Don’t look now, but Josh Tomlin is starting for Atlanta on Tuesday. Yes, that Josh Tomlin, who sported a 6.14 ERA and 7.17 FIP in 2018, the last time he sniffed a big league rotation.

Sounds about right, considering how far down the tubes this season has gone for the NL East. The Cardinals and Reds have been dominating COVID-related headlines the past several weeks, but on the whole, there’s an argument for the East having to this point borne the brunt of the league’s eye-popping (and utterly unsurprising) pandemic mismanagement.

What more do you need to know, other than that the Marlins are still in first place? Jokes aside, Atlanta currently sports a 13-9 record and is clearly the team to beat in the division, but not much else is peachy in the confines of the Georgia suburbs. Ronald Acuña Jr. and Ozzie Albies are IL-bound; Freddie Freeman’s slugging is at its lowest point since 2015; Dansby Swanson’s hot start appears to have been little more than that; and the Austin Riley/Johan Camargo tandem has been woefully unable to fill the hole left by Josh Donaldson.

On the pitching side, the names currently not in the rotation include Mike Soroka, Cole Hamels, Felix Hernandez, Mike Foltynewicz, and Sean Newcomb. Their next five probable starters are listed as Touki Toussaint, Tomlin, Kyle Wright, TBD, and TBD. Nothing is certain under pandemic circumstances, but needless to say, it’s far from ideal. If you had said this to an Atlanta fan a month ago, they’d probably be elated by the 13-9 record.

It’s pretty hard to be down on any disappointing or underperforming team given the state of the world, so let’s look at the positives, especially with regards to our Tuesday starter. On paper, it’s a big problem that Brian Snitker & co. are turning to Tomlin to start a meaningful baseball game. The last time he was an effective rotation piece, the Cubs were still the driest team in championship history.

Since starting last season in the Atlanta bullpen, however, it’s been a different story. After posting a respectable 3.74 ERA/4.49 FIP as a long man for the 2019 NL East champions, Tomlin has taken it to a new level early this year, allowing just 2 earned runs over 11.1 innings along with a typically stingy 3 walks and *squints* 16 strikeouts?

Wait, What?

If that seems a little odd off the top of your head, you’d be right! Tomlin is currently running a 38.1% strikeout rate along with a 30.8% whiff rate, both of which are blowing the doors off of his career highs. “Wait!” A baseball fan with a half-decent memory might say. “Since when does Tomlin strike people out? He’s a finesse righty who thrives on weak contact!” And that fan would still be correct! Tomlin’s fastball velocity still barely scrapes 88 MPH the lowest mark of his career. That’s not to be unexpected from a 35-year old with 1700 professional innings under his belt. What’s the story here?

After being ignominiously booted from the Cleveland rotation in 2018, it looked as if Tomlin’s career was ready to descend into the anonymity of Dave Bush, Randy Wells, and the other briefly successful right-handed mid-80s fastballs of yore. While he relied on his cutter more than usual last season, his renaissance in the Atlanta bullpen was accomplished with more or less the same five-pitch arsenal he utilized as a starter. This year, that’s not the case:

| Year | Four-Seam | Cutter | Sinker | Curve | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 27.90% | 39.00% | 5.50% | 22.80% | 4.80% |

| 2019 | 25.20% | 43.20% | 5.70% | 17.30% | 8.50% |

| 2020 | 10.80% | 52.70% | — | 31.10% | 5.40% |

Source: Baseball Savant

Ditching the four-seamer, which has sported an expected wOBA above .400 for three consecutive years, is almost certainly a good idea. Even with good command, 88 MPH fastballs with run-of-the-mill movement don’t last very long in the league. The changeup is nice in that most pitchers in any role should probably have an offspeed pitch in their bag of tricks. Relievers usually usually shorten their arsenals to maximize their best pitches; a surface level glimpse tells us that is what Tomlin has been doing here.

Maximizing the Stuff

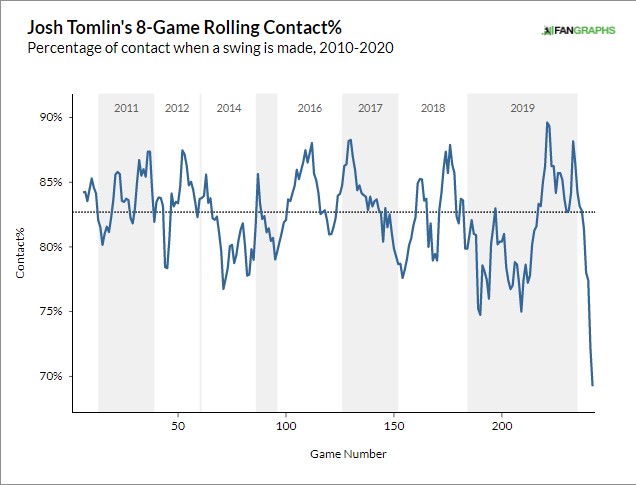

Before we dive further, though, let’s reset our focus. After a decade as a contact-oriented starter, Tomlin is looking poised to go bullpen Charlie Morton on us, at least in terms of strikeouts. Since we want to know how he’s doing that, it’s good to get a sense of whether he’s had stretches like this before. Precedent is important when looking at potentially drastic changes in pitcher profile. In this case, the answer is emphatically no. This is most certainly not a version of Tomlin that we’re familiar with:

Source: Fangraphs

Alright then! Using eight-game rolling rates isn’t ideal—eight games as a starter is a lot different than eight games as a reliever—but even using a less-aesthetically pleasing two-game rolling average shows the same thing: Tomlin has never missed more bats than he is right now.

A pitch-by-pitch look shows that the majority of the work is being done by his curveball, which has garnered a whiff on an even 50% of the 20 swings it’s drawn this year. By most measurements, it’s not a particularly exciting curveball, with an average amount of drop and subpar side-to-side movement despite an 80th percentile spin rate. It’s also been useful, if unremarkable, consistently generating average whiff rates and wOBAs throughout his career. Let’s see it in action this season—here it is getting the swing-happy Vladimir Guerrero Jr. to reach for a pitch he certainly shouldn’t have:

And here’s an excellently placed bender that juuuuust grabs enough of the plate to draw a lunging swing from Pete Alonso:

Those are fine pitches, but not the kind of thing that makes you go “woah.” The eye test aligns with the numbers; it looks like a perfectly good pitch, especially when commanded well, but nothing special. In a 20-pitch sample, it’s only three extra whiffs making up the difference between its current performance and the pitch’s meh-ish 35% whiff rate from 2019. At this juncture, a good or bad day from any given hitter or two might be the difference there. What else is there to see?

Let’s move on to the cutter, which has served as his primary fastball for the better part of five seasons now. Tomlin’s natural high spin is getting put to better use here than with the curveball, as the cutter drops a solid 3 inches fewer than the average cutter at his velocity while being supported by roughly average horizontal movement.

Unlike the curveball, which has a full ten inches fewer drop than it did in 2018, Tomlin’s cutter has remained essentially unchanged from his Cleveland days. Yet like the curveball, the pitch is drawing more swings and misses than ever, running a 27.1% whiff rate than would also easily be the highest of his career. Whence lies the secret sauce?

It’s hard to say. Even watching the two pitches work together—here’s a recent cutter and curve filled sequence to Mike Ford that resulted in a swinging strikeout, for example—nothing really stands out. David Laurila talked to Tomlin in-depth before the 2019 season about his time at Driveline Baseball and the repertoire adjustments that came thereof, but the sliders and changeups he discussed then don’t seem to have materialized in game action. And while tightly clustering a cutter and changeup turned out to be the key to Dallas Keuchel’s early season success, the numbers say that’s not the case with Tomlin.

Using Your Head To Get Ahead

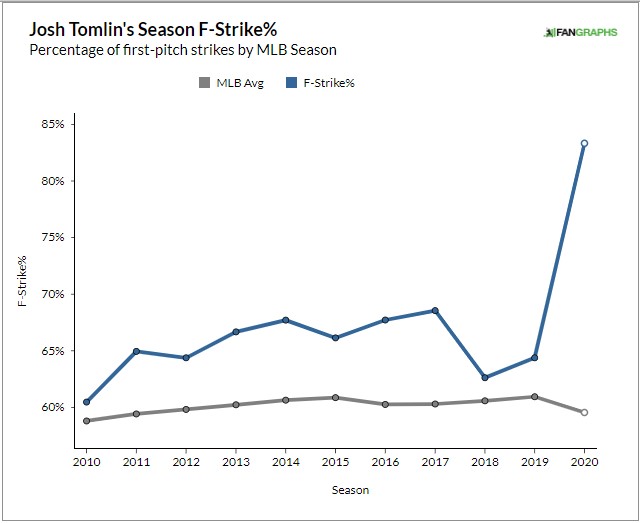

Now that we’ve looked at the pitches individually, the next thing to check up on is his approach, and that’s where the good stuff begins. Tomlin has always been better than most as drawing first pitch strikes. Pitchers with mid-80s velocity thrive on overaggressive hitters swinging out of their shoes. Tomlin has taken it to a new level so far this year, jumping out ahead in the count to, uh, just about everyone:

Source: Fangraphs

Okay then! Just how good has Tomlin been at getting ahead? As of this writing, he’s faced 41 hitters and thrown a first pitch ball to just six of them. Of those six, only a single one has made it to a 2-0 count. And a 3-0 count? In this economy? Unheard of.

As you’d imagine, this is a pretty effective adjustment. The league wRC+ on 1-0 counts is 124. On 0-1 counts, the league wRC+ is 71. Hitters are swinging at the first pitch against Tomlin roughly 5% more often than they did last year, which accounts for some but clearly not all of this drastic shift. Independent of any other changes, Tomlin has essentially turned one out of every five batters he’s faced from Gleyber Torres into Elvis Andrus. It doesn’t take a lot of time with that adjustment to start racking up some new, interesting numbers.

Of course, that’s a super overly simplistic way of looking at things. Still, small shifts in a pitcher’s approach can sometimes snowball into bigger dividends. The advantage of being ahead 0-1 in the count is that the batter has one fewer opportunity to pass up on a pitch they don’t want to swing at, at least if it’s in or near the zone. Naturally, then, hitters are prone to overaggressiveness when down in the count. In 2020, the league swing rate on 1-0 pitches is 29%, while those pitches are in the zone 52% of the time. But at 0-1, they swing 46% of the time, even though the zone rate on those pitches falls to just 43%. Count leverage in action!

Tomlin is taking full advantage of this tendency. In thirty 0-1 counts this season, he’s drawn 11 swings despite only throwing nine of those pitches in the zone. More importantly, not a single one of those swings has resulted in a man on base. If the head shake at the end is any indication, Brett Gardner realizes this swing is a bad idea with the ball about 20 feet from the plate:

Here, he places an 0-1 cutter just far enough off the edge that an overeager Bo Bichette can’t do anything but tap it to the 3rd base side:

The thing is, those zone rates don’t change after the 0-1 pitch, either. After he gets that first pitch strike, Tomlin avoids the zone like the federal government avoids accountability, never running a zone rate above 50% except in 3-1 and 3-2 counts.

There’s only been one of the former this year, but his 12 full counts out of 41 batters faced raises a bit of an eyebrow. But it still may be a (positive) double-edged sword. In the past, Tomlin would generally play it safe when ahead in the count, throwing either the four-seamer or cutter nearly ¾ of the time as recently as last season. In 2020, he’s got a newfound confidence in the curveball as an out pitch, throwing it more than 40% of the time when he’s ahead of the count.

Most of those pitches are out of the zone, which will lead to its share of long counts. It hasn’t mattered, though, as he’s allowed only a single hit on 61 pitches thrown when ahead in the count. Tomlin is used to walking on thin margins. Even in relief, he still has the command to get away with more three ball counts than most would be comfortable with. The league-wide zone rate on 3-2 pitches is just 56.5%, but come crunch time, Tomlin has hit the zone on 9 of his 12 (75%) payoff pitches. Long counts are a tradeoff he’ll take if the benefits are what they seem to be so far.

In a word, the takeaway here is that Tomlin appears to be aggressively getting ahead early in the count, taking advantage of the fact that it’s usually to the hitter’s benefit to not bee too swing-happy on the first pitch. Then, once ahead in the count, he’s daring hitters to lay off the low curveball, which they’ve to this point been unable to do. A bold plan for a righty throwing eighty-poo!

A Different Kind Of Tunneling

It’s remarkable—and pleasing to this former right-handed soft-tosser—to see such a radical late-career shift immediately play dividends. But it would be naïve to thnk that first-pitch aggressiveness is the only factor pushing a once-fading 35-year old to new heights. I’m approaching 2000 words already here, so I’ll skip another deep dive for a quick overview of some of the other factors than might be in play.

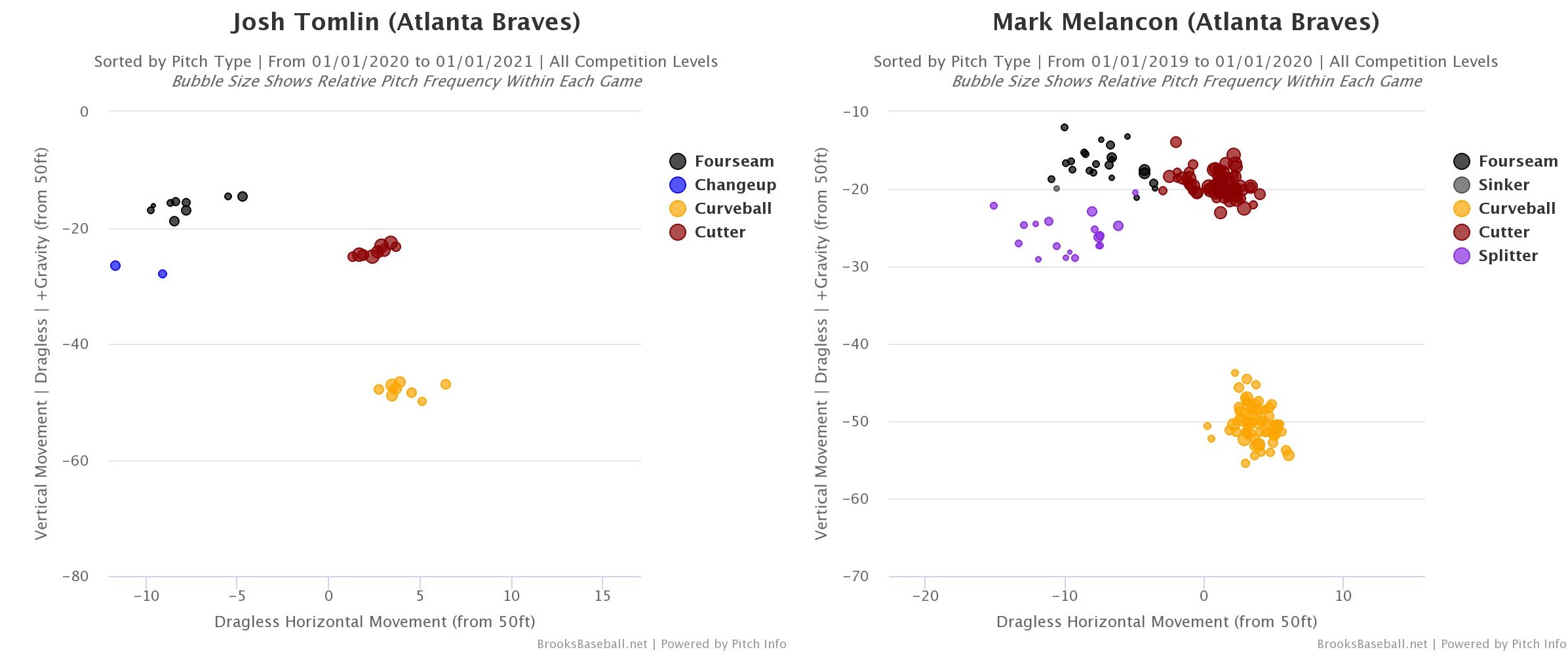

Tomlin’s new arsenal is a relatively unusual one, even for a reliever. Only two pitchers in 2019 threw at least 50% cutters and 30% curveballs, but Mark Melancon and Will Harris make for an intriguing pair of potential comps. Repertoires do not a similar pitcher make, but they can be instructive nonetheless.

One thing that stuck out about both Tomlin and Melancon is how well they mirror the two pitches. Most pitchers equipped with the cutter-curve combo have them with different degrees of horizontal movement; that is, the side-to-side usually varies by at least a few inches. But these two deploy their primary weapons on an almost perfectly vertical axis:

Source: Brooks Baseball

It’s debatable whether this kind of deception on such tiny margins actually makes the pitches more effective. As is the case with almost everything pitching, there are countless variables unique to each player that can change the calculus one way or another.

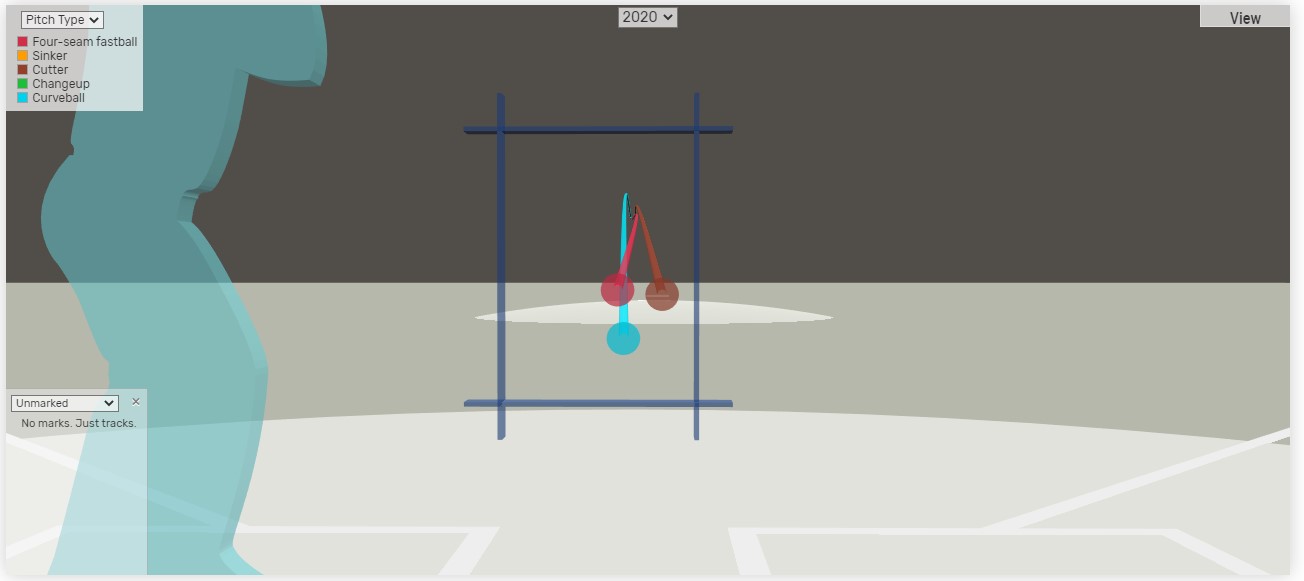

Still, it’s logical that having some strong similarities in terms of shape could make a particular pairing effective. After all, that’s the idea behind pairing a high-spin “rising” four-seamer with a vertical 12-6 curveball a la Justin Verlander. It’s harder to pick up on a pitch when you can only identify it in one plane rather than two. Baseball Savant’s 3D Pitch Visualizer can be a bit unwieldy as an analytical tool, but the shape of the cutter (brown) and curveball (turquoise) here look like they could be tough to differentiate were they to come from roughly the same release point:

It’s a different kind of pitch tunneling than what Baseball Prospectus measures, but it’s the same concept. And whatever it is, it’s working so far!

Tomlin is supposedly stretched out and prepared to go at least four innings when he makes his start tomorrow, and it’ll be fascinating to see how he utilizes his technically-still-four-pitch mix. The thing about two-pitch relievers is that they’re usually relievers because they’re two-pitch pitchers. Major league lineups often operate just like that old saying from Texas (and possibly Tennessee): fool me once, shame on you. Fool me tw—you can’t get fooled again! Slow stuff is slow stuff, and giving hitters more than one look at it could easily be a very dangerous proposition. But that’s the situation Atlanta finds themselves in right now. Even if Tomlin can’t translate his new weaponry back into the rotation, he may be in line for higher leverage innings come September than we ever would have imagined three weeks ago.

In conclusion: I like Josh Tomlin, and maybe you should too!

(Photo by Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire)

The “finesse righty who thrives on weak contact” is too similar to that dumb quote from Trouble With the Curve after someone (Jurrjens?) throws a no-hitter. I am triggerd