“X pitcher has been called up to make their MLB debut tomorrow.” Everyone scrambles to determine if the newest Major Leaguer is worth their time.

In 2023, it felt like the year of the rookie pitcher. From Taj Bradley to Grayson Rodriguez to Bobby Miller and everyone else in between, an exciting young arm seemingly debuted every week. It was easy to latch onto all of these promising pitchers after Spencer Strider’s electric debut and subsequent rise to stardom in 2022,

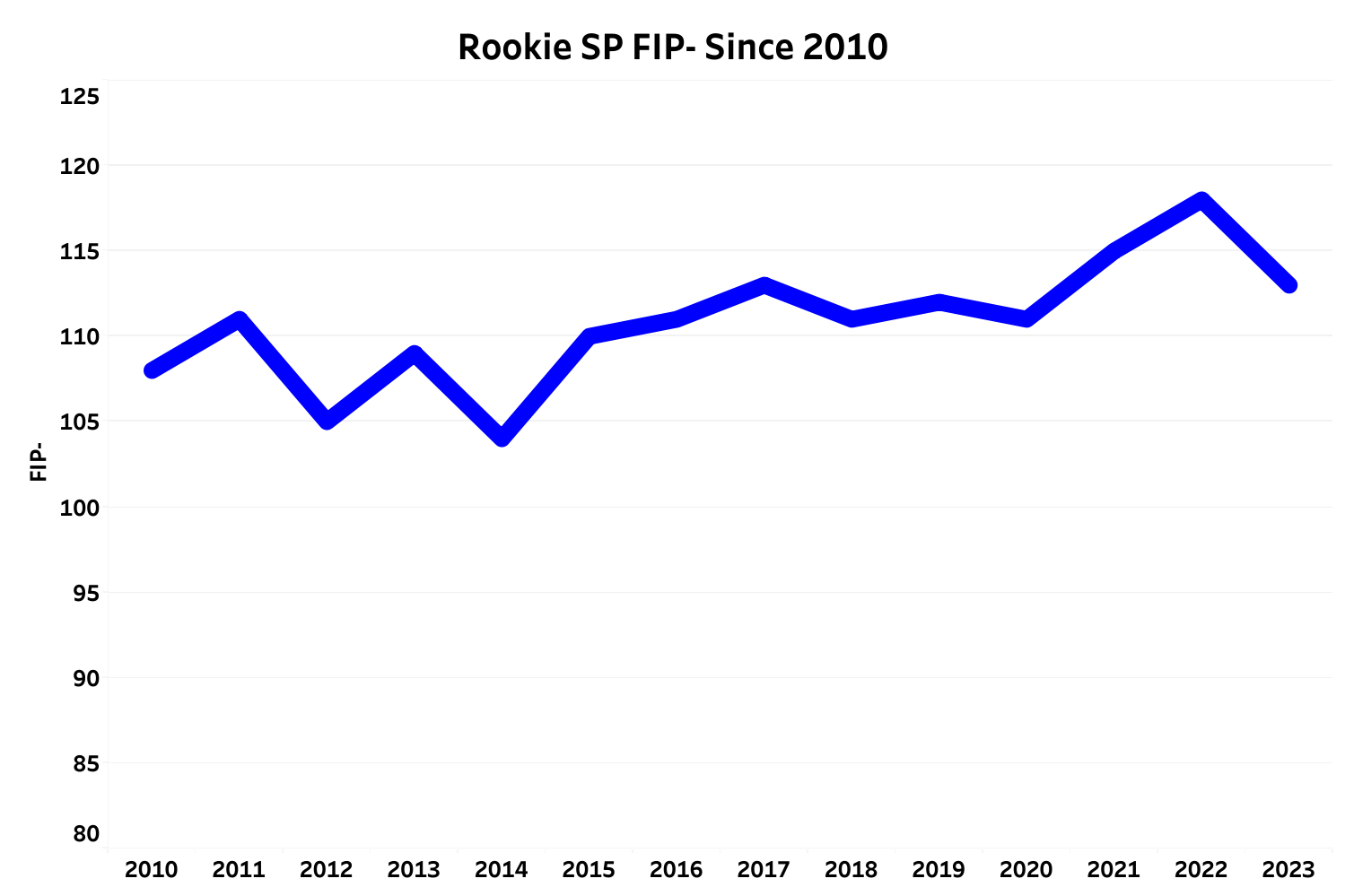

The proliferation of pitching data makes getting excited about young arms easier. However, that doesn’t mean the on-field product is any better. Since 2010, the 2023 rookie class posted the third-highest FIP- out of the field, only behind 2021 and 2022.

FIP- adjusts to the league environment each year, and it’s the counterpart to wRC+, so lower numbers are better for pitchers. Part of the trend can be attributed to the pandemic-affected season, which took away key development time for many prospects, but rookie classes were getting progressively worse before 2020, regardless. There was a step forward in 2023, but it still lags behind the pre-pandemic years.

For a long time, there has been an acronym that many abided by regarding prospect and rookie pitchers: TINSTAAPP. “There is no such thing as a prospect pitcher.” The research backs it up: prospect pitchers are more volatile than hitting prospects. With recent performance trends, reliance on rookie pitchers should be hypothetically decreasing.

Looking back on a few top prospects emphasizes how hard it can be to find a top prospect. Forrest Whitley, Nate Pearson, and Alex Reyes were all consensus top-10 prospects since 2017 and have only combined for 12 total MLB starts. On the other hand, Spencer Strider, Luis Garcia (HOU), and Shane Bieber, all of whom were not top-100 prospects, combined for 10.7 WAR in their respective rookie years across 67 total starts.

Finding pitching prospects is hard.

Rookie Stuff+

The public realm of baseball analysis has new tools to help identify which pitchers are better at sticking in the big leagues. That’s all to say that we can now shorten the gap between fans of the game and the teams themselves. One of the most intriguing stat we can look to for pitchers is Stuff+, which looks at pitch shape metrics and produces a grade based on its effectiveness.

While Stuff+ is quickly integrating into the world of baseball jargon, here’s Fangraphs’ primer (link) for those unfamiliar. In short, it’s normalized to the league, with a 100 being the league average.

I wanted to know what kind of pitchers saw the most success in the rookie season, especially in the last few years when pitch design has been king. Specifically, who performs better: pitchers with more balanced arsenals or pitchers with one or two really good pitches? There is a recent trend of teams not “wasting bullets,” meaning that once a pitcher gets an MLB grade on a pitch, the team will call them up.

I compared the Stuff+ and FIP of the last two rookie classes, focusing on how many pitches were above a certain threshold or their best pitch. The sample of players was limited only to starters (or innings thrown as a starter) and a minimum of 30 innings.

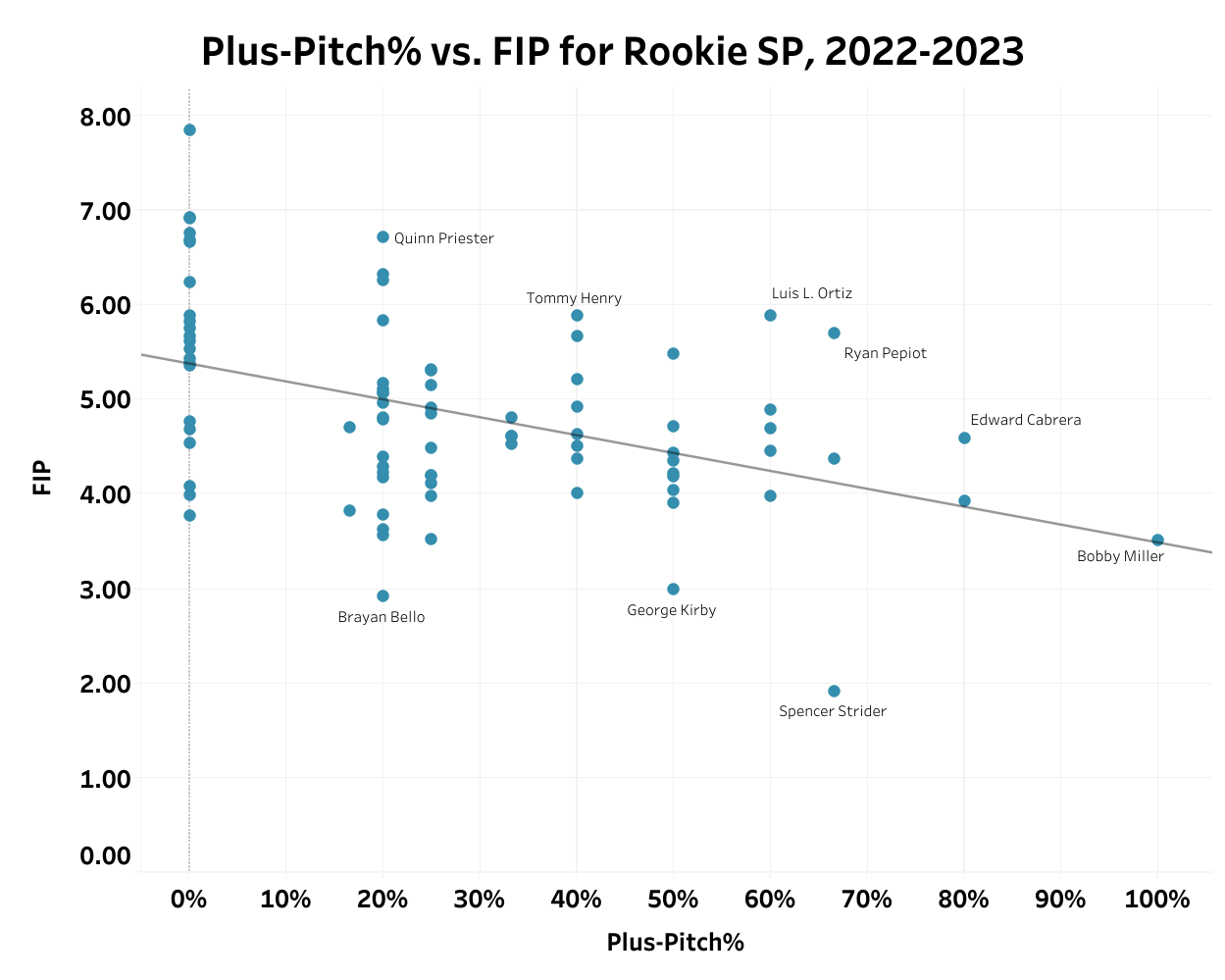

Plus-Pitch%

First is plus-pitch rate vs. FIP. Plus-pitch rate is my definition as the number of pitches above 105 Stuff+ out of the total arsenal for this exercise. This takes pitches slightly above average and beyond as considered “plus” to identify pitches that stand out compared to the league.

The resulting trendline has a statistically significant 0.19 r-squared, meaning that there’s a correlation between having more above-average pitches and performance. Bobby Miller is the only pitcher with all five pitches with a 105+ Stuff+ grade. Spencer Strider and George Kirby are the other two standouts, with at least 50% or more plus pitches. Conversely, Bryan Bello and Tanner Bibee are the best-performing pitchers with a sub-50% plus-pitch rate.

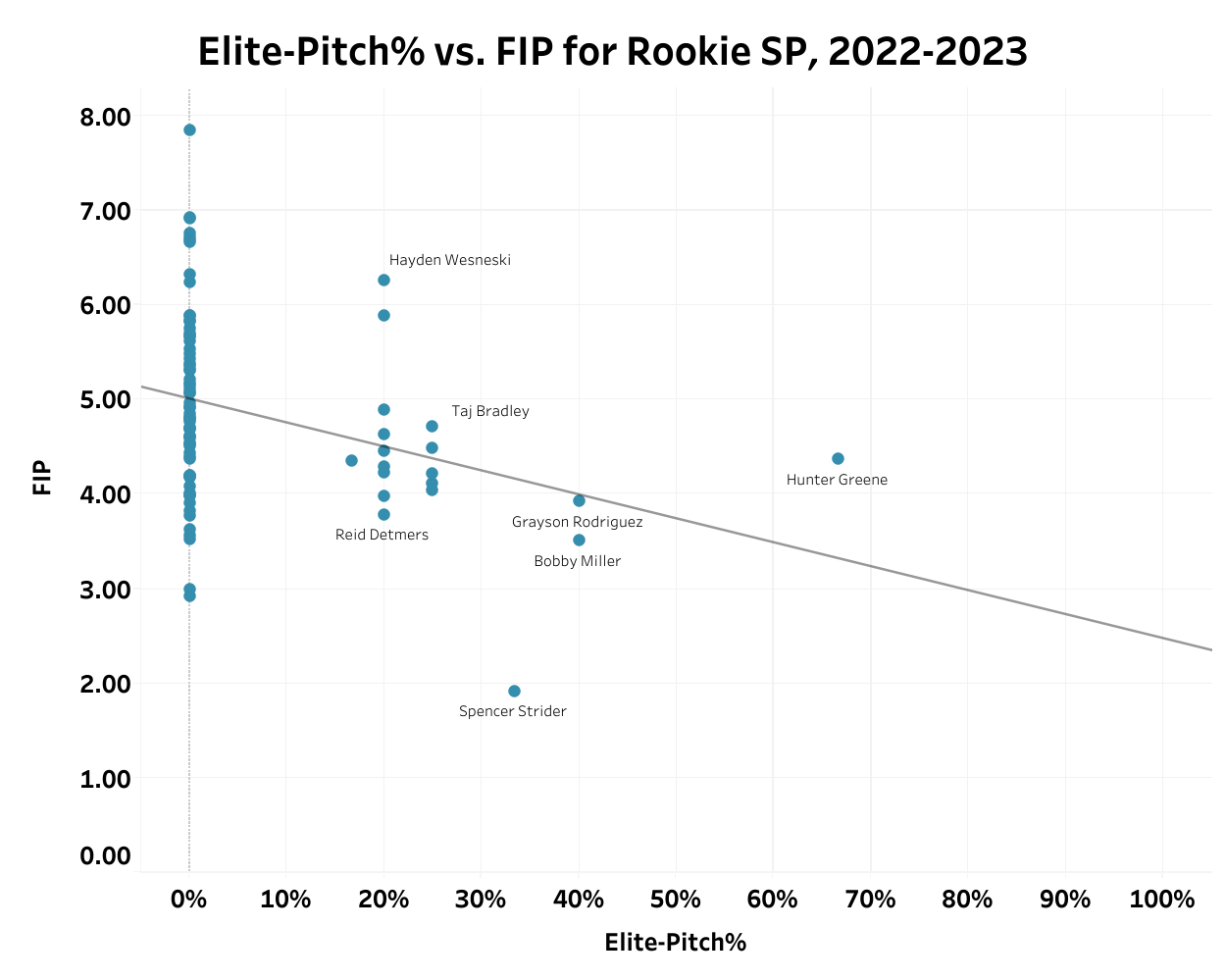

It’s generally intuitive that having more quality pitches leads to more success, but holding onto 1 elite pitch doesn’t guarantee success. Looking at a higher-tiered “elite-pitch rate,” which takes pitches above 120 Stuff+, there’s less of a correlation with FIP.

The result is statistically significant, at a .10 r-squared, but not as strong as the plus-pitch rate. The obvious standout is Hunter Greene with his fastball/slider combination, but the takeaway is that you likely need two elite pitches to succeed (see the Huascar Ynoa rule link). Strider, Miller, and Grayson Rodriguez are the three others north of 30% elite-pitch rate. The rest of the rookies with one elite pitch have produced a mixed bag of results.

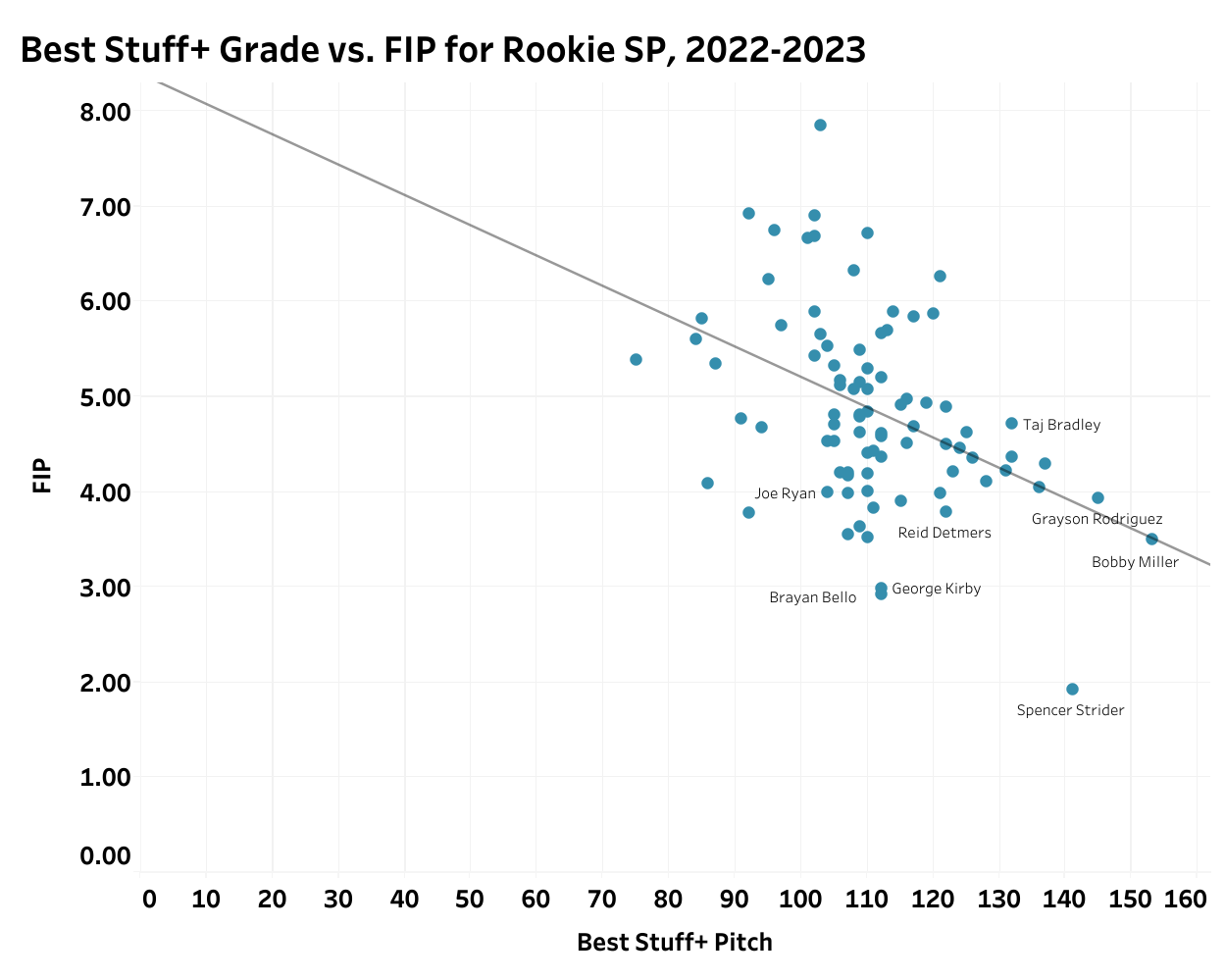

However, highlighting a pitcher’s best pitch yields a similar result to plus-pitch rate vs. FIP.

This has a statistically significant r-squared of .18, almost equal to the plus-pitch rate. Having one elite pitch can ensure one level of success, but having multiple elite pitches is not necessarily required. Instead, having one elite pitch and other sufficient offerings to fill out an arsenal can work.

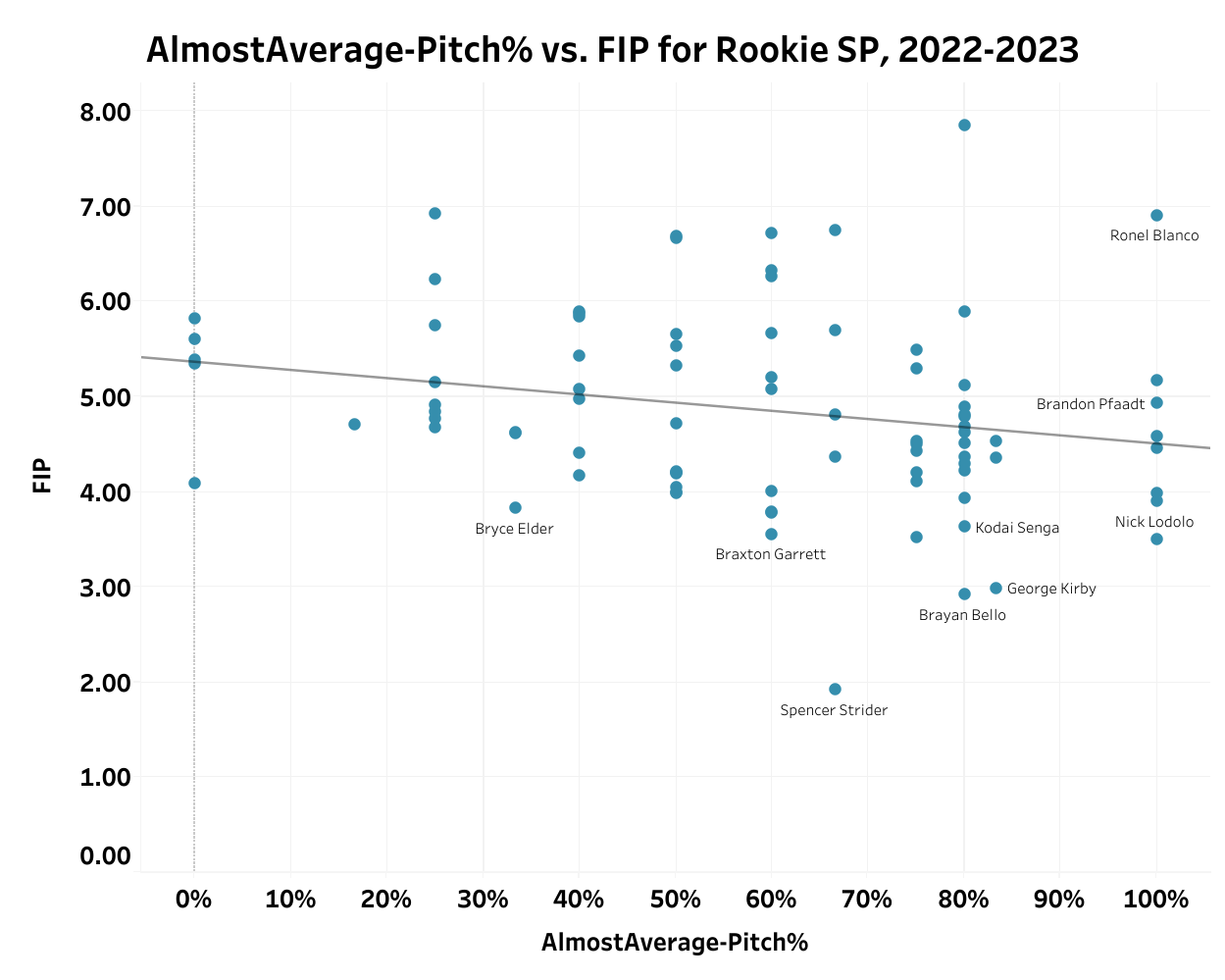

Rather than heightening the ceiling, we can also lower the floor. Looking at an AlmostAverage-Pitch rate (apologies for the rather uncreative naming convention), which is the number of pitches over 90 Stuff+, we can see if a less filthy arsenal with more pitches is successful.

This has an even smaller .05 r-squared value, meaning higher quality pitches outperform a higher quantity of pitches. Pitchers like Nick Lodolo and Kodai Senga appear on the far end of the spectrum with these parameters, but there is a lot more noise overall. Even at a 100% rate of AlmostAverage-Pitch rate, pitchers such as Brandon Pfaadt, Ryne Nelson, and Ronel Blanco have struggled significantly.

This isn’t to say that it should be a hunt for Stuff+ from prospect pitchers; an arsenal’s depth is important. The correlations between FIP and Stuff+ are not super strong, but they are not insignificant. It also ignores command, which is often another big development for rookies. There’s a reason Tanner Bibee or Braxton Garrett can succeed, but it’s much more volatile compared to the high-stuff pitchers.

When a pitcher comes up and flashes a plus pitch, it’s worth watching. Those players have the ability to build off a solid foundation rather than work up to one. When you see a unicorn like Bobby Miller debut, it is easy to see his path to success.