Part of me wanted to turn this article into an economics lesson. I wanted to talk about the history of commodity trading and individual markets. I wanted to talk about how some commodities’ markets fade away due to the times changing and compare that to baseball players. Then I tried to remember what the difference is between microeconomics and macroeconomics … and that was the end of that.

I suppose I’m in a good enough position to explore the market for Mike Trout in dynasty leagues. I don’t have an economics degree, but I’m in five dynasty leagues! One is in its 21st season, one is in its 15th season, and another in its 10th. Something odd happened within the last 12 months in each of these 10+ year leagues: Trout became available and/or traded for the first time.

This couldn’t be a coincidence. Up until 2018, Trout was absolutely untradeable. He is the best player of his generation. Trout’s career trajectory has him among the best players to ever play. He has accumulated more WAR than any other player at each age from 20-27. The only thing that threw him off that trajectory was COVID-19 shortening the 2020 season. He already has more WAR than more than 60 Hall of Famers. What does this have to do with dynasty leagues?

Obviously becoming Hall of Fame worthy by age 28 would suggest that you are quite the dynasty player to own. In fact, he has been the best dynasty player to own since his 2012 rookie season where he posted a .963 OPS with 30 homers and 49 stolen bases — at just 20 years old. He was so good at such a young age that opposing dynasty managers knew not even to ask about him in trade negotiations because there was no reason a manager would have to trade him. He was 22 when he won his first MVP, which means if you were in a dynasty league with a rebuilding team, even if things went bad, Trout would still be dominant by the time you turned it around — unless you are your league’s dynasty equivalent of the Mariners.

But I digress. The point is that Trout will turn 30 during this upcoming season, and enter the supposed twilight of his career. He is no longer the top dynasty player. In fact, he might not even be in the top three. And many managers who have enjoyed the fruits of his greatness for a decade have been starting to consider not if they should jump off the bandwagon but when, and for how much. That is the point of this article. If you own Trout, what you do with him in the next two years will define your next 5+ years. It’s time to look at how much longer Trout will be a big fish, and what the fish market smells like nowadays.

I want to point out that this isn’t a scientific study. I will quantify how much you should either offer for Trout in a dynasty league if you don’t own him or accept in a trade for Trout in a dynasty league if you do. Sure, I will point to other studies and make a few points about tertiary subjects that could affect Trout’s worth in the future or forecast what Trout’s career might look like as he succumbs to father time. Mostly, this article is the result of asking everyone who I have ever played in a dynasty league with, who I know who plays dynasty leagues, or who has asked me a question about their dynasty league if Trout has recently been traded in their league, and for how much. I didn’t ask anyone what they would theoretically accept or offer in a Trout deal because I’m not interested in dream scenarios. I want to know what the price tag for Trout has actually been. That is what we will be exploring today. But first:

Baseball Players and Their Primes

What do we know about the prime years of a baseball players career? Well, for starters, we know that it’s happening slightly earlier than it used to. We know that Major League Baseball players, on the whole, are getting younger, as Rob Arthur of FiveThirtyEight explains. There are two reasons why: Teams are skewing younger because younger players are cheaper, and we are in the middle of a historically talented youth movement. That also means that older players are being muscled out of starting job opportunities in favor of new blood. Thanks to Arthur, we also know that older players are beginning to fade earlier than they used to as well, although the reasons for that are not as clear. My uneducated guess has to do with performance-enhancing drugs. We just don’t see many players make an impact after age 35 as we did 25 years ago. And I don’t care how good you were in your prime, winning an MVP at 39 just isn’t natural — let alone at 37 and 38 too.

So when do players begin to regress? Most studies suggest somewhere between 29 and 31 years of age, which is basically what we all assume. The question we really want to know is: How much do they regress in that period? Craig Edwards of FanGraphs found as a group, MLB players lost at most 0.5 WAR per 600 PAs for every year older they were in 2017 after 30 years of age. Now, this was a study of the entire player pool for just one season. It did not look at how those same players performed in that year and how that related to the rest of their careers. For that, we can turn to Mitchel Lichtman in Hardball Times, who looked at the differences of players from one season to the next and cataloged the progression and regression of over 70 seasons. He found that players’ performance begins to fall at age 29 and that loss in production is enhanced every season thereafter until they can no longer play.

While each of these studies looks at a different aspect of the aging of baseball players, the conclusions all point to the same age — 30 — as being when the wheels start to fall off.

Mike Trout Isn’t Like Any Other Player

But there is one thing we also know about all of these studies: None of them include Trout’s stats at 30, 31, or 32 years old. We could easily say that Trout doesn’t fit the mold of most of these players. He’s not in just the top 1 percent, he’s in the top 1 of the top 1 percent of baseball players. Like I said earlier, he has literally broken the record for most WAR accumulated at every age he has played until COVID-19. So why should the end of his career look like the end of most major league players’ careers? It probably shouldn’t. So let’s look at a few players who are at least in the same stratosphere. Not just Hall of Famers, but the cream — of the cream — of the crop.

First, there are those with similar talent, but their bodies broke down. A lot of the center fielders who come close to Trout’s status saw injuries derail the twilight of their careers. Mickey Mantle and Ken Griffey Jr. are the notable comparisons here. They are two of the best five center fielders ever to play the game and they both dropped off dramatically after age 30 due to an array of health issues. Griffey was essentially a replacement-level player at best after 31 years of age, with the exception of a semi-healthy 2005, where he posted a 3.7 WAR. Mantle faired better, putting up mostly two and three WAR seasons after turning 31, with the exception of one last 1.000 OPS season at 34.

As good as Griffey and Mantle were, however, the more apt comparison for Trout is Willie Mays. A completely different story, the Say Hey Kid might have had his career’s best run from ages 31-34, leading the league in homers three of those years and winning an MVP at 34. One thing that was also amazing about Mays is he continued to play center field until he retired at 42. This is notable to consider from an injury standpoint, as center field requires more strain on the body than most positions on the diamond, potentially exposing the fielder to more opportunities to get injured. Although not a center fielder, another good comparison is Ricky Henderson. While he wasn’t stealing bases as he did early in his career, the Man of Steal had his best overall season at 31 years old and hit very well until 35. Now, both Mays and Henderson are statistical anomalies. They are once-in-every-two-generation athletes who were able to maintain their performance into their mid-30s and remain relevant into their late 30s. Henderson stole 66 bases at 39 years old while Mays posted a .907 OPS at 40. This begs a few questions:

Do generational players age differently?

There are two ways to look at this. The first is the Henderson way. He did age like an average player, but he was so good during his prime years that it took literally a decade for his regression to turn him into a replacement player. The other way is the Mays way, where he clearly did not regress until his mid-30s and even then he regressed at a rate that appears five years delayed as he regressed at 35 how a typical 30-year-0ld would. I think there is room to believe in both.

Will Trout stay healthy enough for us to find out?

It’s a little troubling that Trout hasn’t played 140 games in a season since 2016, although to be fair, he was on pace to do just that in 2020. Nevertheless, he was on pace to do it in seasons 2017-2019 until he wasn’t. That said, Trout’s injuries that have kept him out of commission in both 2017 and 2019 (thumb/wrist) are not causes for further concern. It’s not like he’s having chronic hamstring trouble like Griffey or knee/back trouble like Mantle. His injuries are more of the fluke type than the chronic type. Something that could help Trout maintain his health, however, is to move off of center field in the next few years. This is a delicate situation, as nobody wants to tell the potential best player ever that he can’t field the position he’s always done, but if it’s to cement his legacy, and help the team win, Trout seems like the kind of personality to accept it.

Has Mike Trout Aged?

Trout’s hair isn’t even thinning.

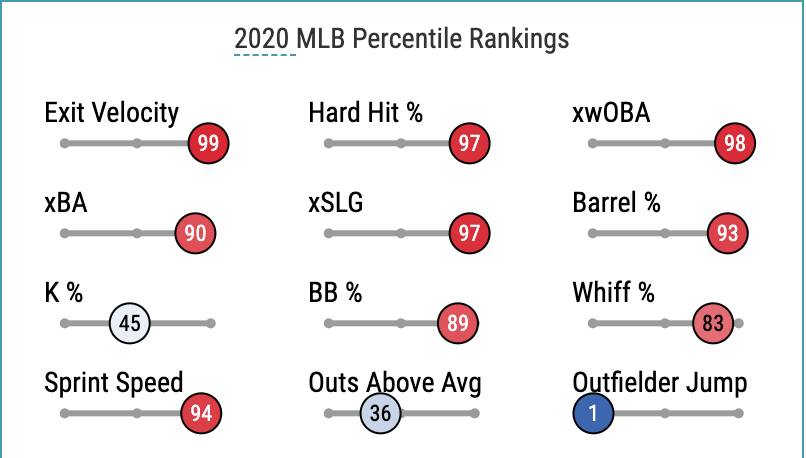

In fact, if we were to compare Trout’s career to his luscious hair, it would be even more luscious now than it was five or 10 years ago. There are no signs of aging. He doesn’t even have circles under his eyes, probably because every time he hits a dinger, he sleeps like a baby. Right now all I see is that Trout is actually continuing to get better. He’s swinging at fewer pitches outside the zone than he ever has (17.4% O-Swing). He’s making roughly the same amount of contact (82.4%) as he always has, and he’s extremely difficult to get caught swinging and missing (6.4%). This is troublesome to all pitchers because like Ivan Drago, whatever he hits, he destroys. Every time I see his contact numbers I am amazed. In 2020, Trout limited his soft contact to just 10 percent! You could double that mark and still be considered in good shape. Meanwhile, Trout’s exit velocity (93.7) is in the top 1% and his launch angle is a thing of beauty (23.1 degrees). Doesn’t matter if it’s XSLG, Hard Hit %, Barrell % — basically, if you ever want to know what a good Statcast number is in ANY hitting statistic, look at Mike Trout’s page.

He still uses all fields. He avoids ground balls. He’s among the league leaders in pitches per player appearance. The only quibble I have is that he is no longer walking as much as he’s striking out, but when you’re as good as Trout is, that doesn’t matter. That feat is also so difficult that it can come and go. It wouldn’t surprise me if the trend reversed and he did walk as much as he strikes out for the next few years.

The bottom line is, despite Trout hitting the traditional period when he’s supposed to decline, that just flat out hasn’t happened yet offensively.

So … What is Trout’s value?

I don’t know. But that’s not what we’re here for. The market for Trout is whatever someone is willing to pay in your league. Or, just as important, what someone is willing to give him up for. It also depends on what kind of league you are in. Obviously, if you are in a salaried dynasty league, his contract details will affect his value. You see, I can’t give you a definitive answer. What I can do, however, is show you some of the transactions he has been involved in and offer my opinion. So let’s do that!

Trade 1

Team A gets: Mike Trout, Andrew Heaney, Vidal Brujan

Team B gets: Cody Bellinger, James Paxton, Kris Bryant

This trade happened before the 2020 season started. I kind of like this deal. On the one hand, the only for-sure elite player is Trout. Bellinger has been elite for whole seasons at a time, but he’s also periodically fallen victim to contact issues. That said, this deal is essentially Trout for Bellinger. Paxton is, at this point, a lottery ticket, and so is Bryant, given how far his Statcast data has fallen in the past three years. As much as I like Brujan, there are a few of prospects with his profile who pop up every year or so. If you’re Team B, you’re hoping that Bellinger keeps pace with Trout for the next four years while he declines and then when Trout is 34, Bellinger will be 28 and entering the last few years of his prime. If you’re Team A, you’re hoping Trout ages like Henderson and plays better than Bellinger until he’s 35 while you try to win it all with the most consistent hitter in five generations leading your offense. This is not exactly a sell of to rebuild, which is why it’s different.

Trade 2

Team A gets: Mike Trout & Kenley Jansen

Team B gets: Luis Robert, Eloy Jimenez, Jesus Luzardo, Logan Gilbert, Jasson Dominguez

This trade happened in the last few months. Being a dynasty writer, the haul Team B gets for Trout makes me take a step back. The ceilings on each of the players Team B gets are in the top 25, except for Gilbert. That’s four potential top 25 players, three of whom are already enjoying muted success in the majors, for a legendary player who is about to turn 30. The difficulty is each of these young players has to overcome obstacles to reach those ceilings. Robert has swing-and-miss issues, to say the least. Jimenez is a power hitter who doesn’t walk, which will hinder his performance. In today’s analytics game, a .332 OBP is enough to drop you out of the top four spots in a lineup. Keep in mind, that was his OBP while hitting .296. Not a great sign. Luzardo’s early numbers are encouraging and suggest he will make a jump in 2021. That leaves with Dominguez, who has the potential to be a No. 1 prospect. I’d say Team B wins this trade, even without looking at the rosters. I mean, if all Team A needed was a center fielder to win, the manager could have held onto Robert. This trade isn’t for need in power or speed, because between Robert and Jimenez, there is plenty of both. Also, Luzardo is a solid piece. If Team B was trying to rebuild, it basically got enough to rebuild in two or three years off of this one deal.

Trade 3

Team A gets: Mike Trout, Gerrit Cole

Team B gets: Taylor Trammell, Kyle Tucker, Casey Mize, George Springer, 2nd-round pick

This trade looks close but tilted toward the team getting the two best players. As a rule, I do not accept a trade if I’m not getting one of the two best players. At the time of this deal in 2019, Tucker had yet to blow up and Mize looked like he was going to be dominant from the get-go. Two years later and I think Mize’s value is the same and Tucker has drastically increased his dynasty worth. By the end of 2021, Tucker could be a more impactful player than Cole. Springer is basically a shadow of Trout, but between him and Tucker, you can cobble together his impact. Or if Team B is rebuilding, it could flip Springer for more prospects/picks. I’m not a Trammell fan so that addition does nothing for me. I would have rather had another pick.

Trade 4

Team A gets: Mike Trout

Team B gets: Wander Franco, Luis Patiño, Ronny Mauricio, Noah Syndergaard

This deal happened in the same league as Trade 3, just a year later (2020). This is the kind of trade I thought I would see more of, to be honest. A Franco for Trout swap seems reasonable on its face. Franco is the most anticipated and highly rated prospect since Bryce Harper. Some say he’s the most highly rated prospect in the last 30 years. Along with Franco, Team B gets three lottery tickets. Patiño had mixed results in the majors, Mauricio’s stock has been tripped up and nobody knows what to think of Syndergaard anymore due to his inability to adapt and injuries. If I were Team B in this scenario, I’d be pretty happy. Between Trades 3 & 4, I sent Tucker/Mize/Springer/Trammell and a 2nd, received one season of Trout and got back Cole/Franco/Syndergaard/Patiño/Mauricio. The manager of Team B understands the art of good business is being a good middleman. Not bad.

Trade 5

Team A gets: Mike Trout, Kyle Wright, Chris Taylor, 1st-round pick (Bobby Witt Jr.)

Team B gets: Fernando Tatis Jr., Carlos Correa

This trade was completed in 2018. All-in-all, this is a pretty fair deal. Too often we view trades five years later in terms of how good the players were in the following years. That can make you think that the team trading for picks/prospects always wins. This example runs counter to that. Team A received a year of Trout in his prime before Tatis entered the league. The additions of Wright and Taylor are minimal, but the 1st round pick ended up being Witt. Correa was good for half a season in 2019, but has been injured for a lot of the aftermath of this deal. Essentially the trade is Trout and a 1st for Tatis. Not a bad deal a couple of years ago, and it holds up well today.

Trade 6

Team A gets: Mike Trout ($70), Kirby Yates ($8), Happ ($7)

Team B gets: Jared Kelenic ($2), Julio Urias ($13), Logan Gilbert ($3)

Obviously this league is a salary dynasty, which changes things. One could see this as a salary dump, but many view Kelenic as highly as the No. 2 prospect in all of baseball. This is a very good return if Team B had any concerns with its league’s salary cap. Gilbert is a solid pitching prospect and Urias will continue to be valuable.

Trade 7

Team A gets: Mike Trout ($49), German Marquez ($6)

Team B gets: Domingo Santana ($18), Dylan Cease ($5)

This 2020 trade, on the other hand, was an obvious salary dump. Unlike Trade 6, Team B gets almost nothing for Trout. Cease has value at a low dollar amount, but I’d rather have Marquez for a dollar more. I should also note that in this league, players sign contracts and Trout was in the last year of his contract. He’d have to be re-signed with a raise.

Trade 8

Team A gets: Mike Trout, Rhys Hoskins

Team B gets: MacKenzie Gore, Kumar Rocker, Riley Greene, 1st-round pick

This one happened just a month ago. There are a group of evaluators that would hate this deal: the TINSTAAP crowd. I’m not a member of this crowd. To devalue half of the prospects due to injury concerns only puts you at a disadvantage. If anything, it means you should double down on more pitching prospects, in my opinion, because every team always needs another pitcher because of all of those injuries. If you run lucky on the health of pitching prospects, you can trade for whoever you want when they start panning out. If you don’t, you’ll still be better off than most because you invested where they didn’t. That said, I wouldn’t complain about this deal either way. All the prospects have high ceilings, and there is a top pick involved.

Conclusion

As the offers above show, there are a number of ways you can trade Trout or trade for him. You don’t even really need to be all that creative anymore. I’m sure there are some dynasty managers who still consider him untouchable, and I don’t blame them. Not every team can have a top 5 dynasty player. And with the exception of perhaps Juan Soto, Trout is the most likely of the top five dynasty players to produce at the same high level every year for the next three to five years.

If you’re trading for Trout, consider him being an elite offensive force for four or five more seasons. Sure, he’s likely to start declining before he hits 35, but he is so good now that any kind of gradual decline will take years before he’s not a top 5 outfielder. There are just too many indicators that he’s playing at the top of his game.

Photo by John Cordes/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Redler (@relderntisuj on Twitter)