball-slider in the majors, and even though he’s not a traditional fastball-slider power pitcher, there’s something about this mix that’s working for him. This is pure conjecture, but it’s probably not the handful of sinkers and changeups he’s mixed in with the other two.

What does that fastball-slider combo look like in action? Again, with numbers like that, you’d probably expect something pretty nasty. But you might be surprised. Getting a little help off the edge of the plate from the umpire against Sheldon Neuse before tying him up with a well-placed slider is a pretty good representation of how Weathers operates.

And, because I spent way too much time re-learning how to do these on the fly, I’m going to make you watch a rough overlay of how those pitches work together.

I’m no Alex Fast, Sunday Night Baseball Graphic Artist Extraordinaire, but again, there’s nothing terribly exciting about that on the surface. If it wasn’t clear before, it should be now that this isn’t your traditional slice-and-dice fastball-slider operation. Weathers isn’t going up there saying “here’s my stuff, take your chances.” If 98 mph is the new 95, then Weathers sitting 92-93 out of the rotation is the new finesse lefty. “Pedigree” is, for the most part, an entirely made up and problematic scouting attribute, but there’s no doubt that Weathers pitches with the feel of someone who’s been on an MLB field their whole life.

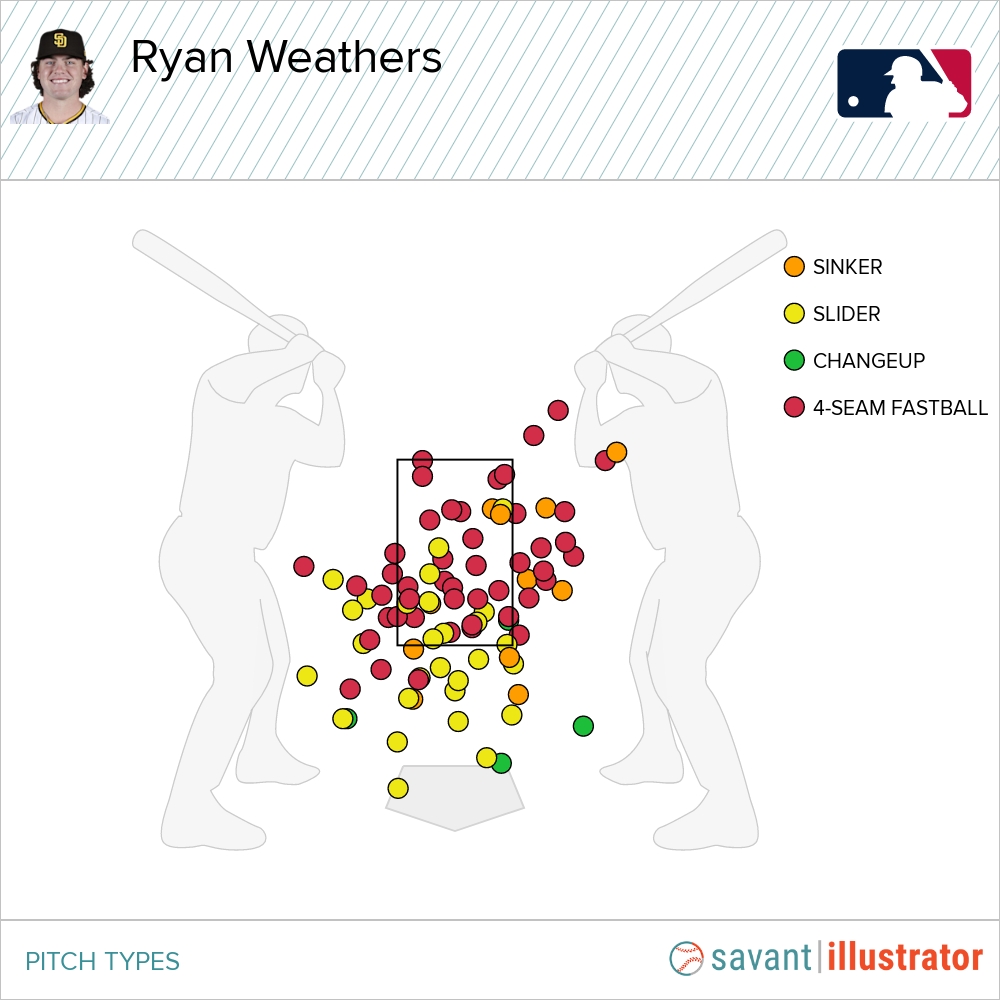

The look of annoyance Neuse gives after not getting that second call wasn’t an isolated case, either. That sequence is a pretty good representation of how Weathers attacked the Dodgers’ lineup all evening:

Look at all those low four-seamers and slightly lower sliders! It would fit right in on the 2012 Pirates, but it seems a bit anachronistic now. The aforementioned Alex Fast had a fantastic article drop a few months ago about how to be successful with low four-seamers, but Weathers lacks the elite velocity and outlier VAA to make it fit the bill he was looking at. Yet he still managed an elite 41% CSW on the pitch against the Dodgers, and it currently sits at 34% on the year, well above the league average of 29%.

How does he do it? As Jay Jaffe pointed out in his writeup of Weathers late last week, the magic was in called strikes: He got 20 of them in his start against Los Angeles, masterfully peppering the edges of the plate to get calls on pitches the Dodgers just weren’t going to swing at.

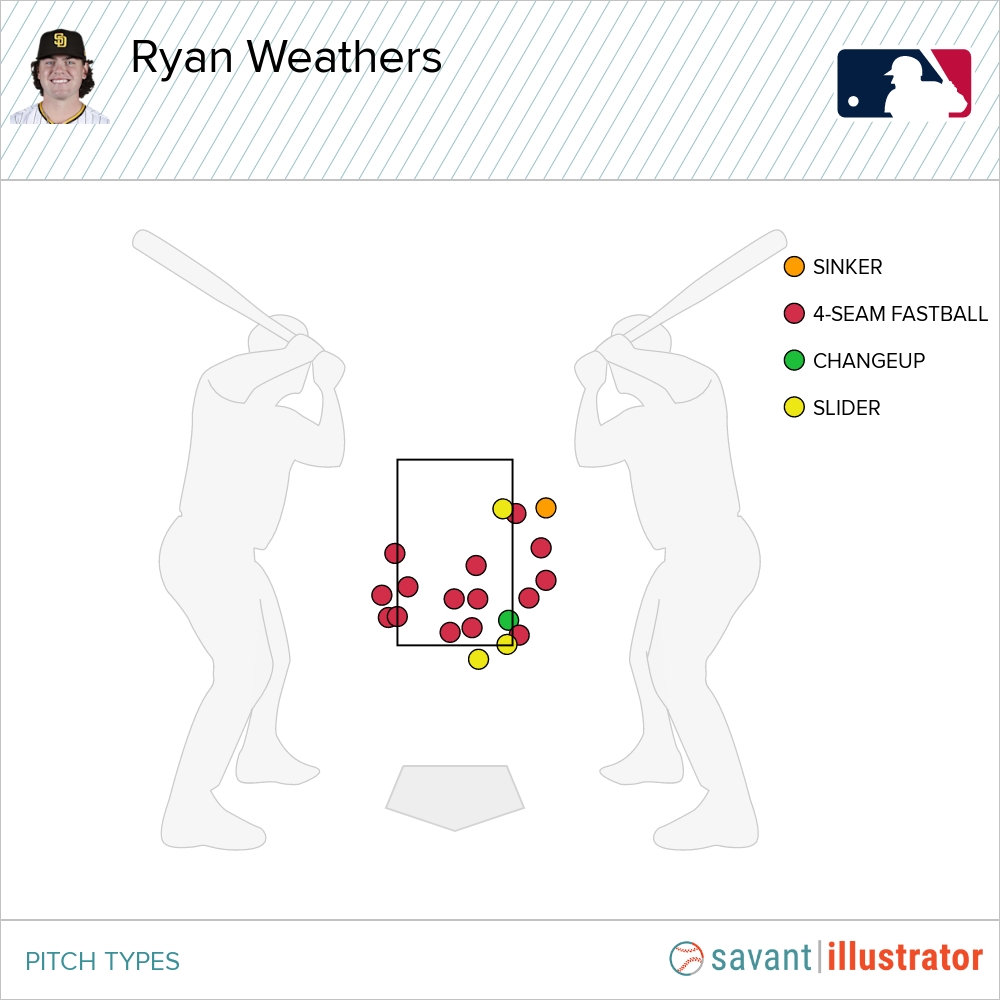

That wasn’t just a fluke, either. Through the first month of the season, a full 25% of Weathers’ four-seamers have landed for called strikes, ranking twentieth out of the 242 pitchers with at least 50 fastballs thrown on the year. As Jaffe also pointed out, those called strikes on the edges come in some part thanks to the excellent run he gets on the pitch. More than 11 inches on average, to be exact. As far as movement goes, it’s pretty much the only thing about Weathers’ arsenal that’s technically “above average,” and it’s mostly thanks to the fact that in spite of his low spin, he gets about as much out of that spin as is humanly possible, with a 99% spin efficiency that sits at the very top of the leaderboard.

When you combine that amount of run with 60-grade command, you can do things like throw a fastball that catches all of the plate and freezes Mookie Betts (!!!) so badly that he jumps out of the way and instantly walks, unquestioningly, back to the dugout.

And when you do that consistently enough, you earn the benefit of the Maddux strike zone, as he did here with a beautifully executed backdoor four-seamer, which isn’t often a thing but certainly was to Luke Raley here.

Nice! Very nice! As long as he continues to live in the 93 mph range and reach back for 96 when needed, that’s a fastball that will be much better at avoiding hard contact than most others that don’t have a top-of-the-zone profile.

At the same time, he’s still only shown two pitches in the Majors. And if you’re going to be a two-pitch starter in the Majors, both of those pitches better be pretty damn good. Now that we know why his fastball probably plays up a little bit, we can find out what the deal is with the slider. In terms of what traditionally makes a slider good, it doesn’t measure up very well. Its 25% CSW is one of the worst marks in the league, ranking 135th out of 149 qualifiers, and its whiff and swinging strike rates don’t measure up much better.

Ultimately, though, he has yet to allow a hit on the slider, one of two players out of 114 who have 10+ batted balls on the pitch who’s still kept opponents completely off the board (The other? Mike Mayers. Go figure). The below-average .294 xwOBA allowed on the pitch suggests that it’s more or less pure luck that’s held the hit total at zero. I watched every slider that hitters have put in play against him this year, and looking at a couple of those defensive plays, it’s hard to argue that there’s not quite a bit of luck involved.

That’s not being super fair, though. Most of those batted balls aren’t exactly smoked, and even the harder hit balls don’t look like the hitter is making ideal contact. It’s also instructive on how Statcast metrics can be a little misleading. For example, by expected batting average, Sheldon Neuse’s deep flyout to center has about a 64% hit probability, whereas the grounder that needed some Manny Machado acrobatics to rescue had just a 57% hit probability. On the other hand, Neuse’s fly ball is probably an out in just about every stadium in the majors, while Turner’s sharp grounder is probably a hit against the 27 or so third basemen who aren’t Machado, Arenado, or Chapman.

This isn’t really a criticism of expected stats, just an example of where one has to use a little nuance and research gumption when evaluating a pitch and player. If one was super focused on reading too much into the small handful of batted balls he’s allowed so far, one would probably miss the weirdness that makes it an interesting pitch!

Let’s get to the point — what, exactly, is that weirdness? Again, the samples here are really small, but things get interesting when you split Weathers’ slider between those thrown in the zone and those thrown out of the zone:

| Location | Pitch % | Swing% | SwStr% |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Zone | 36% | 77.8% | 25.9% |

| Out of Zone | 64% | 29.2% | 10.4% |

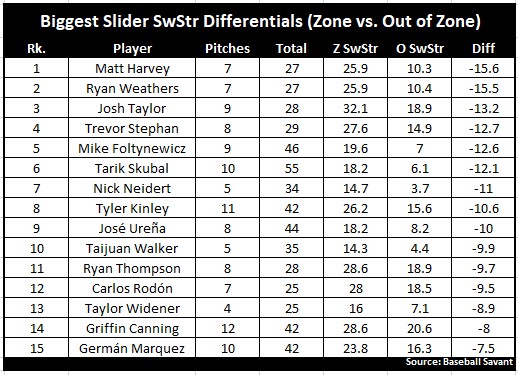

While a slider getting more whiffs in-zone than out-of-zone isn’t super unusual, especially with these sample sizes, but it’s probably worth nothing that Weathers has the second biggest negative differential in all baseball between the two:

Huh. Interesting list. As my co-host Ben Palmer would say, who’s to say what’s good or bad? There are some very good sliders on that list, and some very washed sliders on that list. Either way, it doesn’t make Weathers’ any less interesting.

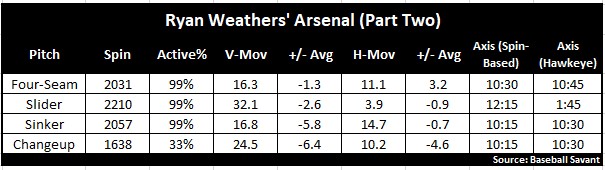

So what’s really going on here? The answer might lie with a term you may or may not have heard being thrown around quite a bit lately: seam-shifted wake. If you’re not familiar with the concept, I’d definitely encourage you to do some googling around but the idea is pretty simple. Because the seams on a baseball are irregular, the air flow around it while it’s in the air is going to be uneven—but only if the seams are oriented in a way that makes them irregular. For example, when you throw a four-seam fastball, the ball is gripped and released in a way that makes the seams spin in a mostly regular pattern. But if you spin something with a two-seam grip, the pattern of the seams over the “front” of the ball is irregular. As a result, the irregular air flow around the ball gives it a kind of movement that isn’t explainable by spin alone.

It’s kind of a mind-bender, so don’t worry if that doesn’t make perfect sense. All you need to know is that some pitches are thrown in a way that gives them extra movement that isn’t really captured in the way that we calculate the movement numbers you see in the chart with Weathers’ pitch specs. Because of the fact that the two-seam grip is the most intuitive, visible demonstration of seam-shifted wake, it’s usually sinkers and sinker-ballers that get the brunt of the attention when it’s talked about. But as it turns out, Weathers’ slider generates a healthy amount of seam-shifted wake, which might explain why it’s been more successful than one might anticipate.

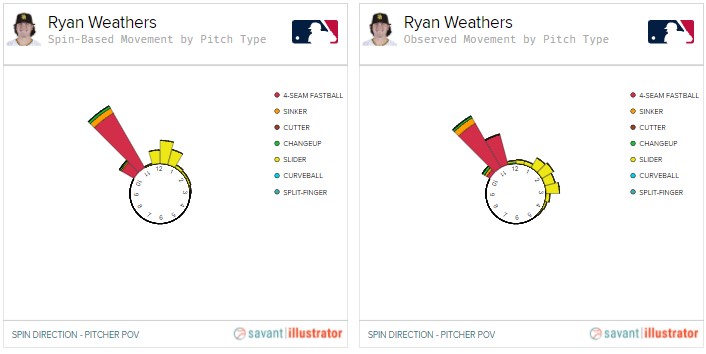

How do we detect the presence of seam-shifted wake? It’s only been made possible recently, with an upgrade to Statcast camera technology that lets us see the difference between what a pitch’s spin direction (also called spin axis, a.k.a., the degree that the ball’s spin is tilted left or right, like how the earth spins on a slanted axis) should be based on its movement, and what it actually looks like according to these ultrapowerful cameras. If you’ve been paying attention, you probably noticed it on that chart up there, but this is a better visualization.

Because having inefficient spin is quite literally how sliders work, it’s usually almost impossible to pin down a single, concrete spin direction for any individual pitch. But we don’t need to get super minute to see the differences in how Weathers’ slider should work by the numbers and how it actually operates. You’ll notice that with his across-the-board excellent spin efficiency, none of Weathers’ other pitches show signs of any kind of physics phenomenon, even the sinker (though, again, sample size). There’s just something about the way he grips the slider that makes it move differently than the spin would otherwise dictate.

This doesn’t mean that the slider is going to be good long term, or that this is why it’s good now. But it might explain it! We still don’t have a very good grasp on the effects of seam-shifted wake yet, but we do know that the movement properties of pitches with a lot of it tend to be much harder to capture. Looking again at the way he Weathers’ uses his fastball slider combo, the eye test tracks with the idea that the slider isn’t quite as simple as it looks. As a lefty without ultra-premium velocity, Weathers’ game is predicated on making hitters uncomfortable without excessive power, and as the results indicate, he’s been really successful so far. With good command, a SSW-aided slider that tunnels well with a running fastball is going to be an effective combo, even if neither are special on their own.

Who knows if any of this means Weathers will continue to run it up over the course of this season. Even with all that stuff going on, hitters will adjust, and it’s fair to ask whether he’ll be haunted by lack of a third pitch when it happens. Though he’s used it sparingly, Weathers does have a changeup, though it was mentioned relatively little in prospect reports. Between Chris Paddack and Dinelson Lamet, the Padres haven’t been shy about eschewing conventional wisdom and letting their two-pitch pitchers ride their two pitches out of the rotation. It remains to be seen if Weathers can hold his command and velocity consistently enough to make it work. But as he makes his start against Arizona on Wednesday, I’ll be watching!

Photo by Kiyoshi Mio/Icon Sportswire

Fantastic piece, and great layman’s explanation of SSW. Well done sir.

agree 100%. This type of piece is why PL is the fist fbb site icheck every day.

Such a well written article ive marked my calender to watch a guy i had never heard of 15 innings ago…