Boston’s arms are cooking.

Seriously, the Sox lead MLB in starting and relief pitching fWAR and have the lowest team ERA in the league, a ridiculous 2.08. Their plate discipline and batted-ball profiles are immaculate, so their expected statistics are more or less in line with actual results.

Wicked good.

This is almost inconceivable, considering Boston didn’t add many pitchers in the offseason. The one major acquisition, Lucas Giolito, blew out his arm before the season started.

This same staff was awful on the mound last season, but everyone has made considerable strides. Nobody expected much improvement, much less this drastic.

What happened?

The Group Chat

Outside of an unwillingness to spend, the big news in Back Bay this offseason was the new face in the front office. Despite rebuilding the farm system and ultimately doing everything ownership asked, Chaim Bloom was unceremoniously removed from the GM position. After a lengthy, somewhat embarrassing search, the Red Sox settled on Craig Breslow as the replacement. I actually came to like the hire, and I like it even more in hindsight.

The Red Sox never had a hitting problem. The lineup scored last year and will likely score again this season. Instead, Breslow is here to fix the pitching staff at the Major League level, something he did wondrously in Chicago. His first hire was Andrew Bailey, a former All-Star and Rookie of the Year. He came over from San Francisco, where he helped turn Logan Webb, Kevin Gausman, and Carlos Rodón into fellow All-Stars.

In turn, Breslow and Bailey ousted Dave Bush and hired Justin Willard as the new pitching coach. Willard comes from the Twins, where he helped coach up guys like Bailey Ober, Louie Varland, and Griffin Jax. Per Jen McCaffrey of The Athletic, Bailey, Willard, Jason Varitek, Dave Miller, and Devon Rose formed a text group aptly named the Run Prevention Unit. This coaching tree would turn everything around – or at least attempt to.

Per McCaffrey, the RPU spent hundreds of hours breaking down the profiles of all 22 pitchers and formulating detailed “plans” for them, figuring out how they wanted each pitcher to attack the art of pitching. The squad then hosted one to five Zoom calls per day with those arms, explaining their “plan” to them in detail.

What Is The RPU’s Plan?

So far, and from the general 30,000-foot view, it’s stop throwing your fastball. The Sox ranked second in baseball last season in fastball usage at 61%. This season, they’re dead last at 30%, five percentage points lower than the second-lowest team (Baltimore). They’re specifically not using four-seam fastballs.

Four seam fastball usage pic.twitter.com/MECZ2Toy9p

— Red Sox Stats (@redsoxstats) April 1, 2024

Instead, Boston has pivoted to cutters, sliders, and changeups.

But why?

In another excellent The Athletic piece by McCaffrey, Bailey is quoted as saying:

“The history of baseball suggests that fastballs in general have the most damage attached to them. So, looking at some fastball rates from last year, there’s some low-hanging fruit there and leveraging our weapons that generate weak contact and swing-and-miss more often.”

Additionally:

“Off-speed pitches generally reduce damage and generate more swing and miss. So every pitch we throw is a business decision. Every pitch we throw is a bet that we’re betting on decreasing damage and reducing contact. So most times, you want to leverage your best off-speed weapons, understanding that you know there is room to use your fastballs when needed.”

Fastballs get crushed. Off-speed pitches don’t while missing more bats.

What a novel thought.

It seems so simple and stupid, but Bailey is right. In 2023, hitters posted a .349 wOBA on four-seam fastballs, a .345 on sinkers, and a .337 on cutters. So far through 2024, a 5,700-pitch sample size, secondary pitches continue outperforming fastballs:

I’ve always thought you need a Major League fastball to pitch at this level, and you probably do. But if you have one, why lean on it so much? Everyone is hunting fastballs because that’s where hitters can do damage. It’s harder to park a changeup than a four-seam.

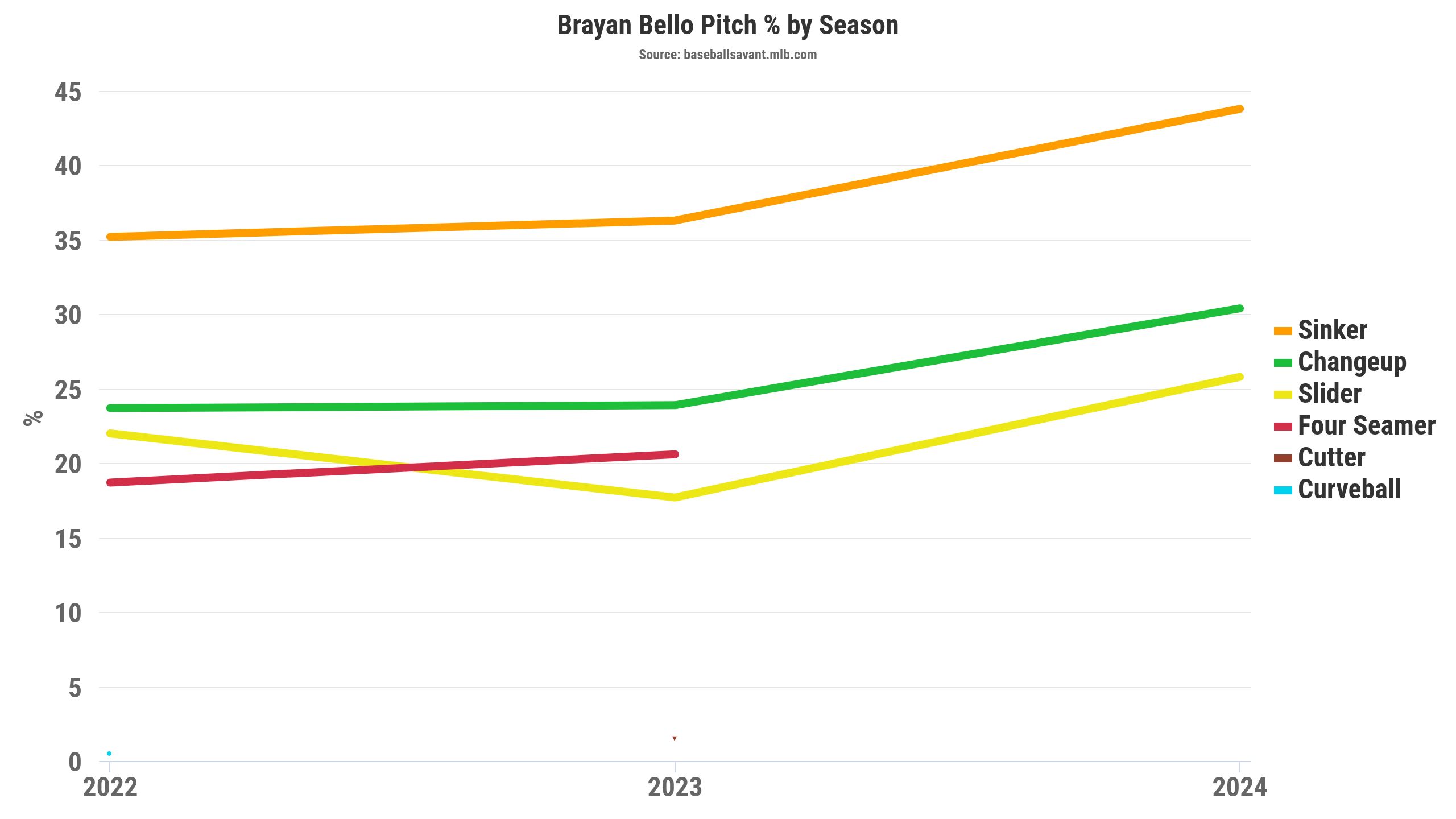

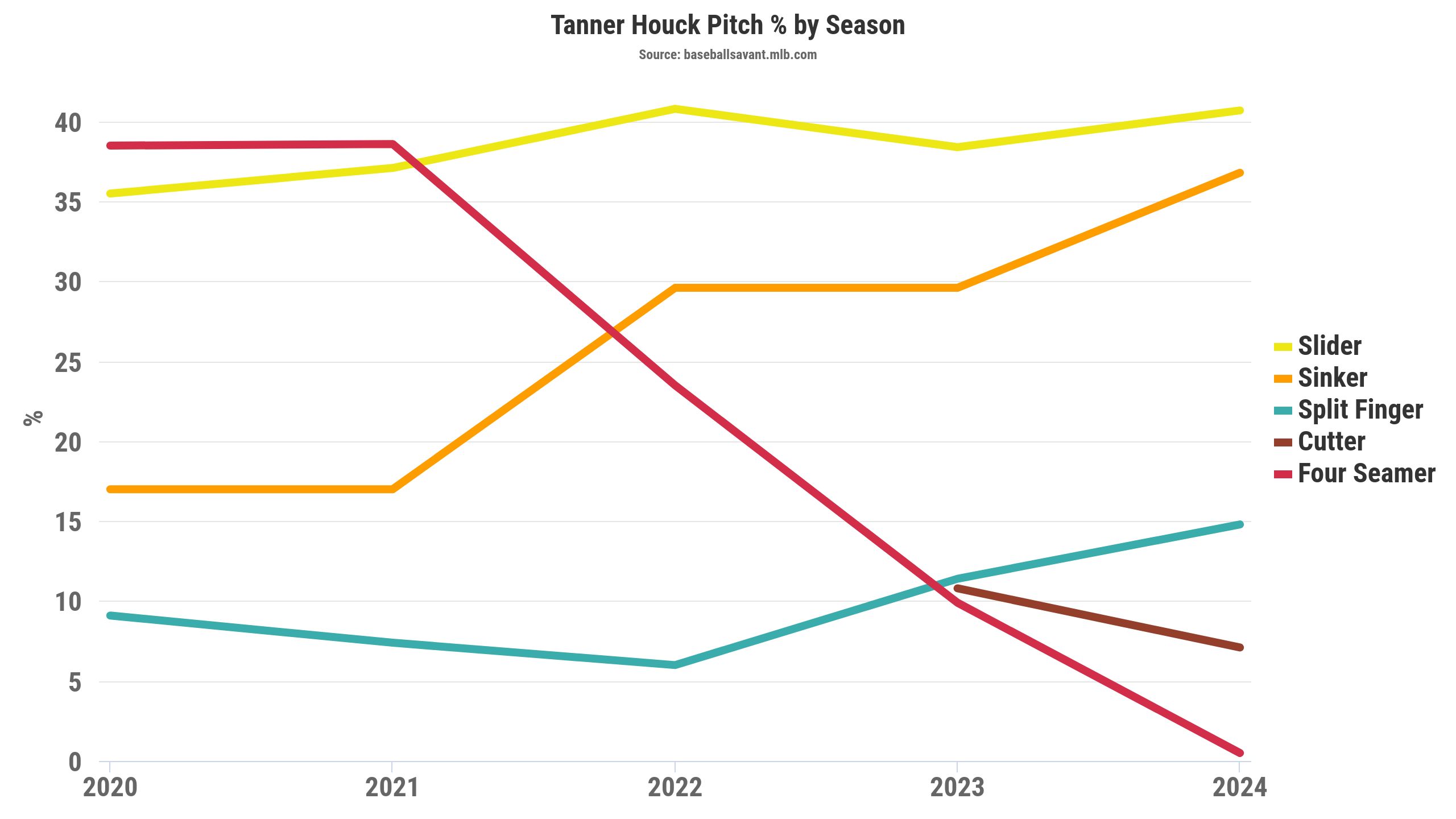

Let’s discuss this plan at a pitcher-specific level. We’ll start with Tanner Houck and Brayan Bello because their four-seam usage has dipped to precisely zero.

I read a tremendous article by Chris Gilligan of FanGraphs on this topic, who made a good point about how vulnerable low-velocity, low-stuff fastballs are. When they came in under 95 mph, four-seamers allowed a .371 wOBA, sinkers a .355 wOBA, and cutters a .339 wOBA.

“At these lower speeds, fastballs without much movement likely were not hard enough to overwhelm batters,” Gilligan writes. “As Bailey sees it, adding some cut or sink might help these relatively slower pitchers.”

Bello’s four-seam checked in at 95 mph last season but with an 83 Stuff+ mark. Houck’s four-seam couldn’t even hit 94 mph on average, and the Stuff+ mark on that was a below-average 95.

However, Bello has a nasty sinker-change mix, which he’s used to generate monster Whiff and ground-ball numbers during his early career.

Brayan Bello, Nasty 87mph Changeup. 👌 pic.twitter.com/OvW0WV16Wn

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) April 9, 2024

Houck’s slider is dirty; a sweeping glove-side pitch that reminds me of a mirror-imaged Chris Sale.

There are sliders. And then there's Tanner Houck's slider. pic.twitter.com/2oWjCzDWxV

— Red Sox (@RedSox) July 10, 2022

So, what do you think the RPU plan had in store for them?

For Bello:

The youngster has struggled a bit through his first three starts, but his xERA (3.74) is nearly a half-run lower than his ERA (4.11). The Stuff+ model grades his sinker (108) and slider (130) above-average. I think there’s positive regression for the kid as long as he continues to avoid the four-seam.

And for Houck:

The new-look Houck is beyond locked in. He struck out 10 A’s across six shutout innings in his season debut without throwing his four-seam and then followed that up with seven strikeouts across six shutout innings against the Angels. Both starts came on the road.

Not pretty, but efficient day for Tanner Houck nonetheless.

📈 Slider usage was up 13% (49% today/36% Mon vs Oakland).

SL was outlier, 5 whiffs (36% Whiff%), 15 swings (36% CSW%), 60% IZ-Contact%.

BTB starts successfully facing the lineup a third time.pic.twitter.com/xgpcITyWXi

— Pat (@PatSullivan05) April 7, 2024

While he will eventually allow an earned run, Houck’s xERA through these two starts is still under 2.00, primarily because he pairs a 38% strikeout rate with a 4% walk rate and a 64% ground-ball rate.

He grades out very highly by the Stuff+ model (114 across his arsenal), with his sinker (107), cutter (131), splitter (105), and slider (121) all coming in above average.

Houck’s four-seam was never going to be overly effective with its velocity and movement. Instead, he’s forcing ground balls with cutting/sinking action and whiffs with his slider. It’s a beautiful mix, all thanks to the RPU plan.

Tanner Houck, 94mph Two Seamer and 85mph Slider, Overlay. pic.twitter.com/tdUqTIj5Wo

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) April 7, 2024

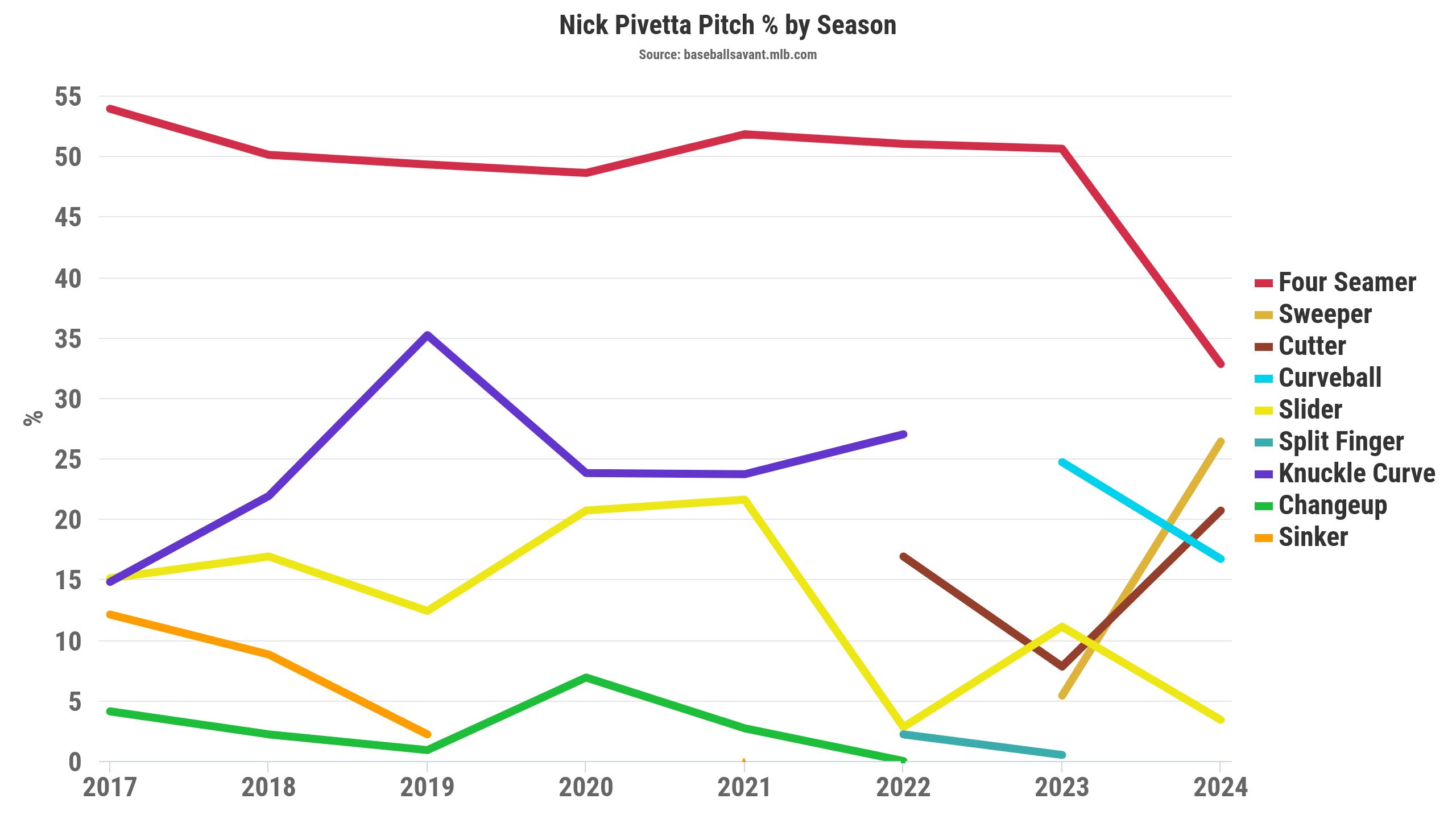

Let’s talk about a more intriguing pitcher, Nick Pivetta.

Pivetta is a fascinating case study of the RPU’s new-look system. He found something with his heater last year, and the ride on his four-seam this year is among the best in baseball.

I know it doesn't mean a lot to many of you, but Pivetta's fastballs in the 1st:

95 mph, 24.1" ivb

96 mph, 23.9" ivb

96 mph, 23.5" ivbTruly -insane- metrics (ride/carry) on his fastball.

— Red Sox Stats (@redsoxstats) March 30, 2024

While Bello and Houck shouldn’t use their heaters, Pivetta absolutely should. Thanks to the high velocity and crazy ride, he boasts a 134 Stuff+ mark and a 35% whiff rate on the four-seam. It’s cruising by batters.

However, he still significantly cut the use of the pitch.

Instead, he’s mixed in more cutters and a recently added sweeper, which redefined his pitch mix last year.

I conclude two things from the RPU’s Pivetta Plan. First, as mentioned above, breaking balls and off-speed pitches allow less damage and generate more whiffs. Second, perhaps more importantly, the RPU doesn’t want to ditch fastballs altogether but intends to deploy them more carefully. The increase in secondary stuff has significantly improved Boston’s fastballs. While they’re using them at a league-low rate, the Red Sox boast the highest Weighted Fastball Runs Above Average per 100 pitches (2.7).

McCaffrey quoted Bailey in her excellent piece as saying:

“We speak a lot about the fastball in general being a jab and equating that to boxing. If you’re going 12 rounds or eight rounds, you’re not going to win by throwing jabs the whole time. The damage is done by throwing your haymakers in your best sequences. Jabs need to be located supremely to do any damage.”

Pivetta is that theory personified. He has an elite fastball, but throwing it too much won’t equate to elite results, especially when the league smashes fastballs.

A bunch of this is sequencing. As Bailey tells McCaffrey, “I think the history of baseball suggests that when you’re in disadvantaged counts, your best strike pitch is a fastball from an ability standpoint, and I don’t think that’s true.”

The RPU plan is about being thoughtful and structured. In the past, the Red Sox would fall behind in counts and try to mash the zone with average fastballs, and they got obliterated in the zone. Boston is making an administrative, top-down effort to differentiate its thought process and pitch mix – more than any other MLB pitching staff.

“It gives you a little bit more of a concrete plan,” Pivetta told McCaffrey. “Bailey gives you the right amount of information, and it’s very structured about how they give it to you so you’re not getting bogged down by everything because that can get overwhelming as a player.”

Every pitcher has bought into their new-look plan, with variations across the staff.

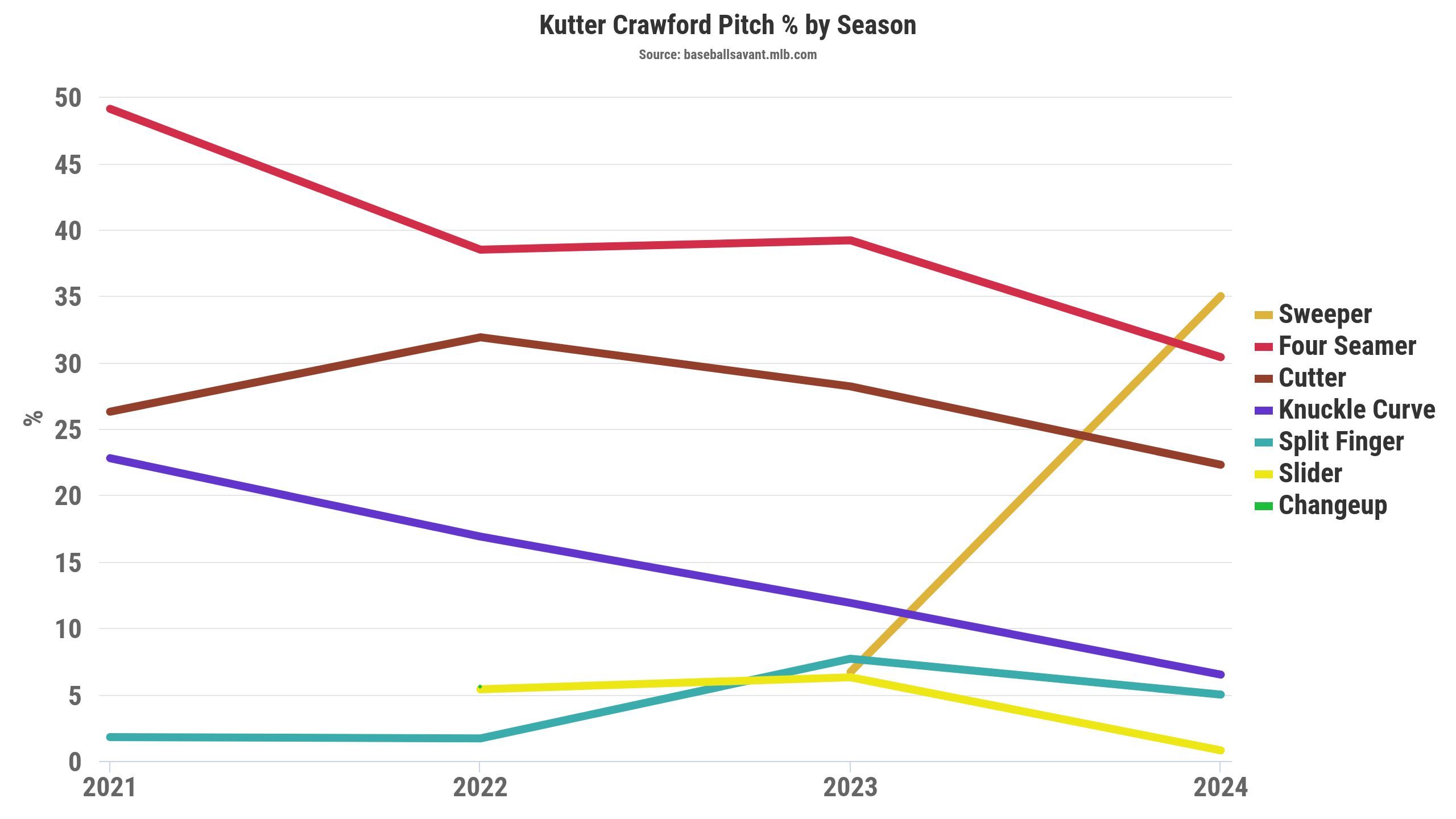

Aside from Pivetta, Kutter Crawford has the best four-seam on the staff. So, he’s continuing to utilize it as one of his primary offerings.

But he’s significantly increased the usage of his sweeper, which is generating a 30% Whiff rate.

Garrett Whitlock has never been a four-seam guy, but he entirely ditched the pitch while adding a cutter to pair with his beloved sinker. He’s also throwing more changeups, sweepers, and sliders, as you can see in this beautiful inning:

Garrett Whitlock, K'ing the Side in the 1st. pic.twitter.com/Os60qnjTyU

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) March 31, 2024

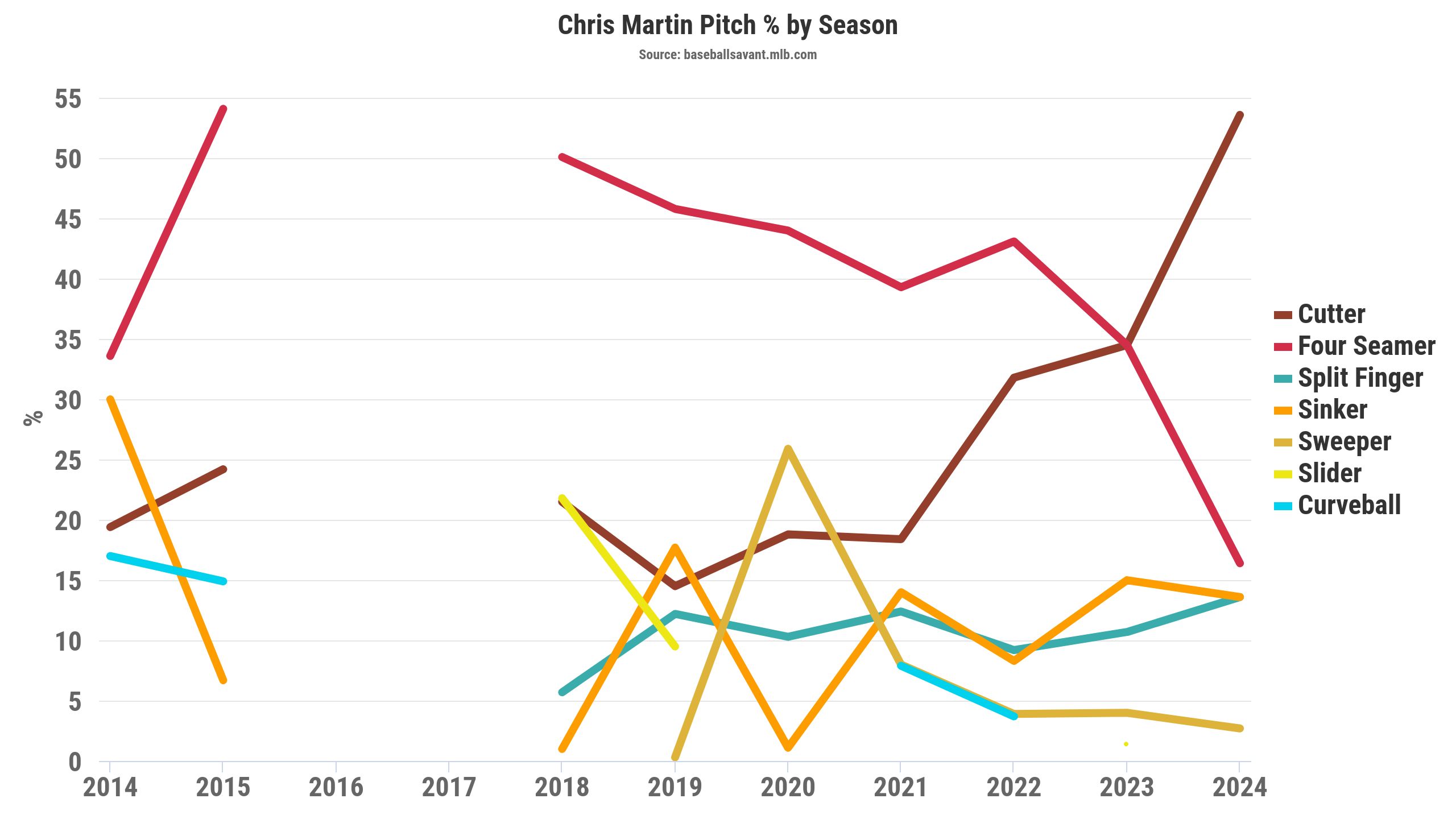

Reliever Chris Martin has long been a heavy four-seam fastball user, but the pitch allowed a .373 wOBA last year. This year, the RPU plan detailed a cutter-heavy approach with a slightly different sinker/splitter mix.

His ERA is juiced from a blowup appearance against Baltimore on Wednesday, but Martin’s cutter has always been excellent at inducing weak contact. As a result, he’s on pace to post a career-best batted-ball profile (24% hard-hit rate, 83 mph average exit velocity).

How’s It Going?

In short, it’s tremendous!

I mentioned the Red Sox lead MLB in several pitching metrics, but let’s investigate the underlying profile.

From a batted-ball perspective, almost nobody has been better. The Sox rank second in average exit velocity allowed (87 mph), seventh in barrel rate allowed (6%), ninth in hard-hit rate allowed (36%), and fourth in weak contact generated (6%). Therefore, they’re tops in xwOBA allowed (.286) and sixth in xwOBACON (.354) allowed.

It turns out that deploying off-speed and breaking stuff more often induces more weak contact. What a novel thought. However, using fewer fastballs in smarter spots has led to better batted-ball results on heaters. Boston has the lowest xwOBA (.233) and OPS (.322) allowed on four-seam fastballs. The Red Sox also allow the fifth-lowest line drive rate (20%) on the pitch.

From a plate discipline perspective, Boston’s pitchers have been missing bats left and right. The Red Sox pitchers force MLB’s fourth-highest whiff rate (28%) while recording the second-highest strikeout rate (28%).

Meanwhile, the Sox’s limited fastball usage has led to more Ks, as no team has a higher strikeout rate on four-seam fastballs (37%).

Also, I’m pleasantly surprised that the Sox aren’t walking anyone, with their seven percent walk rate ranking fifth among MLB teams. You’d think throwing more secondary stuff would lead to a lower zone rate, more balls, and more walks. Somehow, that’s not the case.

These results are not small sample-size luck. The Red Sox are throwing less fastballs, and it’s working.

What Next?

With Trevor Story going down for the year, the pitching better be good. The Sox have zero middle infield depth.

At least we’ll always have this start from Tyler O’Neill.

Tyler O'Neill is absolutely locked in.

Entered today hitting .357/.514/.893 (!!) and just launched his league-leading 6th HR! pic.twitter.com/S6xNTH53J0

— Brendan Tuma (@toomuchtuma) April 9, 2024

Look, the baseball season is long. The Sox opened their season with a road trip to Seattle, Oakland, and Anaheim – not exactly a gauntlet of elite offenses.

And as soon as they returned to hitter’s paradise, Fenway Park, they allowed 14 runs over 18 innings to the ever-dangerous Orioles. We are far from considering Boston an elite staff, and Pivetta’s recent IL stint is scary.

Still, this is really encouraging stuff. Perhaps more importantly, it looks like an innovative, top-down, analytically inclined structured approach for a staff that consistently underperformed under the Bloom-Bush regime.

It’s essential to have an aligned administration with a clear direction, plan, and goal. Boston now has that, and I can only assume it will lead to better results than last year’s debacle, even if the Red Sox aren’t on top of every statistical pitching leaderboard by October.

McCaffrey quoted manager Alex Cora in her excellent article saying:

“Everybody talks about throwing strikes, but we went from one philosophy to another in three years, and I think, with all due respect to the people that were running things, Chaim (Bloom) and the group, sometimes you got to be more consistent in that aspect. There were reasons for it and we tried our best, but it didn’t work out. We got hit hard in the zone last year.”

Really interesting. I hope you’re right … but of course, small sample size caveats apply. Looking forward to Nick’s wrapup tomorrow after the Angels were not fooled at all on their second look at Houck.

Thanks for the read! I doubt they’ll continue on this torrid pace, but I do think the structured analytically-inclined plan that everyone has bought into will produce better results than the last few grossly embarrassing years.