I’ve been reading baseball analytics websites since 2016. Sites like FanGraphs, Baseball Prospectus, and PitcherList have been my safe space (is that a little sad? Maybe?) for a long time. Now that I have the chance to write about the sport, I often take inspiration from past articles that struck me as interesting.

There have been so many extraordinary pieces written since I started my fandom, but there is one that I always keep bookmarked to remind me of the creativity I strive to emulate when writing about baseball. The piece was written by Carmen Ciardiello back in August of 2021. The article is titled ” The Benefits of Changing a Hitter’s Eye Level,” and Carmen came away with the finding that “pitchers are most effective at inducing swinging strikes when they alter locations up and down.”

The article made me ask further questions (the sign of a great article, IMO) and inspired me to write the article you’re currently reading. Pitch models weren’t as popular in 2021 as they are now, yet I couldn’t help but ponder how much this sort of location sequencing (as I’m calling it) can help explain the gap between “stuff” and results. As they are all the hype these days, pitch models such as PLV, PitchingBot, and Pitching+ do an excellent job at predicting results, but they aren’t batting 1.000. Take Alex Cobb, for example. Excellent peripherals back his 3.09 ERA, yet the supermodels (as I have now coined them) don’t have a great answer for his production.

(The average for each component of Stuff+ is 100. The average for each component of PitchingBot is 50.)

This article will try to figure out what the deal is between Cobb and the supermodels with an emphasis on location sequencing. I should preface my work with a few things. First, there’s a reason these supermodels aren’t batting 1.000. They aren’t always correct, and they are not the end-all-be-all.

Second, Cobb may be getting lucky, and regression could be on the horizon. I mentioned his solid peripherals, but he does own a 4.09 xERA alongside an 81% LOB rate. I’m not sure how the rest of his season will go, but that isn’t really what I’m shooting for here. I’m more interested in the general disagreement between pitching models and results – Cobb is simply my test case. With that said, let’s begin.

First, Cobb is a three-pitch pitcher, relying primarily on a sinker, curveball, and splitter. If that feels like a super niche pitch mix, that’s because it is. There are only six qualified pitchers who throw sinkers and curveballs as their main offerings (say, 40% sinkers & 20% curveballs). In this age of pitching development and optimization, you don’t often see pitchers who throw sinkers and curveballs…. and then a splitter on top of it. Heavy supination pitchers (non-efficient spinners of the ball) often choose a slider to complement their sinker.

Moreover, the only other pitchers who throw at least 15% splitters and curveballs are David Bednar and Jhoan Duran, and they’re both high-leverage relievers. In this sense, Cobb is a unicorn, and I suspect it helps him keep an advantage over opposing hitters. Still, it’s not completely easy to quantify the said impact. That’s an article for another day. We can, however, investigate pitching models and poke holes in their accuracy on individual pitches.

Eno Sarris of stuff+ has mentioned that changeups are the most difficult pitch to predict from a pitch modeling perspective. They take the longest to stabilize of all pitch types, which is a nerdy way of saying you need to throw a lot of changeups to trust the stuff+ numbers more than the results of the pitch. For example, you can trust fastball stuff+ a lot faster than you can changeup stuff+. Cobb’s offspeed pitch is called a splitter, but the idea is the same. Again, the pitch models aren’t super high on Cobb’s splitter.

Naturally, the splitter has been his best pitch! Its 63% ground ball rate this season ranks in the 85th percentile among pitchers who have thrown at least 150 offspeed pitches. Moreover, the pitch has induced 25% ground balls with a launch angle under -13 degrees, a mark that means a high probability of an out. Its -10 run value makes it the fourth most valuable offspeed pitch of the season, behind those of Merrill Kelly, Erik Swanson, and Logan Webb.

This isn’t a hot streak for Cobb’s splitter, either. The ground ball rate is in the 91st percentile since the beginning of last season. It’s a plus pitch, point blank. So what beef do the models have with Cobb’s splitter? Well, I don’t know.

As I mentioned earlier, changeups are really weird; they “see some of the widest spread in Pitching+ largely due to the fact that they’re heavily reliant on velocity and movement differences compared to the primary fastball.” Therefore, stuff models may have a tough time nailing down changeups because their effectiveness is closely tied to an entirely separate pitch. It’s clear, though, that the gap between the efficacy of Cobb’s splitter and the respective models’ perspectives on it is large. The pitch, which accounts for 38% of Cobb’s arsenal, makes up the majority of the pitch model disparity.

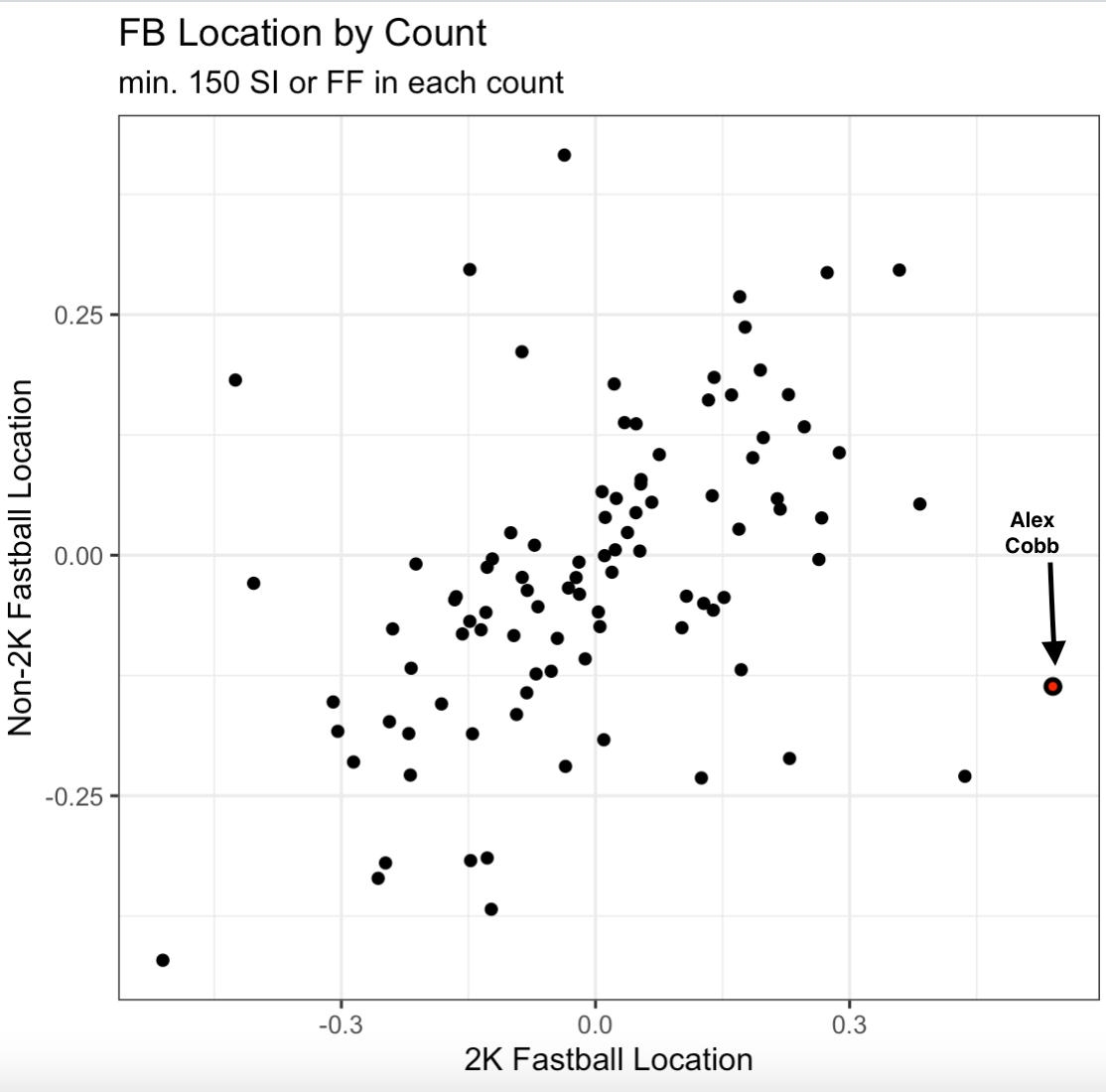

That’s the short answer. The supermodels think the splitter should be an average pitch, yet it has been the pitch anchoring a 1.6 fWAR campaign. Boom. Done. Except, it’s possible there is something else. Let’s get back to the location sequencing idea inspired by Ciardiello’s article on changing the hitter’s eye level. Inspired by his article, I wanted to see which pitchers, if any, utilize location sequencing to their advantage. Specifically, I ran a query that found which pitchers alter their horizontal fastball locations the most with and without two strikes. Alex Cobb’s sinker owns the largest difference.

Working both sides of the plate is something you may hear from the color commentator on your favorite team’s broadcast, but they are often referring to multiple pitches that each work one side of the plate.

Cobb does it using only his sinker, which is really cool! I double-checked the data to make sure this wasn’t just a platoon thing where he throws to one side of the plate vs. righties and the other vs. lefties. Against right-handed hitters only, Cobb’s sinker owns the largest differential in horizontal fastball location in two-strike and non-two-strike counts. Cobb throws 47% sinkers vs. righties, too, so the sample is substantial.

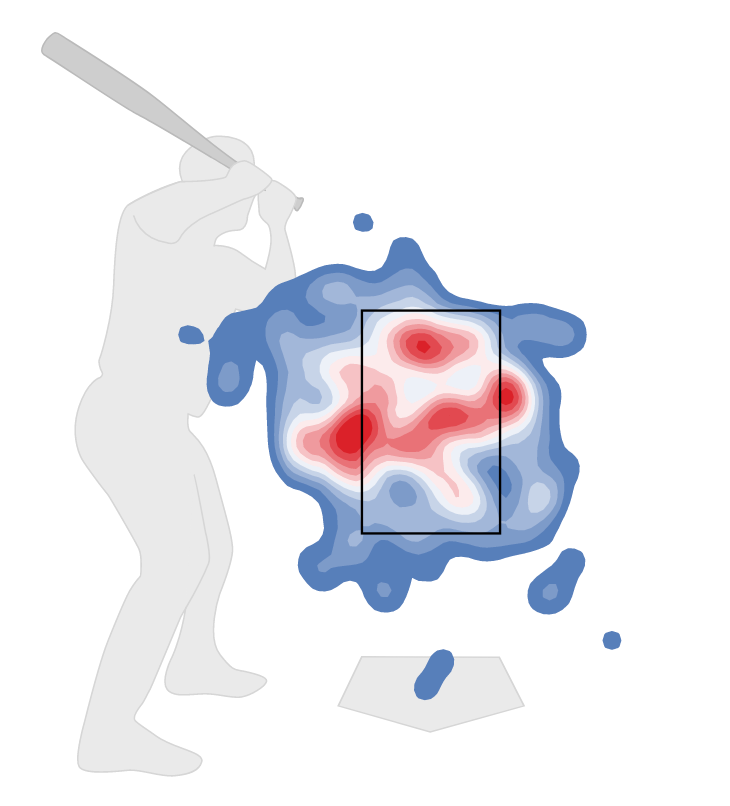

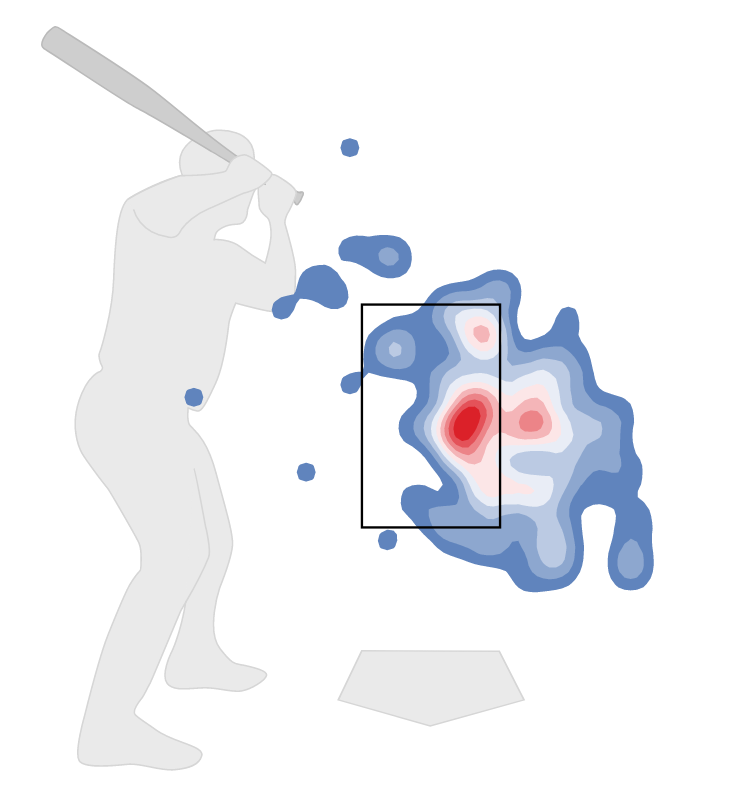

Before two strikes, Cobb throws his sinkers inside to righties, willing to sacrifice a called strike or whiff if it means weak contact early in the at-bat. With two strikes, a whiff or called strike is much more valuable, so Cobb paints the outer edge, looking to end the at-bat right there.

It seems to be an efficiency-focused approach on Cobb’s part; with zero or one strike, another strike doesn’t end the at-bat (duh). What could end the at-bat is a ground ball out, and Cobb is willing to risk contact being made if it means moving on to the next batter (Cobb has thrown seven innings or more in six of his fourteen starts this season). A foul ball is also a positive result. With two strikes, though, the value of a strike (and, thus, a strikeout) is far greater than a ball in play.

Furthermore, within any given at-bat, a righty could see what are effectively two different sinkers: one meant to jam early in the count, and one meant to paint the corner late. Here’s a really good example of that sequence at play. In an 0-1 count to J.T. Realmuto, Cobb throws his sinker in on the hands, inducing a foul ball.

The count is now 0-2. Cobb is going for a strikeout. Time to paint.

That’s some nasty arm-side run. I don’t know how much this element of Cobb’s game actually helps him. It feels almost impossible to put a number on it, but I think it’s worth considering what this tactic does to the psyche of a hitter.

Hitters often approach pitchers by hunting a window or zone. It’s an idea that was brought to my attention last season when Harrison Bader went on MLB Network to discuss his recent success. Against a right-handed pitcher like Justin Verlander, Bader mentioned how he’s looking for a “fastball up in the zone and a slider off of it.” Each pitch has an area of the zone that hitters expect it to be delivered in. Consider the Verlander slider and where Bader expects it to be located: down and away is optimal, but down, in general, is what both the pitcher and hitter are looking for. The fastball, as Bader said, is going to be elevated.

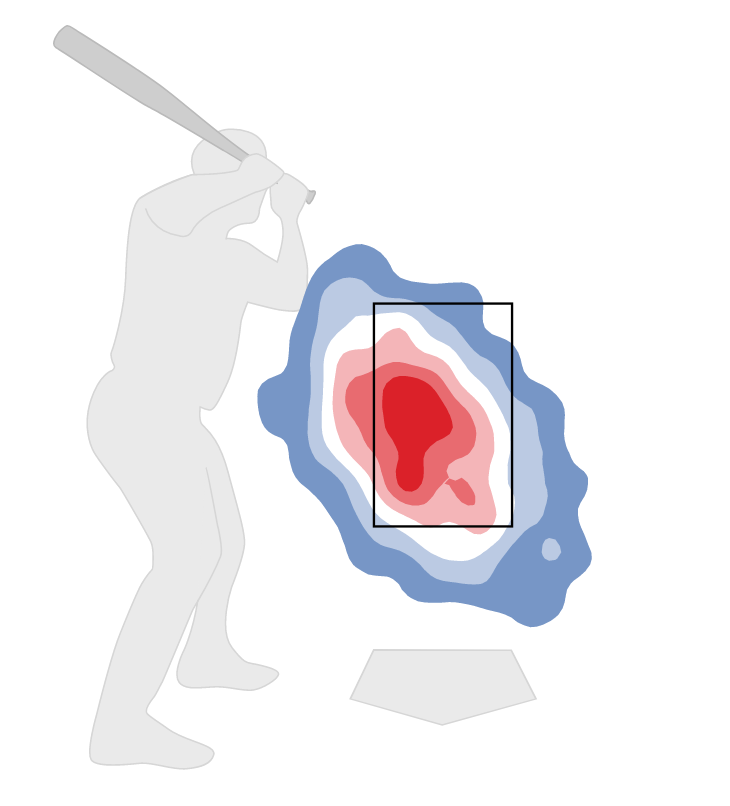

If the pitches aren’t in their respective optimal locations, it’s almost always a mistake by the pitcher. It’s why Cobb’s sinker location is so odd. He’s intentionally altering his sinker location such that hitters don’t know what to expect. Right-on-right sinkers are most often located on the inner half. Here’s a heatmap of where the Yankees, who have thrown the most such pitches this season, locate the pitch.

This location to righties is fairly similar to Cobb’s before two strikes (left image), but he completely flips the script with two strikes (right image).

The approach seems to be working for Cobb, whose sinker ranks highly in multiple areas. The pitch’s called strike rate ranks in the 91st percentile, its zone swing rate in the 98th (!!) percentile, and its ground-ball rate in the 88th percentile. One look at his .364 wOBA on the pitch may indicate that the supermodels accurately see the sinker as nothing more than average, but I’m more in favor of utilizing granular stats when evaluating individual pitches. The pitch’s production has outpaced the models.

I love when players do something different that could possibly lead them to success. Here’s the bad news for me: I dealt Cobb away in my fantasy league a few weeks ago, so am I rooting for him… really? A real moral dilemma. Regardless, I traded him away because I was looking at the supermodels that I have grown so reliant on the past few months. This article isn’t meant to imply that the models aren’t awesome (they are), but rather meant to promote further investigation the next time a pitcher is performing far differently than the models would have you think.

Graphic created by Aaron Polcare (@bearydoesgfx)

Great article. After watching 1,000s of baseball games over 45 years, I am convinced that pitching is all about sequencing. Keeping hitters guessing and off balance. Very little to do with the difference between a 94.6 and 95.8 mph pitch. All you needed to prove that was to watch Greg Maddux. Thanks again.