The St. Louis Cardinals might be exhibit 1-A of why sports probably shouldn’t have been played this year. They dealt with an out of control Covid-19 outbreak which sent multiple members of the organization to the hospital. Players were falsely slandered for it, and are now in the midst of playing a grueling 53 games in 43 days to make up for the lost time. That they’re 14-14 in spite of it is a heck of an accomplishment.

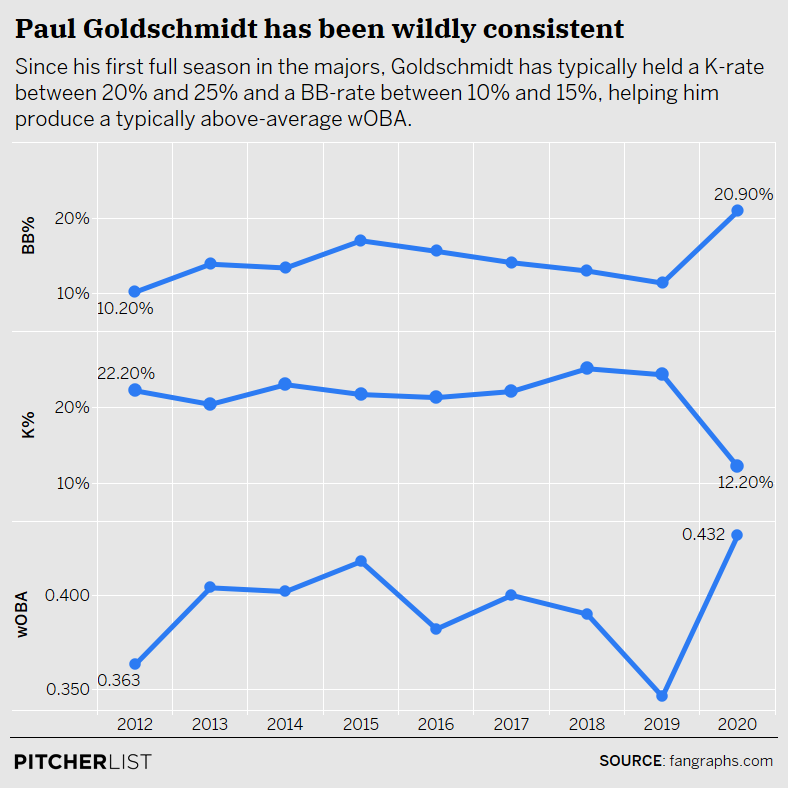

On the bright side of things, it looks like that down year of Paul Goldschmidt’s in 2019 might have been just that—a down year. Understandably, there was consternation under the Arch when Goldschmidt followed up his 5-year, $130 million extension with a 116 wRC+ that, while not bad in a vacuum (16% better than league average!), was the first time since 2012 it had dipped below 133. A year and change later, Goldy is slashing .337/.478/.517, with the middle number leading the entire league.

That league-best OBP is a hint at something new. Despite the excellent batting average, Goldschmidt isn’t slugging his way to a .432 wOBA. He’s only hit three HR so far this year, and his isolated power has declined for the third consecutive season to a career-low .180. On Statcast, his average exit velocity (87.3 MPH), hard-hit rate (32.9%), and expected wOBA on contact (.421) are all career lows since data began being collected in 2015.

Instead, it’s a preponderance of walks (career-high 20.9%) and a dearth of strikeouts (career-low 12.2%) that’s driving his resurgent production. This isn’t just a one-year bounceback, either. These career bests are coming on the hills of several consecutive seasons of decline:

(Graphic: Teddy Baines)

I’ll spare you the excruciating extended title metaphor—let’s just say that Reverend Run and Steven Tyler would be impressed with his walking. A general survey of Goldschmidt’s plate discipline rates won’t tell us exactly what he’s doing differently, but it’ll point us in the right direction. To start, he’s seeing 5% fewer pitches in the zone, which is obviously very important in terms of walking more and striking out less. Consequentially, he’s swinging at fewer pitches in general, and he’s been much more adept at laying off pitches out of the zone:

| Year | Zone% | Swing% | Whiff% | Chase% | 1st Pitch Swing% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 47.5% | 46.5% | 26.3% | 28.4% | 30.6% |

| 2020 | 43.1% | 38.2% | 20.3% | 21.9% | 20.0% |

| League | 48.4% | 46.6% | 24.4% | 28.2% | 28.3% |

(Source: Baseball Savant; all stats through September 2nd)

That tells us the combination of factors leading to booming walks and busting strikeouts, but again, it doesn’t tell us what Goldschmidt is actually doing differently on a pitch-by-pitch basis. The first hint comes in that big drop in first-pitch swing rate. Choosing to be passive or aggressive on the first pitch is often the bellwether of a general approach change, as has been documented with Ian Happ, Howie Kendrick, and Bryce Harper, among others. Goldschmidt too has been considerably more passive on 0-0 counts this year, which has combined with the mysteriously lowered zone rate to drop his overall first-pitch strike rate from a career-high 65% last year to a career-low 51% this year.

Over the course of a full season, that’s somewhere in the vicinity of 90 plate appearances that would go from either an 0-1 count or ball in play to a 1-0 count. As was the case with Harper and all the aforementioned, that’s definitely a good thing for Goldy. For his career, he’s got a .344 wOBA and .185 ISO when the count goes 0-1, and a .435/.261 wOBA/ISO split when he gets to 1-0. Granted, he has been excellent in his career when he does put the ball in play on the first pitch, batting .401 with a gaudy .480 wOBA. With pitchers now finding the strike zone on just 39% of first pitches to him so far this year, it’s a tradeoff he’ll be willing to make.

Mechanics

We’re still looking at more than just an approach change, though. He’s benefitted from seeing far fewer 0-1 counts than usual, but he’s hitting even better than ever when he does get there. His career wOBA on 0-1 counts is only .344, but this year, that number is all the way up to .399 in a 53-plate appearance sample that’s small, but not quite too small to matter.

What else is going on under the hood? we know he’s not really hitting the ball better than he was before, but if you go back to those plate discipline numbers, you’ll see that he’s whiffing a fair amount less. It’s quite possible he’s consciously trading power for contact. Let’s see if we can see anything different in his swing. Here’s a home run from 2019:

And another from a few weeks ago:

Just to be safe, let’s watch him missing on a couple of pitches over the plate, too. A groundout from 2019:

And another in 2020:

There might be some things we can’t see. Many of the minute factors that decide pitches, swings, and baseball games are impossible to see from a center field camera well. Overall, though, it looks like Goldschmidt is featuring more or less the same swing that got him here. If you squint, it looks like he’s tipping the barrel of the bat just slightly more towards the pitcher, and the bat is perhaps noticeably less vertical when he goes into his load. This certainly might be helping his contact ability, as it makes it easier for a hitter’s swing to get on-plane with the ball. But it’s not enough to explain the kind of broad shifts we’re looking at here.

Approach

We’ve already gone a little deeper into what’s happening to Goldschmidt on 0-0 counts. Now, we’ve also discovered that he’s hitting way better than usual on 0-1 counts. There hasn’t been any major swing change—this does appear to be almost entirely approach-based—and it seems likely that this approach extends further beyond his first-pitch swing tendencies. This chart is a bit of a mouthful, but it’ll help us look at how his habits have changed depending on whether he’s ahead or behind in the count:

(Source: Baseball Savant)

Let’s break it down column by column. As I suspected, he’s working with the count advantage a full 10% more than he was last season, almost entirely at the expense of plate appearances behind in the count. And once again, there’s that drop in zone rate, which I promise we will get to soon!

Swing and chase rates are where things get a little interesting. Last year, Goldschmidt’s approach was relatively consistent throughout the count, now swinging in any one advantage situation more than the other. That’s changed in both directions this year. He’s being even more aggressive when behind in the count, which is partially why he’s seen a 10% drop in plate appearances that reach two strikes. Can’t strike out if you don’t get to two strikes!

As would also be expected, that aggressiveness behind in the count has bled into his chase rate, going after more than a third of pitches out of the zone when the pitcher has the advantage. When he’s ahead or has it even, though, he’s got one of the most discerning batting eyes in the majors, ranking in the league’s top 15% by chasing just 17% of balls out of the zone.

There we have a more specific idea of what’s driving the Houston-area native’s on-base resurgence. He’s adjusted to seeing fewer pitches in the zone by letting pitchers walk him when they fall behind, and avoiding the strikeout when they get ahead by more aggressively leveraging his power (even as it’s diminishing) and contact ability earlier in the count.

Swinging and Taking on the Edges

Count leverage isn’t the only way we can look at the cat-and-mouse game between pitcher aggressiveness and hitter swing decisions. Let’s go take a look at Baseball Savant’s swing/take charts, which tell us how many runs a hitter added or lost on their swings and takes in certain areas of the plate. If we look at Goldschmidt’s 2019 chart, we can see that it was mostly pitches on the edges of the plate—what Savant calls the “shadow zone”—that dragged down his production:

If you look at the Run Value section on the far right, you can see that Goldschmidt actually added a run with his non-swings in the shadow zone, meaning his eye is good enough to make it a net positive when he passes on pitches there. When he swung, however, he was terrible, batting just .230 with a paltry .290 wOBA and .323 xwOBA and costing 15 runs. In 2020, that trend has (almost, kind of) reversed:

While his swing rates over the heart of the plate and the chase zone have seen a modest decrease corresponding with the general trend, he’s cut a full ten points off his swing rate on pitches in the shadow zone. And when he is swinging there, he’s been much more effective. Yes, he still has negative swing runs on those shadow zone balls, but that’s a reflection of game outcomes, not necessarily how well he’s actually hitting the ball. Nonetheless, his batting average on them when he puts it in play is a healthy .390, and a .358 xwOBA indicates that the .402 wOBA isn’t totally a fluke. Even if it’s not totally sustainable, the bottom line is that his swings aren’t negating 15-fold the good work that his batting eye is doing. When his bat does inevitably cool off in the shadow zone, he should be seeing an improvement just by letting his pitch recognition do more work.

On that note, let’s come back down to earth. I’ve been wrong plenty of times before, but I feel pretty confident in predicting that Goldschmidt won’t become the ninth player this century to eclipse a 20% walk rate in a (not, in this case) full season. The plate discipline is real, don’t get me wrong. It still says something that while his wOBA on those shadow zone balls has jumped 112 points this year, the xwOBA has gone up by just 35. He’s doing better when he swings, for sure, the degree of improvement is probably just exaggerated—as is everything else in this absurd season.

Perhaps tellingly, he’s also seen his BABIP swing from a career-low .302 in 2019 to .370 this year, which would be his highest since 2015 and second-best mark ever. But it doesn’t really square up with the downward-trending exit velocities and contact quality. Goldschmidt’s approach has undoubtedly changed, and he’s undoubtedly seeing better results for it. He’s also undoubtedly hitting out of his league right now, and the walks won’t be able to buoy him to top-ten production for long.

In the End…

Getting his walks and strikeouts back to pre-2017 levels will certainly prevent him from falling back into the crevice that swallowed his bat early last season, to be sure. It’s also fair to question whether this surge is masking the fact that the Goldschmidt who will be spending the next four-plus years in St. Louis might no longer be the .550 slugging machine he was for most of the 2010s. That doesn’t mean he’s not good—he’s still really good!—it just means that rather than thinking of this surge as a return to form, it might be more accurate to consider him to have rearranged his game a bit.

Which, finally, brings us to that drop in zone rate. It might just be unreliable luck. As far as I can tell, there’s not really a data-based explanation for it. Overall zone rates are up by a fraction of a percentage point this year, so even accounting for the switch to Hawkeye, it isn’t a league-wide trend. It’s not an unusual number by itself, and it sits squarely in the midst of other feared sluggers like Nelson Cruz, Aaron Judge, and Giancarlo Stanton. For something almost entirely out of Goldschmidt’s control, though? I wouldn’t count on this kind of deviation from the norm holding up:

(Source: Fangraphs)

Anything addressed in this article is subject to the same simple caveat: what happens if pitchers start throwing him more strikes? All that patience might bring some different results if pitchers decide to test it more. The underlying numbers on his hitting will be a cause for concern if he starts finding himself in fewer advantageous counts. This takes nothing away from how fantastic he’s been up to this point, but it’s a tenuous balance. There’s a reason only eight players not named Barry Bonds have broken that 20% walk threshold since 2000.

But that’s baseball. Any deciding factor of any given game can be broken up into twice as many factors and then twice more. Instinctually, my most feasible explanation is that opponents might just have less reason to pitch to him than ever. The Cardinals offense leaves much to be desired this year, though much of that is no fault of their own, to be clear. Perhaps Brad Miller’s maybe-legit breakout will change the calculus on pitching to Goldschmidt. Nonetheless, after having the benefit of hitters like JD Martinez and Marcell Ozuna behind him in recent years, there’s little reason for pitchers to attack him with much aggression now when they can pitch to Miller, Tyler O’Neill, or a struggling Matt Carpenter instead.

There’s no real way to back that up as far as I can tell, but again, that’s baseball. There are some things you can’t know without watching them happen. A player is never their stat line; if I was watching the Cardinals play every day, I’d probably have a clearer explanation for what’s going on in half as many words and charts. If pitchers continue to avoid the zone, we have some context for understanding what he might do throughout an at-bat. If pitchers start being more aggressive, we’ll get to see if and how he adjusts. And I’ll be just a little bit more invested the next time I do get around to watching the Cardinals.

Photo by Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)