Last year, nine relievers had ADPs inside the top 100 and seven of them returned 25+ saves and seven are being drafted within the top 100 again this year. Of all the other relievers drafted outside the top 100, including the sixteen drafted between picks 100 and 300 alone, just four returned 25 or more saves. The price of the top relief arms has been trending up in recent years because they provide stability in an otherwise unrelenting sea of changing roles, injuries, and small sample size-related madness. Four additional players have moved into the top-1oo as we round into March to give us eleven relievers in the top 100 this year and, statistically, at least a few of them will have disappointing seasons, which become more and more costly to your team as you have to spend more and more draft capital to get the top guys. Here are five guys I’m avoiding at their current price.

AAV values are from NFBC auctions from February 15th to March 3, ADP are from Rotowire Online drafts from February 15th to March 3rd

ATC $14.7, AAV $20, ADP 54

When you see the word ‘bust’, you always have to keep in mind that it is always relative to draft cost. It’s tough for DL Hall to be a bust because you’re barely paying anything to get him. The bar for a guy like Jordan Romano, who you’ll likely have to spend a good amount of draft capital on, to be a ‘bust’ is relatively low. In this case, I’m not ready to make extremely bold claims like saying Nate Pearson will be the team’s closer by year’s end. The idea is intriguing, but there’s not quite enough evidence for me to predict a full collapse from Romano.

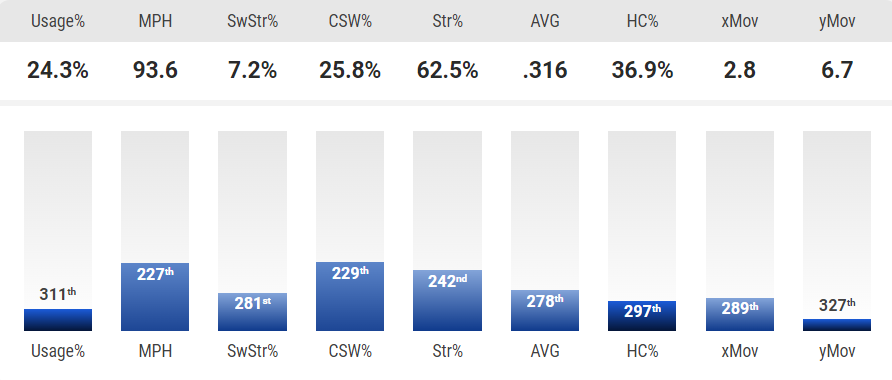

However, I see a couple of signs that potentially point to some struggles throughout the year. On the surface, we see a hard-hit rate that ballooned to nearly 46% in 2022, which was in the bottom 4% of the league, and a K-BB% that, at 46th in the league, was good, but not quite the elite figure you’d expect from a guy considered to be one of the league’s premier closers. As you dive deeper into the pitch level data, you can see some middling performance from his fastball in particular:

The low called strike percentage and horizontal movement combined with the high hard contact percentage paints the picture of a fastball that wasn’t extremely deceptive and, if anything, slightly less deceptive than last year. The average velocity, swinging strike rate, and CSW were all slightly slower than in 2021 as well.

Despite this, the barrel rate on his fastball went down from 10.8% to 5.7% and the HR/FB rate went from 13.9% to 3.1%. Perhaps upping his slider usage by about 15% from 2021 to 2022 allowed his fastball to play up a bit more, but it’s a tough argument to make that it would be responsible for such a drastic reduction in home runs, especially when his hard hit rate spiked. On top of this, Romano took a while to ease into the season in 2022 with his average fastball in April and May sitting at 96.3 mph before ramping it up to 97.5 for the final five weeks of the season.

If Romano again takes his time getting ramped up for the season and throws his fastball averaging around 96 to begin the year, there’s some potential for home runs to plague him in the first few months. As his velocity ramps back up, I don’t see any reason why he couldn’t regain his form as his slider is still pretty dominant, but the fastball is vulnerable enough that another dip in velocity like that makes it a pretty hittable pitch.

Given his high hard-hit rate as well, he’s vulnerable to the new shift rules forcing him into a few extra hits or preventing the Blue Jays from being able to effectively cover up Bo Bichette on defense.

Overall, I believe in securing one stable closer in my drafts because the pickings after pick 100 are so volatile and unpredictable. However, among the six “$20 closers” this year, Romano is likely the one I’d be least willing to drop $20 or a pick in my first 5 rounds on.

I think the fastball could end up being pretty vulnerable this year and, while the changes in the Rogers’ Centre park dimensions seem pretty neutral for now, it’s just another element of risk that should be factored into his price. With the sample size these guys work at, it only takes a few home runs to secure a mid-3s ERA for the year instead of a mid-2s, and the possibility of a hittable fastball leading to home runs early in the year has me concerned enough to call him a potential bust.

ATC $9.5, AAV $14, ADP 96

It was a tale of two seasons for Clay Holmes. On July 1st, he had a 0.49 ERA in 36.2 IPs with fourteen saves, seven holds, and four wins. He had an 82.4% ground ball rate and a -10 degree average launch angle during this time. Batters could only beat balls into the dirt against him. From that point on, Holmes battled command issues and a shoulder injury to the tune of a 5.33 ERA in his final 27 IPs and a 12.3% walk rate compared to 3.6% through July 1st.

It’s a bit of a “the chicken or the egg” conundrum. Did his shoulder issues cause command issues and lead to the poor performance, or did he start losing command and push himself into an injury as he tried to make adjustments to get his command back? The truth, as it often does, lies somewhere in between those two extremes. The unfortunate part, however, is that the midpoint is not very compelling given his draft day price.

Holmes is another pitcher who features a pretty high hard-hit rate at nearly 44% in 2022. He got away with it by being the best in the business at keeping the ball on the ground, but, remember, because of shift rules, hard contact on the ground is just a little bit worse for the pitcher and better for the batter this year than it was last year.

Second, PLV really thinks he overperformed with his sinker last year. It measures him in the 99th percentile for hit luck and gives him a PLA of 4.10, a wholly pedestrian figure. For a pitch that he throws 80% of the time, that doesn’t necessarily sound like an elite reliever.

The Yankees have several options that seemed more intriguing for at least part of 2022. Michael King looked dominant before fracturing his elbow and seems to be on track for Opening Day. Lou Trivino has closer experience and was excellent in the second half for New York. Aaron Boone has already said that “several guys will get saves” for New York this year, so there seems to already be some flexibility in Holmes’ role. If the command issues return, he won’t have as much leash as some may think.

ATC $6.2, AAV $11, ADP 131

I already wrote about Alexis Díaz earlier in the offseason and my thoughts on him haven’t changed that much since. With a 54.5% fly ball rate last year, fourth highest among qualified relievers, he can be described as an extreme fly ball pitcher who pitches his home games in the most hitter-friendly park in the league not named Coors. Before even looking at his stuff, that type of profile carries a significant amount of risk.

His pitches, at their core, are good offerings. A 15% swinging strike rate on his fastball and a 22.6% swinging strike rate on his slider are both pretty good. Nasty? I wouldn’t go that far. But good. He did a good job limiting hard contact last year, but still had a 7.5% barrel rate which, in a park like Cincinnati’s, often translates into more than five home runs across the entire season.

Walks are also an issue for Díaz who walked nearly 13% of the batters he faced. On its own, a walk rate of 13% isn’t killer. But it can be if you combine walks and home run risk and poor team context. In addition, we’ve seen plenty of research that there’s a hump somewhere around 95 mph where pitchers see significant improvements if they’re able to surpass the hurdle and significant decreases in performance if they fall below the hurdle. At 95.7, Díaz sits precariously on the edge and dips in fastball velocity, even for just a few outings, could make his pitches even more prone to homers given his propensity to work up in the zone.

The Reds, as a team, haven’t had a set closer since the departure of Raisel Iglesias and it seems to be a part of the philosophy of the team and David Bell to not stick with a set closer, even when one is clearly better than their other options like Alexis Díaz was last year.

On a team that is looking to win around 60 games this year, splitting opportunities would especially hurt and the upside of 35+ saves seems extremely low. The home run risk from both his usage of a fastball without elite velocity to generate fly balls and his unfriendly home park means that there’s a potential for really bottoming out like Alex Reyes did in the second half of 2021. If you do chase your saves here, know that this is one of the earliest relievers being drafted who has a non-negligible chance to be a cherry bomb reliever and hurt your team more than help it.

ATC $7.7, AAV $8, ADP 137

Scott Barlow still has an excellent pair of pitches. The curve and slider grade out pretty well by PLV, Statcast’s run values, and Fangraphs’ pitch values. He threw these two pitches more than three-quarters of the time in 2022 and they were able to carry him to a 2.18 ERA that was generally supported by the standard descriptive measures. However, he lost 1.5 mph on his fastball from 2021 bringing him to 93.6 mph. Remember how I talked about that hurdle around 95 mph? Barlow fell on the wrong side of that in 2022 and the results were…. not great.

At that velocity, Barlow’s fastball simply doesn’t work. The easy answer is to simply cut it out. It’s 2023, plenty of pitchers establish with the slider and “pitch backward.” The most successful at that, guys like Andrés Muñoz and Edwin Diaz, have fastballs with elite velocity that prevent you from having enough time to identify spin on their slider. However, there are guys like Steven Okert and Taylor Rogers who establish with the slider and don’t have elite velocity on their fastball. The problem is they’re both lefties and use a fastball as their secondary pitch.

There’s no real blueprint for Barlow going slider/curveball and that’s because secondary pitches generally work because they play off the fastball. If the hitter knows that nothing faster than 85 mph is coming their way, you better have some extreme deception going on like a Tyler Rogers type, and Barlow’s 14.3% swinging strike rate slider, below-average league-wide, doesn’t indicate that type of deception is happening.

So, Barlow is stuck with this poor fastball that he hopes doesn’t get rocked too much so that his other two pitches can get him outs. It’s not a very inspiring plan of action. In addition to that, Barlow’s team context is not ideal. The best reliever on the team is possibly Dylan Coleman, whose slider sports a better PLV than Barlow’s and whose fastball sits 97/98, and the Royals decided to spend a few million bringing in Aroldis Chapman to compete for the closer role.

Barlow is also a UFA after this year, so add on top of the risk of losing his job the probability that, if he does do well and keep the role, his trade stock is likely to be high enough that KC would be willing to flip him for prospects. In order for him to keep his job the whole year, he has to be doing well enough to fend off Coleman and what’s left of Chapman AND the Royals have to be doing well enough to want to keep him on for a playoff push without bringing on depth to split closing duties with him. Seems like a long shot to me.

ATC $3.9, AAV $11, ADP 149

2022 was the year that Daniel Bard beat Coors. He basically ditched his four-seamer and went to a sinker/slider approach and delivered one of the best fantasy seasons for a Rockies closer in recent memory with a 1.79 ERA and 34 saves. Everything went right for Bard. His already good velocity bumped up another half-tick to 98 mph and his walk rate dropped to 10.2%. I don’t want to say that his 2022 season was undeserved. Maybe he didn’t pitch to a sub-2 ERA standard, but he certainly earned an excellent season. His stuff was gif-worthy at times and, more importantly, he stayed healthy all year. I was thrilled to see Bard have such an amazing year and earn an extension. I can’t, however, bet on him to do it again.

I had the hardest time figuring out why, other than “Coors bad,” I was having a hard time believing in Bard. All of his contact metrics were stellar last year. PLV loves his slider. The sinker/slider combo is a great narrative for why he revitalized his career. I just kept coming back to his swinging strike rate. He had just an 11.2% swinging strike rate for the year when most dominant relievers are above 15 nowadays. It also didn’t seem to match up with his 28.2% K-rate.

I looked deeper at where he was getting his strikes and saw a 19.3% called strike rate driving a lot of his counts forward. When you look at the ratio of swinging strikes to called strikes, the average among the top 60 qualified relievers in CSW from 2022 was 0.89. For every ten called strikes, there are about nine swinging strikes.

The top relievers get well above 1.0 (Edwin Diaz – 1.41, Emmanuel Clase – 1.21, Liam Hendriks – 1.25). Daniel Bard was at 0.59. This was the eighth-lowest among the top 60 relievers in CSW, meaning that he was the eighth-most reliant on called strikes for his success. Unfortunately for Bard, called strikes are considerably less sticky year-to-year than swinging strikes.

My fear for Bard for 2023 is a regression to the mean on called strikes leading to fewer strikeouts. His K-BB already isn’t elite at 18%, so anything that would lower that, like fewer strikeouts or more walks, and allow more contact in Coors could have some pretty serious results. Command is so key for Bard this year and, for a guy who historically has struggled to keep his command, I don’t feel comfortable betting on him to beat Coors for a second straight year. I would love to be proven wrong here, but I also don’t want to chase last year’s breakouts and feel-good stories.

Photo by Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)

Man, these were basically all the mid-tier closers I was targeting. Bummer.