Some moments you just don’t forget. One of those for me was when Roberto Pérez smacked two bombs in Game 1 of the 2016 World Series.

This stuck with me not because I’m a closet Indians fan, but because of how utterly random it was. Pérez’s power explosion came out of nowhere. He had to work hard to end the regular season with a .186 batting average. The Elias Sports Bureau even noted that it was the lowest regular-season batting average for a multihomer hitter in World Series history. To that point, Pérez had hit three homers in the regular season, and his career high had been eight.

That second homer went a long way and is burned into my memory. I remember thinking that this was a big dude, and maybe he had some latent power. Yet, Pérez thereafter seemed to go not with a bang but with a whimper. In 2017 and 2018, he hit .188 with a total of 10 homers, 38 runs, and 57 RBI. Accordingly, he slipped my mind.

This year, though, Pérez is steamrolling the catching competition. He already has 16 homers, 31 runs and 38 RBI with a .255 average. Yet, for some reason he’s owned in only 12.2% of ESPN leagues. Opportunity knocked when the Indians traded Yan Gomes to Washington on November 30, 2018. While at the beginning of the season Pérez was splitting time more evenly with backup Kevin Plawecki, Pérez’s bat has earned him the lion’s share of the plate appearances, with a career-high 76 in June.

So what’s going on here? And is it sustainable? As always, to answer these questions, we need to go deep.

Elevation

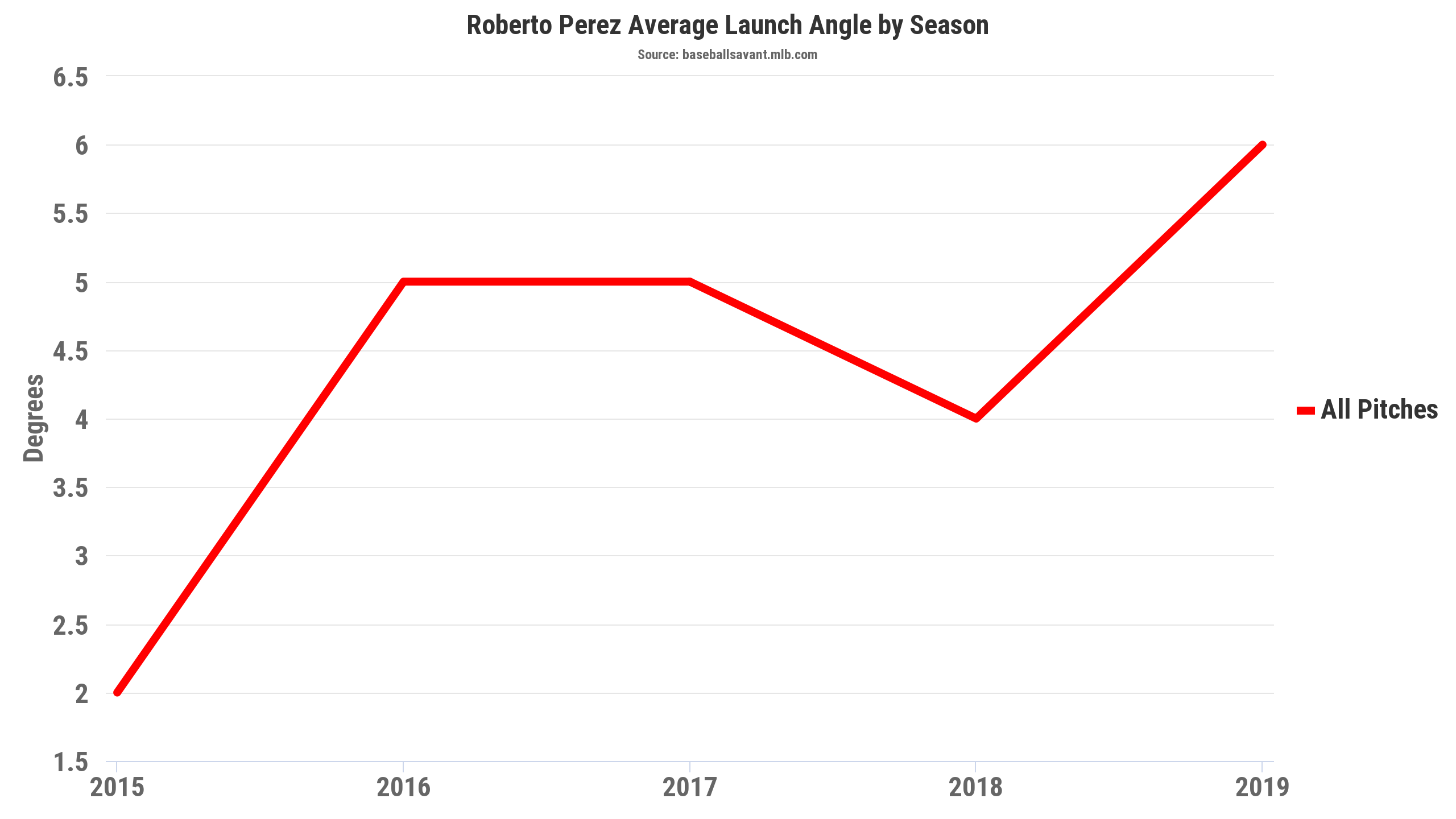

Sometimes, the easiest answer is looking at whether a player has joined the fly-ball revolution. At first blush, results for Pérez are mixed on this front.

Sure, it doesn’t appear that Pérez is elevating much better than before. Going from an average launch angle of 5.3 degrees to 6.6 degrees won’t really move the needle into slugger territory, and doesn’t explain why Pérez has experienced a massive power surge. Likewise, if you just looked at FanGraphs’ batted-ball types, you’d see that Pérez’s fly-ball rate has decreased from 35.5% to 32.2%.

Yet, that fly-ball rate includes infield flies, which Pérez has dropped from 13.2% to 6.5%. He may have a lower fly-ball rate this season, but he’s hitting better fly balls. Indeed, according to Baseball Savant’s batted-ball classifications—which exclude pop-ups from fly balls—Pérez is hitting a career-high 24% fly balls, which is above the MLB average of 21.9%. Houston, we have liftoff!

Raw Power

This is my favorite part of most of the articles I write. If it were as simple as a guy hitting more fly balls, I probably wouldn’t put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) in the first instance. But it never is.

A quick trip to one of my favorite sites for evaluating hitters, Statcast’s exit velocity and barrels leaderboard, will help us discern what Pérez is doing differently this year. His 95.7 EV on fly balls and line drives is impressive, ranking 53rd-best in all of baseball. However, as Nick Gerli astutely pointed out, line drives are basically valuable no matter the velocity with which they’re hit, whereas the value of a fly ball is highly dependent on exit velocity. Thus, removing exit velocity on line drives from the EV on FB/LD metric provides a better representation of true raw power.

| Season | Exit Velocity on Fly Balls | MLB Rank |

| 2016 | 93.8 mph | 61 |

| 2017 | 92.1 mph | 163 |

| 2018 | 91.0 mph | 257 |

| 2019 | 97.9 mph | 8 |

Isolating just Pérez’s fly-ball exit velocity shows that it’s up nearly eight ticks over last year. He hits fly balls way harder than in prior seasons. He hits them harder than nearly every other hitter in MLB. In fact, he’s only behind one other catcher: Jorge Alfaro.

| Season | Brls/BBE% | MLB Rank |

| 2016 | 6.0% | 237 |

| 2017 | 6.6% | 216 |

| 2018 | 5.9% | 243 |

| 2019 | 12.7% | 72 |

Pérez’s increase in barrel rate is dramatic too. He has more than doubled his 2018 mark. In fact, he sits fourth among all catchers, behind only Jason Castro, Mitch Garver, and Gary Sanchez. Of course, unlike the first two guys, Pérez isn’t in a timeshare.

Impressively, Pérez has not been dependent upon short pulled fly balls for his 16 homers. His pull rate according to Statcast is a meager 28%, well below the league average of 36.4%. And as I’ve noted before with respect to Jose Ramirez, pulled fly balls can be a fickle beast, depending on how a hitter is pitched.

So where is this newfound raw power coming from? Maybe you can spot it for yourself. Here’s Pérez in the 2016 World Series on the left next to a still of Pérez just before he hit a home run this season:

Besides the loss of a gratuitous amount of eye black, I spy two changes. First, Pérez is standing taller in the batter’s box. I’ve noted this before with respect to Freddie Freeman and Eugenio Suarez. For consistency’s sake, I’ll provide the same reasoning as to why this could be the cause of Pérez’s power surge:

When you’re leaning over, you fall into your swing, forcing your body to slow itself down in order to regain balance, and diminishing your bat speed.

With better balance, Pérez should be able to stay true through his swing and move through the hitting zone more quickly.

But Pérez has also lowered his hands. Now, they’re level with his front shoulder instead of his head. As former player and hitting coach Matt Stairs has discussed, the idea behind this swing change is to start lower in order to be quicker to the ball. Instead of beginning with your hands up and then bringing them down to start your swing just to bring them back up again to load, you start low and go straight to the baseball. There’s one fewer superfluous movement, which increases bat speed and shortens up the swing.

Of course, the juiced ball doesn’t hurt either. And with an emphasis on fly balls, standing taller in the box, and lowering his hands, Pérez is now able to hit for impressive opposite-field power even off good pitching:

https://gfycat.com/spectacularachingindianjackal

That’s impressive stuff that we don’t typically expect from a catcher. Certainly not one with a career-high eight homers coming into the season.

Contact Ability

His contact ability, however, tells a different story. Pérez has a 30.9% whiff rate and 28.2% strikeout rate this season. Plugging his whiff rate into a regression formula derives about a 26-27% expected strikeout rate. Though he’s slightly underperforming his expected strikeout rate, given that he’s a passive hitter (37.9 Swing%), he’s likely to continue to do so by a marginal degree.

Ordinarily, I write for traditional 5×5 categories leagues. But I’d note Pérez is more valuable in OBP leagues given his .344 OBP and 11.5 BB%. This is no surprise given his excellent 22.4 chase rate. As for his batting average, it’s important to consider his Statcast batted-ball profile.

| Metric | Roberto Pérez | MLB Average |

| GB% | 48.7% | 45.5% |

| FB% | 24.0% | 21.9% |

| LD% | 22.0% | 25.5% |

| PU% | 5.3% | 7.1% |

| Pull% | 28.0% | 36.4% |

This season, Pérez’s batting average is .255 and his BABIP is .295. His low pull rate makes him less susceptible to the shift, and his low pop-up rate means he’s minimizing the least valuable contact. Combined with an elevated ground-ball rate, this means he might continue to muster a decent BABIP—though I expect it’s still slightly inflated given his career-high fly-ball rate (fly balls rarely land for hits) and the BABIPs from 2017 and 2018, respectively: .266 and .257. Perhaps his new true talent is represented by a compromise .275 BABIP.

When his BABIP falls, it will be difficult for Pérez to continue besting his .242 xBA given his strikeout rate. Though he’s certainly no black hole in the category like some other catchers, he may be more like a .245 hitter than the .255 average he maintains today.

Conclusion

Right now, Pérez is on about a 60 R/30 HR/75 RBI/0 SB/.250 AVG pace. That not only plays at the position, but also would be an excellent option even in standard 12-team mixed leagues. Besides Sanchez, J.T. Realmuto, Willson Contreras, and Yasmani Grandal, there are no other catchers I’d drop Pérez to pick up. Perhaps Omar Narvaez and Christian Vazquez continue their breakouts, but I’m not sold. Pérez has nearly doubled Vazquez’s barrel rate and has more than doubled Narvaez’s, and if those guys revert to empty batting averages, then they’ll retain value in only the deepest of leagues.

Better yet, Pérez has made real changes to his approach at the plate, and the results are supported by his new career-high home run total—set only about a third of the way into the season—with excellent peripherals to boot. It’s difficult to tell how some of this season’s power breakouts will fare next year given that it feels like any of us could hit a home run these days, but I believe that, in Roberto Pérez, a fantasy star is born.

(Photo by Frank Jansky/Icon Sportswire)

Great write up. Keep them coming!

Thanks, Gary!

I would much rather have J. Phegley .I enjoy your work, thanks.

Really? Regression has hit phegley HARD. Cut bait if you haven’t already.

Get your stream on.

R. Perez or D. Jansen in an OBP league?

R. Perez, D.Jensen, Y. Molina ROS in an OBP league?

Pèrez!

Pèrez

Hey– with Danny Jansen seemingly breaking out, would you still drop Jansen for Perez? tx…

Yup!

Ramos or Perez in an obp league? Who would you rather have ROS?

Pèrez. I dropped Ramos for him a couple months back and am no worse for the wear

I think you are using the term “star” awfully loosely. Simply having a season in the upper end of the catcher production doesn’t make you a star. The top catcher is probably not a star in my book. The reason he goes unowned is that what he has done isn’t all that valuable – retrospect often makes things look better than they are. It may be better than the rest, but it isn’t a difference maker probably. Streaming is not that far behind. It is the peak Buster Posey types that move the needle, but upper tier C production is not that far ahead of streaming options. I think he is a fine option, but far from a star. Catchers look relevant for a fraction of a season every year and it just doesn’t prove to be sustainable more often than not. Last year it was PIT catchers and this year they look like pretty replaceable options. If I am looking for red flags it would be 5 2B with 16 HR – that kind of ratio is what it looks like when you are getting lucky. Put another way his XBH are very similar per game played to 2017. In my experience, XBH usually provide a lot of insight into sustainable production. You don’t just magically change 2B into HR – what you want is more well hit balls and that isn’t clear yet. It doesn’t mean he isn’t a new man, but 90% of the time we get carried away with catchers are we get too excited about how much a hot streak puts you ahead of what average C production looks like. The downside to committing to a mediocre option is that you miss out on streaming – so you want to be careful about thinking a C is special. Even if they are, injuries are never far away.

It took Nick Gerli to explain that line drives are the most productive swings? Everyone already knew that – I don’t see how you can cite a source on that. Be sure to mention that theKraken explained to you that the sky is blue and water is wet haha.

In regard to the Suarez lean theory. That isn’t how it is – he might feel like that works for him, but it isn’t that simple – if it were then everyone would stand straight up and they don’t. If that were absolutely true, then that would imply that everyone who leans over is doing it wrong – I don’t believe that is the case. You don’t want to mistake what works for one person as the way everyone should do it. You also can’t prove that it isn’t mental with Suarez. Hitting MLB pitching isn’t about peak bat speed – its about consistency. Its kind of interesting to talk Suarez at the moment because his power is up a tad but everything else is down – I am not sure that his adjustments have been positive. More Ks are not a mark of balance. Just anecdotally looking at this year, it looks like he has traded consistency for a few more HR which is a bad trade in my book. Hitting balls off of a tee for distance and standing straight up would probably be beneficial, but real hitting isn’t about maximizing leverage – a HR derby is closer to that. I am not sure that I even believe that standing a tad more upright increases balance – I am sure it is more complicated than that and probably depends on many other factors. You just really want to go spreading subjective analysis as truth in my opinion. Players should do what works for them and it changes over time. I like Suarez but I am not thinking he is exactly what hitters should be taking as the gold standard of how it should be done.